2. The king is dead - long live the King!

This is the second part of a triptych of posts. Here, I focus on the Rex nemorensis, a re-reckoning with J.G. Frazer's legacy, and on a pitched battle for the title of King of Philosophy at Cambridge.

The Rex nemorensis

In my most recent article, “Nemoralia: the Ides of August,” I discussed the rites held at Diana’s sacred grove to celebrate her birthday.

The arrow in this photograph, which I sourced from the Penn Museum blog, shows the location of Diana’s sanctuary. The Speculum Dianae (lake) is on the right side.

Swiss symbolist Arnold Böcklin’s The Sacred Grove (1882).

However, after the worship of Diana was suppressed and the Nemoralia was replaced with celebrations of the Assumption of Virgin Mary, another legacy from the sacred grove of Nemi became far better known.

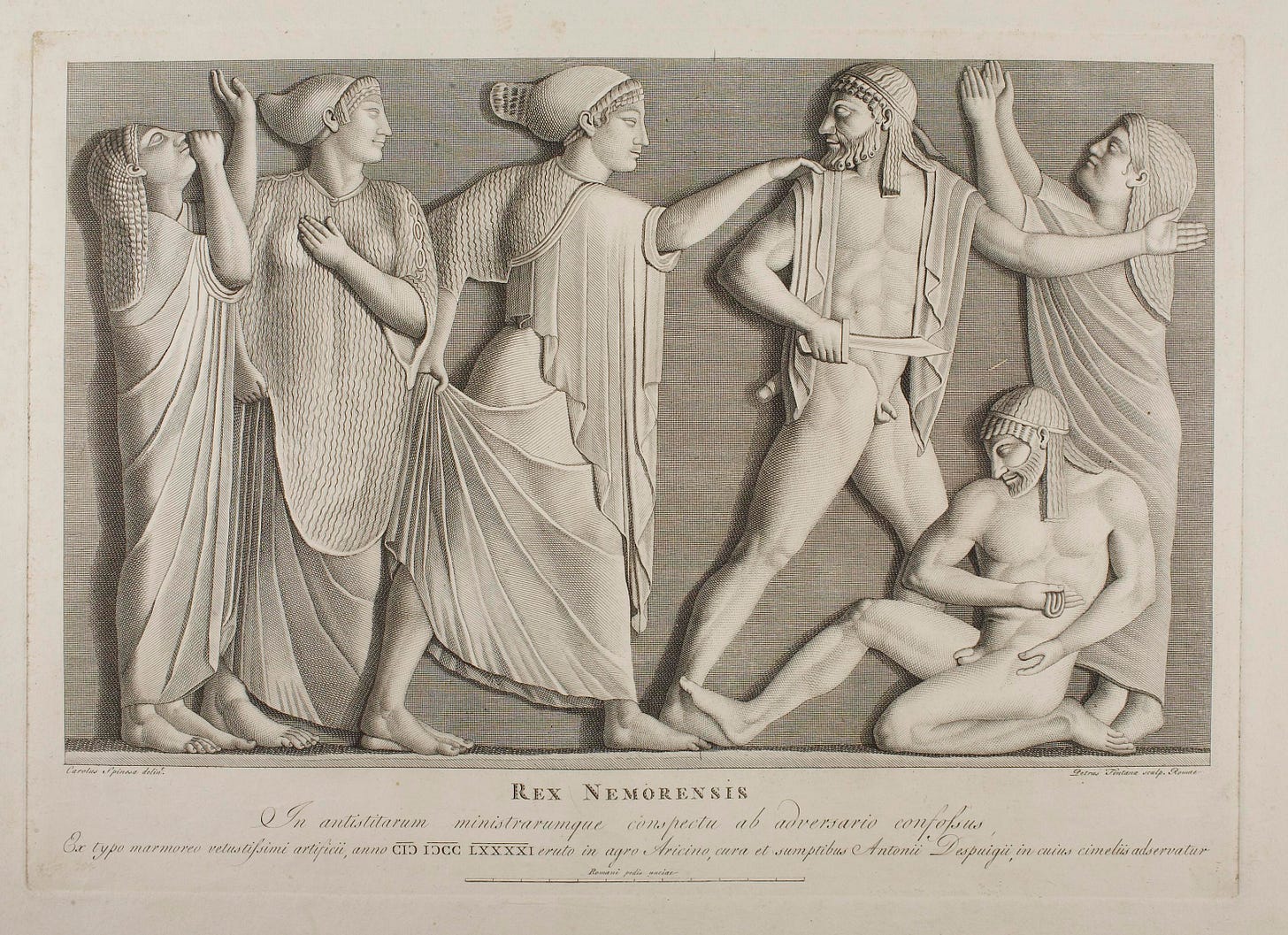

Rex Nemorensis, a copper engraving by Pietro Fontana (pre-1837).

The Rex nemorensis was the priest of the temple of Diana at Nemi who enjoyed the sole right to bear arms there. It is not known exactly what his religious duties were, but he ruled over a small band of men living in the woods around the grove. According to Strabo, Diana’s priest had to be a fugitive slave, and many have assumed that the most or perhaps all of the rest of the grove’s permanent inhabitants were also outlaws.

The classical literary tradition held that each of these “kings” was succeeded by the first man who overcome him in a single-combat duel. Ovid tells us:

“one with strong hands and swift feet rules there, and each is later killed, as he himself killed before.”

In order to challenge the reigning king, the newcomer had to break a golden bough off one of the trees, and then the fight was on — to the death.

Strabo, cited here, describes the setting and the scenario, which he and his contemporaries considered exotic:

“... to the left of the way as you go up from Aricia, lies the Artemisium, which they call Nemus. The temple of the Arician [Artemis], they say, is a copy (άφίδρυμα) of the Tauropolos. And in fact a barbaric, and Scythian, element predominates in the sacred usages, for the people set up as priest merely a run-away slave who has slain with his own hand the man previously consecrated to that office; accordingly the priest is always armed with a sword, looking around for the attacks, and ready to defend himself.”

Numerous ancient authors, including Suetonius, Pausanias, and Servius, also wrote about these priests and their bloody rites of succession. Analysis of the literary sources suggests there was some kind of living tradition rooted at least as far back as the early Imperial period, and they regarded the brutal killings as elements of an imported cult. “This fierce goddess [the Taurean or Scythian Artemis Tauropolos], whose sanctuary was located in the Crimea, demanded human sacrifices. It is probable that the Romans applied the myth of Artemis Tauropolos to the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis to explain an otherwise inexplicable bloody ritual in that Sanctuary“ (i.e., the ritual killing of the Rex nemorensis).

Modern scholars quibble and pore over the details of when various elements were introduced to the legend, where they came from, and what, if any factual bases could support the interpretations, but I’ll leave them to their areas of specialty because I want to move on …

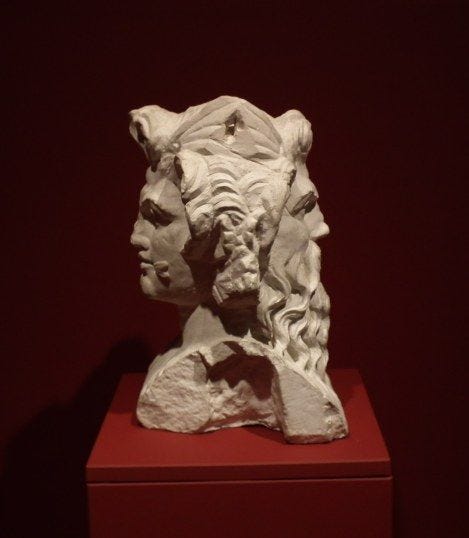

This double-headed herm possibly depicts the Rex nemorensis. I sourced this image from the Nemi to Nottingham blog, which has a lot of good writing on the subject of the Rex nemorensis, including a succinct summary of the legend and some of the major literary sources.

Let’s take a brief moment to contemplate how the story of the Rex nemorensis echoes another myth related to Diana: Actaeon, the hunter who himself became prey.

Actaeon being changed into a stag painted on maiolica, possibly by the master F.R. Urbino (ca 1525-30).

Frazer’s dying/rising god

James George Frazer, sketched by Matt Soffe — one of the artist’s “10-minute potraits.”

In his monumental multi-volume work The Golden Bough,1 which was first published in 1890, the Scottish anthropologist and folklorist Sir James George Frazer attempted to prove that humanity everywhere undergoes the same trajectory of intellectual development. His scheme was not unlike other period concepts that proposed that social organization progressed from stages of “savagery” to “barbarism” and finally “civilization,” but the focus was on cultural understanding of causality.

Frazer constructed his theory around the legend of the Rex nemorensis. Here’s how he retold the story:

In the sacred grove there grew a certain tree around which at any time of the day, probably far into the night, a grim figure might be seen to prowl. In his hand he carried a drawn sword, and he kept peering warily about him as if at every instant he expected to be set upon by an enemy. He was a priest and a murderer; and the man for whom he looked was sooner or later to murder him and hold the priesthood in his stead.

He claimed that this same story, of a sacrificial, sacred “king” who must be ritually slaughtered by his successor, was the magical origin of all religions. He believed it reflected a natural association between the vegetative cycle (particularly of grain crops) and human leadership.

Frazer drew the distinction between magic and religion thus: “whereas magic aims at controlling nature directly, religion aims at controlling it indirectly through the mediation of a powerful supernatural being or beings to whom man appeals for help and protection," but this understanding that there was a unilinear progression from sympathetic magic to religion to science is both sloppy and easily falsifiable.

Additionally, he characterized savage societies by their conflation of the roles of priests and kings, and of men and gods. In Frazer’s words:

Kings were revered, in many cases not merely as priests, that is, as intercessors between man and god, but as themselves gods, able to bestow upon their subjects and worshippers those blessings which are commonly supposed to be beyond the reach of mortals, and are sought, if at all, only by prayer and sacrifice offered to superhuman and invisible beings. Thus kings are often expected to give rain and sunshine in due season, to make the crops grow, and so on.

Frazer believed that societies eventually arrived at a scientific worldview, which would cause traditional beliefs to evaporate under rational scrutiny.2 This conception was not unlike some of those put forward by August Comte, a philosopher and one of the founders of the discipline of sociology, whose work preceded Frazer’s and still remained influential in his time.3

Modern scholarship has no use for such universal archetypes, or for schemes of cultural evolution. However, the biggest problem with these kinds of evolutionary timelines is the way they have been put to the service of violent colonialism and missionary misadventures around the world. The destruction and terror they cause is ongoing, not only from historical crimes against humanity but from new forms of exploitation that could hardly have been imagined in Frazer’s time.

Civilization — From Cape to Cairo. Illustration by Joseph Keppler from the American satirical Magazine Puck. February 12, 1902.

Frazer’s impact

When it was first published, The Golden Bough was treated as a dangerous (or at least scandalous) heresy, because it regarded the Christian story of the dying/rising Jesus4 as just one more iteration of an ancient theme that represented an intermediate step between “primitive” belief in magic and a fully-evolved scientific worldview. Bowing to pressure, the third edition of the work put his discussion of Christ into a speculative appendix, and it was excluded altogether from a later abridged version of the work.

This reaction was based in period authorities’ desire for the stories and rites of Christianity to be uniquely valid and true and also entirely separate from any “myths” or “primitive” or “savage” practices. However, Frazer wasn’t wrong about similarities between some of the figures — he was only wrong to extrapolate them to the entire world. The dying/rising god he describes has mostly been found in the ancient Near East and the Greco-Roman world, where it is a distinctive and persistent mytheme. (Other male examples besides Jesus include Tammuz, Osiris, Dionysus, and female examples include Ishtar and Persephone.) So there is a certain validity to comparative analysis of regional variants of the myth, but not to its universalization.

Frazer’s oeuvre ended up being more influential in the arts than in anthropology, but the thrust of his general argument did become part of mainstream western thought in the twentieth century. This was not so much the case in academic milieux, where most scholars were becoming particularists instead of generalists, and where “grand narratives” were increasingly treated with skepticism; rather, echoes of his ideas lingered in places like school textbooks and the mass media, where words like “progress” and “civilization” could be used without blushing. Even now this proposition is still taken as common sense by many, and is, indeed, part of the contemporary “conservative” worldview.

Frazer’s critics

Frazer didn’t make up the story of the Rex nemorensis: it has been attested by a number of ancient writers. However, standards for citation varied widely in the ancient world, and in his time, just as they do today:

Frazer played fast and loose with his sources, as I will discuss below, and the eminent British social anthropologist Edmund Leach spoke for many of Frazer’s critics when he wrote: "Frazer used his ethnographic evidence, which he culled from here there and everywhere, to illustrate propositions which he had arrived at in advance by a priori reasoning, but, to a degree which is often quite startling, whenever the evidence did not fit he simply altered the evidence!”

It should also be noted that no archaeological evidence has ever been discovered during the ongoing excavations at Nemi that would substantiate the old legends.

J.G. Frazer, Herbert Spencer, and E.B. Tylor are considered three of the paramount examples of armchair anthropology; a discarded model where scholars who have never visited or observed the people they write about feel free to theorize about them. When Frazer was asked why he never went out to meet any of the “savages” he wrote about he allegedly replied: "Heaven forbid!" These are some of the reasons why, despite the enduring popularity of his work in the arts, he has been considered an embarrassment by anthropologists.

Part of the problem with armchair anthropology was that much of these theorists’ information was gathered by missionaries and colonists who aimed to prove that the people they had observed were in great need of further “civilizing” efforts. In order to drum up sympathy and material support, they often distorted their reports to make them more sensationalistic. Twentieth-century academic anthropology wanted nothing to do with such disreputable practices or, usually, with church-funded missions. The discipline’s standard practices for gathering evidence shifted during the first half of the twentieth century toward fieldwork and participant-observation. Moreover, on the last fifty years there has been an increasing emphasis on attempting to safeguard the well-being of the populations studied rather than leaving them more vulnerable to exploitation.

Among anthropologists it is now expected that others’ worldviews will be taken seriously. Any phenomenon that might be possible to isolate or name should be understood as part of a cultural matrix that produces complex, overlapping webs of meaning that make sense and not just as data to be cherry-picked. And humility is a virtue: cultural observers are taught not to fall into a trap of believing that the “other” is the same as us, but just sadly missing a few important bits and pieces. “Narcissus is the old god of anthropology, for his habit of looking at the other as a reflection that lacks being. The other lacks reason, history, writing — something.”5 Thus was the anthropological approach of Frazer’s time. Today, we know better; we try to do better, and we ask for feedback.

A particularly obsessed critic

I made this meme — you’re welcome :-) . Wittgenstein’s quote is taken from the conclusion of his Tractatus.

Probably Frazer’s most obsessed, persistent, vitriolic, and also secretive critic was the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. As David Graeber recounts,

“Ludwig Wittgenstein became fascinated with Frazer’s Golden Bough in 1930. His intellectual biographers consider it a key turning point in the path that lead him from the positivism of the Tractatus to his later work on language games; he originally intended to use his comments on Frazer as an introduction to his Philosophical Investigations, but later changed his mind. In the end he never managed to turn them into a publishable work, but just kept periodically reworking them for the rest of his life.

The material he encountered in The Golden Bough confounded his attempts to reconcile it to any logical system, just as the potlatch ritual would later confound Jean-Paul Sartre, and cause him to abandon attempts at creating a system of ethics (Graeber). Wittgenstein continually accuses of Frazer of stupidity, and he was clearly infuriated when he wrote: “Frazer is far more savage6 than most of his savages, for these savages will not be as far removed from an understanding of spiritual matters as an Englishman of the twentieth century.”

It is the elegance of a unity composed of a dizzying diversity that makes Frazer’s work so compelling to artists and among those who dare to create rituals themselves. Because “no work of contemporary anthropology really offers such a detailed of grammar of possible ritual gestures (asperging in water, passing over fire, invoking, evoking, exorcising, setting apart, mimicking, destroying ... )” it’s possible to mix and match and tailor a rite to order, which has been very liberating. The idea that there is an ancient and universal template provides myth-makers and ritualists with assurance that it’s hard to truly go wrong, and anything based upon a “universal” myth gives the impression of a greater depth and power. Plus, it becomes possible to subvert the dominant Christian/monotheist paradigm, which had become so wearisome, either by embracing “primitive” templates or by psychologizing them as archetypes.

Frazer was a better prose stylist than many academic writers, and he bequeathed us a library, a grammar and vocabulary, and endless leads that we could later use when we went out seeking better information. Those pursuing poetry and story and not verified facts and plausible interpretations have an nearly bottomless wellsping in his work.

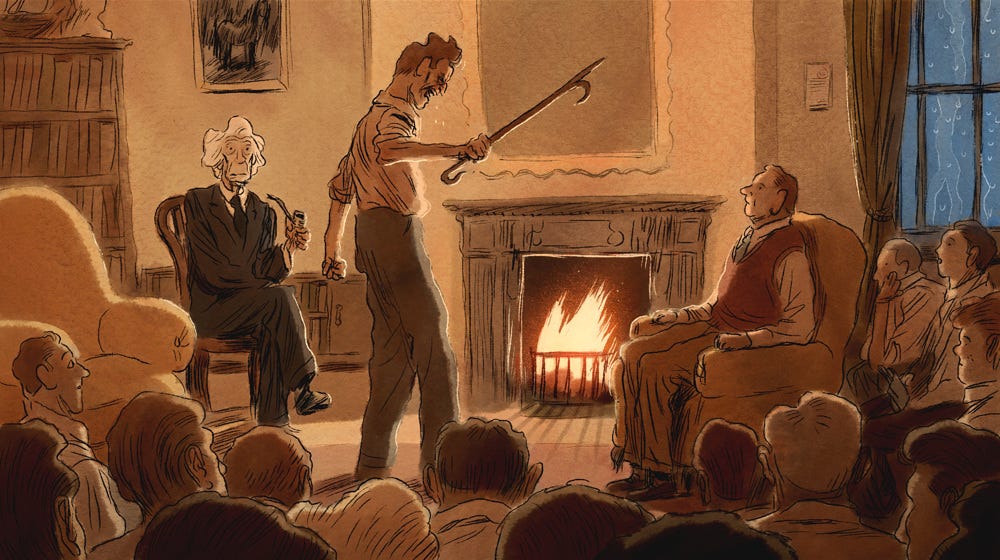

Wittgenstein’s poker: the reigning king defends himself against a challenger

Picture this: a meeting of Cambridge University’s Moral Science Club in a small, dusty, crowded room on the evening of Oct. 25, 1946. There is no central heating, but there is a lively blaze in the fireplace. Ludwig Wittgenstein was presiding over the meeting, and the Club had invited Karl Popper to address the question ''Are there philosophical problems?'' In attendance were other notable scholars, including Bertrand Russell. This detailed book review describes the scene in detail: it was the only time these three men would be at the same place together.

Enter the room, if you dare, and take a seat: Popper begins speaking, but after only thirty seconds had passed, Wittgenstein rudely interrupts and begins heckling him. Tension rises. Popper responds to the questions without giving in to emotions, but Wittgenstein becomes increasingly agitated. According one observer, “Wittgenstein is not reducing the guest to silence (the impact he is accustomed to), nor the guest silencing him (ditto).” Wittgenstein had been playing with a red hot poker, then all at once pulls it out of the fire and angrily gesticulates with it in front of Popper’s face. Bertrand Russell spoke up, saying “Wittgenstein, put down that poker at once!” Popper, whom Wittgenstein had challenged to provide an example of a universally valid moral rule, said “Thou shalt not threaten a visiting lecturer with a poker.” In a rage, Wittgenstein threw the poker down; then, after an awkward moment passed, he stormed out of the room, slamming the door behind him.

As was the case with the Rex nemorensis and his challengers, these two men’s desire to fight was mutual: Popper had, in fact, shown up that day hoping for a confrontation with Wittgenstein, though he probably didn’t expect it to go down quite like this. He later wrote: “I admit that I went to Cambridge hoping to provoke Wittgenstein … and to fight him on this issue.”7

Finally, another key similarity between the two Austrian philosophers and the dueling kings at Nemi is that they were fugitives. Both Popper and Wittgenstein were ethnically Jewish and had fled the Third Reich. In addition, three out of four of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s older brothers had died by suicide, and the themes of succession and of suicide were often on his mind. The "conspicuous courage" he displayed at the front in the First World War may have also been related to desires to hasten his death and to go down fighting.

Illustration by Mikkel Sommer for Wittgenstein’s Poker, by David Edmonds and John Eidinow. The video, which is based on these men’s book by the same name, presents the major points from the book and then shows a Q&A session with readers and listeners who attended a live event.

The video itself is linked below:

Reevaluating Frazer today

Several books have been published recently that reevaluate the Wittgenstein vs Frazer controversy — it’s a question that seems to be animating anthropological discourse again because it touches upon issues vital to the discipline’s self-conception.

Here, you can access and download a PDF of David Graeber's "Remarks on Wittgenstein's Remarks on Frazer," which he made available on his (posthumously managed) page and is well worth reading.

Cheers, Dave! Let’s all raise the next glass or mug we drink out of and toast the memory and legacy of David Graeber, co-author of the essential The Dawn of Everything.

Graeber points out the fact that Frazer cannot be ignored by anthropologists who want to look at how anthropology has functioned outside the academy — for over a century and a quarter:

In a way this just exemplifies everything that makes Frazer such an irritant for the discipline: for all that he embodies everything the discipline has rejected, he is still, to this day, the world’s most influential anthropologist. The Golden Bough has remained continually in print for 120 years, and continues to sell thousands of copies in dozens of languages across the world each year; it has inspired some of the greatest works of 20th century literature, and still inspires poets, novelists, artists, and filmmakers … present it all in a tone of deeply sensuous appreciation that utterly flies in the face of his periodic dismissals of his material as silly superstition. Hence the book can be, and generally has been, read as a kind of grammar of the human soul: The Great Mother. The Cosmic Fire. The Dying God. The Scapegoat.

Then he further comments:

The reason the book remains so popular is that no subsequent anthropologist has produced anything remotely like it … But this immediately brings up two problems. The first is logical. If we have progressed beyond progressivist views, then progressive views are on some fundamental level correct, or we could not have progressed beyond them. But if that is true, then we have not progressed beyond them. Which means Frazer is not wrong. (Or if he is wrong, it’s because he has embraced the wrong kind of evolutionism, and it is incumbent on his critics to explain what is the right kind. But of course no one attempts to do that.)

The second dilemma is that if we reject Frazer as a condescending snob, we fall in danger of becoming one … Wittgenstein also clearly felt the way in which Frazer was stupid was, still, somehow, profoundly important—otherwise he would not have continued for the rest of his life to work and rework his responses to the Golden Bough (and not just to Frazer’s material, also to his interpretations). Over the course of these reflections, he anticipated, in one form or another, most of the approaches to ritual that anthropologists, too, were to develop in mid-century. But this was incidental.

Rex redux: who won the duel?

Eyewitnesses have reported slight variations in the details of the events that took place that evening at Cambridge.8 The duel has been analyzed from various points of view, but it is my belief that Wittgenstein, perhaps acting unconsciously on the basis of a decades-long obsession with Frazer’s Golden Bough and the figure of the Rex nemorensis, drew Popper — whom he perceived as a challenger to his position as the most prominent philosopher at Cambridge — into a single-combat duel.9

In my opinion, Wittgenstein himself, in his Remarks on Frazer, foreshadowed his own capability for acting in a symbolic manner:

When I am angry about something, I sometimes hit the ground or a tree with my cane. But surely, I do not believe that the ground is at fault or that the hitting would help matters. “I vent my anger.” And all rites are of this kind. One can call such practices instinctual behavior. — And a historical explanation, for instance that I or my ancestors earlier believed that hitting the ground would help, is mere shadow-boxing, for these [sic] are superfluous assumptions that explain nothing. What is important is the semblance of the practice to an act of punishment, but more than this semblance cannot be stated.

Once such a phenomenon is brought into relation with an instinct that I possess myself, it thus constitutes the desired explanation; that is, one that resolves this particular difficulty.10

However, what he misses is the fact that he (like you, and I, and everyone) cannot always tell when actions are aimed toward a particular, self-acknowledged goal, and some of them — such as his attacks on his young pupils and the assault11 on Popper — are too shameful to admit. Here, he has only confessed to directing aggression toward the ground or a tree.

Many have commented on Wittgenstein’s apparent neurospiciness and on the distorting effects on morals and behavior that growing up with so much wealth, privilege, and genius might create. But these factors don’t seem to get to the heart of the problem. Most rich people, neurospicy people, and even those who are both, would never behave this way.

When I sought a modern perspective or model that could account for the philosopher’s bizarre fight with his colleague, John Grigsby suggested an apt solution: Carl Jung’s “inflation.”

Jung defined inflation — an unconscious psychic condition – as expansion of the personality beyond its proper limits by identification with the persona or with an archetype, or in pathological cases with a historical or religious figure. It produces an exaggerated sense of one’s self-importance and is usually compensated by feelings of inferiority (Jung 1934—1939, 1963). Most of Jung’s comments about inflation are concerned with an identification of the ego or consciousness with the numinosity of an archetype (Jung 1934/1950. 1952), leading to a distortion or even dissolution of the former.

After Wittgenstein left the room, it seemed that Popper had won the duel, for he had used the tools proper to philosophy (words, logic, reasoning) instead of archaic, barbaric methods of demonstrating supremacy. But over the longer course of time, it seems that Wittgenstein did, indeed, defend his position as Rex Cambridgensis. He consistently appears way, way ahead of Popper in polls that ask professional philosophers to rank the greats, and he is often reckoned as the leading analytical philosopher of the twentieth century. Popper’s "Paradox of Tolerance” has had a bit of a revival lately, but it doesn’t seem likely he will even touch the toes of Wittgenstein’s colossus.

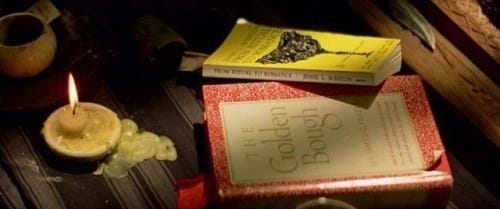

As for Frazer? I don’t think we’ve heard the last from him either. Just to recap, some of those who acknowledge The Golden Bough as an influence include William Butler Yeats (“Sailing to Byzantium” and his work in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn); Aleister Crowley; Jessie Weston (From Ritual to Romance, a directly cited inspiration for Eliot’s The Waste Land); James Joyce; Robert Graves (The White Goddess); H.P. Lovecraft (The Golden Bough was given an explicit callout in “The Call of Cthulu”; T.S. Eliot, (The Waste Land); William Carlos Williams; Sigmund Freud (Totem and Taboo); Carl Jung; Ernest Hemingway, William Gaddis, D.H. Lawrence; Joseph Campbell; Jim Morrison; Francis Ford Copola (Apocalypse Now); and Camille Paglia.

A still showing Kurz’s private library in Apocalypse Now. We’re looking at The Golden Bough, and Jessie Weston’s From Ritual to Romance, which was inspired by it. Source.

What’s coming next

In the third part of this three-part series, look forward to a discussion of the mysterious figure of the corn wolf, which is one of the themes Frazer discusses in The Golden Bough. It was picked up by Wittgenstein, who — of course — criticized it, and it is now being rediscovered by contemporary anthropologists.

Is the corn wolf the wild ancestor or relative of the corn dog? Not exactly, but also yes — yes it is. Find out how in the next article.

Be sure to subscribe so you won’t miss it.

The theory that there is a social evolutionary process from magic to religion to science cannot be backed up empirically (mainly because of how fuzzy and subjective the categories are once you remove the colonial context).

But has the modernizing process really led to a decline in magic, or to “disenchantment”? For really good arguments that no such thing has taken place, see The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences, by Joseph A. J. Storm. Here is the official description of the book:

A great many theorists have argued that the defining feature of modernity is that people no longer believe in spirits, myths, or magic. Jason Ā. Josephson-Storm argues that as broad cultural history goes, this narrative is wrong, as attempts to suppress magic have failed more often than they have succeeded. Even the human sciences have been more enchanted than is commonly supposed. But that raises the question: How did a magical, spiritualist, mesmerized Europe ever convince itself that it was disenchanted?

Josephson-Storm traces the history of the myth of disenchantment in the births of philosophy, anthropology, sociology, folklore, psychoanalysis, and religious studies. Ironically, the myth of mythless modernity formed at the very time that Britain, France, and Germany were in the midst of occult and spiritualist revivals. Indeed, Josephson-Storm argues, these disciplines’ founding figures were not only aware of, but profoundly enmeshed in, the occult milieu; and it was specifically in response to this burgeoning culture of spirits and magic that they produced notions of a disenchanted world.

Among his other remarkable achievements, Comte was also probably the first philosopher of science. He developed individual philosophies of mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biology, as well as an overarching theory that categorized all these sciences and set them in hierarchical relation to one another.

In order to develop society in the most beneficial (rational) direction, he proposed a new “religion of humanity” that would have no gods or other supernatural elements. The object of worship would be humanity itself, which needed to be loved, known, and served. His followers created a liturgical calendar with rituals for public worship, prayers, hymns and sacraments that were inspired by Catholic practices, and they encouraged the honoring of deceased great men as heroes and inspirations to the living. Sociology, the new science of society, would be source of knowledge of the laws of the human order, which would be based on observable reality and science would enable people to live their lives as fully as possible. Like Marx, Comte believed in an inevitable force driving human social evolution; however, the evolution he believed in was intellectual rather than social. Comte predicted that each branch of human knowledge would develop through theological [childish belief in Divine influence in all events] and metaphysical [reasoning, questioning of authority and religion] stages, ultimately developing into a positive stage in which people realize the impossibility of having one complete law and instead practice scientific observation and classification of various phenomena in order to derive the forces that govern society. (Source: a handout I created for an Intro to Sociology class I used to teach.)

See Richard Carrier’s litany of dying/rising gods and other features Christianity and its central figure had in common with other cults of the Mediterranean cultural region.

This comment comes from a blog post by Mackenzie Wark on Verso’s web pages. The author is primarily discussing Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s Cannibal Metaphysics.

This raises the question of what he could have meant by “savagery.” After all, Wittgenstein was known for vicious physical attacks on people who irritated him — even schoolchildren he was teaching — slapping them, pulling their hair, pulling one girl’s ears hard enough to make them bleed, and even knocking a boy unconscious. (It’s possible that his wealthy parents helped him avoid any serious consequences for these actions) The authors of Wittgenstein’s Poker also note that he had a known history of waving sticks at people.

The issue was about whether philosophy could be used to address genuine problems, such as the mind/body relationship, the ideal structure for society, and the the nature of science. He rejected Wittgenstein’s proposition that these were all just linguistic puzzles.

One of the most sublime ironies in the whole affair is that conflicting and contentious testimonies were given by eyewitnesses. All of them were scholars professionally concerned with theories of epistemology (the grounds of knowledge), understanding, and truth. Yet they could not agree on what happened. It is my contention that the mytical perspective should not be neglected. What stand out most powerfully in everyone’s testimonies, and the element remained fixed in everyone’s minds was the red-hot poker.

According to Suetonius, the mad emperor Caligula co-opted the “original” Rex nemorensis phenomenon, and turned it into a themed gladiator spectacle. Perhaps, one might speculate, the forces of myth and spectacle tend to overwhelm more nuanced perceptions.

Ideas that were proposed which didn’t fit included:

Bovarysme — “the tendency towards escapist daydreaming in which the dreamer imagines themself to be a hero or heroine in a romance, whilst ignoring the everyday realities of the situation.“ It doesn’t work here, because no escapist daydreaming was involved.

LARPing — No, because Wittgenstein and Popper hadn’t invited others to participate in the drama, and no costumes were involved.

Method acting/Stanislawski method/method cosplay — No, because the identification wasn’t deliberate.

Trance identification — Also no, because no trance states were involved, and LW was probably not consciously attempting to identify himself with the Rex nemorensis.

Something like a Messiah complex/God complex/Cassandra complex — Again no, because LW was not consciously attempting to influence people so they would see him in this kind of role.

A further question arises in my mind of whether Wittgenstein wasn’t using Popper as a stand-in for Frazer. Adding speculation to assumption, perhaps it could have been because he didn’t feel capable of confronting him? In a footnote to Chapter 1 of Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Mythology in Our Language — Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough, (2019) Stephan Palmié comments:

Intriguingly, both Frazer and Wittgenstein were Fellows of Trinity College, and technically overlapped there for considerable amounts of time. However, Brian Clack (1999: 177n5) is surely right in arguing that the likelihood that they would ever have interacted is small. Josef Rothhaupt (2016: 76) notes the curious coincidence that Frazer presented his inaugural William Wyse lectures on “The Fear of the Dead in Primitive Religion” during the Michaelmas Term of 1932 and May Term of 1933 on the exact days and at the exact time of day that Wittgenstein was himself lecturing. The one exception was Frazer’s lecture on May 8, 1933, which Wittgenstein could have attended (and even though G. E. Moore’s lecture notes show that Wittgenstein had mentioned Frazer earlier, he did make reference to him in his own lecture on May 9, 1933).

Quoted from Palmié’s translation on p. 54 of his edited volume cited above.

“Assault”? Indeed it was, even if he did not touch Popper with the poker. In Common Law (as well as in the legal codes of the United States and many other countries), the essential elements of assault “consist of an act intended to cause an apprehension of harmful or offensive contact that causes apprehension of such contact in the victim.

The act required for an assault must be overt. Although words alone are insufficient, they might create an assault when coupled with some action that indicates the ability to carry out the threat. A mere threat to harm is not an assault; however, a threat combined with a raised fist might be sufficient if it causes a reasonable apprehension of harm in the victim.” The threatening gesture with the poker qualifies.

Still reading this. Love me some Frazer, though. I’ll have to read more of Wittgenstein on Frazer.

Oh, what a lovely, crunchy, satisfying read that was. Looking forward to Part 3!