White deer as symbols of worldy and spiritual power

Images of White Deer in Art – Part I – Classical, Medieval, and Renaissance Motifs

Why deer? Why white ones?

In The White Deer, I discuss the symbolism of the color white and of deer at length. There is no need to rehash all the details here, but the radiant gist is that for many reasons, whiteness is often associated with spiritual messages, as well as with danger and death.

Deer have very specific sets of associations which differ from the ones attached to domestic animals such as cattle and horses. For one thing, outside of the steppes and subarctic regions where reindeer are herded, deer did not contribute to the rural domestic economy. On the contrary, they were pests who ate crops, fruits, vegetables, and other garden plants. But more importantly, they have been regarded as a prestigious prize of the chase, which is often reserved either exclusively or mainly for those of high rank.

For this reason, deer are often symbolically associated with rulership, status, and power. And white deer, because of their connection with death and with otherworlds and spiritual forces, are particularly potent. In artwork with white deer, we find complex and ambivalent symbolism where human, animal, and spiritual realms overlap. Yet even in images that stake claims for religious or political supremacy there are many quirks in the depictions, and we can find moments of raw human pathos, and also of humor.

The legends of Placidus/Eustace and of Saint Hubert

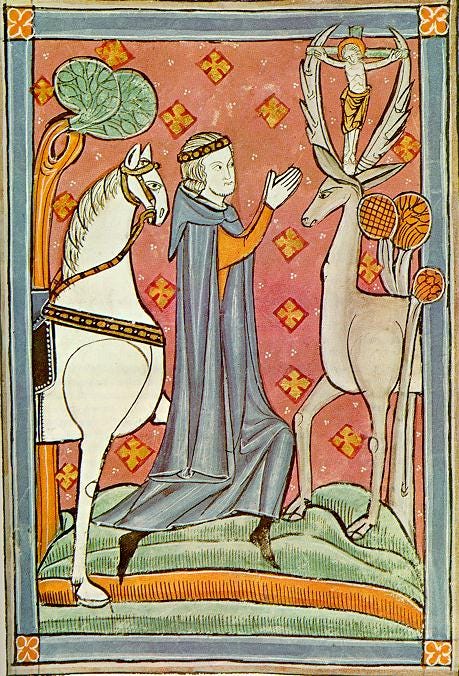

In these annotated galleries we’re going to wander through groves of visual imagery that complements the themes discussed in my book. I’ll begin this gallery by introducing Saint Eustace (né Placidus), a second-century forerunner to the much more famous St. Hubert(us). His story was popularized in Jacobus de Voraigne’s The Golden Legend – a collection of hagiographies compiled in the 13th century. There, Voraigne tells that Placidus had set off in chase after a herd of harts, but one was “more fair and greater than the others”. He followed the stag into the thickest part of the forest, but then he saw a crucifix between the animal’s antlers. The stag spoke to him in Christ’s voice, appealing to him to let the bishop baptize him and convert him to Christianity. This moment of revelation and conversion is depicted in most images of the saint.

In this one, the stag has a very severe look and the horse seems distinctly displeased.

I have been unable to find the artist’s name, and the image is attributed as “13th c. English manuscript; Venice, Marciana Library,” which means that it may have been inspired by Voraigne’s text.

The photograph below captures a large wall painting created in Canterbury Cathedral around 1480. This image from Lella Lee was the best I could find. The light and viewing angle inside the cathedral seem to make it very difficult to get a good, clear shot of the whole painting.

The relative proportions of humans, animals, trees, buildings, etc. are very out of balance, and the key detail that gives meaning to the whole scene, the figure between the stag’s antlers, looks much more relaxed than one might expect: this casually contrappostoed Christ appears to be dancing between two pitchforks. The stag here is very horselike, and the symmetry between him and Eustace’s mount suggests that the mystic visionary stands in a liminal space between the realms of the domestic and the wild.

After his conversion, Eustace’s new faith was going to be tested in many ways, but he remained true to it. There are obvious similarities between Eustace’s story and the Biblical story of Job, as well as other figures who must endure “trials of faith” that include losing family members. Two of Eustace’s difficulties are represented by a charismatic wolf and lion on the scene who are, respectively, pacified and grinning because they have just devoured two of Eustace’s sons.

The wolf looks deceptively cute and innocent:

But here’s the lion: he’s menacing a tiny castle and reveling in his full belly, and is oblivious to his ludicrously bad hair day:

Elsewhere in the picture the artist added a detail that not all hagiographers agree with: Eustace’s wife and remaining sons being roasted alive because they refused to make pagan sacrifices.

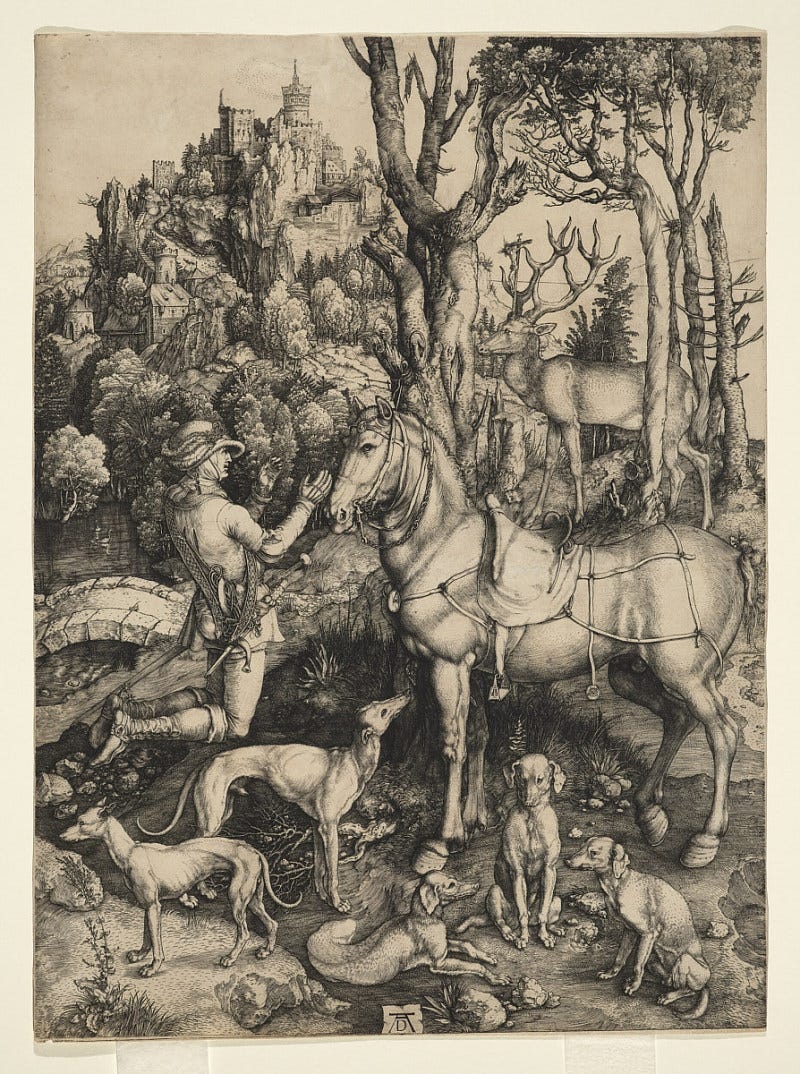

The next portrayal of St. Eustace is Albrecht Dürer’s largest copper engraving (ca. 1501) – though it is surely not among his best works. The image is crammed with closely-observed details, but the portrayals of Eustace and the stag are very stiff. This makes the piece feel more like an allegorical tableau rather than a naturalistic scene. The holy stag, moreover, looks like he couldn’t possibly care less, unlike the horse, who is giving us a sly wink. The hunting hounds meanwhile, are clearly off duty and not interested in whatever their master is doing. The mismatch between the main subjects and their surroundings and supporting cast is, in my view, more disorienting than the odd proportions in the Canterbury painting, which at least has a narrative flow to it.

This etching depicting St. Eustace (below) was created by the Italian prodigy Elisabetta Sirani. Sirani was a painter and printmaker who was successful and sought-after in Bologna for her Baroque-style work. Already an independent artist at the age of 19, she was only 27 when she met her untimely death. At the time, some believed it was due to poisoning, though it was more likely peritonitis. Read more about her life and works here.

Just as the deer in Sirani’s 1655 woodcut seems to be an integral part of the landscape, the landscape itself dynamically mirrors the tremendous forces released at the moment of the irruption of a sacred power. Clutching at his heart, Placidus/Eustace appears overwhelmed by the apparition, and his horse also seems awestruck. His dog probably cannot see the stag, but his sharp senses make him look in the right direction. Using a lighter touch Sirani has, in my opinion, produced a much better work.

The story of St. Hubert(us), the “Apostle of the Ardennes” is similar in many details to the hagiography of Placidus/Eustace, and so is his iconography. Although Hubert already was a Christian before his moment of revelation, he did not respect the bans on engaging in sport (hunting) on holy days. Like his predecessor, he also chased a magnificent stag into the deep forest, and saw that he had a crucifix between his antlers. He was admonished to mend his ways, seek out Bishop Lambert, and learn to live a holy life. He did all of this, and become a hermit, then a priest, and finally the first bishop of Liège.

Egon Schiele’s The Vision of St. Hubert (1916) was painted with oil on a wooden panel. The stag has a natural majesty, and Hubert is quiet and attentive to the lessons he is given. The dog seems to echo Hubert’s response, and does not distract from the piety and grace of the scene.

Finally, let’s take a look an image that is familiar to many: a bottle of Jägermeister, which displays the holy stag’s head on its label. Yep, it really is the same deer – Jägermeister explicitly wanted to honor Hubert, who became the patron saint of hunters, with its logo. In order to spread the teachings attibuted to the saint, they incorporate Oskar von Riesenthal’s poem “Waidmannsheil” (Hunter’s Salute) inside the green frame that runs just inside the edges of the label. Approximately translated, it says: “This is the hunter’s shield of honor; he protects and looks after his game. He hunts sportsmanlike; honoring the Creator in the creatures, as is fitting.”

King Rich-hart and his stag emblem

Some six centuries after Hubert lived and died, the white deer was adopted by King Richard II of England as his “emblem” – not his official coat of arms, but a personal symbol. It is likely that the choice relates to the pun Richard / “rich hart”. (Some may be interested in comparing this with the emblem of another English king. The man who was first known as Richard of York, then Richard, Duke of Gloucester, eventually became Richard III, and his device was a white boar. Some believe Richard III was punning on “Ebor,” a contraction of Eboracum, the Latin name for York. The boar’s white color may relate to Norse or Celtic myths and / or to the white roses of York.)

The Wilton Diptych (c. 1395-1399) consists of two hinged oakwood panels. Tempera images painted in the International Gothic Style decorate both the inside and outside. The inner image on the left panel portrays King Richard II kneeling in the company of three of his patron saints.

Together, they are offering devotion to the Virgin Mary and her infant son, who are surrounded by angels (right panel). Richard's gold and vermilion robe is decorated with his white hart and the rosemary emblem of his wife, Anne of Bohemia. Even more interestingly, all the angels are wearing Richard II's livery badges with the same hart. These badges had become very controversial in the late 14th century because they were given to the members of a lord's small private army that he could to assert his will against vassals and subjects. Parliament repeatedly attempted to restrict their use because of the abuse of these forces.

The diptych’s outer paintings show Richard II's coat of arms on one side and the white stag emblem on the other.

Here is the coat of arms:

And here is Richard’s stag:

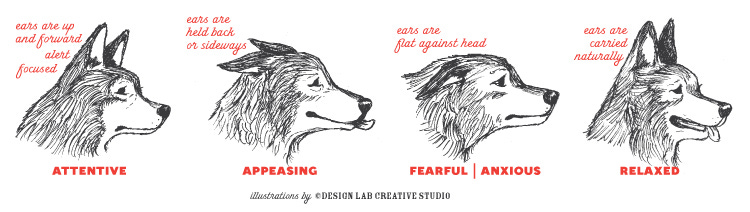

The animal’s pose is meek and submissive, and any dog owner will recognize that his ear position is similar to the way their pet shows an “appeasing” disposition:

Significantly, the stag wears a crown-shaped golden collar around his neck attached to a chain. But the chain is not attached to anything – it’s a dangling signifier anchored only in empty space.

This brings forward some interesting and ambiguous symbolism: the stag’s collar and chain were intended to represent Richard’s burden and responsibility of kingship, yet the animal is shown captive. The king wanted to prove that he had a divine right to rule, but that wasn’t enough, because he could not enforce his will without the help of his retainers and henchmen, who received the livery badges to pin on their outerwear. The paradox here is that the stag cannot lend Richard any legitimacy if it is already entirely identified with him, and/or in his service. In my view, that’s why the end of the chain cannot be held by anyone or attached to anything. He needed to present a higher power showing him favor. He’s not quite cheeky enough to put livery badges on Mary and Jesus, but they seem to have no objection to the angels wearing them, and they are shown obliging him with benediction in return for his homage.

The Wilton Diptych displays multiple sources of Richard’s claims to legitimacy: his own self-assertion (the hart), divine favor, the livery-wearing angelic minions, and family prerogative (lots of symbolism that I don’t have space to discuss here, but for starters there is the deliberate resemblance between the saints and his relatives). It seemed like Richard II was trying everything, hoping something would work. But as we know from history and from Shakespeare, it didn’t turn out so well.

Now it should be clear why we do not see the motifs of collars and chains on the stags that appear to Eustace and Hubert: these men were prostrating themselves in front of the emanation of a power they considered higher than themselves, and they were experiencing moments of profound self-transformation, while Richard II wanted to put his “brand” everywhere — even in the heavenly realms.

Stags in classical and medieval bestiaries

Yet Richard had certainly not invented the motif of a white deer wearing a golden collar himself; the tradition goes back to classical antiquity. Perhaps the first written example is found in a paradoxography (paradoxographies were collections of “believe it or not” tales that related to supernatural and anomalous phenomena, much like The Sun and other tabloid publications in the twentieth century). The author of the one in question is only known today as “Pseudo-Aristotle”. Whoever they were, they relate a legend about Diomedes — one of the warriors at the siege of Troy made famous in Homer’s Iliad – that tells of a nobly adorned deer. Diomedes, they wrote, had consecrated a white hart to Artemis and placed a golden collar around his neck. Okay, you might say — this could be real — but the incredible part of the story is that the hart was allegedly found 800 years later, still wearing the collar!

The natural philosopher and historian Pliny the Elder also ascribed magical virtues to deer, including incredible lifespans; not 800 years, perhaps, but he claimed that some had been captured one hundred years after they had been fitted with golden collars by Alexander the Great.

Why did stags live so long? It was (allegedly) thanks to their habit of supplementing their diet with venomous snakes! And they were able to neutralize the poison thanks to their habit of drinking copious amounts of water. [Remember, kids, stay well hydrated! ] And here’s another benefit of hydration: medieval bestiaries described how a stag will pursue his enemy/prey, and spray water out of his mouth to flood the snake’s underground den. When the serpent emerges, the stag tramples it to death.

Alternately, he might suck the snake out of its hole and devour it. This version must have been inspired by Aelian’s On the Nature of Animals (ca 2nd-3rd c. CE), where he writes:

A deer defeats a snake by an extraordinary gift that Nature has bestowed. And the fiercest snake lying in its den cannot escape, but the deer applies its nostrils to the spot where the venomous creature lurks, breathes into it with the utmost force, attracts it by the spell, as it were, of its breath, draws it forth against its will, and when it peeps out, begins to eat it. Especially in the winter does it do this.

In the Christian era the allegory of stags killing snakes was a reminder to humankind to overcome the “poisons” of the devil by consuming the pure water of wisdom. The yearly shedding of the stag’s antlers was also considered symbolic of resurrection. See the British Library blog for more.

The illustration below is from a work known as “Bestiary with Theological Texts” and catalogued by British Library as Royal MS 12 C XIX.

Lest anyone scoff too much at the “unrealistic” medieval image, I would like them to consider the Hawaiian monk seal’s peculiar habit:

Australian cattle have also been documented with snakes in their mouths; possibly possibly just killing them, or possibly because they have a taste for spicy danger noodles.

Deer with royal collars as renovatio

But let us leave this digression: I want to return to how the associations of collared deer with kingship persisted as a theme that harks back to classical tradition.

Francisco Petrarch wrote in Sonnet 190 in his Canzoniere:

A white doe appeared before me

On the greensward, with horns of gold,

Between two river banks, in the shade of a laurel tree

As the sun rose over the springtime.

She looked so sweetly proud,

that I left all my toil to follow her:

As the miser whose delight in seeking treasure

Assuages all his pains.

Around her fair neck was writ in diamond and topaz

“Touch me not, for Caesar wills my freedom”

The sun was already nearing the noonday peak,

And my eyes were weary from gazing, but not sated

When I fell into the water, and she vanished

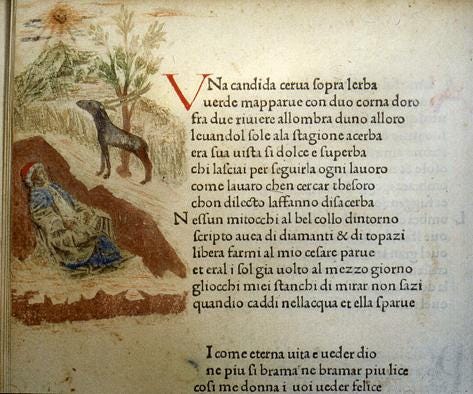

Here is a hand-illustrated page by an unknown artist in a copy of Petrarch’s Canzoniere. Despite what the poem says, they did not make the doe white. Additionally, she has antlers, which are only found in mythical does and in reindeer.

In Petrarch’s poetic vision, as in the Greek stories, the white doe is only safe because she enjoys the ruler’s personal protection, symbolized by the collar, which warns people not to interfere with his free-ranging pet. It is notable that this doe must have had an extraordinarily long lifespan in order to still be wearing it.

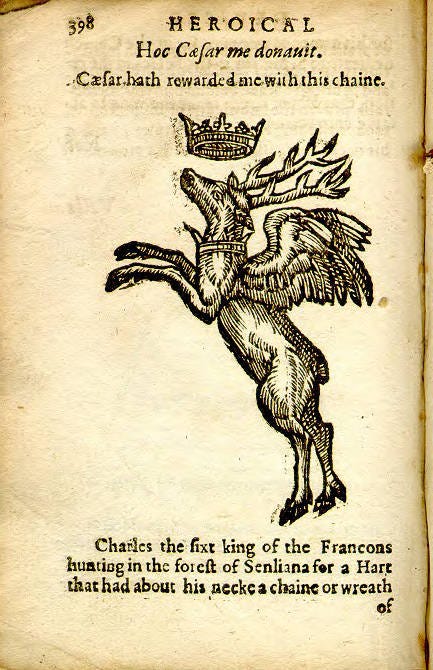

There is also a legend told about King Charles VI of France, who was first known as Charles the Beloved, and later as Charles the Mad. He began his reign at age 11, and at age 12, already “fond of the chase,” it is said he came upon deer bearing a collar inscribed with the suspiciously medieval Latin spelling “Hoc michi Caesar donavit.” In English, that’s “Caesar rewarded me with this,” which is unlikely, since Caesar had been dead for 1400 years.

This image, taken from Claude Paradin’s Devises heroïques (1557), shows the motto and a winged stag with crown and collar motifs:

Much later, Napoleon allegedly captured a large stag and had a gilded bronze collar soldered around his neck with the inscription “The Empress Josephine gave this stag its life on 8th September 1808.”

King Christian IV of Denmark also allegedly captured a stag that wore a collar with the claim that it had been freed by King Frode. The symbolism and “tradition” of either putting the collar on a deer or claiming to find one that had been collared by a predecessor in office obviously harks back to a Roman legacy, though these two renovatio stories are most likely apocryphal.

Did any Romans use deer, or white does, in their personal repertoire of symbols? One attested example is found in Plutarch’s Life of Sertorius, where the author recounts how the general and statesman made use of a (real, living) tame white doe to bamboozle credulous countrypeople. Sertorius pretended that his doe was an oracle of Diana, which proved he was the recipient of divine favor. Illustration of Cervia Disertorio (below).

This is akin to Richard II’s practice of wielding the white stag emblem in the attempt to create and project personal power, though Sertorius had a living animal.

I have already discussed the multiplicity of motifs he availed himself of, but there is also already a paradox inherent in the position of the animal being both protected and pursued by elites. For hunters, too, were exposed to dangers, both natural and supernatural. Hunting large game was a privilege that not only granted the hunters spoils to take home and enjoy and divide, but it was also a test of their fitness as leaders.

This is why so many stories tell us of liminal spaces opening up when the noble huntsman is led into the deepest part of the forest — it is there where the balance of powers between humans, supernatural figures, and the land; between kings and commoners; and between men and women are negotiated.

Coming in the next post:

The motifs of hunting, kingship, and deer appear very different in Celtic or Celtic-influenced stories than in those influenced by the classical tradition. This is because the original forms of kingship among Celtic peoples were not hereditary; rather, kings had to face initial tests to become qualified for their rank, and had to prove their virtue on on ongoing basis. Thus, there is less apparent paradox in their identification with the symbol of a deer. Additionally, there are older levels of lore that suggest sacrificial rites in which the ruler would have to give himself back to the land for the benefit of all, much like a hunted animal.

When a white deer appears in Celtic stories, it is often bearing a warning that someone has transgressed boundaries of morality, sustainability, or even the boundaries between the human world and the world of fateful powers.

Make sure to subscribe so you won’t miss my next annotated gallery of images: The White Deer as a Liminal Message Bearer.

So well researched but your links were not working, I didn’t find the previous essays via the links

Wonderful to stumble upon this post, after having seen two white deer in the woods above our valley the other evening!