1. Nemoralia: the Ides of August

The first in an interlinked series of three posts. This one focuses on the annual birthday party for Diana held at Lake Nemi

A contemporary tapestry depicting Diana and her dogs, woven the the Portuguese tapestry artist Renato Torres (2020).

Diana nemorensis

Diana, originally Jana,1 a pre-Roman goddess of the woods, animals, and hunting, has been Hellenized (assimilated) with the Greek Artemis and is often described as her “Roman equivalent.” However, they are not the same deity: Diana is an Italic goddess who is distinct in certain regards, such as her association with the moon. (Artemis was not originally a lunar goddess, and only became one through association with Diana.)

Diana has been worshipped both singly and in conjunction with other spiritw and deities, and, in addition to hunting, some of her other spheres of influence include healing and fertility, childbirth, and underworld mysteries.

Diana Nemorensis, by Max Nonnenbruch. Source.

One of Diana’s most important cult centers was at Aricia, a town located just to the side of the Via Appia between Lago Albano and Lago de Nemi (Lake Nemi). The area has beautiful woodlands, which made it attractive to wild animals, and therefore it was a very fitting place for the cult of a hunting goddess.

Archaeologists have uncovered ruins in the modern Italian commune of Ariccia that date the site back to at least the 8th–9th centuries BCE. In ancient times, the territory of Aricia, which was the central member of the Latin League for several centuries, once included Lake Nemi.

The name Nemi comes from nemus Aricinum (sacred grove of Aricia), but the Romans also had another name for the lake: Speculum Dianae – "Diana's Mirror." Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Lord Byron, and the French composer Charles Gounod had residences in Nemi, and, like the ancients, they commented on the way the moon was reflected at the center of the lake during the summer.

Diana’s Mirror, by Ralph Albert Blakelock (1880-1899).

The shores and hills around the Speculum Dianae remained popular among wealthier Romans over the ages for its lovely views, clean air and water, and a microclimate that created cooler temperatures in the summer. It is also known for its woodland flowers and sweet wild strawberries.

However, this wasn’t just an exurban getaway. On the northern shore of the lake was an ancient sanctuary. Originally, the facility must have been quite simple, consisting of a clearing in the woods2 enclosed by a wooden fence with an altar in the middle. A carved image of Diana triformis was the focus of worship on the site.

This marble Diana triformis statue is in the collection of the British Museum.3 It was taken from Rome, not Nemi.

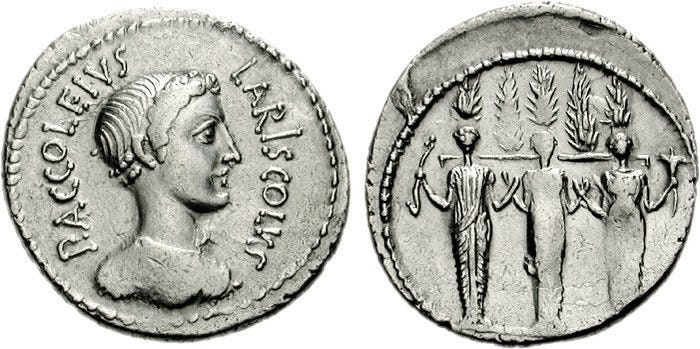

The coin shown below most likely depicts the head of Diana,4 with an image representing the statue of Diana nemorensis from three sides on the reverse. The triple Diana figures are supporting a beam that holds up five cypress trees.

Source: Wikimedia. This denarius is considered evidence that the triform statue remained in situ at least as late as 43 CE.

Below is a later Roman statue of Diana nemorensis, which is kept at the Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen:

Source: Wikimedia.

Around 300 BCE a new temple was built, and during the second century CE the sanctuary’s facilities were greatly expanded: “It was now arranged on a series of artificial terraces constructed entirely in Roman concrete as a means of creating a sacred architectural landscape.” A temple constructed in an unusual and ingenius style was built and other buildings were added, including baths, a theater, shrines to other deities, and a nymphaeum, as well as a dwelling for priests and accommodation for pilgrims. It was one of the largest and richest sanctuaries in all of Italy, and a place where political alliances were forged and renewed.

Sadly, after centuries of vandalism, looting, and neglect, only ruins are left at the site today, and they are very badly overgrown.

Adam Nathaniel Furman made this reconstruction of the temple of Diana at Nemi, as it looked in 300 CE.

The Nemoralia — women’s rites at a lakeside retreat

The first thing that comes to most people’s minds when Nemi is mentioned is the violent succession of the Rex nemorensis made famous by J.G. Frazer in The Golden Bough. I’ll discuss Frazer and all the rest of it in Part 2 (a separate article). For now, let us focus on something more timely: the Nemoralia.

Men and women, and people from all social classes were welcome to visit the sanctuary and temple at Nemi and pray or ask for practical guidance on hunting or childbirth. However, the festival of Nemoralia was reserved only for women — and their dogs. It was originally celebrated on the Ides of August (the 13th-15th of the month in the city of Rome), and it was also called the Hekatean Ides5 or the Festival of Torches. The celebrations eventually became so popular that they spread from Lake Nemi to many other parts of Italy, with the alternative that in more rural locations the festivities were sometimes held at the time of the August full moon instead of on the Ides. (If you are planning to celebrate, you might try it either way.)

Now that’s some Sirius heat!

The rites were taking place just on or after the culmination of the “dog days” that ended around August 11. This period of forty days was named after the ancient Greeks’ observation that Sirius, the brightest star in Canis major and the namesake of Orion’s hunting dog, was rising alongside the sun. They believed the star added heat, and even its Greek name, Σείριος, means “hot” or “scorcher.”

We have all observed that the effect of the year’s hottest weather on actual dogs are usually stupefying: they loll, pant, and sploot on cold tilesor try to refresh themselves in any water available instead of getting into mischief.

A splooting corgi.

However, old Greek traditions and Hellenistic astrology associated the “dog days” not only with hot weather, but also with bad luck, drought, epidemic fevers, wars, and other disasters. These are a few of Homer’s lines from the Iliad:

On summer nights, star of stars,

Orion's Dog they call it, brightest

Of all, but an evil portent, bringing heat

And fevers to suffering humanity.

Achilles' bronze gleamed like this as he ran

In Works and Days, Hesiod wrote:

But when the artichoke flowers, and the chirping grass-hopper sits in a tree and pours down his shrill song continually from under his wings in the season of wearisome heat, then goats are plumpest and wine sweetest; women are most wanton, but men are feeblest.

Sounds like a perfect time for the Roman women and their favorite dogs to leave the men behind and take an excursion outside the city!

The poet Statius wrote in the 1st century CE:

It is the season when the most scorching region of the heavens takes over the land and the keen dog-star Sirius, so often struck by Hyperion's sun, burns the gasping fields. Now is the day when [Diana] Trivia's Arician grove, convenient for fugitive kings, grows smoky, and the lake, having guilty knowledge of Hippolytus, glitters with the reflection of a multitude of torches; Diana herself garlands the deserving hunting dogs and polishes the arrowheads and allows the wild animals to go in safety, and at virtuous hearths all Italy celebrates the Hecatean Ides.

The Nemoralia seems to be a rite of great antiquity. The poet Ovid said this rite was “held sacred by a religion from the olden times.” How old? Some scholars claim that the festival itself predates the spread of the cult of Diana, and the sacred grove and its rites may date to as early as the 6th century BCE.

The purpose that brought worshippers together was throwing a birthday party for Diana. Pilgrims prepared themselves beforehand by bathing and decorating their hair with flowers. Dogs — as one of Diana’s sacred animals — were also honored, and they, too, were decorated with flowers. Although she was the goddess of the hunt, hunting or the killing of any beast was forbidden during the Nemoralia, so naturally all dogs, just like the women and the slaves, were enjoying a holiday. On these days slaves were relieved of their duties on this day and when slaveholders participated they were set on equal terms with the other women, because the day was for Diana, not for them.

The Nemoralia was referred to as the Festival of Torches because women walked in a procession lit by torches and the moon to the sacred grove, carrying their wreaths and garlands, fruit, and cakes. When they arrived, they wrote prayers and requests on ribbons and tied them onto trees.6 Then when the procession reached the grove, they they placed their offerings on Diana’s altar. The festive foods were ringed by a circle of white candles so they would glow like the moon.

Effigies made from bread or clay that were shaped like body parts that women wanted healed were also set out for the goddess to bless. Pilgrims didn’t have to be handy with shaping clay or have access to a kiln — these products could be purchased at stalls there on the site.

Clay womb, eye, ear, breast, and internal organs. Source: Rachel A. Diana at Mount Holyoke.

More clay votive offerings displayed at the museum in Nemi, photographed and published in the My Castelli Romani blog.

Would you also like to honor Diana?

Writing this series of blog articles and celebrating the Nemoralia last year must have opened up a portal for me. Last fall, I discovered the Diana - The Lake and Her Mysteries course at the Bosco di Artemisia academy. And this summer, I partook of live seminars she led, and then had an opportunity to spend four days in Nemi. I wrote this article before encountering the much deeper knowledge archaeologist Giulia Turolla provides for her students. It wouldn’t be right to share that material here, but I heartily encourage all who wish to get to know Diana more deeply to take this course — and to celebrate the Nemoralia.

Here are a few suggestions for celebrating Diana’s birthday:

Put something festive on yourself and on your dog so you look nice, and bake a cake. Here, you can find Gather Victoria's7 recipe for an apple and pear cake fitting for the Queen of the Wildlands. You can make a large one to share with your friends and your dog and a small one to dedicate to Diana. However, don’t use the Queen Anne’s Lace if you’re giving any of the cake to a dog. You night even find a recipe for a dog cake that’s tastier for them and more healthy than cakes made for people.

Sorita d’Este’s article provides a template for a ritual that one might perform either alone or with others. Preparations are required beforehand, so make sure you have everything you need. She suggests offering two devotional verses to Diana. One on her page was penned by Ben Johnston. Another good choice would be the Orphic hymn to Diana, or, of course, a poem or chant you compose yourself.

A lake or another body of fresh water (stream, spring, pond) would be an excellent place to make your encounter with Diana. It would be very appropriate to also offer something to her: I made a vow to clean up trash on wooded paths and lakesides, and I put particular efforts into this around Lake Nemi.

Sometimes, we see the misinformation that the ceramic body parts were “offerings” to Diana. They weren’t — the effigies were used in petitions for healing. In any case, poetry, incense or candles (if you bring everything you brought back home with you, including tealight bases, etc.), poetry, and vows make excellent offerings and do not junk up sacred sites with litter, ribbons on trees, etc.

Bold of them to make this Assumption …

Diana’s rites were, of course, suppressed by the Christians, and August 15th was turned into the Feast of The Assumption of Virgin Mary. Sometimes even today grains are brought to churches for blessing upon this holiday, which marks an interesting syncretism, because if Frazer was right that the masculine cult at Nemi had something to do with a rising/falling and sacrificed god, and the cult of Diana seemed to have much more archaic roots, we see the Church actively packaging them both together.

Mary is quite a different figure than Diana, and the fest of the Assumption celebrates the day she ended her mortal life and was dispatched bodily into Heaven. The tradition dates back to the fifth century CE or so, but it was not defined by the Catholic Church until 1950, when Pope Pius XII issued an infallible statement that officially defined the dogma of the Assumption:

By the authority of our Lord Jesus Christ, of the Blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and by our own authority, we pronounce, declare, and define it to be a divinely revealed dogma: that the Immaculate Mother of God, the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.

Like Mary, Diana was also a “ virgin,” a term vexed with shifting definitions over the ages.

In Diana’s case, it primarily meant that she was single, free, unwed,8 and not a mother. To the extent that her chastity was emphasized, it may have reflected ancient taboos on engaging in sexual intercourse before going out on a hunt. Let’s recall the myth that tells what she did to horndog hunter Actaeon.

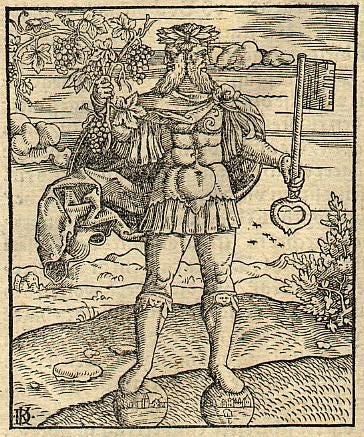

Image of Actaeon from Andrea Alciato's Emblemata (1551), published online in digital facsimiles by Alciato at Glasgow.

So, while Artemis/Diana was known for dealing harshly with suitors and peeping toms, her chastity was not absolute: she had a love affair with the giant hunter Orion.9

The Latin virgo probably arose by analogy from the word vireo, meaning "to be green, fresh or flourishing" — in a botanical sense.10 And this is interesting because it recoups the idea of potential fertility rather than austere sterility. Diana/Artemis is associated with midwifery and childbirth, which strikes some moderns as odd since she isn’t a mother herself. However, as her mother Leto’s firstborn, she helped deliver her twin brother Apollo. Her “wild” and “uncivilized” nature also corresponded to the liminal time of childbirth, when, the Classical tradition said, women are farthest from culture and closest to nature.

On the other hand, while she could heal and nurture, she could also bring disease and kill.

Her brother Apollo, too, played contradictory roles:

Apollo, Sending out Plague Arrows by Alexander Rothaug, ca 1920.

In modern, simplified understandings, Apollo is often characterized as a god of music, the sun/light, and healing. But the ancients told that also sent plagues, which he spread by shooting his deadly arrows. Sometimes he just used the arrows to kill directly, and so did Diana: usually, Apollo’s golden arrows were shot at men and boys, and Diana’s silver ones were shot at girls and women. This, naturally, hints at these deities’ ancient roles as psychopomps.

In the tragic story of Niobe and her children, Apollo and Artemis slay the boastful queen’s seven sons and seven daughters to teach her — and other mortals — a lesson.

Apollo and Diana attacking the Children of Niobe, by Jacques-Louis David, 1772. Wikimedia.

Myths are contradictory, like dreams, and you never get to the bottom of what they “really mean.” But reflecting on them and using the stories is part of living a full and good life; one that is big enough to contain contradictions and mysteries and has space for wonder.

Living into relationship with one’s symbols is not for the impatient, but a slow process of becoming trustworthy. One is never certain with a dream, never at the bottom of it. At best, you grow increasingly tolerant of ambiguity, ever-humbled by the grace of divine instruction, ever-renewed in your heart’s rapture at being a novice. Paradoxically, it is in your capitulation to the mystery that mastery is cultivated.

-Toko-Pa

Wishing happy dog days to all!

(I have been unable to source this wonderful image, which is widely shared on Pinterest.)

What’s coming up next:

As I indicated in the subheading at the top of the page, this is Part 1 in a 3-part series. Now that we know what women were up to at Nemi, we’ll proceed to take a look at the ancient stories of the Rex nemorensis, at the early anthropologist J. G. Frazer who popularized the legends in his Golden Bough, and at one of Frazer’s famous critics who was willing to throw down to defend his right to be considered the king of philosophy at Cambridge University.

Part 2, "The king is dead - long live the King!" is now up.

The third part will focus on the enigmatic motif of the Corn Wolf, and I hope to have it finished in a week or so.

In addition, I have submitted a long article titled “Ring of Bones” to the editors at A Beautiful Resistance. Keep your eyes open for a Note from me announcing its publication.

Please subscribe!

I put a lot of time and care into creating these posts, lovingly, by hand, in my kitchen or in the shade of a wide-spreading walnut tree. Each article I write takes at least several days of hard work; no chatbot technology is used whatsoever, nor am I compensated financially. Please consider subscribing, because subscriptions give me an idea of how many people enjoy reading my work, or whether this is just a solitary hobby. Sharing the posts online or with friends via email will also expand its reach.

If you like the articles, I’m sure you will love my book The White Deer: Ecospirituality and the Mythic, which is on sale from the publisher now at a 25% discount.

According to Mythopedia, Diana’s name stems from the Proto Indo-European *dyeu, meaning “to shine,” as well as “sky,” “heaven,” and “god.” We can see similar forms derived from this root in the Greek theos, the Latin deus, and the Sanskrit deva. Other derivatives were the Latin word dies, meaning “day,” and diurnal, meaning "daylight," but Diana is more associated with the moon and nighttime. The apparent paradox is resolved in her title of Diana Lucifera ("light-bearer"), derived from dies, the light of the moon.

In any case, this etymology helps us push her history back to at least the first millennium BCE, if not earlier.

” ... people regard Diana and the moon as one and the same. ... the moon (luna) is so called from the verb to shine (lucere). Lucina is identified with it, which is why in our country they invoke Juno Lucina in childbirth, just as the Greeks call on Diana the Light-bearer. Diana also has the name Omnivaga ("wandering everywhere"), not because of her hunting but because she is numbered as one of the seven planets; her name Diana derives from the fact that she turns darkness into daylight (dies). She is invoked at childbirth because children are born occasionally after seven, or usually after nine, lunar revolutions ... “

— Quintus Lucilius Balbus, quoted by Cicero in De Natura Deorum [On the Nature of the Gods].

A friend who read the article asked if the names John/Jan/Jane/Jana are related to Jana, and I told him they aren’t. These names are derived from the Hebrew Yohanan, which means “YHWH is gracious,” and YHWH has an entirely different origin.

Janus, the two-faced Roman god, is also not related. Macrobius (early 5th c. CE) suggested that Ianus (Janus) was a composite of Apollo and Diana (Iana) who represented the sun and moon — because, in his Saturnalia, he attempted to explain all forms of worship as reverence for the Sun. J. G. Frazer accepted this theory in the 19th century, but more recent, and more careful philology reveals that there was no such lineage or association.

Janus, the Roman God, by Sebastian Münster 1550. Wikimedia.

However, janas, a kind of Sardinian fairy, are related, as testified by Wiktionary.

In Latin it was a lucus: “The term lucus had originally applied to trees or a patch of woodland, but evolved rapidly to mean an open space surrounded by woodland, more like a landscaped park, with features used for ritual such as wells or springs and a shrine containing the image of a god. The largest examples might contain a temple or even buildings housing a market. The Roman sacred groves were often found on the edge of cities amidst fully cultivated land, and performed several functions, including as places for meetings or assemblies.”

According to Bouke: ‘After an initial stage of being a sacred glade, clearing or grove where votive gifts could be deposited, a lucus could be monumentalized by the addition of altars, statue bases, votive cippi (i.e. short pillars with inscriptions) and temples.’

The curator notes: “Diana as a threefold deity first appears in the late republic and represents as a new visual type in Italy, in which the figure of Diana the huntress is unified with her appearance as Selene the moon goddess and as Hekate, goddess of the Underworld. The statue type of the three goddesses joined to a pillar with their heads facing in three different directions was one of the earliest images erected by Alkamenes in Athens, on the bastion of the temple of Athena Nike, in c. 425 B.C.”

If she’s not Diana, the other possibility is Acca Larentia, another ancient Italian goddess/legendary figure associated with the founding of Rome.

Hekate has often been assimilated with Diana, via conflations with Selene and Artemis that are attested in the Greek Magical Papyri. As you can read on the pages kept by the Covenant of Hekate: she is also associated with dominion over liminal spaces and with the Cosmic Soul. “Plutarch saw the moon as an intermediary and transmitter between the Sensible and Intelligible worlds, which was a function of the Cosmic Soul (psyche) for the Neoplatonists. The moon was seen as a place of spirits, souls and daimons and had a similar role to the realms of the Underworld. Hekate previously had significant chthonic attributes and symbolism attached to her and when the moon was seen as a resting place of spirits (like the underworld), it was logical that a goddess who was strongly associated to this theme became connected to the moon as well.”

The same page also provides Porphyry’s description of Hekate as a lunar from his work on idols:

“But, again, the moon is Hecate, the symbol of her varying phases and of her power dependent on the phases. Wherefore her power appears in three forms, having as symbol of the new moon the figure in the white robe and golden sandals, and torches lighted: the basket, which she bears when she has mounted high, is the symbol of the cultivation of the crops, which she makes to grow up according to the increase of her light: and again the symbol of the full moon is the Goddess of the brazen sandals. Or even from he branch of olive one might infer her fiery nature, and from the poppy her productiveness, and the multitude of the souls who find an abode in her as in a city, for the poppy is an emblem of a city. She bears a bow, like Artemis, because of the sharpness of the pangs of labour. And, again, the Fates are referred to her powers, Clotho to the generative, and Lachesis to the nutritive, and Atropos to the inexorable will of the deity.

Also, the productive power of the corn crops, which is Demeter, they associate with her, as the producing power in her. The moon is also a supporter of Kore. They set Dionysus also beside her, both on account of their growth of horns, and because of the region of clouds lying beneath the lower world. … Aristophanes who “recorded that offerings to Hekate were made “on the eve of the New Moon” that is when the first sliver of the New Moon is visible. This chapter also refers to K.F. Smith’s essay mentioning “a possible connection with Hekate as a lunar goddess, rising like the moon, from the underworld on the night of the New Moon.” Here we have two references to the New Moon being the first visible fragment of the moon’s form.”

Please don’t do this! “Clooties” are harmful to trees and wildlife. Even though the practice is ancient indeed, modern Pagans should think of ecology first and respect the spaces they visit. For more, see the Cleaner Clootie Campaign.

Gather Victoria is a Patreon project devoted to sensual appreciation of the land and its seasons, food, history, and mythology. It is, at present, the only Patreon project I support, and I can’t possibly praise it highly enough or recommend it enough to the types of people who are into the same kinds of things as I am. Here is Danielle’ Prohom Olson’s website where you can find out more, including recipes she shares with the public.

Well, she’s usually unwed. There are some isolated traditions that make Artemis the wife rather than the sister of Apollo. Exception proves the rule?

But, no matter which version of the story you read, it always ends with Orion dead. He is put in the sky with Sirius, his favorite dog. See the collection of myths here, and contemplate the connection between the dog days and the Nemoralia once more in this connection.

Here is much more discussion of the matter. I don’t give any credence to etymologies such as vir (strength, virtue, power) + gyne (woman), which seem to be of recent, wishful provenance. Unfortunately, these folk etymologies proliferate online because they appeal to modern sensibilities.