Underwater, by Cristina Coral, from her This Living Hands series (2012-2020).

Nymphs are a class of being that too many people today imagine as mere decoration (because they are often depicted this way visually), or, worse — as prizes to be snatched by the sexual predators of the ancient world, which included men, satyrs, and gods.

One of the more tasteful “nymph” photographs that comes up if you remove “safe search” settings. Here she is, all alone and not bothering anyone. What do you think page visitors imagine happens next? Certainly, a superficial reading of Ovid’s Metamorphoses gives the impression that nature spirits’ raisons d'être are less interesting than vicarious enjoyment of what intruding males want from them.

A little water nymph taxonomy

The category of nymphs is a catch-all for female-gendered spirits that are indwelling (both “in it” and “of it”) particular features of landscapes, particularly those that humans interact with using a light touch: for example, various natural formations of land and water, groves, wells and springs, etc. They are often associated with the vital health and creative power of the land.

Diego Rivera, Subterranean Forces (1927). Located in the chapel at the National School of Agriculture in Mexico City. This mural effuses a very different sort of wonder and respect.

The term nymph used in classical Greek and Roman myths, and is sometimes borrowed for analysis of myths from other cultures that talk of similar beings. Naturally, there is considerable overlap with elves, fae spirits, wights, etc., and sometimes newer, Christian layers of names and interpretations that reframed them as fallen angels, “devils,” and saints.1

Imaginary Gardens, by Sarah Jarrett.

There are many subcategories, and sub-sub categories of nymphs: some belonged to the retinues of gods and goddesses (for example, the huntress nymphs that accompanied Diana; Dionysus’ Maenads; and Hekate’s Lampades [torchbearers]). Among those who lived independently, some prominent types were mountain nymphs, tree nymphs, and water nymphs, which can be further divided into river nymphs (potameides, epipotamides), ocean nymphs, which I will discuss below, nymphs associated with springs (naiads, pegai, krenai), and those who inhabit marshes (limnaie, limonides, heleionomoi).

The term “naiad,” which often refers generically to water nymphs (derived from the Greek verb nab, "flow"), was synonymous with hydriad. Naiads were often considered to be daughters of river gods (which made them nieces of the Oceanids, whom I will describe below). And they were very numerous: a single river could have dozens or even hundreds of naiads keeping their father company in every feeder stream, current, and curve in his larger river.

Gaston Bussiere, Ninfe del mare ad una grotta (1924).

These nymphs also had personal names: in Greek mythology, many of their names contain the root -rhoe (e.g., Kallirhoe, "lovely flowing"; Okyrhoe, "swift flowing"). However, even those whose names do not include this root may be derived from other Indo-European forms with similar meanings: e.g., Peirene, Salmakis, Neda, Gargaphia, and Arethousa. Source. See here for more detailed classifications.

Ocean nymphs were very numerous, and were usually considered kindly disposed toward people.

There are 30002 graceful-ankled Oceanids; widely-scattered they haunt the earth and the depths of the waters everywhere alike, shining goddess-children.

And there are as many again of the Rivers that flow with splashing sound,

offspring of Oceanus that Lady Tethys bore.

It is hard for mortal man to tell the names of them all,

but each of them are known to the peoples who live near them.

- Hesiod, Theogony, 8th century BCE

Fresco depicting a Nereid half-reclining on the back of a seahorse. Location: a fast-food shop in Pompeii (early 1st c. CE).

Where nymphs dwell unbothered, all is well. This is why they have figured in idyllic imagery in art and literature since Classical times. For instance, in Sappho’s “Garden of the Nymphs”

“All around through the apple boughs in blossom

Murmur cool the breezes of early summer,

And from leaves that quiver above me gently

Slumber is shaken;Glades of poppies swoon in the drowsy languor,

Dreaming roses bend, and the oleanders

Bask and nod to drone of bees in the silent

Fervor of noontide;Myrtle coverts hedging the open vista,

Dear to nightly frolic of Nymph and Satyr,

Yield a mossy bed for the brown and weary

Limbs of the shepherd.”

Water nymphs as sources of law

More people are probably familiar with the Arthurian tale of the Lady of the Lake giving King Arthur a Sword3 — or at least Monty Python’s parody of it4 — than they are with the mythic origins of Roman law and state religion.5

Aubrey Beardsley, The Lady of the Lake Telleth Arthur of the Sword Excalibur (1893-4). Line block illustration from Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory, published by J.M. Dent & Co.

In my article about the Nemoralia, an annual festival held in August for the goddess Diana’s birthday, I briefly mentioned the nymph Egeria who had a shrine at Nemi behind Diana’s temple. Egeria (alternately, Aegeria) was the name of a spring that was eponymous with a naiad who had been known to inhabit the place long before Diana’s cult was established there.

The wise naiad was also said to be the consort of Numa Pompilius, the second legendary king who reigned after Romulus around 700 BCE.6 She mediated between the king, who was famed for his peaceful vision for his wisdom, and the other indwelling spirits of the local geographical area. King Numa showed his devotion with frequent visits to Egeria’s spring and grotto, seeking the nymph’s counsel on how to establish institutions that would duly respect the numena7 of the land.

According to myth, Numa established many of Rome’s key religious institutions, including the Vestal Virgins, the cults of Juipter, Mars, and the deified Romulus, as well as the office of pontifex maximus. (In reality, these institutions developed over a much longer period.) However, it would not be too far of stretch to say that the relationship of the naiad and the king represents a Roman version of a Sovereignty goddess with a mortal monarch who courted her favors and promised to serve her visions faithfully. While Egeria was not the source of Numa’s right to rule Rome, she did provide him with legitimacy that persuaded those who were not impressed with brute force.

A wood engraving from 1880 that depicts Numa Pompilius receiving instruction from Egeria on establishing religious institutions.8 Here is a gallery with more illustrations of similar scenes.

After Numa died of old age, it is said Egeria was so heartbroken that she abandoned her Roman spring and went to reside in Diana’s grove at Lake Nemi, where she wept so much that the goddess turned her into a spring there.9

Claude Lorraine, Egeria weeps over Numa (1669).

Hold up a minute — what Roman spring did Egeria abandon? Didn’t she originally hail from Nemi?

One of the things we can learn from these stories is nymphs were valuable elements of origin stories, and, while this back-dating may sound bass-ackward, they could be transferred from one place to another if someone wished it.

Thus, Egeria was said to have moved from Rome to Aricia instead of from Aricia to Rome. Thalia Took remarks: “Of course the Romans had it backward … but then the Romans were happy to co-opt any legend that could be used to glorify their early history, for example by claiming that their religious practices came straight from the gods. Aegeria may very well have been a Sabine goddess as much as she was a Latin one — Numa in the legends represents the Sabine faction of early Rome, and, according to Varro … Diana was of Sabine origin too.”

Thus, after the victory of the Latins, Egeria, or, rather, a branch of her cult was transferred to Rome. There, she was assimilated to the Camenae (water nymphs who protected sacred wells and springs, and had influence in the areas of childbirth, poetry, and prophecy).

As you can see above, the Camenae had quite an elegant facility built in their honor outside the Porta Capena in Rome. Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the Temple of the Camenae, from Views of Rome (1773).

We also see a similar process of appropriation or assimilation in the myths of another spirit of the place named Virbius. This fellow was originally a native Latin woodland god who had been associated with Egeria and Diana at Aricia since time immemorial. But in later retellings, from the Hellenistic period onward, he was made into a Greek — which sounded more noble and glamorous — named Hippolytus. Hippolytus, of course, was a character who already had his own story: tragically, he was killed by a curse uttered by Theseus that caused him to be trampled to death by Poseidon’s horses, and he was restored to life by Asclepius. However, bringing mortals back to life was against the divine order — and Asclepius had done this several times, which greatly angered Zeus. Artemis took the fugitive revenant to the grove in Aricia — where, by custom, no horses were allowed to enter. She renamed him Virbius to disguise his identity and prevent Zeus from finding out. But Zeus did know what Asclepius had done, and killed the rogue physician with a lightning bolt. Read more here.

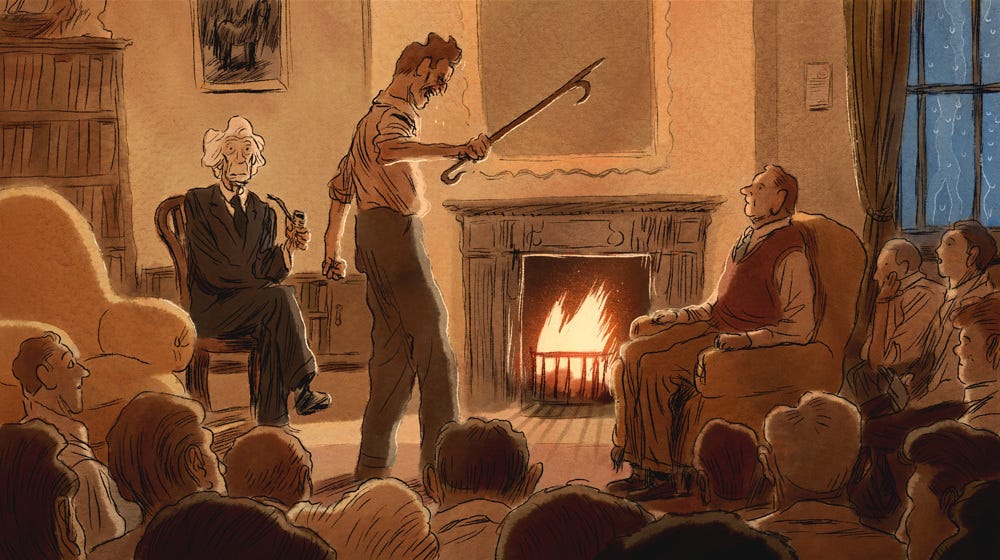

Virbius is credited with founding the great temple to Diana by the shore of Lake Nemi, and, by some accounts, he established the tradition of the Rex nemorensis so memorably described in J.G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough. I’ve written three articles that discuss the legacy of Nemi: below is a link to the one that focuses most directly on this aspect — and it spills some scalding hot tea on L. Wittgenstein as well! Why not have a read?

2. The king is dead - long live the King!

In my article “Nemoralia: the Ides of August,” I discussed the rites held at Diana’s sacred grove to celebrate her birthday and also spill some scalding hot tea on L. Wittgenstein.

Astronomical mirrors

When I asked about connections between inspiration, prophecy and water, my friend Kristin Mathis from Mysteria Mundi directed me to information about a monumental complex in Phoenician Motya (located on San Pantaleo Island - Western Sicily). The site underwent various stages of development, but ca 550–397 BCE it boasted of sacred pool, which connected the heavenly and watery realms. On the site were temples for Ba'al and Astarte, architectural niches, stelae, and other features orientated towards rising and setting stars and constellations, enabling synchronization with equinoxes, solstices, and other astronomical events. There is also a building on the western side of the complex that architects dubbed the “Sanctuary of the Holy Waters” on account of the cultic and hydraulic installations found within. I do not know which water deities or spirits may have been involved in the rituals and observances held at this remarkable site, but it seems likely that the connection between stars and the spirits in reflecting pools would be of great antiquity. And again, as with King Numa and Egeria, we see nymphs as a kind of subtle structure underlying a great edifice of the state’s religion and politics.

Nymphs as givers of ecstasy, inspiration, prophecy, healing — and death

However, nymphs always retained a wily aspect that couldn’t be fully assimilated to the formal realms of courts and temples. Water nymphs’ wet fingers were on the pulse of deep secrets of health and sickness; madness and epiphany; and life and death. In ancient Greece and Rome, water spirits could offer inspiration and divine revelations, or also — sometimes — a kind of ecstatic possession or frenzy.

In Greek, "nympholepsy" could mean being physically abducted by nymphs — we will see this in the myth of Hylas, which I will discuss below. By extension, it could also function as a euphemism or metaphor for death, as evidenced by Greek and Roman epitaphs.

Alternately, nympholepsy referred to "a heightening of awareness and elevated verbal skills" caused by the nymphs’ influence, or gifts of poetic or oracular eloquence. Those blessed by this experience had knowledge of all realms and spoke with ferocity and terror and devastating artfulness.

Members of Orphic and Dionysian cults often sought out such experiences — for water nymphs were said to reveal the secrets of Dionysus and Persephone to devotees. Those who followed the nymphs could be called a "nympholept” (Latin equivalent = lymphatici) and soothsayers or priests of this persuasion were sometimes called numphogêptoi.

A Bacchante, by Arthur Wardle, (1911 — reproduction). Attribution.

Often, the nymphs’ powers were associated with the particular waters they dwelled in. Hippocrene was a spring on Mount Helicon that was sacred to the Muses. Its name can be literally translated as “Steed’s Fountain” because it was formed when Pegasus struck his hoof into the ground, and its water was famed for bringing poetic inspiration.

Here is how Ovid describes Minerva’s visit to the site:

Fame has given to me

the knowledge of a new-made fountain—gift

of Pegasus, that fleet steed, from the blood

of dread Medusa sprung—it opened when

his hard hoof struck the ground.—It is the cause

that brought me.—For my longing to have seen

this fount, miraculous and wonderful,

grows not the less in that myself did see

the swift steed, nascent from maternal blood.

Minerva praises the Muses, and royally allows them to carry on at the site, which she deems suits them well. Since Minerva had ambitions of being known as a patroness of the arts, it is an act not just of condescension but also — somewhat — of appropriation. But - as those who have read my articles on Medusa know - Minerva/Athena kind of specialized in such acts.

Minerva’s Visit to the Muses by Joos de Momper the Younger (late 16th/early 17th c.) depicts the scene from the Metamorphoses where Minerva visits the Muses on Mt. Helicon to listen to their song and see the Hippocrene. Pegasus seems to still be stomping his favorite ground.

Nymphs and death

Hylas was a youth who served Heracles as his arms-bearer (and was also his lover). Heracles had brought his companion along with him on the Argo’s voyage — so he was considered one of the Argonauts. When Hylas went to the spring of Pegae in Mysia to fetch water, its naiads fell in love with him. In the painting above, you can see one of them creeping up on the unsuspecting young man. He gave out a cry as he was pulled down into the water that was heard by the others. Heracles, greatly, distressed, searched for his friend for a long time, but the Argonauts eventually had to continue on their quest without him. Afterward, in memory of Heracles’ threat to ravage the land if Hylas was not found, the inhabitants of Cios each year on a stated day roamed the mountains, shouting aloud for Hylas.

A Naiad, or Hylas with a Nymph, by John William Waterhouse (1893).

What happened to the youth? Apollonios Rhodios tells us “a nymph lost her heart to him and made him her husband,” but Valerius Flaccus’s Argonautica offers a more polyamorous version: the men never found Hylas because he had fallen in love with the nymphs and remained "to share their power and their love." I guess Heracles couldn’t compete with that!

Another take on the motif — relating to the more communal love story — painted by the same artist is shown above in Hylas and the Nymphs (1896). This painting, and the one beneath it show a more seductive and less predatory imagining of the scene than the first painting. For more on Waterhouse’s paintings and his preoccupation with passages to deathly realms see my article “The White Deer As Memento Mori.”

All three of the images of Hylas I’m sharing, including the one below, can be interpreted so that the nymphs leading the fair youth away functions as a metaphor for death. Art historian Meaghan Kelly writes, “The nymphs, bathed in light stand out, while the figure of Hylas almost blends into the background patches of color. The bodies of the nymphs, vibrant and alive contrast the darker figure of Hylas, perhaps suggesting his impending death.”

This version of Hylas and the Water Nymphs (above) was painted by Henrietta Rae (1910). Her handsome model looks slightly reluctant to enter the water, but willing to be persuaded.

Unsurprisingly, especially in the light of the association between nymphs and spirits that guide or welcome the dead, even the sought-after or subjectively positive effects of possession by nymphs were eventually overwritten by Christians to suit their doctrines that promised “victory” over death:

Promises to facilitate the union of souls with YHWH after death went hand in hand with the long process through which not only all competing deities were demonized, but indwelling land spirits were syncretized with fallen angels and with malevolent spirits that previous generations had considered a menace, such as Lamia and Gello. The early Christian apologist and polemicist Tertullian warned of “unclean spirits” that lurk in water sources, and later authors, such as Isidore, Bishop of Seville, took it even farther and classified nymph-induced ecstasies as mental or physical illness.

The Women of Amphissa, by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1887) illustrates solidarity cooperation between regular women, nympholepts (the tired revelers), and the nymphs (not pictured), but surely not considered “unclean” or demons by anyone present.10

Lilith — a lawless water spirit?

It makes all the sense in the world that spirits associated with water are involved with its legal and moral orders, because without everyone behaving as through they have a stake in the availability of clean water, survival is impossible. This theme will be explored more below in the section on well maidens. But before we get there, let’s take a detour into Lilith’s world.

Paul Lormier, Infernal Apparation (1848). Probably a costume design.

Yep — that Lilith. I’m sure my readers know there’s a lot of nonsense and woo written about Lilith, and misidentifications of the sources of her lore and of representations in art (e.g. the famous Burney Relief). Was she an evil spirit? A goddess? Something else? My own guess is that, like the Gorgons, she was a much older — Neolithic or earlier — divine being whose original roles included bringing lives into and out of the world.11 Her birdlike and snakelike attributes reflected an ability to move between heavenly, earthly, and chthonic realms, and her terrifying aspects reflected her role as a protector of mysteries

~ A tale as old as time — beauty and the beast!

However, civilized people who were devoted to new cults of sky and grain gods increasingly characterized Lilith as a demon and a threat to decent families, in the same way that they made Medusa into a monster. (I am simultaneously writing another essay on similarities between the stories of Perseus slaying Medusa and Gilgamesh and Enkidu killing Humbaba and other “monsters,” and have these themes very much on my mind.) It’s also possible that there was slippage between seeing a figure as a benevolent spirit who guided souls toward their next destination and a demonic one that killed them for its own evil purposes.

A Hebrew incantation bowl — intended to bring healing to the patron’s daughter — featuring a depiction of Lilith. Photo credit: Albert Hastings.12 These bowls were discovered in excavations of houses — nearly every household had one or more of them — as well as in cemeteries, where they probably helped to pacify the ghosts.

Lilith is perhaps best known from Jewish legends that represent her as Adam’s first wife, made from the same clay YHWH fashioned him from on the same day he was created. She was banished from the Garden of Eden because she was not subservient to Adam, and she was replaced with the — at least initially — more compliant Eve.

Adam, Eve & Lilith, by Pamela Penney (2016).

However, Lilith’s roots reach much deeper. The Sumerian word lilitu refers to a wind/storm spirit or a female demon, and there is the hlilu in Akkadian literature and the lili in Sumerian literature. The Sumerian King List (late 3rd millennium BCE) registers the father of Gilgamesh as a lilu, so these spirits were not yet utterly beyond the bounds of civilization. However, Gilgamesh was sent by the goddess Inanna (who ruled over the areas of love, war, and fertility).

Intriguingly, in an Assyrian Akkadian translation of part of the Epic of Gilgamesh dated to 600 BCE (much later than the earlier parts of the epic were recorded) a “spirit in the tree” called a ki-sikil-lil-la-ke is mentioned. Suggested translations for this spirit’s name include ki-sikil as "sacred place," lil as "spirit," and lil-la-ke as "water spirit".13

In Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld (2150-1400 BCE, predating the Epic tablets), there is a description of a halub (willow) tree. The goddess Inanna has it brought to her city of Uruk, and plants it in her garden, planning to have furniture made from it after it matures. However, a magical snake, bird, and demon-maid take up residence in the tree, so it cannot be harvested. Inanna’s brother, the sun god does not help, but Gilgamesh does: he kills the snake, drives away the lilitu and the bird, cuts down the tree so Inanna can have a chair and a bed, and fashions two magical items for himself — which may have been a war drum and drumstick. Further adventures ensue in which Gilgamesh journeys to the underworld and emerges serving a fresh batch of moral lessons for his people.

In later Hebrew texts, the term lilith or lilit (variously translated as "night creature," "night monster," "night hag," or "screech owl") first occurs in a list of animals and mythical creatures in Isaiah. By this point, she/they is definitely not the sort of being that becomes the mother of kings. Commentators and interpreters often describe Lilith as a dangerous demon of the night who is sexually wanton — with some of the lore describing her as a kind of succubus — and she steals babies.

The Hebrew culture reviled her, but she was known to the earlier Mesopotamian cultures as free and happy — according to the Assyriologist Wolfram von Soden, a merry, laughing goddess/demon with unclean, hairy, animal traits — yet she was still a sexual being.14

This is not Lilith — it’s a representation of the “Seven Deadly Sins” by Innocent III from De sacro altaris mysterio, Metten Abbey (1414–1415). Notice any similarities?

In general, water is considered a portal for all kinds of spirits in Judaism. One can find numerous (re)citations of this phrase: “To get in touch with her universe, Lilith used water as a portal” on pages created by Lilith’s admirers, but I have not been able to trace an origin for it. When I asked Sara Mastros, she told me: “a careful reading of Torah will reveal that nearly all prophetic visions occur within sound of running water; however Lilith in more modern lore is more closely associated with mirrors,” so I am not sure to what extent the association may be generic to many spirits or specific to her.

According to an anonymously-authored satire titled The Alphabet of Ben Sira (composed between the 8th and 11th centuries CE), after Lilith left Adam, he complained to YHWH, who sent angel messengers to spy on her. They reported back that they had seen her on the shores of the Red Sea, in a place populated by a particularly lascivious breed of demon. Her new lovers were fathering the hundred little demons she gave birth to every day, and she was preying on human fetuses and newborns. (And perhaps this illustrates what I suggested above: that there can be blurred lines between a spirit that takes souls away after they die for fateful reasons, and one that is predatory and “evil”. Look, for instance, at how sirens changed over time from psychopomps to predators.

This Lycian siren (or harpy) from the Harpy Tomb, circa 480 BCE, uncovered in Xanthus, Turkey is nursing the soul of an infant that just died. She is a compassionate psychopomp, not a monster.

In any case, what we can distil from this account is that Lilith had powerful associations with birth, death, and water. She defied the laws of men and YHWH and was a kind of untouchable law unto herself in the area of sexuality and reproduction, and she could be pacified but never vanquished.

Lilith, by Linda Garland. This contemporary artist is drawing on older representations of Lilith and Eve.

Lilith is, unsurprisingly, often depicted as the snake who tempted Eve to disobey YHWH in the garden by eating the forbidden fruit. In these envisionings, she is usually depicted as a woman from the waist up, and a snake from the waist down — just like the dragon (drakaina) Echidna, whom I discuss in my first article about Medusa, and other half-human/half-snake deities and spirits that I discuss in Medusa Part II.

The imagery associated with Lilith and the snake is also shared with the devil in some versions of the myth of Adam and Eve. For example, the apocryphal text Vita Adae et Evae (The Life of Adam and Eve) relates that after the pair were expelled from the Garden of Eden, they cried and moaned for seven days. They craved the angelic food they’d enjoyed in the Garden, and couldn’t decide whether the things they found outside were edible. Adam suggested that if they did a penance God might take them back: he would stay for 40 days in the River Jordan, and Eve would stay for 33 days in the Tigris. However, Eve’s “weakness” caused her to mess up again: after only 28 days had passed, Satan, disguised as an angel, tempted the woman a second time, telling her that God had already forgiven her.

Eve fell for his tricks again and got out of the water before her penance was done, which spoiled all of her and Adam’s efforts and ensured they could never return to Paradise. As mean kids used to say in the ‘80s: “Psych!” LOL.

Illustration from the Jean de Montauban Book of Hours, named by the Breton nobleman it was made for around 1430. See more here.

Lilith is a fascinating subject, but I don’t want to go take the discussion any further here.15 Let’s just wrap up this subsection by pointing out that these comparisons could be a fruitful area for further inquiry.

Nymphs as protectors of water

Nymphs’ powers were both inherent in themselves, and be derived from the springs they guarded — they are a personification of the idea of source.

Gustave Courbet, La Fonte (1862).

The key fact to keep in mind is that water is needed by all living beings, including farmers’ crops. Thus, the hydriads would be worshipped alongside Dionysus and Demeter, and they were given epithets such as karpotrophoi, aipolikai, nomiai, kourotrophoi, etc. And shepherds would be careful to avoid offending nymphs where their flocks grazed, and would apologize for damage such as branches broken from trees or their animals’ hooves muddying the water of pools and streams.

Celtic and Brythonic cultures had water goddesses (e.g. Danu, Sulis, Coventina), and they also had well maidens, who could be considered similar to some of the naiads. Some cases may have overlapped, such as the river goddess/goddess of fresh water Tamesis, whose name means “dark waters” and was given to the river now called Thames.

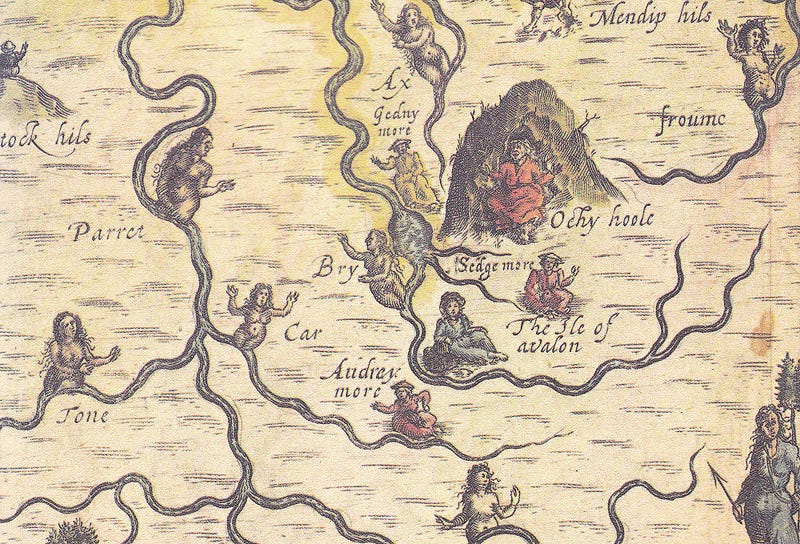

This illustration is a detail from a map of Somerset, taken from Drayton's Poly-Olbion; which was published in 1622. It shows us that as late as the early 17th Century, sacred waters were still personified as river nymphs. (Note that the River Brue is spelled “Bry” and the River Cary is spelled “Car.” The source for this image is a page created for a wide-ranging project called Well Maidens of the Summerlands, which was conceived by the late Bahli Mans-Morris, Casey Jon, Avia Willment, and Yuri Leitch.

In The White Deer, I describe the consequences when well maidens — who are representatives of the land’s sovereignty — are not protected. For example, the second part of the anonymously-authored Elucidation, which was composed as a prologue to Chrétien de Troyes’ Peredur, describes how the enchanting, fairy-like Maidens of the Wells, who guarded the holy waters, used to serve food and drinks to all visitors. Any pilgrim, knight, or other traveler could be treated to refreshment from their sacred springs until the wicked king Amangon, who was responsible for protecting them, betrayed them. He raped one of these maidens, and encouraged his men to follow his example with all the other well maidens — and they also stole their cups. Because of these heinous crimes, the land died and became the barren wasteland of the Grail stories. And the Castle of the Fisher King, which housed the Holy Grail, could not be found for a long time.

King Arthur’s knights were sent on a quest to find the Maidens of the Wells, and they ended up defending some other maidens, who turned out to be the descendants of the original Maidens of the Wells and their rapists. Eventually, the knights find the Fisher' King’s castle, but it is under an enchantment which cannot be lifted until the knights behold the Grail and ask the right question.

Depending on the version of the story, the question can be “Who does the grail serve?” In another story, “Who serves the grail?” And in a third, “What do you need?”

Arthur Rackham’s illustration of the Grail maiden from Alfred Pollard’s 1917 Romance of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, an abridgement for children of Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. The chalice shape of the Grail, and the myth that it was the drinking vessel Jesus used at the Last Supper were latter additions to its mythos.

Pious answers to the Grail questions involve service to God. More traditional answers probably involved the health of the land as a necessary condition for the flourishing of the people. As Leitch et al write, “Knights, rescuing and defending maidens, thus has a deeper and more profound meaning than simple romantic chivalry and gallantry. The actual quest was always to restore the land, and the knights, by giving service to the maidens that they encountered, were actively calling the divine feminine back to the land; so that the land could live and be fertile again.”

An interesting link between the ancient pagan stories and the later Christian ones is found in Perceval’s sister, usually identified as Lady Dindraine/Dindrane. This retelling by Jo-Anne Blanco of the Grail Heroine’s legend feeds right into later hagiographies where the unnatural deaths of water maidens provided origin stories for something useful and good (a healing spring, and the eventual ascendancy of the Christian faith) rather than a wrong that that had to be set right.

During the Grail Quest, Dindrane meets Galahad at a hermitage and persuades him to accompany her, providing a girdle for his sword made from her own hair. The two travel to the coast where they find a white ship with Percival and Bors waiting for them, whereupon Dindrane reveals that she is Percival’s sister by their father King Pellinore. The four sail away to another land where Dindrane instructs them to seek out the Maimed King and to find a cure for his mysterious wound that will not heal. They arrive at a castle where the castle knights demand that Dindrane give a bowl of her blood to the lady of the castle to satisfy their tradition. Dindrane refuses, and a battle ensues between the questers and the castle knights, in which the latter are vanquished. Accepting defeat, the castle knights make their peace and invite the visitors to stay at the castle.

Later that night, Dindrane and her companions discover that the lady of the castle is dying of leprosy and that only the blood of a pure virgin who is the daughter of a king can save her. Filled with pity and despite the great risk to herself, Dindrane agrees to offer her blood, a decision which proves to be fatal. During her bloodletting, knowing that she is about to die, Dindrane asks Percival to place her body in the white ship and set it out to sea. She tells him that he will find her in the city of Sarras and asks him to bury her there. Foreseeing that Percival and Galahad will die soon after her, she instructs the three knights to part company until they find each other again at the castle of the Maimed King. Galahad and Bors leave, and the grief-stricken Percival writes an account of the life and adventures of Dindrane, places it beside his sister’s body on the white ship, and sets it to sail out to sea. Later, the three knights travel to Sarras, where, after Galahad has achieved the Grail and healed the Maimed King, he and Percival both die and are buried beside Dindrane, the Heroine who ultimately demonstrated the true, selfless meaning of the Grail by sacrificing her life for another.

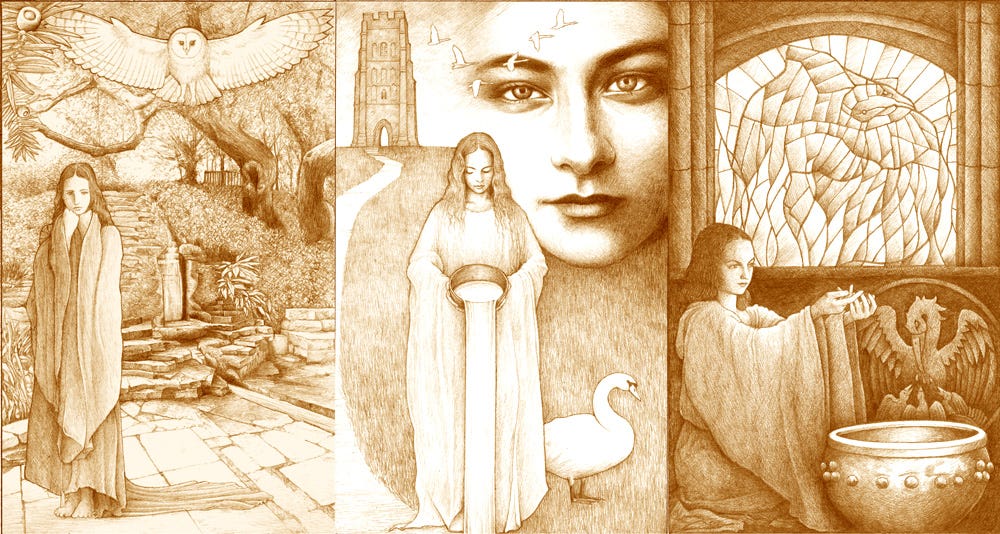

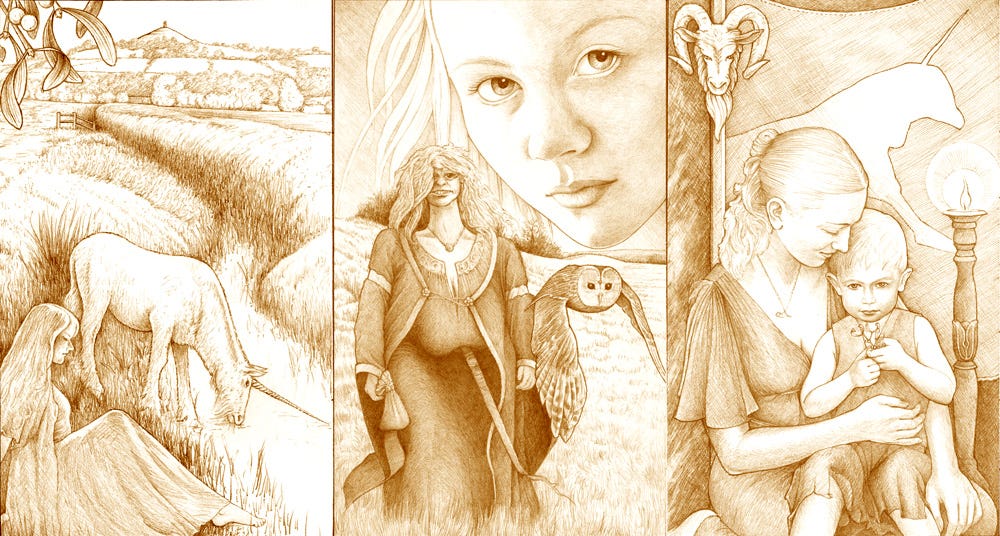

Triptych of Lady Dindraine depicting her as the well maiden at Chalice Well; at Glastonbury Tor; and sacrificing herself below a stained glass window of her effigy. By Yuri Leitch.

Some of the naiads and well maidens were so thoroughly assimilated into Christian hagiographies that we no longer know their original names. One of the prime examples of this is St. Winifred. We don’t know who she might have been before, but her hagiographers claim she was the daughter of families connected to both secular and religious authorities. When she refused the advances of a pagan suitor, Caradog, he chopped her head off. Winifred’s uncle restored her head to its rightful place, and a spring healing spring appeared, which has been called the “Lourdes of Wales.”

St. Winifred’s spring today. Photo credit.

I have no doubt that people were aware of the healing spring, and that it had a female attendant long before Winifred’s story was attached to it. However, something has been lost in the new retelling: while the older stories draw an explicit connection between the well-being (ha ha, punny!) of the maidens and of the land, the pious Christian martyr only “causes” the healing spring to pour forth after her violent mistreatment.

Martyrdom of Winefride, stained glass window in Shrewsbury Cathdral, by Margaret Agnes Rope (1910).

Another cephalophore martyr associated with water is the second-century martyr St. Quiteria de Caloocan. Quiteria was a nonuplet — one of nine sisters born together, which is a number of babies that is conspicuously a) unlikely for a human mother, and b) the same as the number of Greek Muses.16 According to the hagiographies, the nonuplets’ mother was appalled at having so many girls and no boys, and believed that having this many babies was “demonic” or animalistic. She was so ashamed of her “litter” that she first considered drowning them (another water theme!), but instead gave them all away to Christian foster parents. All nine sisters rebelled against their pagan father, became Christian renegades, and died for their faith. Three of the nonuplets were sainted, and the rest were considered honorable martyrs — the closest they could get to being translated into immortal beings in the new religion.

Quiteria, like Winifred, had rejected a suitor, with fateful consequences. The Virgin Mary promised her that her virginity would be preserved, and an angel set her free after her father imprisoned her for disobedience. As she fled, she begged the angel to find her some water, to which he replied: “Where you would like to drink, you will find a fountain that will never run out, and you will be blessed." This legend has another connection with water, because there are usually downpours on Quiteria’s feast day.

There are many versions of the story, but a common one says that the maiden was hunted down by her father’s men and beheaded. However, Quiteria was no quitter, and she carried her head to Aufragia, where she received a Christian burial. So, besides the regular rainstorms, her story is also used to explain the existence of the medicinal water called La Santa in the town of Mora de Santa. At the edge of the village is a garden said to be the place where the saint was martyred, next to a fountain that is considered to have curative powers against rabies — a disease once known as hydrophobia.

Quiteria’s sister Eumelia/Euphemia threw herself from a cliff, but instead of dying in a mundane, splattery way, a rock gaped open and swallowed her and a hot spring bubbled up right at the spot.

St. Quiteria’s cult thrives today in Spain, France, Portugal, the Philippine Islands, and even India.

More than human / less than human

Most water nymphs were not immortal — with a few exceptions such as the Oceanids and Nereids, who were goddesses. However, nymphs could live much longer than men and women and they had some magical powers. One of the differences between Christian and Pagan myths was the former seem to relish the sacrifice of female water protectors, while the latter often featured the diminishment of their powers.

Sometimes, nymphs lost their special status as semidivine beings after a rape, either because of the nymph’s own shame and humiliation, or as a punishment by a vengeful goddess (e.g. Juno). It could even happen in the course of a desperate effort to flee a pursuer.

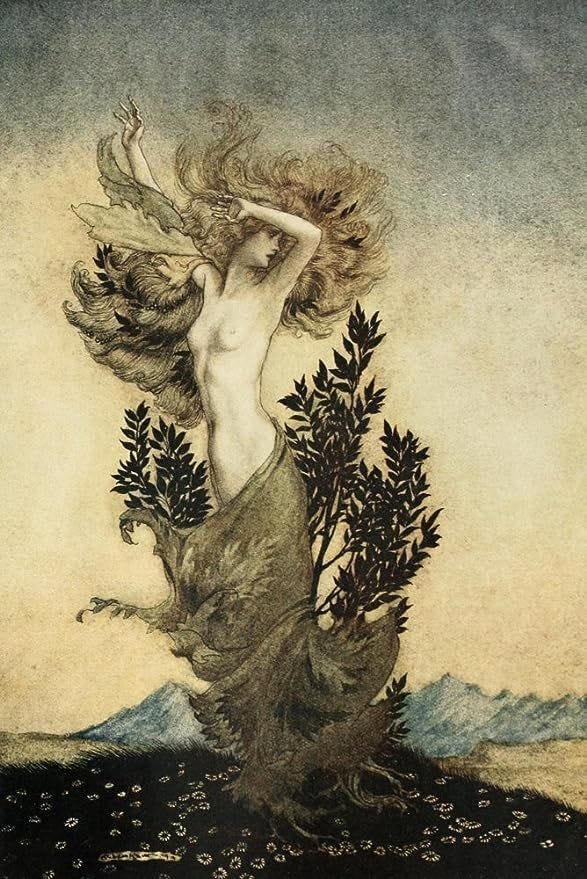

Arthur Rackham’s Daphne (1921).

Probably the most familiar story in this genre is of the naiad Daphne. Daphne was the daughter of Peneus, a river god, so we might visualize her as a minor tributary. Her beauty was famed, but she wanted to remain chaste, and she had the bad luck to attract unwanted attention from Apollo.

One of the morals of this story is: never mock the god of love! According to Ovid, Apollo had been making fun of Eros, saying "What hast thou to do with the arms of men, thou wanton boy?" The youth responded by firing a gold arrow at Apollo that made him fall in love with Daphne, and a lead arrow at Daphne that made her hate Apollo.

Maddened with desire, Apollo pursued Daphne, who fled his advances. Finally, she called out to her father Peneus to save her. The river god could not fight Apollo, but he transformed Daphne into a laurel tree. Apollo was dismayed when she become truly unattainable, and he used his powers to make the laurel’s leaves evergreen. At the Pythian Games held every four years in Delphi in Apollo’s honor, laurel chaplets were given as prizes, and it later became customary to award them to victorious generals, athletes, and poets.

Another nymph who became a tree was Pitys, who turned into a pine tree while fleeing from Pan. Pan also pursued another nymph, Syrinx, and she was turned into reeds in order to escape him. Pan then adopted her reeds for use in his panpipes. There was also Syceus, a Titaness who was metamorphosed into the first fig tree in order to escape unwanted attention from Zeus.

Pitys, a bronze bust by Cat Vitebsky. Each sculpture in the series is unique, because the artist uses a technique of experimental burnouts of local flora, as a twist on the classic lost wax casting method.

You know who else was closely integrated with trees? Lilith.

All right, all right — I said I wasn’t going to mention her again here, but here goes: the huluppu tree growing on the bank of the Euphrates River that the ki-sikil-lil-la-ke was perching in was a willow that sheltered Lilith and other demons. Lilith escaped after Gilgamesh chopped down her tree, but the snake that was immune to magic spells who was living in its roots was killed. (And this is another way that this story seems to foreshadow the story of Adam and Eve and the serpent, who is not killed, but is condemned to eternal enmity with the woman and her offspring [Genesis 3:15]).

Alpheus and Arethusa, Abraham Bloteling, engraving (1640).

Arethusa (called Alpheias by Ovid) was another case of a nymph who was absorbed into nature, but she — like Egeria — was turned into water. Once, she had numbered among Artemis’ chaste companions, but one day Arethusa came across a clear stream and began bathing, not knowing it was the river god Alpheus as he was moving along his course from Arcadia to the sea. He fell in love during their encounter, but she fled after discovering his presence and intentions. After a long chase, she prayed to her patron goddess to ask for protection. Artemis hid her in a cloud, but Alpheus wasn’t going to be deterred so easily. Trembling in fear and sweating from every pore, Arethusa melted into a stream. Artemis then broke the ground, which finally allowed Arethusa to give Alpheus the slip. As a stream, she traveled under the sea to the island of Ortygia (Syracuse, Sicily), but in the end it was in vain: Alpheus flowed through the sea to reach her and mingle and unite with her waters.17

It wasn’t just nymphs and Titanesses who could be turned transformed into other classes of beings — sometimes it also happened to humans. The story of Dryope tells of two such metamorphoses: she was turned into a nymph — a great honor — and some other foolish people became pine trees.

Dryope was a mortal princess who had made the acquaintance of dryads while she was tending her father’s flocks. The nymphs taught her to sing hymns to the gods and to dance. This gained her the attention of Apollo. His strategy to woo her was turning himself into a tortoise, which the girl and the nymphs made into a pet. They took turns playing with the tortoise, and when Dryope had the animal on her lap, Apollo transformed into a snake. The nymphs took fright and abandoned her, and Apollo raped her. She gave birth to his son, and when he grew up and became the king, her old dryad friends came to see her again.

Dryope was changed from mortal to nymph. [Her son] Amphissos, in honour of the favour shown to his mother, set up a shrine to the Nymphai and was the first to inaugurate a foot-race there. To this day local people maintain this race. It is not holy for women to be present there because some maidens told local people that Dryope had been snatched away by Nymphai. The Nymphai were angry at this and turned the maidens into pines.

-Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses 32 (trans. Celoria)

Compared with many Greek myths, this one has a very happy ending!

If you would like to support my work, you could

The conquest and subordination of nymphs

It’s clear that the identification of named nymphs as the indwelling spirits and protectors of certain places, and as the sources of wisdom and revelation that they would share with seekers predated humiliating episodes that downgraded their status. In the Classical age, the norms for unmarried women/goddesses/nymphs were that they should be chaste/chased, seen rather than heard, and not talked about outside of their roles as victims or serving patrism. (And in both cases, they should still be as invisible as possible.) In Pericles’ Funeral Speech, he says "the greatest glory for a woman is not to be spoken of at all, either for good or ill.

Yet, the downgraded nymphs weren’t simply prey: their prophetic skills were wanted by the higher divinities and by men, who either associated with them or appropriated their powers and/or took over their territories.

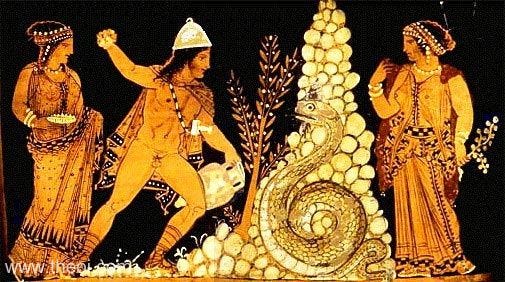

The illustration on this red-figure krater (ca 360-340 BCE, attributed to Python) depicts, from left to right: Harmonia, Cadmus (holding a water jug and preparing to throw a stone at the frightened dragon who guards the sacred spring of Ares, while the spring’s naiad protector, Ismene, watches in horror.

Re-reading Cadmus

Cadmus and his family and dynasty experienced many unfortunate incidents over the generations. Of course, it all began with the abduction of his sister, the maiden Europa. When her father sent the girl’s brothers to find her, Cadmus decided to do it the clever way, and he sought advice from oracle at Delphi to find out where she had gone. The oracle advised him to give up the search and, instead, to follow a cow with a half-moon on her flank till she fell from weariness. And then, right at that site, he should found a city. He sent his companions to fetch water from a nearby spring that was guarded by a dragon, but the dragon killed a number of them, so Cadmus slew it. Athena advised him to sow the dragon's teeth in the Earth; however, this created a corps of armed soldiers who sprang up ready to fight. Cadmus threw a stone among them, and they fell upon themselves until only five of the warriors remained. These survivors pledged their loyalty to Cadmus and offered to help him build Thebes. However, Ares was angered at the killing of the spring’s dragon and forced Cadmus to serve him as a penance for eight years. But the troubles were far from over for his dynasty …

Cadmus and Harmonia were married at a wedding attended by many gods, and Harmonia was given a cursed necklace by the smith Hephaestus. Their daughter Semele was blasted by Zeus; another daughter leapt from a cliff holding her dead son; and a fourth had her son Actaeon torn to bits. Their grandson Pentheus was torn to pieces by his own mother in a fit of Dionysian madness. Eventually Cadmus' great-grandson Laius became the king of Thebes. He married Jocasta, but learned from the Delphic oracle that he would die by the hands of his own child. When a son was born, Laius and Jocasta exposed him on a mountain, but the babe was rescued by a peasant who took him to a childless king who raised him as his own son and called him Oedipus.

While there are many layers to the story, and many possible interpretations, one could easily read the House of Cadmus cycle of myths as an account of the struggle between serpent-worshiping cults and cow-worshiping ones. We could say the same about Gilgamesh, the son of a wild cow goddess and a lilu, who killed several snakes in the course of his adventures.

A good discussion of the theme of cup-bearers can be found on this page. There is plenty more that can be said, and I believe the earlier layer of Indo-European lore that introduced cup bearers as a kind of subordinate retainer to a ruler is relevant, but this article is already long enough, so I will refrain from further discussion. (However, I do talk about about it a little in The White Deer.)

What was begun in the Classical era was taken much farther by Christians and — later — by the Enlightenment project. It has been written by hagiographers that in 362 CE the emperor Julian the Apostate sent his personal physician Oribasus to visit the Delphic oracle, which had been destroyed, and there he received the Pythia’s last prophecy:18

Tell the emperor that my splendid hall has fallen to the ground.

Apollo no longer has his house, there is no more oracular laurel,

nor his prophetic spring; and the voice of the water has been silenced. All is finished

However, despite Julian’s valiant attempts at restoring paganism in his empire, this text is certainly a later Christian epitaph that attempts to seal the temple, the oracle, Apollo and the Pythia, and even the spring into a silent vault.

Some lore, of course survived, and there were periodic revivals of interest in Classical myths, but the efforts at deprecating it were unstinting. Yet, many felt that without them something was missing: T.S. Eliot twice declared “the nymphs are departed” in the Fire Sermon section of The Waste Land — and he ends the section with a quote from St. Augustine’s confessions to make it clear why.

Apace with the Christianization process, all anthropomorphic goddesses and female chthonic/spiritual forces were turned into “fairies, demons, and nature spirits” — or sometimes ”small gods,” as this excellent anthology from Springer styles them. Beings of this kind were often reinterpreted as ill-disposed spooks and bogeys. As Robin Artisson remarked, this happens “when your culture's deep animistic past is so completely and thoroughly forgotten that all you have left is monsters and demons who have nothing better to do but hide in your wells trying to hurt you.”

Or, perhaps, if the nymphs were still imparting the same kinds of wisdom and inspiration they had shared with King Numa and with priests and poets in the old times it was interpreted as evil and madness by those who longed to connect their souls with heavenly rather than earthly powers.

A Nixie in the Well Frightens an Old Woman, by R. M. Eichler. Illustration for Jugend magazine (1898).

In urban and literate circles, fairies and nature spirits were either trivialized, or mainly recognized as the culture of “simple” and “backwards” country people. Thank goodness there were a few, such as the Brothers Grimm, and F. X. von Schönwerth who collected this lore.

However, outside the cultural mainstream there were always a few weirdos who still wanted to truck with water spirits: alchemists.

Female water spirits in alchemy

Hydriel ("Strength of Water"), from an 1849 edition of Magia Naturalis Et Innaturalis; or, the Inscrutible Hell-Companion.

Inevitably, of course, there was syncretization and abstraction away from original sites and rites, so that, according to the volume mentioned above, “The gentle mermaid is Hydriel (‘Strength of Water’), a fallen angel and demon, is third of the twelve ‘wandering dukes’ or princes of Hell; or she is the 13th spirit, leader of the Twelve Dukes … In late medieval demonology, she is the spirit of water, leader of 100 Great Dukes and 200 Lesser Dukes that dwell in the sea, in cloudy air, in swamps, and all wet places.”

There was also a new Modern spirit that sought to instrumentalize these entities, which were not to be sought at riverbanks and wells, but could be achieved by conjuration using planetary signs and controlled with Solomonic seals. They were not sought out for wisdom in arranging human relations with the land and water, but for the alchemists’ self-improvement: “They probably had a tantric purpose at an early level of their mystic doctrine, since to learn the names of all of them and recite them in a calm state was conducive of meditative process.” (From the 1612 edition of the grimoire Magia Naturalis Et Innaturalis; or, the Inscrutible Hell-Companion.)

Illustration from Rosarium Philosophorum (Rosary of Philosophers), an alchemical treatise published in 1550.

The crowned mermaid is usually identified with the snared siren-goddess Melusine, caged in her bath, whose liberation is required if knowledge is to be obtained. She might additionally be identified with the Faustian demon(ess) Hydriel who manifests as a mermaid.

Here she possesses serpent in grail goblet. The serpent-grail is the container for the elixir of life mixed from serpent's blood and venom. She has wings of cold and hot, black and red, moon and sun, emblems of harmonized opposites. She hovers above Water and Fire, and beneath the Garden.

Another late medieval portrait of this crowned mermaid gives her three faces, no wings, but she holds the Sun and Moon one to each hand, and is associated with a Golden Berry patch. Poisonous berries and hallucinogenic herbs were significant alchemical ingredients to induce altered states of awareness. Bright red berries were also used in brewing melomel, a variety of mead high in alcohol content and which looked like blood.19

Captive merpeople depicted in a watercolour illustration from the alchemical manuscript Clavis Artis (Germany, late 17th-early 18th c.), attributed to the Persian Zoroaster (Zarathustra). They represent a union of earth and water.

Meeting the nymphs and naiads

Perhaps alchemical experiments aren’t your thing, but you’d like to meet your local naiads. Ancient people sometimes left offerings for them in their waters or set along the banks of streams and ponds: coins, jewelry, figurines, flowers, and even sacrificed animals might be given over in the hope that the naiads would bless their donors with healing, inspiration, gifts, magic, blessings, ritual cleansing, or safe passage. And even today, many people still bring gifts like these to the healing wells and fountains under the care of saints and martyrs.

Traditional sacrifices offered to nymphs (not necessarily water nymphs — any of them,) usually involved goats, lambs, milk, and/or oil — but never wine. So I would suggest that you keep your libations non-alcoholic, and certainly do not leave anything at the site that will be persistent or might cause harm. (This includes “clooties” — pieces of cloth tied on tree branches, and also the construction of cairns — stacked stones.)

A very small amount — like maybe a tablespoon — of apple or beet juice (or another locally sourced juice) or of mineral or well water could be offered by pouring it on the ground near the water. Alternately, you might leave a few flowers or leaves on a riverbank, or read/recite/compose a poem in honor of the indwelling spirits. You might also offer them service by cleaning up any litter on the site.

If a usually free-flowing stream or spring is clogged by natural materials, you may be able push them aside so it can once more run joyfully along its bed using your hands or a stick — or, if you know the site wants attention, you might bring tools.

After you have made your presence and intentions known, if all is quiet, try going into a light trance and seeing if you can visualize the nymph of the place. If so, ask her name and whether she has any requests of you as a visitor.

Water Spirit, by LittleRainBlob on DeviantArt.

Water holidays

Some days are held to be sacred for the powers of the waters in certain cultures. You might live near a holy well, for instance, that has certain days and rites associated with it.

Where I live, in the Czech Republic, children are often led by their preschool or elementary school teachers to clean up springs on the Vernal Equinox or close to May 1. And there is still the echo of an old tradition on the 18th and 19th of January: Vodokres.

Sources vary on the origins, with Christians claiming the tradition arose in Theophany/Epiphany and Jesus' baptism by St. John the Baptist (Julian Calendar). Slavic culture enthusiasts say all of this is an overlay over ancient Slavic customs, and New Age types attempt to update the old lore of Living Water, claiming that on these days it becomes alkaline, "ionizing," and a "biostimulator" that provides antioxidant protection because of constellations.

I visited the crystalline, refreshing Lívia spring in the Brdy Hills this January 19.

Another well known Slavic tradition is Kupala, the Summer Solstice/St. John the Baptist celebrations that always take place by water and involve fire. Read more about the Polish celebrations here.

See here for a small trove of East Slavic customs — or don’t! You can research other traditions from your locality, or from history, or you can simply ask the indwelling spirits near you how they would like to be honored, and, as you imbibe their sparkling waters, fully appreciate the life-giving powers they share with you and all the myriad beings around you.

Magick Terrain, by David Bez (2023).

For a nuanced discussion of ways to classify nature spirits, see Lee Morgan’s excellent Sounds of Infinity.

Getting an accurate census of nature spirits and pinning down their genealogy can be tricky. You read about the 6000 Oceanids and Potamoi above, but then there was also the “Old Man of the Sea” Nereus and his wife, the Oceanid Doris, who were the parents of 50 Nereids 50 Nerites. These friendly merpeople were associated with the Mediterranean “inner sea,” and liked to keep Poseidon company. Sometimes, they would give aid to heroes, such as the Argonauts’ quest for the Golden Fleece.

Detail of a mosaic depicting the head of Oceanus, in the Baths of Themetra near Sousse (early 3rd century CE). Look at those adorable little corals and lobster claws where horns/antlers might be found on other deities’ heads.

King Arthur obtained one sword from a stone and another — Excalibur, or in its Latinized name, Caliburn(us) — from the Lady of the Lake. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae ( History of the Kings of Britain), which was written around 1136, describes it as “an excellent sword made in the isle of Avallon.” In older versions of the tales the sword itself did not have magical powers, but was a symbol of his prowess as a warrior, which he proved by using it to slaughter many foes in battle. This article briefly traces out some of the main storylines, but I do not want to linger any more on the Arthurian stories here. I will only point out that Arthur was a very warlike king by contrast with peaceful Numa, and that Egeria’s advice was intended to be used to found a good social order, not to personally empower one specially favored warlord.

Dennis: “Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for a system of government. Supreme executive power derives from a mandate from the masses, not from some farcical aquatic ceremony.”

Arthur: Be quiet!

Dennis: You can’t expect to wield supreme executive power just ’cause some watery tart threw a sword at you!

— Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975)

Another example of a nymph who served as prophet and the attributed author of sacred books was the Etruscan Vegoia, who is credited with having written the Libri Fulgurales used to interpret the will of the gods through lightning strikes. Egeria, too, facilitated communication with deities by interpreting omens.

The nymphaeum had large basins of water with fountains, purpose is uncertain, perhaps ritual purification. Often found in front of the temples. Hers is located higher than the temple, different level, not easy to proceed from nymphaeum to temple. Rites of passage were probably held for young brides (nymphae).

The oldest testimony to a relationship between Numa and Egeria comes from Ennius’ Annals (second century BCE).

A numen (plural: numina) was a divine presence, will or mind; particularly one that was indwelling at a particular place or in a feature of the land or water. Numina could be present in a wood, a river, spring, or cave, but also in the crop ripening in a field or abstract ideas such as Discipline (the goddess Disciplina), Virtue (the goddess Pietas), or Trust and Honesty (the god Sancus). Individual people had a genius (if they were male) or a juno (if they were female), as well as household spirits called lares and penates — and even today, everyone knows the spirit of a place was its genius loci. Here's a good summary of the main Roman numina.

Some have suggested numen is an action noun composed of *nuō for *nuimen, from *nuō + men, thus meaning "a nodding of the head" — the radiant gist being that the numen is a manifestation of divine will/the will of the gods. However, others propose an etymology derived from the ancient Greek word νοούμενον [nooúmenon] ("an influence perceptible by mind but not by senses"), from νοέω [noéō], which was borrowed into Early Latin as the word noumen, and whose spelling changed to numen in Classical Latin. Or, simply, from Greek words for law and custom — and yes, Numa Pompilius’ name is probably derived from this root.

For instance, Numa Pompilius is credited with establishing the Vestal Virgins, who were considered protectors of Rome, as well as the cults of Jupiter, Mar, and the deified Romulus (conflated with Quirinus), and even the office of pontifex maximus — a title inherited much later by the Catholic popes. Numa was considered a peaceful counterpart to the more aggressive Romulus who had (mythically) preceded him. Of course, the cults and institutions had actually developed over the course of many years.

The Bacchantes — follower of Bacchus/Dionysus — wandered from their home in Phocis during their night’s revels and woke up in Amphissa looking like they’ve got a bitchin’ hangover. Oy! As Plutarch described, the cities of Amphissa and Phocis were at war, but the women of Amphissa graciously offered the Bacchantes nourishment and protection, and Alma-Tadema intended this as a lesson in charity and fellow-feeling for his Victorian audience.

See Wendilyn Emrys’ M.A. thesis: The Transformations of a Goddess: Lillake, Lamashtu, and Lilith, which is available at Research Gate to view or download.

The photographer provides the following commentary, from the information provided for this exhibit at the Musee d'art et l'histoire du Judesime.

The origins of Lilith are in doubt: it may go back to a female demon of the Assyrian mythology Lilu or Lilith, or to a goddess of the night (the etymology of "Lil" is close to the Hebrew word Lamed Yod Lamed, Layill). In the Jewish world, she is said to be either the spouse of Samael, "Prince of the fallen angels," or Ashmedai, king of the demons. Many Jewish sources consider her as the mother of all demons. She is mostly depicted as an aggressive character, with disheveled hair, outstretched arms and bound feet. As an archaic creature, her femininity is enhanced by very prominent breasts and genitalia. Other images show her broad-hipped, thus referring to her fertility. By representing her naked, the designer of the bowl probably was seeking to humiliate her, and scare her away.

Like Dame Ragnelle, a figure I discuss at great length in my book The White Deer. I also discuss the animalistic and sexual but unsexy aspects of Medusa in "Medusa as a Loathly Lady“ here on Substack. See this paper for more discussion of Lilith’s aspects I mentioned in the text above.

This triptych of Lady Ragnelle is from Yuri Leitch’s Well Maidens of the Summerlands page. It makes an explicit connection between this shapeshifting character and the water guardian of Hartlake Moor.

Quiteria’s name is also conspicuously unusual. Some believe it may be derived from Kythere (alt: Kyteria, Kuteria), a title applied to the Phoenician goddess Astarte, which meant "the red one,” or from (the possibly related name) Cytherea, one of Aphrodite’s epithets that refer to her birth on the island of Kythira.

Alternately, Alpheus was a hunter. The story begins in the same way, but without the sweaty episode. Artemis wraps Arethusa in a cloud and takes her to Ortygia, where she transformed her into a spring of gurgling water. Alpheus wandered around, desperately searching for her. Zeus took pity on him, and un-cock-blocked the hunter by transforming him into the great river of the Peloponnese, whose waters, when they flow into the sea, cross the sea and reach Sicily, where they unite with Arethusa’s stream.

A good discussion can be found on this page dedicated to well maidens and cup bearers. There is plenty more that can be said on both topics, and I believe the earlier layer of Indo-European lore that introduced cup bearers as a kind of subordinate retainer to a ruler is XXXX, but this isn’t the place to open up that discussion. I do talk about about it a little in The White Deer.

What a rich and evocative piece Melinda! There's so much good stuff here, so many paths to follow and hints to chase up that I don't even know where to start!

Perhaps just one little note, in passing, to bring my own culture and legendarium to bear: in Ireland, holy wells, streams, lakes, rivers, and seas all had their Goddesses and Indwelling Spirits too; the most important perhaps being the Four Great Rivers, which came from the central and mystical Well of Segeais, overhung by the hazel-trees whose nuts gave prophetic powers, eaten by Salmon of Knowledge (plural) one of whom was caught and cooked by Fionn MacCumhail, granting him insight and vision. The River-Goddesses included Boann (the Boyne, in whose valley is Brú na Boinne, her redoubt: the famous Newgrange Passage Tomb) and Sionnan (the Shannon, Ireland's greatest river). You mention in The White Deer, I think, the Bean Níghe, the "Washer at the Ford", special case of the Bean Sídhe (Banshee), avatar of earlier Sovereignty Goddesses. Worth noting also is that the Goddess (and later Saint) Bríghid, shares with these Nymphs her association's with holy wells, healing, childbirth and abortion, inspiration, vision, and poetry. There are also any number of Faery Women and Animal Brides associated with bodies of water, from Fand, Faery Wife of Manannán Mac Lír, and Sea Goddess, to the Children of Lír, transformed into swans, and Caer Ibormeith, the Swan-maiden sought by Wandering Aenghus (son of Boann and the Dagda, incidentally...).