Medusa, Part II - it's snakes, baby, all the way down!

Birds, snakes, severed heads ... where did things go wrong?

This contemporary envisioning of a goddess does not depict Medusa (or Eve). Who is she? You’ll find out toward the end of this article.

In Medusa As a Loathly Lady - Part I, I recapitulated some of the best-known versions of Medusa’s myths and discussed more recent feminist applications of her story.

Here I will go much farther into the past and propose some unconventional connections.

CW/TW: Lots of snakes !!!

I like snakes — sign me up!

Athena’s secret

According to Pseudo-Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca, one day Athena went to visit Hephaestus to commission some weapons. When he saw her, the smith god was so overcome by desire that he tried to seduce her right there in his workshop.

Athena Scorning the Advances of Hephaestus, by Paris Bordone, (ca 1555-1560).

Athena wanted to preserve her virginity, so she fled — and Hephaestus pursued her. When the powerful smith caught her he attempted to rape her, but she was strong enough to fight him off. During the struggle, his semen fell on her thigh, and Athena, in disgust, wiped it off with a piece of wool that she threw down on the earth. However, as Homer wrote in the Odyssey, “a god’s embrace is never fruitless,” and a baby boy, Erichthonius, was conceived from Hephaestus’ seed that had fallen onto the ground. (Let us now pause for a moment to recall the unusual manner of Athena’s own birth: one of the most common versions of the story she was freed from her father Zeus’s head when Hephaestos split it open with his axe; he was, in a sense, the “midwife” who delivered Zeus of his daughter.)

This ill-conceived child put Athena in a dilemma: she couldn’t abandon the infant, but she also didn’t want anyone to know what happened to her.

In this red-figure stamnos, Athena is taking baby Erichthonius from the hands of Earth mother Gaia (470–460 BCE).

She put the baby in a basket and handed the little bundle of joy over the three daughters of Cecrops, the autochthonous first king of Attica, warning them not to look inside. One princess managed to curb her curiosity, but her two sisters did not. What they saw inside the box was either a snake coiled around a baby, or a baby that was half-human and half-serpent. Whatever it was, it allegedly drove them mad and they threw themselves off the Acropolis.1

Erichthonius Released from His Basket, by Antonio Tempesta (1606)

When he grew up, Erichthonius deposed pretenders to the throne and became the legitimate king of Athens. The snake was his personal symbol, and he was represented in the statue of Athena in the Parthenon as the snake hidden behind her shield.

And this is all pretty interesting, if you reflect on the punishment Athena meted out to Medusa for the “crime” of being raped. To wit: Athena’s “shame” remained hidden, and she benefited from it in multiple ways — with a son who did her honor,2 and another layer of snakiness in her personal device — but she made sure Medusa’s “shame” was known by all.

This in my view, smacks not so much or “hypocrisy” as usurpation. (Or, at the very least, “appropriation” of older cultures. I suggested in Medusa Part I that Athena may have always been after the powerful head of Medusa, and the story of the rape, the disgrace, and the slaying of the “monster” were a long game played to get it.

The Gorgoneion

The Gorgoneion — the Gorgon’s head symbol — has been popular since the Archaic period in Greece, but its distinct elements surely predate even the oldest recognizable Greek forms.

In Greek culture, Medusa’s head was always-already severed from her body: Homer, for instance, refers to the Gorgoneion four times, but never to the body of the head’s former owner.

Recognizable Gorgoneia are first found in Greek art in the early part of the 8th century BCE in coins discovered at Parium and Tiryns. The symbol then became ubiquitous, appearing on temples, statues, weapons and armor, clothing, jewelry, cups and dishes, and roof tiles. The Gorgon’s head was considered apotropaic, and those who wore it or put it on their home, on everyday objects such as vases and drinking cups, or used it in other spaces believed it would ward off “evil.” 3

One of the unusual aspects of the way the Gorgon’s head is depicted is the full-frontal view of her face — Greek art usually doesn’t depict characters that way! Perhaps that’s because it’s based on much older styles of representation. But it also makes sense if the object is to function a shield — you don’t want the power radiating from its eyes to be aimed anywhere else than directly ahead.4 Maria Tatar explains one of the etymologies of Medusa’s name:5 Μέδουσα, which is the present participle of the verb μέδω, means “to protect”— so her name can be read as “guardian” or “protector.” Perhaps this is how many understood the meaning of the Gorgononeion, but we will have to dig a lot deeper into why that would have been the case. (See the footnote above for more etymologies.)

Legitimacy and authority are always relational, and gods and heroes who used the Gorgoneion in their armor or regalia were borrowing legitimacy from the older powers represented in their symbols.6 Kings, such as Alexander the Great (depicted below in a mosaic), who used the device were borrowing from the gods, and ordinary people who used it in their homes or personal belongings also wanted a little power and protection on their side.

Clearly, Medusa/the Gorgons have to be much older than the putative origin story in the Perseus tales. (How far back does Perseus go? Nobody knows — but it must be pretty far, because even the etymology of his name is murky.)7 These two characters very likely developed separately and were brought fatefully together at some point close to the time when Hesiod and Homer were writing.

And there’s more to the story about Athena and her distinctive talisman that I want to touch upon before continuing. You see, the snakes on Medusa’s head were not the only serpents that made up the protective power of Athena’s famous aegis. Accounts vary on its other construction materials: perhaps a special goatskin; others speculate about thunderstorms. But another strong contending theory is that perhaps it was made from snaky, scaly dragon skin. In the Iliad the aegis was described as producing “a sound as from myriad roaring dragons,” which unites the dragon and storm themes.

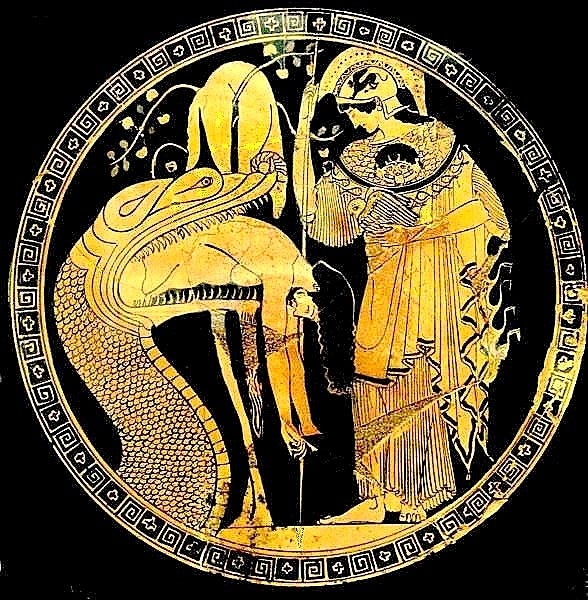

Athena wearing the aegis as a breastplate. Notice how its texture matches the skin of the serpent who guards the Golden Fleece (in this scene, he’s regurgitating Jason); cup by Douris, early fifth century BCE. Other versions of the aegis’ origin are that it was taken from Aex, a dragonlike daughter of the Titan Helios.

Virgil agrees that the aegis had snaky qualities, and describes it thus: “a fearsome thing with a surface of gold like scaly snake-skin, and the linked serpents and the Gorgon herself upon the goddess's breast — a severed head rolling its eyes."

When the Hellenic culture was absorbed by Rome, the popularity of the Gorgoneion increased dramatically, but — as I described in Medusa - Part I, they also lost a lot of their shock value. Archaic images of the Gorgon’s head were ghastly, with bulging eyes, sharp teeth, and a gaping jaw with the tongue stretched out, but they were gradually domesticated and became pleasant, beautiful, and even cute. Though there were always some who believed the newfangled Gorgoneia had far less power than the older images.

They just didn’t make them like they used to! This kittenlike Gorgoneion fashioned from opaque glass paste is just too darned cute to scare anyone. (Roman 1st–2nd century CE.)

The Gorgoneion as a mask of death

What, exactly, is frightening about a Gorgon? Some reflexively say it’s the snakes, but I’m skeptical, given serpents’ widespread presence in the ancient world in the body parts and symbolic repertoire of all manner of deities. Sure, snakes can be dangerous and even deadly. So can dogs, cattle, or bees. However, snakes have a host of other associations as well, such as abundance and fertility, and actual serpents were commonly kept in shrines and even in households in the ancient Mediterranean.

What was frightening about the Gorgon’s visage was not its animal aspects, but the deformation of its human ones. Anna Lazarou and Ioannis Liritzis refer to S.R. Wilk, who suggests what could have inspired the archaic Gorgoneion’s hugely bulging and staring eyes, flattened nose, wide opening of the lips with clenched teeth, swollen protruding tongue, extreme (swollen) facial expression and stylized hair: the condition of an unburied corpse one or two weeks after death.8

As is well known, after death the body undergoes alterations and changes: its temperature drops, the blood stagnates and stiffness occurs, which later subsides. As the body’s defense against bacteria ceases to exist, sepsis begins, and within a week or two, bloating occurs due to the pressure of the gases created by the decomposition. The results of this procedure are shocking: the tongue begins to swell and come out of the snarling mouth. The eyes are also swollen and protrude from the eye sockets. Sometimes a bloody fluid is poured from the membranes around the eyes. The face swells, after all its features are deformed. The lips are repelled by the fangs. The strands of the hair are straightened on the forehead and scalp. In other words, the person begins to acquire the characteristics of a “gorgoneion” …

And it’s scary, because it shows us the transformation of a human into an image of death. In the gorgoneion, however, the most abhorrent aspects of the death process have been softened. The eyes are enlarged but not repulsive, and they are not forced out of their sockets in an absurd manner. The protruding language is neater. The swelling of the face has been attributed to a flattened nose and large cheeks. Hair separation has turned into stylized curls and skin lesions into normal spots and lines. The set has become more acceptable.

The Gorgoneion thus forces a confrontation with death (and perhaps an ancient goddess associated with its mysteries); though there is still a powerful ambivalence. On the one hand, death has been tamed and somewhat cultured. Its features are legible instead of just presenting a disintegrating mess. On the other hand, in order to work as an apotropaic talisman that would ward off bad spirits and protect its owner from spells and bad luck, illness, enemies, thieves, etc., it needed to be frightening. Dilated pupils are a physiological reaction to fright (and to snake venom). So, whether or not the Gorgoneion represented a corpse, it did illustrate to viewers exactly how they were supposed to react to it.

We should also bear in mind that wide-dilated pupils can be caused by ingestion of many drugs, and Neolithic and Bronze Age religions often featured the ingestion of psychedelic potions which could contain opium, cannabis, henbane and other nightshades, mushrooms, ergot fungus — and much more. A person participating in such rituals would have beheld the spectacles presented to them in dark, torchlit chambers and masked priests presented divine mysteries and suggested myriad wonders, which they really would see with their own eyes.

A small terracotta Gorgoneion left as a votive offering at the sanctuary of the chthonic deities (Demeter, Persephone, and the Graces) just west of Orchomenos, Boeotia. 4th century BCE. Source.

However, religious beliefs can degrade over time to superstitions, nostalgia, and — eventually — to mere habit. Think, for instance, about the custom of saying “Bless you!” when a person sneezes. Or people who wear religious jewelry because it was a gift from an elderly relative. Over the course of centuries the significance of Gorgoneia in temple architecture waned, and by about 500 BCE, they were no longer used as decorations for monumental buildings; however, they were still commonly found at the entrances and on the roof tiles on smaller structures as well as on objects of everyday use. Because, after all, why not? Can’t hurt, might help.

The Gorgoneion would go on to enjoy popularity among the Roman emperors and Hellenistic kings who often wore it on their person, and It remained popular even in Christian times, especially in the Byzantine Empire.

Wealthy Romans were very fond of having Gorgoneia installed in floor mosaics. This example, with a hypnotizing frame around Medusa’s head comes from the Palazzo Massimo in Rome. Here is a gallery showing many similar examples. In this period, some patrons preferred to reintroduce some of the archaic elements, and others are letting them go — for instance, Medusa’s eyes no longer always gaze directly forward, but the psychedelic patterns around her still produce a dizzying effect. In one late example, her head has been replaced with Dionysus’ head, with the substitution justified, perhaps, by associations between intoxication and (temporary) petrifaction. If my suggestion above that part of the reason for the original feature of enlarged eyes is valid, it makes an interesting atavism that preserves the most important essence of this figure.

Bronze Sheet with Repoussé Decoration thought to depict a Gorgon’s head. CA late 7th c. BCE from the Kabeirion in Thebes. Source: Wikimedia

The Gorgoneion enjoyed a revival during the Italian Renaissance and it has remained popular ever since. Because it has so long been a symbol closely associated with royalty it was selected by the luxury brand Versace as their logo.

Let’s go back even farther … Neolithic Bird and Serpent Goddesses

Medusa, in her more archaic versions, has attributes of both birds and snakes.

The snakes never go away, but — as we have seen — her wings shrink and eventually disappear. What would we find if we went much farther back in time?

Marija Gimbutas identified certain figurines produced by European Neolithic cultures as bird-woman, serpent-woman, and even bird-serpent-woman hybrids. Bird-serpent-woman forms represent birth, death, and regeneration for reasons that ought to be obvious: both birds and snakes are oviparous (lay eggs), so both represent a principle of rebirth. Snakes hibernate for the winter and shed their skin; birds molt; mythical phoenixes do their thing — all forms of regeneration. A hybrid figure would have mastery of three worlds: earth, sky, and underworld (the realm of serpents and dragons), and when there was not a single bird/snake/woman as a focus, the roles could be differentiated. In any case, a close association with funerary rites and — probably — the mysteries of transition is borne witness by the location of so many of these finds being in gravesites.

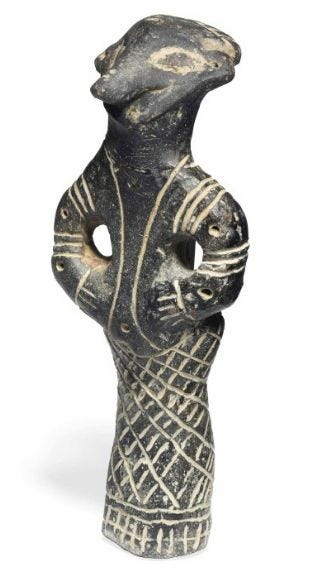

First, let’s look at this Vinča figurine, who has a very odd-shaped face and holes on her arms to which feathers may have been attached.

Below is another enigmatic Vinča statuette. The goofier parts of the blogosphere think these icons are proof of alien visitation.

Here is a Middle to Late Neolithic figurine from Crete:

This piece has been identified as a “prehistoric snake goddess” because it lacks feet. Perhaps it could represent a figure like Echidna who has two snaky legs. Does she have a bird’s head? It does seem that way. But often she’s just identified as “a squatting steatopygeous [large booty] woman,” so I honestly don’t know — people read a lot into these ancient figures.

Below are two early Egyptian figurines with bird (or snake?) faces and winglike arms. About 250 of these artworks dated to the Naqada period (4,000—3500 BCE) have been recovered. Most — though not all — are female, and some are pregnant and/or have animal features. The majority are made from baked clay, but they were also sometimes made from stone, ivory, or unbaked clay. This blog article has some good information and insightful commentary (so I’ll refrain from any further commentary about her Over-enthusiastic use of Capital Letters, and hope that posterity will forgive my Gen X penchant for alternating typefaces).

Because the images were almost entirely found in graves, it is likely that they had a specifically mortuary purpose. And dynastic Egyptians continued to make specifically mortuary goods—including Divine images. If these figurines were indeed Deity images, as I think they are, perhaps they were intended to represent early versions of some of the most prominent of the dynastic mortuary Divinities: Hathor, Nuet, Isis, Nephthys, Anubis, and Osiris.

Isis, or proto-Isis, is an ancient, ancient, ancient Goddess. She is the Death Bringer (for She is a raptor) and She is the Resurrector (for She is Great of Magic).

Goddesses with bird and snake attributes are plentiful in early historic religions, such as those of Egypt and Mesopotamia; therefore, whether or not there was a unity of myths at one time across a wide cultural area (i.e., Gimbutas’ “Old Europe,”) it is certain there were similarities and continuities in motifs and myths about powerful divine female figures in Europe and the Near East.

Winged Gorgoneion on a bronze shield device from Olympia. Early 6th c. BCE.

Potnia Theron — is she is, or is she ain’t?

The Potnia Theron (Mistress of Animals)9 motif was widespread in ancient art in the Mediterranean and Near East. The word Potnia is a Mycenaean Greek word inherited by Classical Greek; it is cognate to Sanskrit patnī.

This kind of goddess is always shown from the front grasping two animals, one on each side. The degree of symmetry in the composition can vary, and the web of relationships among what must have been different cults in different areas is obscure. The animals can be those hunted for game or wild creatures such as owls or lions that had symbolic but not economic significance — never livestock. Despite these differences among the images, you know one when you see it, and they are categorized as Potnia Theron regardless of their provenance.

There have been claims that a sculpture from Çatal Höyük represents the earliest example of this type, but I am unconvinced about the attribution, as the figure is corpulent, seated, and resting her hands on the beasts of prey as though in an armchair.

I mentioned and showed her because she so often appears on other blog articles with text that uncritically copy/paste monotheistic Great Goddess theories.

Let’s move on …

Mesopotamian religion had thousands of deities, but modern scholars are only able to define distinct iconographies for about a dozen of them, which makes identifications difficult. The image above is called the Burney Relief, or “Queen of the Night” (ca 1800—1700 BCE). Many spurious identifications with Lilith have been made {eye roll }, but the British Museum, where the terracotta plaque is displayed, prefers to identify the figure as Ereshkigal.10

However, what interests me the most is that this relief plaque was certainly a cultic object: symmetric compositions are found Mesopotamian art when the context is not narrative. This is because the image is not telling a story, but is intended to represent the presence of the deity and to be a focal point for worship. Clearly, people already knew who she was and were familiar with her stories when they arrived at the shrine.

A thousand years later, Homer describes Artemis using the title Potnia Theron.

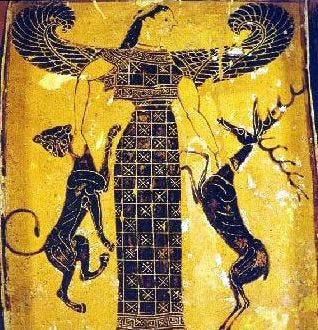

Archaic relief plate depicting Artemis Orthia in the Potnia Theron stance on an Archaic ivory votive offering. Found at Sparta in the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia, (ca 660 BCE).

Even in the High Archaic era Artemis was still sometimes depicted this way. Note the bird-of-prey wings!

Krater, Volute, signed by Kleitias (ca 570 - 560 BCE). Unlike the three-dimensional sculptures and the faces in Gorgoneia, Artemis’ face is turned aside but she is gripping her two animals by the neck like a classic Potnia.

What about … ?

Is the famous “Minoan snake goddess” a Potnia Theron? This image from ca 1600 BCE certainly has some of the correct attributes, but WTF is up with the cat perched on her head, and — altogether —the story of her discovery, interpretation, and reconstruction are so vexed that it’s difficult to say anything too definitive about who or what she represented to the Minoans.

Here is another Minoan figure, fashioned from chryselephantine. She, too, is holding two serpents.

And what about … ?

Who’s this? This votive terracotta plaque with its head in relief depicts a goddess flanked by two serpents. She was found amid some rubble in 1932 that was intended to be used as landfill in what was once the Athenian agora (public square). It took a long time for researchers to make a definitive identification.

Can you guess who she is?

Most likely, she’s Demeter! And that just goes to show the extent to which these deities and their iconography form a large and tangled web.

Below is a winged figure with a Gorgon's head who brings all of our themes together:

Her pose holding paired animals in her hands puts her firmly in the Potnia Theron category. The “swastika” symbols were called tetraskelion in Greek, and they were thought to represent the four horses who pull the chariot of Helios, the Sun, and to represent good fortune. Taking a wild stab, the pattern of seven dots that is repeatedly tattooed on her arms could represent the Pleiades. And the cross design on her leg may have been a funerary motif.11

Wikimedia identifies the figure on this plate as “Winged goddess with a Gorgon's head wearing a split skirt and holding a bird in each hand, type of the Potnia Theron” (ca 600 BCE). Some scholars have identified her as Artemis, but why would Artemis have a Gorgon’s head, and why would a Gorgon be a Mistress of Animals? And for that matter, why were there so many auspicious symbols layered on top of a “monster”? Whichever way you read it — or if you accept it as a syncretism — it looks a lot like Medusa had divine standing, at least at some distant point in the past.

Other Greek hybrids with bird and snake features

As we move into the Classical age in Greece, many figures who retained bird and snake attributes are classified as “monsters,” placed under the authority of fathers and husbands, or stigmatized with rape. Chthonic spirits of the land (daemons) are transformed into monsters and — much later — “demons” in the sense of evil beings once the Abrahamic religions start taking over. Or, sometimes, as angels, which did not take their familiar form as winged humans until the Byzantine era. (The history of the depiction of angels is interesting, as it represents a kind of contrary process to what I’m describing here.)

Funerary Siren (1st century BCE). This popular form of sculpture looks like a predecessor of later funerary statuary with angels. The ancient Greeks did not imagine sirens as sexy mermaids, as many have supposed. Instead, they were bird-women.

Below, Scylla on an Etruscan ash urn (late 3rd century BCE). She has a tiny set of wings on her forehead (as Medusa did in later representations) as well as on her shoulders, and a split snaky bottom. The conservative funerary context seems to have best preserved the ancient snake and bird elements as a single package.

Egyptian snake deities

Herodotus, who was a relatively late commenter, provided a Libyan origin for Medusa: as Perseus flew away with Medusa’s head in his bag, some of her blood spilled onto the hot Libyan sands. Each one became a deadly cobra.12 Does that mean he thought she was an import from Egypt?

While many cultures have snake deities, the Egyptians were extra fond of them.

Snakes were not only symbols of divinity in particular cults, but also of sovereignty, royalty, and the very idea of godhood, and their kingdom was founded upon this symbolism.

The Egyptian goddess Wadjet, the patron goddess of the Nile Delta and Lower Egypt, was depicted as a cobra. Often, though not always, she was also shown with wings.

Wadjet’s symbol, the Uraeus, was worn as a head ornament by the Lower Egyptian pharaohs, while the vulture goddess Nekhbet’s white vulture symbol was worn on head ornaments in Upper Egypt.

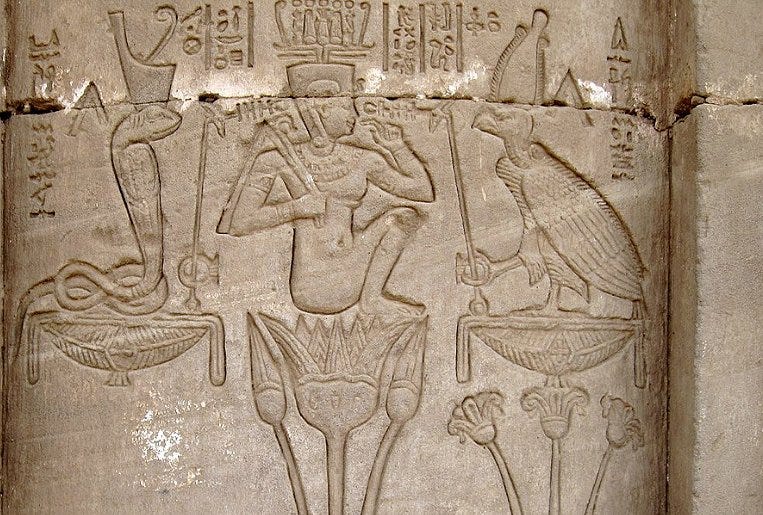

The god Nefertum on a lotus flower is depicted between the Ladies of the Two Lands — Wadjet and Nekhbet, each wearing the crowns of their kingdoms. Temple of Dendera, Roman period. The crowns will eventually be combined and called pschent, the "Two Powerful Ones."

When Lower and Upper Egypt unified in 2686 BCE, the pharaohs’ new head ornamentation incorporated both the cobra and white vulture heads, with the body of the cobra and the neck of the vulture entangled, symbolizing the unity of the kingdoms and of the cults of the Nebty (the Two Ladies).

King Tutankhamen’s famous gold death mask, which clearly displays the vulture and rearing snake. Imagine if the snakes were multiplied, as they are on Medusa’s head — yeah, that’d be a pretty badass crown.

The Uraeus was also a hieroglyph which could refer to a goddess or priestess, or to particular goddesses (e.g. Isis) or their shrines. Some myths also say the the Eye of Ra symbol, which was popular on amulets, was composed of two Uraei wrapped around a solar disc. Most importantly, though, the Uraeus was the most important symbol on a pharaoh’s regalia that granted him or her the power to rule Egypt.

Some Greco-Egyptian syncretisms

Stela depicting Isis as Agatha Tyche (Good Fortune) and Osiris as Agathos Daimon (Good Spirit) in serpent forms. A griffin holding a wheel of fortune is in the background. Sometimes, later, Serapis replaced Osiris in these kinds of depictions.13

Isis could appear in fully serpentine form, or as a half-serpent, as illustrated in this terracotta sculpture from the 2nd century CE. In this form, she looks a lot like Echidna!

Look who else got a snaky makeover (snakeover?) in Egypt — Dionysus!

Above: Roman marble relief found in Naukratis identified as Dionysus (1st century CE).

Greco-Egyptian syncretism fused Dionysus with Osiris as early as the 5th century BCE, and Herodotus comments in his Histories: “For no gods are worshipped by all Egyptians in common except Isis and Osiris, who they say is Dionysus; these are worshipped by all alike [...] Osiris is, in the Greek language, Dionysus.”

Dionysus-Osiris was particularly popular in Ptolemaic Egypt, as the Ptolemies claimed descent from Dionysus, and as pharaohs they had claim to the lineage of Osiris. This association was most notable during a deification ceremony where Mark Antony became Dionysus-Osiris, alongside Cleopatra as Isis-Aphrodite. Other deities that were created through the process of conflation are Serapis and Hermanubis.

Bottom line: unlike the Greeks, the Egyptians did not seem to have feelings of fear, aversion, or disgust toward serpent deities; on the contrary, they gave snakeovers to deities that weren’t previously represented that way and invented new ones.

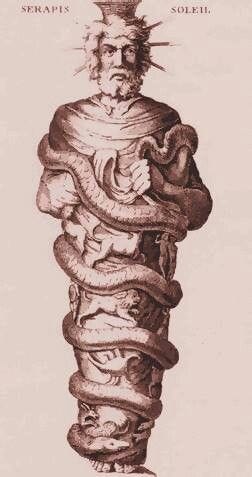

Copper statuette of Serapis/Agathos Daemon, Greco-Egyptian chythonic/sun/grain god (ca 300 BCE). Source. His cult helped unify Egypt’s Greek and Egyptian populations under the auspices of the Ptolemy dynasty.

The Greeks had little respect for animal-headed figures, so Serapis was increasingly represented either as a human-headed figure with a snake body, or even fully human but with snakes wound around his body.

Serapis’ main cult survived in Alexandria survived till the end of the 4th century. In 391 a Christian mob directed by Pope Theophilus destroyed his temple during one of the many religious riots that were so common in that era.

Serapis was adopted by some Gnostic sects who considered him a demiurge.

Domestic snakes in ancient Rome

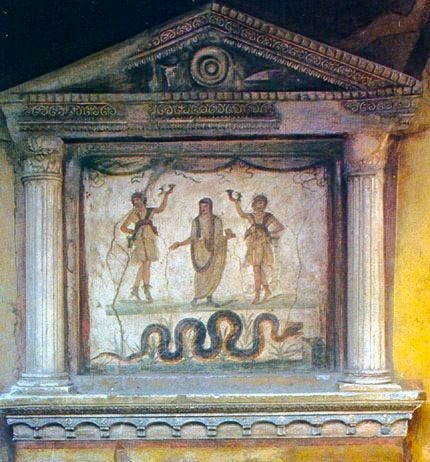

The Romans also commonly used snakes in their mythic imagery. For instance, they were found in household shrines (lararia), where they might represent Agathos Daimon or the family’s guardian spirits.

A pair of frisky dracones painted in a fresco in a villa interior in Terzigno, six kilometers from Pompeii. You can tell which is the male snake by his beard.

A typical Roman lararium is shaped like a temple. It features the lares holding raised drinking horns. These two youths are guardians who protect the household from external threats. Between them is the genius (who represents the spirit of the male head of the household) — he’s dressed in a toga and making a sacrifice.

To the Romans, snake imagery and real snakes weren’t creepy or spooky, which is how they still seem to North Americans or many Europeans today. Tame snakes were often kept in temples, but also in households where — like cats — they were in charge of eating rodents. House snakes were believed to help take care of the penus, or household provisions, but they also helped keep plagues at bay. This must have been well known, because Livy recorded how a delegation was sent to Epidaurus to bring back Aesculapian serpents to help deal with an epidemic.

Seneca also mentions guests’ pet dracones gliding among "cups and bosoms" at banquets, and Martial said that Glaucilla liked to twine a clammy snake around her neck (perhaps as a means of refreshment from the heat of Rome?) Makes sense, if the snake is OK with it! (Source.)

The ancient Slavs also kept snakes as household pets, and in Belarus, when storytellers want to emphasise that something happened long time ago, they would say "in the old days, when people kept snakes in their houses"...

How different from the approach in Genesis 3:15, where YHWH says to the serpent:

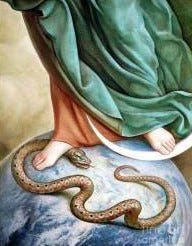

“I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed; she shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise her heel.”

Or in Luke 10:19: “Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you.”

Catholics picked up the battle cry against the Devil — the “enemy” mentioned in this texts — who they believed to be the true identity of the serpent in Eden. When Pope Pius IX promulgated the dogma of the Immaculate Conception in 1854 in his Ineffabilis Deus, he wrote: ‘The most holy Virgin, united with him [Christ] by a most intimate and indissoluble bond, was, with him and through him, eternally at enmity with the evil serpent, and most completely triumphed over him, and thus crushed his head with her immaculate foot.’”

Thus, Mary is very often depicted with a serpent beneath her feet. The moon under her feet symbolized “her victory over time and space”; alternately, it’s victory over Islam; or it’s a reference to St. John’s vision of the Apocalypse and “a woman clothed with the sun and the moon under her feet.” It may also represent chastity (recall Diana), but there’s also the Earth under her feet as well as — possibly the sun — and … well, let’s just stop here.

The Bona Dea and a counterfactual hypothesis

Here’s someone you may not have expected to meet in an article about Medusa: the Roman Bona Dea.

Bona Dea marble statue with epigraph. Wikimedia.

Bona Dea (Good Goddess) is a kind of code name or noa-name.14 It would be profoundly unlucky for me to tell you what I think her real name is, especially if you’re not a woman. If you’re desperately curious, go look it up yourself.

What I can tell you is that some of her epithets include: fatua, referring to her prophetic ability; igea, for the health she guaranteed; valetudo, to prevent diseases; oclata, or cautious; damiatrix, for sacrifices; opifera, for her industriousness; lucifera, “light”; and nutrix — mother. Five surviving inscriptions dedicated to Bona Dea also called her serpenas (snaky one).

She is usually depicted enthroned (regal), wearing a chiton and a richly draped mantle. Some of her votive inscriptions depict serpents, which are often paired — so you know she’s associated with good health, fertility, and abundance. On her left arm she holds a cornucopia to show her generosity. In her right hand, she holds a bowl, which feeds a serpent coiled around her right arm: a sign of her protective, healing, and regenerative powers. This combination of snake and cornucopia are unique to Bona Dea’s iconography.

Bona Dea’s cult was introduced to Rome after 272 BCE, and her sanctuary was built in the same century. The sanctuary was a center of healing in Rome. Domesticated snakes were housed in the temple, and there was a pharmacy where herbs and other remedies were sold by priestesses. Domesticated snakes slithered around in the temple. The facility was still in use during the 3rd century CE, but if it was still in use by the 4th century, it would have been closed during the waves of persecution against Pagans in the late Roman Empire. A church was put up in its place in the 5th century.

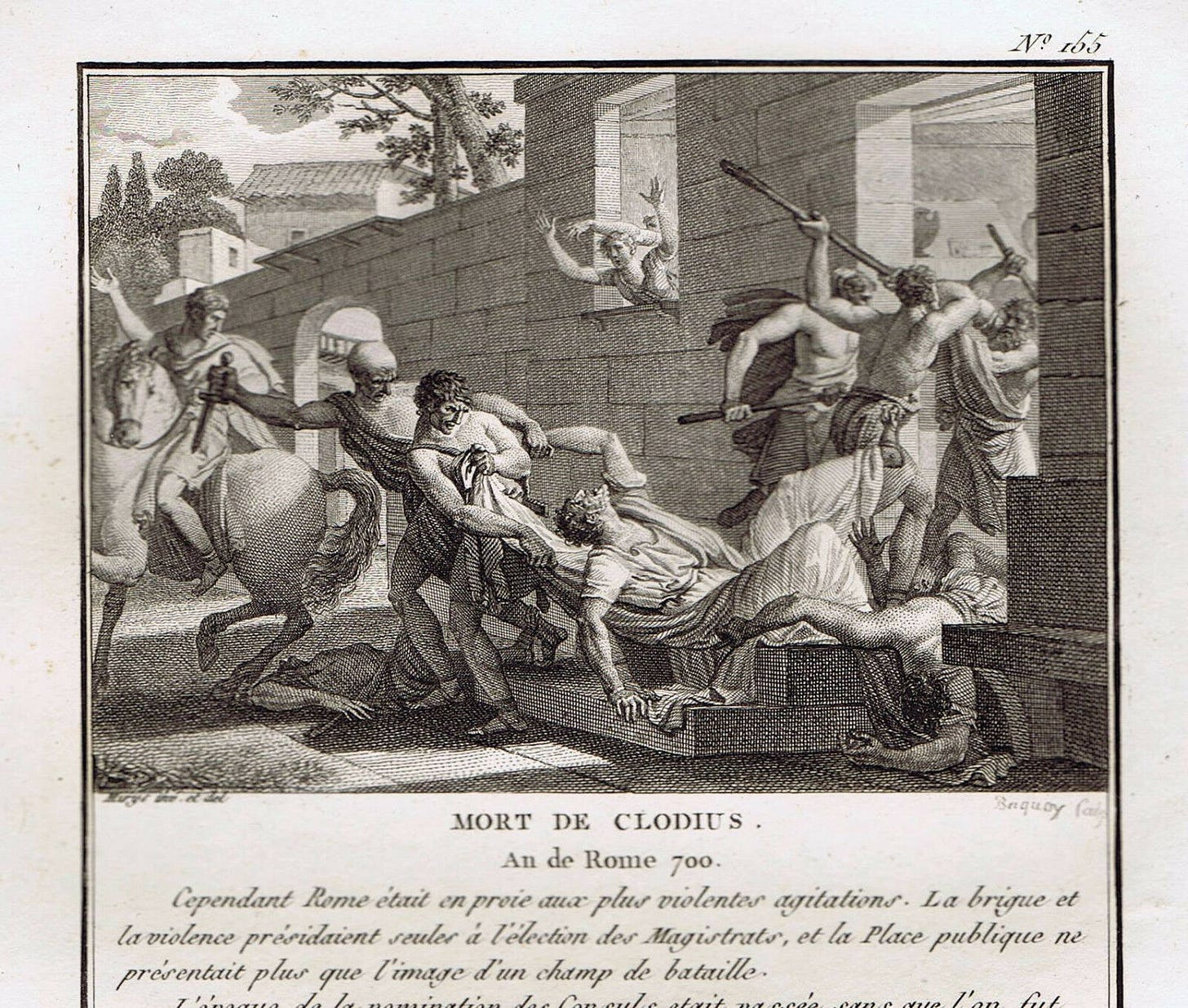

Women celebrated rites for Bona Dea twice a year: on May 1 at the temple, and in December at the home of the magistrate’s (highest official’s) wife. Men were strictly forbidden from attending either event. The proceedings were supervised by the Vestal Virgins, and men were terribly curious about what was going on — to the point where one jerk named Publius Claudius Pulcher caused a scandal that resulted in the Vestals having to redo the main rite.

After a life of brinksmanship and conflict, Clodius came to a bad end in a brawl outside an inn. Engraving by Silvestre David Mirys. (Wikimedia.)

Bona Dea was the only deity whose rites allowed women to gather at night, drink sacrificial (strong) wine, and perform a blood sacrifice (of a sow). There was also a symbolic repudiation of rape and domestic violence in participants’ strict refusal to have any myrtle present, or even to say the word. The magistrate’s wife and her assistants decorated her house with bowers of vine-leaves, and decorated the house's banqueting hall with "all manner of growing and blooming plants" (except for accursed myrtle). A banquet table was prepared, with a couch for the goddess and the image of a snake.

While these “ladies’ night” events were all too infrequent, and while Roman women really did lack many rights, in my view, this was a late survival of a healthy model of female sovereignty in the Western world. It would have been something to build upon, after so much had already been taken away.

Roman women (and their dogs) could also attend the Nemoralia (a celebration of Diana’s birthday) at Nemi. I discuss the Nemoralia at length in an earlier blog post:

1. Nemoralia: the Ides of August

A contemporary tapestry depicting Diana and her dogs, woven the the Portuguese tapestry artist Renato Torres (2020) Diana nemorensis Diana, originally Jana, a pre-Roman goddess of the woods, animals, and hunting, was Hellenized (assimilated) with the Greek Artemis and is often described as her “Roman equivalent.” She has been worshipped both singly and in…

However, the key difference I see between these suburban rites and the Bona Dea’s festivities is that celebrants had to leave town to celebrate the Nemoralia, while the Bona Dea’s temple was right on the Aventine hill and — more importantly — her December feast was held within the halls of the most powerful man in Rome.

Bona Dea, to me, represents female sovereignty, which was limited but also connected to ancient motifs and real power.

If Constantine had not backed the upstart Christian faith, or if Julian the Apostate’s reforms had stuck, Bona Dea’s cult could have been a powerful cell for female re-empowerment, especially as it was centered firmly in the highest stratum of elite matrons.

I cannot find a specific attribution for a person who co-created this AI image of Bona Dea. However, it seems to be the intellectual property of this page. She sleeps, guarded by her serpents, effortlessly bringing forth fruits and other good things, and perhaps dreaming of her cult being revived.

Etymological postscript

I have already discussed standard and alternative etymologies for gorgon. As for Medusa, some (e.g. Maria Tatar) translate her name as “protectress.” This is a valid derivation, and relates well to the themes present in the Gorgoneion, but the most typical translation of Medusa’s name is ruler (queen).

Etymologically, Medusa is derived from the PIE -med* and is connected with a range of meanings, including to rule, to provide for, to heal, to advise, and to judge. In English, our words medicine, measure, meet, mete, mediate, method, meditate, remedy, mold, and empty also come from this root ... Medea, whose name means “schemer” or “planner” in ancient Greek, has a similar origin, as does the Italian family name Medici, which means “doctors.”

I think these two long essays have shown plenty of reasons why all of these derived words still express aspects of the fascinating character of Medusa. As for medicine … let me tell you a story:

One of the myths tells that the blood from the right side of a Gorgon can be used to bring the dead back to life. However, the blood from the left side is a fatal poison. Athena is believed to have given Gorgon blood to Asclepius (the god of medicine and son of Apollo, whose symbol is two snakes twined around a staff). This enabled him to sometimes bring people who were on the brink of death to life, and it indicates why some other gods — particularly Hades — became very frustrated with Asclepius. They conspired decided to kill him, probably with a strike from Zeus’s thunderbolt. Either that or he was dosed with the left-side blood.

Complex syncretisms and a pale echo

The enigmatic Medusa was a uniquely Greek character who had many autochthonous Greek elements to her story. However, she also synthesized several other streams of influence, beginning with Neolithic Europe and including Indo-European and Semitic elements, and her stories and iconography evolved over time in connection with cultural values and aesthetic preferences. This single figure represents a very archaic death goddess, a mistress of animals who partook of avian, reptilian, and mammalian traits, and an embodiment of unsatisfied vengeance.

Medusa was granted the petrifying power of turning men to stone it was, in fact, she who was petrified. Under the spell of patrism and Perseus’ lust to found a dynasty, Medusa was forever frozen in her “loathly” aspect. Unlike in the Celtic tales, however, there was no chance that a prince would unlock her beautiful, bountiful potential and help the land to flourish. Perseus had entirely different plans.

Despite her attributed parentage (in the Greek tales) and probable status either as a deity or as a synthesis of deities before that, the Medusa we know was tragically mortal, and the encounter with Perseus is considered to be the end of her story – she does not regenerate or reappear, and her Gorgon sisters also exit the mythical scene. Like the loathly ladies in the Celtic tradition, the hero’s encounter with her is the precondition to his enthronement; however, there is one key difference: the ancient Celts did not have primogeniture. Their kings had to be chosen anew when the old one could not serve, and a new marriage with the indwelling powers of the land had to be enacted. This prevented the establishment of dynasties and the consolidation of too much power within one family. These are the traditions that Poseidon (as rapist), Athena (as the commissioner of the bounty hunt), and Perseus put an end to when Medusa is shamed and killed.

The Bona Dea and her cult, in my view, was a pale echo of the ancient symbols of initiatory mysteries, the archaic connection between serpents and well-being, and of autothonous sovereignty and female empowerment. And, by contrast with the mysteries of Medusa, the Bona Dea represented female alliances and power in ordinary reality.

Statuette of Bona Dea (Source.)

If you dig my style of research and writing, I think you’ll really like my book The White Deer: Ecospirituality and the Mythic.

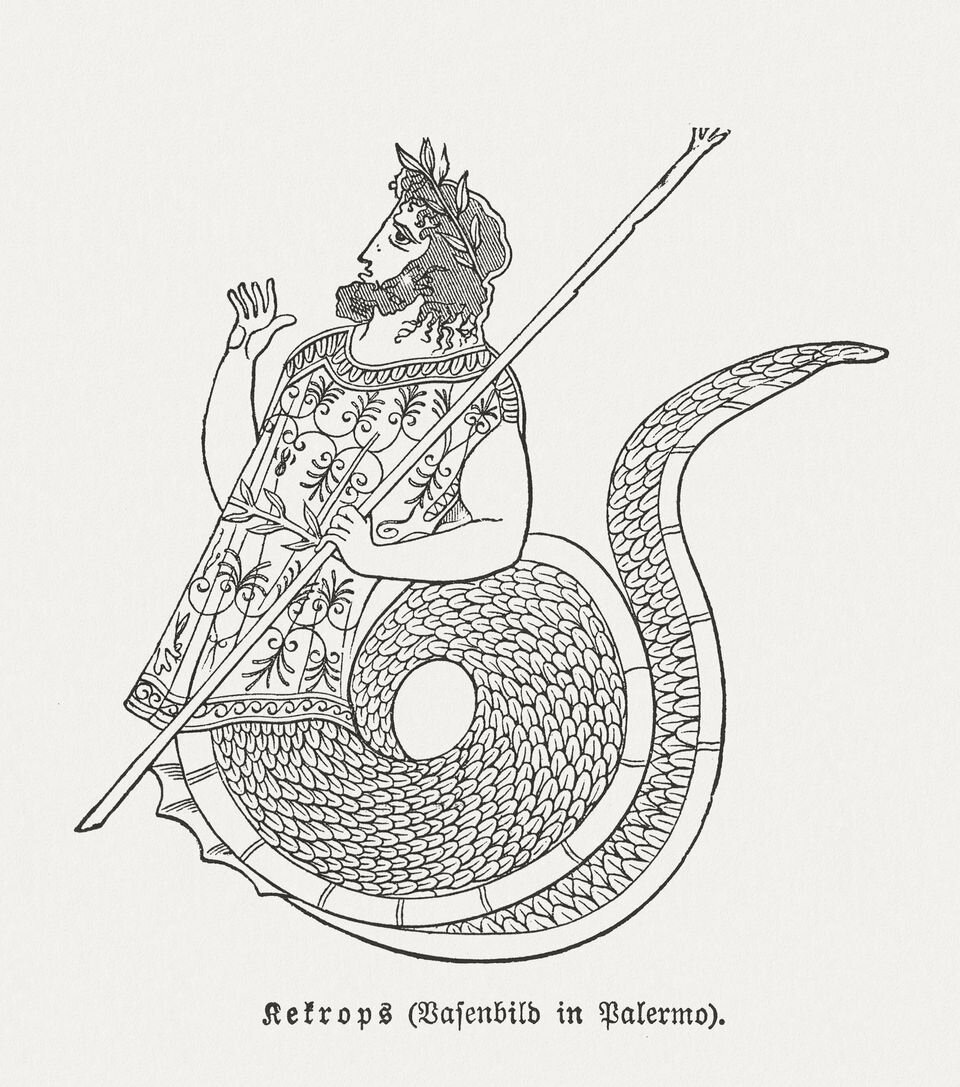

What? What?!? How could a half-snake baby possibly faze these girls? It made all the sense in the world that Athena handed her baby over to them instead of any other local babysitters because this is what their dad Kekrops looked like:

Kekrops was a “civilizing” figure who was credited with instituting the laws of marriage and property, the burial of the dead, and a new form of religious worship. He abolished human sacrifices, and invented writing. (Fast and dirty take? Sounds like a quick process of cultural change pinned onto a figure that represents a bridge between an older order and a new one that wanted to own the achievements of its sources of power: agriculture, patriarchal family relations, record-keeping, and the determination of what happens to souls after death.)

The girls’ self-destruction upon seeing a half-snake baby? Buncha snowflakes! Maybe they were ashamed of their own roots in the autochthonous pantheon — or perhaps Kekrops hadn’t entirely abolished human sacrifices.

Another key part of Kekrops’ mythos was he served as arbiter in the dispute between Athena and Poseidon over the possession of Attica, in which — we all know — Athena was victorious, thanks to her gift of the olive tree, which trumped Poseidon’s horses.

Athena frequently protected Erichthonius throughout his life. When he grew up, he drove a usurper off the throne of Athens, thus becoming its king and married a naiad, with whom he had a son. He was credited with establishing the Panathenaic Festival in Athena’s honor, and he installed a statue of her on the Acropolis. Erichthonius’ father Hephaestus was “lame,” and it was said that he was as well. Some legends style him as a culture hero who taught people how to yoke horses to pull chariots, which was an invention that aided his mobility. He also taught the arts of smelting silver and ploughing the earth. Zeus was so impressed with all of this that he installed him in the heavens as the constellation of the Charioteer after his death.

There is just one little wrinkle in all of this: Plutarch conflated the names Erechthonius and Erechtheus, and many contemporary sources still mix them up. Erechtheus was a mythical king of Athens, who conquered Eleusis. It is interesting that Erechtheus’ daughter (or daughters) were also said to have died unnaturally young: as sacrifices ordered by an oracle so that Athens would prevail over its rival city. This story is depicted on the east frieze of the Parthenon.

Here is a fantastic online gallery of primarily Archaic Gorgon art with great commentary. Happy browsing!

Speculatively, it is interesting to ponder the idea that Medusa was overcome through the use of a bright metal shield, which — perhaps — suggests the Bronze and Iron Age overcoming the powers of a previous era, which I discuss later in this essay.

A very clear parallel exists in Basque mythology.,which you can read about here:

”Outside the Aragonese town of Jaca, in the Pena Uruel mountain there lived a dragon that would hypnotise locals with his eyes, then devour them. After many travellers had been eaten, a brave young man from Jaca found the largest shield he could, and polished it so that it gleamed. He then took this shield and used it to reflect the stare of the dragon back to itself. Of course, the dragon became a victim of its own powers, and whilst stunned the young man killed it. Interestingly this parallels the Medusa myth, whose own serpentine hair possessed a hypnotic power, and the mythical basilisk (another reptile) has this talent (Amades, 1997).

In Lavedan, among the Davantaigues mountains, there exists a legend of a dragon that devoured people and oxen, and soon became the terror of the region. Eventually an enterprising young blacksmith decided to end the creature’s reign and took his tools up to near where the creature lived. He set up a forge and created a huge anvil, a quite enormous effort. He placed this anvil, glowing red hot, at the mouth of the cave where the dragon lived. Seeing the red object, the dragon became enraged and ate it, only to realise its mistake when its insides began to burn …”

Tatar discusses the injustice of the double standard for sexual behavior that left Poseidon free to pursue further adventures, and comments: “Is it perverse to think of her snaky appearance as a way of punishing the gaze of male predators, disabling them with her own deadly gaze?”

I don’t disagree with this perspective, but it’s also not a level I want to linger at any longer in my own analyses.

If you’re an etymology nerd and don’t want to accept this single lineage for Medusa’s name, I’m with you! Just wait, and I’ll provide a broader semantic range toward the end of the article.

I discussed the use of symbols in rulers’ self-legitimation at length in another post, “White Deer as Symbols of Worldly and Spiritual Power.”

White deer as symbols of worldy and spiritual power

Why deer? Why white ones? In The White Deer, I discuss the symbolism of the color white and of deer at length. There is no need to rehash all the details here, but the radiant gist is that for many reasons, whiteness is often associated with spiritual messages, as well as with danger and death.

Just don’t @ me with the folk etymology of Perseus = Persian, which is not accepted by today’s scholars. The hero’s name almost certainly descended into ancient Greek from Proto-Indo-European. Robert Graves suggested an etymology from the Greek verb πέρθειν (pérthein, "to waste, ravage, sack, destroy") some form of which is familiar in Homeric epithets. The philologist C. D. Buck points out that the -eus suffix typically creates agent nouns, so Pers-eus would be a "sacker [of cities] — a fitting name for the first Mycenaean warrior.”

The further origin of perth- is more obscure, but linguists point out that the PIE *bh- often descends to Greek as ph-. Thus, J. B. Hofmann lists the possible root as *bher-, which corresponds to "scrape,” or “cut." Nomen omen = perhaps he was born to chop heads!

Anna Lazarou and Ioannis Liritzis, “Gorgoneion and Gorgon-Medusa: A Critical Research Review” in Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology. The full text can be accessed here - click the link and you can download a PDF. As I mentioned in a footnote in Medusa I, their overview has been extremely valuable to me.

Through the ages there have also been countless Masters of Animals, and their omission here should not be interpreted as a denial of their existence. The reason I’m focusing on the Mistress is to connect her with Medusa, to the extent that this is tenable. I plan to discuss Masters of Animals in an article that should come out before the end of this year.

You know who could be considered an anti-Master of Animals? Heracles. His first amazing feat, which he accomplished as a newborn baby, was to strangle two serpents that Hera sent to attack him in his crib. He was found by his parents waving the dead reptiles around, as if in parody of the ancient figures.

Here’s Disney’s version of that scene:

When Heracles grew up, he killed or subdued quite a few of Echidna’s offspring. He also stole the cattle of Geryon, Medusa’s grandson (whose father was her son Chrysaor).

This doesn’t seem entirely coincidental, given his parentage: his mother Alcmene was a descendant of Perseus, and her father Electryon was the ruler of the city of Mycenae, which Perseus had founded. It’s almost like a family vendetta or something!

The British Museum has stated that its preference for identifying the icon with Ereshkigal is based on the wings not being outspread and the fact that the background of the relief was originally painted black.

If this were the correct identification, it would make the relief (and by implication the smaller plaques of nude, winged goddesses) the only known figurative representations of Ereshkigal. Edith Porada, the first to propose this identification, associates hanging wings with demons and then states: "If the suggested provenience of the Burney Relief at Nippur proves to be correct, the imposing demonic figure depicted on it may have to be identified with the female ruler of the dead or with some other major figure of the Old Babylonian pantheon which was occasionally associated with death" …

… E. von der Osten-Sacken describes evidence for a weakly developed but nevertheless existing cult for Ereshkigal; she cites aspects of similarity between the goddesses Ishtar and Ereshkigal from textual sources – for example they are called "sisters" in the myth of "Inanna's descent into the nether world" – and she finally explains the unique doubled rod-and-ring symbol in the following way: "Ereshkigal would be shown here at the peak of her power, when she had taken the divine symbols from her sister and perhaps also her identifying lions.

“Such use of the [cross] sign was not merely ornamental, but rather a symbol of consecration, especially in the case of objects pertaining to burial. In the proto-Etruscan cemetery of Golasecca every tomb has a vase with a cross engraved on it. True crosses of more or less artistic design have been found in Tiryns, at Mycenæ, in Crete, and on a fibula from Vulci." O. Marucchi, "Archæology of the Cross and Crucifix", Catholic Encyclopedia (1908).

The Egyptian cobra, often called an asp in literature, is the snake that allegedly participated in Cleopatra’s suicide.

Did any such thing happen?

Plutarch reported that Cleopatra tested a variety of poisons on convicted criminals and decided that death caused by cobra venom would be the least painful. Traditional sources say the predominant sensation is of sleepiness and heaviness, and death is caused by neurotoxins that block transmission of nerve impulses to the muscles, eventually leading to cardiac arrest and respiratory failure.

One wonders whether the subjective feelings of someone poisoned by cobra venom is that of being turned to stone.

Bullshit! calls professor Christoph Schaefer of Trier University, who confidently asserts “It is certain that there was no cobra."

Schaefer studied historic writings and consulted a toxicologist, after which he came up with an alternate theory. First, a cobra’s bite isn’t reliably fatal; second, despite what some have claimed in the past, death takes hours; there is local necrosis by the wound, and the victim suffers pain and paralysis of various parts of their body, including the eyes.

The Roman historian Cassius Dio, writing about 200 years after the queen died said Cleopatra’s death was quiet and pain-free, and other ancient texts mention that her two handmaids died along with her, which would have been hard to manage using snakes. Death by poison made a lot more sense, and it was recorded on papyri that Cleopatra herself had been testing and investigating them.

Schaefer and the toxicologist Dietrich Mebs believe the most likely cocktail contained hemlock, mixed with wolfsbane and opium, which would have produced a deadly slumber.

Herpetologists agree that the story of the “asp” is a myth rather than history. Why, then, did the tale persist for over two millennia? Mainly because of artistic representations, so it seemed to make sense that the snake — whose bite can be deadly — caused her death. However, he points out, many of the ancient depictions of Cleopatra — and other pharaohs — with cobras were intended to show her reception in the afterlife. Images of her holding an asp on her arm only appeared in the 15th century.

More of these wonderful images of syncretic snake deities can be found in this photo album on Flickr.

I discuss noa-names in a great deal of detail in my article “Speak of the Devil”. However, the case of the Bona Dea, it’s more like a code name that protects her true name and identity from non-initiates.

Speak of the Devil!

Lupus in fabula! Painting by Tokyo-based "naive" artist Kosuke Ajiro Lupus in fabula means “the wolf in the story" in Latin. It was taken from Terence's play Adelphoe and can be interpreted in context as "if you speak of the wolf, he appears.” It’s similar to the way that in English

Loved this! So thoroughly researched and theories well expressed

I too have often wondered about why the tongue sticking out, of course I instantly can draw comparisons to other cultures like the goddess Kali often portrayed with her tongue out, and in the Maori performance of the Haka the idea is to pull faces like sticking tongue out and bulging their eyes as a war cry before battle to intimidate their opponents but then your reference to it potentially mimicking the state of decomposition in death, and turning to stone like rigor mortis seems like a valid explanation as well, but what often confused me was the swastika symbol often also appearing alongside and like the Gorgon at Corfu, I forgot the name they give to that body position but it denotes running but also mimics the rotational movement of the swastika. I think Gimbutas has associated the swastika as one of the symbols of the womb, in terms of that regenerative quality like the turning of the wheel, of the seasons of life and death from womb to tomb. But there are two types of swastikas, the clockwise and the anticlockwise rotational versions. Another detail found in some gorgons was the snake belt, and I do feel there’s a connection there to fertility and birth, that the gorgon might have been remnants of a primordial goddess of both life and death, of midwife and death doula as snakes all around the world were often associated with childbirth, one being as a protective symbol, maybe connected to its resemblance to the umbilical cord, the serpent that needs to be slayed/ chopped off, before potentially strangles the baby as can sometimes happen in the womb, but also the snake girdle or snake belt appears to have been an aid in childbirth, to help ease the pain of childbirth when worn by the woman