Medusa plaque at the Fontana della Gorgone in Nemi.1 This is one of the many reasons I hope to visit Nemi, a place with a rich, mysterious history and culture, some of which I have already written about in a 3-part series on this blog.

In several parts of my book The White Deer I discuss loathly ladies, an archetypal figure that appears in English, Welsh, and Irish literature. They are characterized by an ability to shapeshift from young and fair to old and unattractive, blighted, or even bestial and monstrous.

However, their duality is not only in appearance: loathly ladies can bring forward threats or challenges, but also grant boons — particularly, bestowing the right to rule upon a worthy man.

Often, at the beginning of the story where a loathly lady appears, things look anything but auspicious. Usually, the land and people are suffering; then it transpires that a crime was committed, upon which judgment is passed. Often, the crime is a rape; sometimes it’s the killing of a white deer; and in some stories it’s both. After the transgression has been acknowledged, the loathly lady makes her appearance, poses a riddle, and selects the lover she wants. After the riddle is solved, a marriage takes place between the hero and the lady, whom he must willingly embrace and please on their wedding night. In the marriage chamber, the groom makes a fateful choice: if he honors and uplifts his bride and treats her as an equal partner, all will be well.

Much more is at stake than just a couple’s marital harmony: the way the mysterious lady with a murky back story is received by the unsuspecting young male ruler or adept for the throne defines the relationship he is to have with the land during his reign and the happiness of his people.

It is clear that someone who disposes of these powers is no ordinary woman. The loathly partakes of both aspects of divine mystery described by Rudolf Otto: the mysterium fascinans (the aspect of divinity that is beautiful and intriguing) and the mysterium tremendum (its polar opposite: the “terrifying, repulsive, and yet inspiring end of the numinous spectrum”).

This wonderful illustration of Lady Ragnelle was made by the English artist James Hutton. It was one of six works expressly commissioned from him to illustrate my book, The White Deer.

Two of the necessary elements in all loathly lady tales are that she is noble, and she is always encountered in a wild place. She is not only a symbol of Nature, with its foul and fair moods, with its spring blossoms and bountiful harvests and its droughts, blights, and winter storms, but an embodied guardian of the land who takes an interest in human affairs because they affect her realm as well. As the tales make clear, how the land and its inhabitants are treated is integrally connected with the way women are treated. Rape is often associated in these tales, as well as in stories about well maidens, with a loss of health and vitality of the land and waters. Sometimes, acts of beheading are part of the Christian-era origin tales for healing springs, which is … interesting … to say the least.

My explorations of these topics have led me to see some fascinating resemblances between loathly ladies and the mythical figure of Medusa. I am not claiming a direct lineage, but I believe that digging deep into Medusa’s past reveals a startling wealth of parallel elements and that reading the stories together can bring new insights.

Medusa, by Christopher Lovell.

Perseus, the Gorgon-slayer

Traces of Medusa’s story as we know it can be found as far back as Greece’s Archaic Age; however, the elements that most are familiar with are taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ovid’s account isn’t really centered on the Gorgon: it’s framed as a story about Perseus, the son of Zeus and a mortal woman named Danaë. (The story of the original owner of the “foul head” is brought up at the request of a prince attending a noble banquet.)

Perseus’ tale begins when Danaë’s father, King Acrisius of Argos, had consulted the Oracle at Delphi, who gave him a prophecy that he would one day be killed by his daughter's son. In order to prevent her from conceiving a child, Acrisius imprisoned the princess in a bronze chamber in the palace courtyard. While no one could approach from the ground, this room was open to the sky, and randy old Zeus came to visit Danaë disguised as a shower of gold.2

Gustav Klimt’s Symbolist Danaë (1907). The princess is wrapped in royal purple robes as she receives her visitation.

When Acrisius discovered that his daughter had given birth to a son, he cast the two of them into the sea in a well-sealed wooden chest, thus leaving their fate up to Poseidon.

Danae and the Infant Perseus Cast Out to Sea by Acrisius. Engraving by Giorgio Ghisi (1543).

The chest washed ashore on the island of Seriphos, with both inhabitants unharmed. There, a fisherman discovered them and took the shipwrecked duo home. Dictys became the young princess’s consort and he raised Perseus as if he were his own son.

Perseus protected his mother as well as he could from the designs of Dictys’ brother, Polydectes, who was the king of the island. When Polydectes invited his friends to a feast, he asked each of them to bring a horse as a gift. The other guests were able to do this, but Perseus could not afford one, so instead he told the king to name whatever he wished for, and said he would not refuse it. The king’s desire was that Perseus would bring back the head of the Gorgon Medusa. Polydectes threatened that if Perseus did not succeed in this task he would take Danaë by force. Perseus left, and Polydectes thought he had seen the last of the rash young man.

Perseus didn’t have to accomplish his deed alone: the Graeae as well as gods and nymphs helped him. He was given the use of magical tools: winged sandals that made him able to fly, a sickle made of adamant (a mythical kind of diamond), a special leather knapsack, and Hades’ helmet of invisibility in order to accomplish his mission. As his chief abettor, Minerva lent Perseus a polished bronze shield and explained how he was to use it.

(There is no solidarity between female characters in the story, as evidenced first by the Graeae betraying their sister,3 and by the goddess Minerva [Athena]4 pursuing a vendetta against Medusa to the point where she sends a well-equipped hit man after her.) Why? The Roman historian Tacitus wrote: “It is a principle of nature to hate those whom you have injured.”

Perseus crept along the “hidden tracks, through rocks bristling with shaggy trees” to where the Gorgon — and all the snakes on her head — slept peacefully in a cave. Using the shield as a mirror, the headhunter crept in close without having to look at her directly, which would, of course, have turned him to stone like all the other men and animals who had beheld her.

After he struck her fearsome head off, he popped it into the bag, and where her head had separated from her body, Pegasus (the winged horse) and a giant named Chrysaor sprung forth. Both of these marvels were her children from a violent encounter that I will describe below.

Medusa’s Gorgon sisters gave chase through the air, but the helmet of invisibility made it impossible for them to track Perseus effectively.

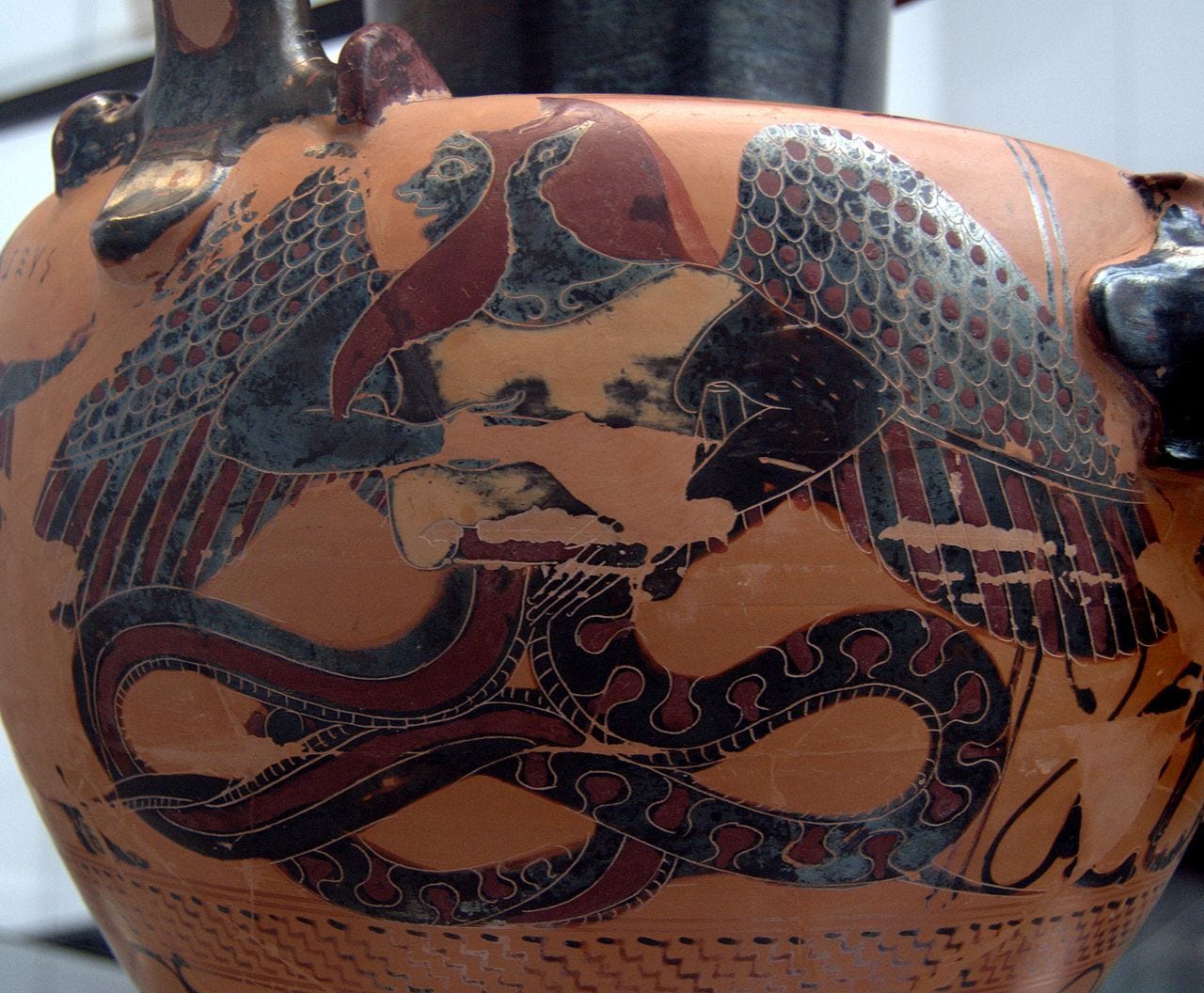

This detail from a dinos punch bowl (ca 580 BCE) was decorated by an anonymous painter, known today as "The Gorgon Painter." It depicts Perseus pursued by Medusa’s sisters.

Perseus had other adventures on the way home (notably, saving Andromeda from the terrible sea monster Cetus and then marrying her), but for our purposes, what’s important is that he protected his mother from Polydectes’ foul intentions. Perseus and Andromeda had seven sons and two daughters, and established the Perseid dynasty.

And this, in my view, brings us fully back to the idea of the loathly lady as a kingmaker. However, Medusa is a tragically diminished figure in comparison with, for instance, Ragnelle. She who petrified men was herself frozen in her loathly aspect, for there was no reciprocation of sovereignty and self-determination. And despite being fertile — pregnant — she was unable to bring forth life until she was killed.

We can also say that in comparison with many Celtic tales, two key roles have been reversed: the sovereignty-granter Medusa (whose name means Queen) dies, and the man who killed her becomes immortal, as symbolized by his placement among the constellations.

Edward Burne-Jones The Baleful Head (1885). Here, Perseus is showing his wife Andromeda the head of Medusa, safely reflected in a well. In many ways, Andromeda serves as a foil to Medusa.

In the aftermath of these adventures, Perseus sacrificed to the gods to give thanks, returned the magical objects to their owners, and gave Medusa’s head to Athena/Minerva, who set it on her shield (aegis). Was that what Athena actually wanted the whole time? One wonders!5

As for King Acrisius, who had set off this chain of events in a futile effort to prevent the Oracle of Delphi’s prophecy from coming true, there are several versions of how he met his inevitable fate. Pausanias relates that it happened when the king was visiting athletic games in Larissa: he got clonked in the head with a flying quoit (Perseus was not involved). Pseudo-Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca says Acrisius went into voluntary exile, where Perseus was competing in a discus tournament. When his throw went off course it killed his grandfather. A third tradition has Perseus using Medusa’s head against his grandfather when he is accused of having lied about killing her.

Priestess of Delphi by John Collier (1891) — detail.

Medusa as rape victim

Over the last few decades, more people have started taking an interest in Medusa’s back story instead of simply seeing her as the conquest of a monster-slaying hero. Plenty of articles have appeared even in the last 5-10 years retelling the story of the lovely young priestess who met a ghastly fate.

Here’s that tale, which is also from Ovid: Medusa had taken vows of chastity, like other priestesses who served in Athena’s temple. However, unfortunately, Poseidon found the young priestess irresistible and tried to seduce her. Medusa fled from him. Stung by the rejection, Poseidon raped her in the goddess’s sanctum. Athena knew what was happening, but hid her eyes behind her aegis and did not attempt to help Medusa.

On the contrary: the virgin goddess was enraged — however, she did not direct her wrath toward her uncle, the mighty sea god. Some think Athena envied Medusa’s beauty (which, let’s face it, seems unlikely), while others hold the opinion that she was mainly outraged by the defilement of her sacred space. In any case, since only Zeus could have punished Poseidon, it was Medusa who was made to bear responsibility for what happened and the culprit was never brought to justice. (A woman having horrible consequences from an affair or from being raped by a god was not at all unusual then, just as “honor killings”6 and battery of women suspected of having affairs are still widespread around the world today.)

Whatever the reason, Athena cursed poor Medusa by turning her hair, which had once been her most beautiful feature, into snakes, and giving her a deadly stare that turned anyone who looked into her eyes into a stone statue.

Heart of Stone, by Michelle Celebrielle on DeviantArt. Perhaps we could consider Medusa the patron saint of art collectors (for her wonderful garden of statuary).

Medusa as a #MeToo mascot

Medusa has been co-opted by academic feminists, who interpret the myth of her beheading as the “decapitation” of early matriarchal societies and the replacement of chthonic cults with agrarian ones. Whatever one thinks about Marija Gimbutas and Joseph Campbell, the point here is that this view has been, and remains very influential.7

I cannot find the origin or creator of this mural. It’s all over the internet without attribution, usually in #MeToo-themed articles. It’s a strange image, though, because in no version of the original myth does anyone object to what Medusa is saying.

Here’s the logic behind the symbol, which is used by a different sort of feminists: not academic ones, but activists. For them, Medusa’s beheading represents a deadly threat against a “monstrous” and “unnatural” woman; it is an unsubtle warning to those who oppose the “hero’s” purposes to sit down and shut up.

Elizabeth Johnston makes this connection in her article for The Atlantic, using an example of dialogue from the 2010 film adaptation of Clash of the Titans when Perseus is rallying his men before they go in to confront Medusa, making sure his gang also saw Medusa as their problem and not only his.

“I know we’re all afraid. But my father told me: Someday, someone was gonna have to take a stand. Someday, someone was gonna have to say enough! This could be that day. Trust your senses. And don't look this bitch in the eye.” In the film, Perseus knows Medusa has been raped, but she’s nonetheless treated with indifference by the plot, and with hostility by the other characters.

Another recent application of the mytheme was prior to the 2016 American presidential election, when both Hillary Clinton's detractors and her supporters saw in Medusa the image of a powerful woman who was considered “nasty.” (As I mentioned in the context of honor killings, a rape victim is “nasty” to the men who think she has degraded their status.) While I am not aware of H.R.C. having been involved in advocacy for rape and abuse survivors, she certainly has been associated with a kind of dangerous female corruption by misogynistic critics.

This particular piece of campaign swag is not the only image in this genre that specifically refers to H.R.C., but it’s the one that’s most germane to my topic.8

Elizabeth Johnston points out that many other influential figures have been photoshopped with snaky hair. She mentions Martha Stewart, Condoleezza Rice, Madonna, Nancy Pelosi, Oprah Winfrey, and Angela Merkel, and suggests that readers try Google Image searches on other famous women’s names with “Medusa.”

These businesswomen, politicians, activists, and artists made the same “mistake” that Susan B. Anthony identified when she commented on the lack of women’s voices in 19th-century newspapers: “Women … must echo the sentiment of these men. And if they do not do that, their heads are cut off.” These women infringed upon the domain of men. The only response, as suggested by their Medusa-fied images? To cut their heads off; to silence them.

Another famous woman who lost her head was Marie Antoinette. This anonymous illustration titled Les deux ne font qu'un (The Two Are But One) shows Louis XVI with a pig’s body and a cuckold’s horns and Marie Antoinette as Medusa with a hyena’s body.

The association between Medusa and powerful women wasn’t always personal — it could also be applied in a general way against women’s ambitions for more political empowerment. Here, we see Medusa used to symbolize all feminist aspirations in this 1792 caricature by the English artist Thomas Rowlandson titled The Contrast. Similar imagery would later be used in anti-suffrage postcards.

If you’ve seen a few of these images, you’ve essentially seen them all … And if you ask me, one of Medusa’s finest recent cultural moments was her embodiment in Luciano Garbati’s now-famous statue. Chloe Waugh shares a wonderful ekphrasis in The Palatinate. She describes the imposing form of the statue

easily commanding any room she is placed in, and invoking a sense of power. Garbati’s statue not only reminds the viewer of Medusa’s tragic origin, but also of her humanity. Unlike many artistic depictions, Garbati’s Medusa shows no other signs of being inhuman than the tame serpents in place of hair. No hideous face, no wild mess of terrifying snakes wildly protruding from her scalp. Her completely naked body looks like that of an ordinary woman. Not only does her physical appearance remind us of the humanity within this monster, but the fact that she has clearly decapitated Perseus, as opposed to turning him to stone, shows her using human means of fighting rather than utilizing her inhuman powers. Garbati reminds us in every detail of his work that this monster is human as well, one who was wronged and sought redemption.

I like this photograph of Garbati’s Medusa (2008) better than any others, because it shows the larger-than-life figure stalking through a real space — a gallery — rather than abstracted against a black background. This was one of the images selected by the artist for his own web presentation of the work. Remember that she is seven feet tall, which would make a very imposing impression on anyone approaching her. (Even if you, yourself, are seven feet tall, facing this figure holding a sword and a man’s severed head, who looks like she has no time for anyone’s nonsense must be pretty intense.)

Garbati’s work is a deliberate inversion of Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus With the Head of Medusa (1545-1554), which we saw above as adapted by Donald Trump’s PR team. By contrast with Cellini’s Perseus, Garbati’s Medusa has no magical accessories (other than her gaze). Her sword hangs down by her side, and she looks glad to have accomplished a dirty job, but the severed head in her hands is not a trophy.

Detail of Cellini’s statue. Perseus is standing atop Medusa’s decapitated corpse, which spurts gore out of its neck.

And it gets even better: Garbati’s statue was temporarily installed across the street from the Manhattan court where the disgraced film executive Harvey Weinstein stood trial. The artist wrote on Instagram: “The place chosen is not accidental, since there they judge cases for crimes related to violence against women. We are already in the final stage working on the last details of this sculpture that became a symbol of justice for many women.” Images of his statue were widely shared online in the wake of the exposure of Weinstein’s crimes against women and the emergence of the #MeToo movement. In 2018, an image of the statue circulated on social media captioned with “Be grateful we only want equality and not payback.”

Some critics have quibbled that a more fitting payback would have been an image of Medusa decapitating her rapist; however, since the culprit was Poseidon, this would deny the Olympian god’s immortality. Shit, as they say, flows downhill (from Mt. Olympus): Olympians can punish Titans like Atlas and Prometheus, but they aren’t subject to justice from anyone beneath them. Others say that since #MeToo was initiated by Black women, an artwork depicting a European myth that was created by a European male sculptor isn’t a fitting representation of the cause. And there are also critics who object to the nudity — because some Americans are tedious Puritans.

Nevertheless, it’s also important to bear in mind that the story about the rape was not originally Greek, but Roman, via Ovid, and reflects this author’s and this culture’s preoccupations.

The Gorgon’s glow-up

Medusa wasn’t always a cursed beauty, rape victim, or femme fatale.

Hesiod is the earliest preserved literary source that mentions her. In his Theogony, which was composed sometime around 730-700 BCE, he tells an idyllic, PG version of the Gorgon’s tale:

Medusa who suffered a woeful fate: she was mortal, but the two [her sisters] were undying and grew not old. With her lay the Dark-haired One [Poseidon] in a soft meadow amid spring flowers …

He doesn’t say that Medusa was beautiful or ugly, but everyone already knew what Gorgons are, because their very name comes from the Greek gorgós, meaning grim, fierce, terrible, or dreadful, and everyone knew what they looked like from artwork and craft products. Per Wiktionary, Gorgon possibly arose “from the same root as the Sanskrit word "garğ" (गर्जन), which is defined as a guttural sound, similar to the growling of a beast, thus possibly originating as an onomatopoeia.” There is also a fascinating alternative theory which relates to underground chambers and treasure.9

Another early source on Medusa is Stasinus, and Hegesias of Aegina, Cypria, mentions some similar points to Hesiod’s in Fragment 21 (written sometime between the seventh or sixth century BCE), adding that the Gorgons were “fearful monsters who lived in Sarpedon, a rocky island in deep-eddying Oceanus.” (Source of these quotes.) Medusa is not named in this text; nor is she named in Homer’s Iliad or Odyssey; these sources only refer to the fearful Gorgon head borne on the aegis (shield) carried by Zeus or Agamemnon. The Trojan prince Hektor also seemed to have a Gorgon shield (Gorgoneion — a subject I’ll discuss more in the second article.)

So, as I said, everyone in ancient Greece knew what Gorgons looked like: besides wings, they had brazen claws, boar tusks, and skin covered with scales and/or hair. Their nostrils flared, their tongues lolled out, and their eyes were wide and terrifying. They also often had a beard.10 Snakes for hair? Not so much. Her snake-over was probably a later syncretism that drew from more ancient and also neighboring cultures.

When Pindar was writing his odes (ca 500 BCE), the serpents had become an attribute of all three Gorgons and not only of Medusa. However, she is still always the one who gets beheaded, as the other two were immortal.

Etruscan terracotta Gorgoneion antefix (6th century BCE).

Guess who these Gorgons resemble? Loathly ladies!

From Briana Saussy’s retelling of the Tale of Sir Gawain and Lady Ragnelle

“Not exactly a wild boar, not exactly a bear, not exactly a wolf, but somehow all three and more. The figure [Ragnelle] stood before them, hugely tall with runny yellow eyes and sharp white tusks, pointed teeth, red lips, and a long pink tongue that lolled out to one side of her mouth … A thin line of drool fell from the creature’s maw onto her hairy bosom, and she snuffled, snorted, and spoke with some difficulty through her tusks and teeth … “

Later, Saussy speaks of Ragnelle’s “black bristly hairs and hard claws.”

While Ragnelle was able to transform at a whim, Medusa’s glow-up in Greek arts and letters took a long time, and it went in stages.

The first stage (Archaic), shows Gorgons with every fearsome feature exaggerated.

Not the earliest known depiction of Elmo, I swear! This is the Etruscan-Corinthian Cotyla cup with an image of the Gorgon Medusa, dated to around the beginning of the 6th century BCE. I’m curious about the doglike figure on the left side.

In the Archaic era there are also many running Gorgon figures, which have similarities with much older styles of artistic representation, such as this cylinder seal that depicts Gilgamesh and Enkidu killing Humbaba (1000-700 BCE).

Doomed running monster legs …

Kylix with a Gorgon, attributed to the C painter (ca 575 BCE). Don’t try to tell me the “beard” in this image is just a fatal neck wound!

Running Gorgon, bronze (ca 540 BCE)

This is the modern flag of Sicily: it features a trinacria (the three-legged triskelion)11 with a Gorgoneion shield in the center, based on the design of an ancient coin from about 300 BCE. The wheat, too, is significant — it represents the fertility of the land. How were Gorgons associated with that? I don’t know. Maybe it’s meaningful; maybe it’s just a few symbols collected together.

The second (transitional) stage in Medusa’s glow-up has overlaps with the first and third stages. We can see that her terrifying features such as tusks and bulging eyes are still present. However, the tusks have shrunk down to fangs, and her face looks softer and more feminine. The beard also disappears. She’s not quite human, but she’s not completely other either.

Terracotta antefix (transitional period, 2nd half of 5th c. BCE)

Gold Gorgoneion pendant (transitional, ca 450 BCE). A few details, such an an earring, some of her teeth and hair, and the original enameling have been lost.

Terracotta two-handled vase (late 4th—early 3rd century BCE)

By the time the Roman Empire was established, Medusa’s face was almost indistinguishable from a normal woman’s or goddess’s — except, of course, for her distinctive snakes, and sometimes tiny wings, which are affixed to her crown instead of her shoulders as they were in the Archaic period. (These mini-wings would be a lot less effective for flight, unless she managed it purely by magic. It’s a mere polite suggestion, a nod to convention, and not a threat of swift violence.)

Chariot pole finial with the head of Medusa (detail). Roman, Imperial (1st–2nd century CE), bronze, silver, and copper.

Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Kiki Karoglou, who organized the (2018) exhibition Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art, observed that

a similar transformation is observed simultaneously in the representations of other mythical female hybrid half-human creatures, such as the Sphinxes, the Sirens and the sea monster Scylla. The differentiated iconographic rendering of these inherently terrifying symbols of death and the Underworld, believed to have apotropaic (protective) powers, was the result of idealistic humanism in Classical Greek art (480-323 BCE). Hybrid semi-human beings, however, continued to evolve in form and semantics after the classical period, and many continue to influence modern culture and artistic imagination. 12

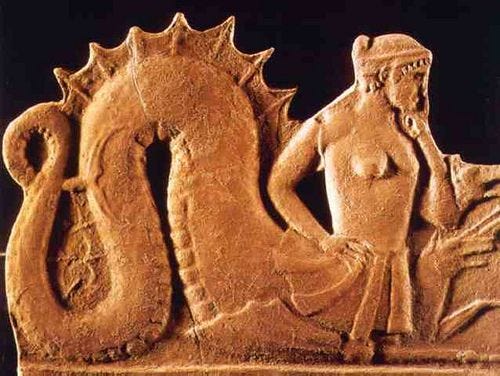

Scylla depicted in a terracotta relief from Melos. The original was “borrowed” by the British Museum, and the image was borrowed from Peter's gallery dedicated to Scylla on Flickr.

I contend that the sexual aspect was present the entire time in the form of the snakes. But being sexual and sexy aren’t the same thing, so there are differing proportions of desire and horror presented in the Gorgon’s visage. Or, to put it in Otto’s terms, of mysterium fascinans and mysterium tremendum.

While Elizabeth Johnston focused on the way powerful women are mocked using Medusa’s image, this GQ magazine cover is celebrating Rhianna’s seductive beauty, as have many other representations.

While snakes are often considered a phallic symbol in the West, this watercolor by Carlos Schwabe (1895) makes a connection that I believe most will interpret as I do:

In case the point remains obscure, please enjoy this more realistic photograph of the inside of a snake’s mouth:

Subtle, innit? The cycle of life and death, the ouroboros, all that … Medusa multiplies this image to the point where it becomes overwhelming, and even petrifying. She certainly got men hard!

Besides having many snake goddesses, Neolithic religion often made womb/tomb associations, which we can reconstruct from star myths and from elements built into their sacred monuments and burial chambers. I deal with the latter subject at some length in The White Deer,13 but do not wish to pursue it any further here.

Like a writhing pit of snakes: Gorgon genealogy

Gorgons, like other ancient female figures (Moirae, norns, etc.), are sometimes seen as a single being (as Homer claims), and sometimes as triple (see Hesiod). In the stories where Medusa has sisters, they are named Stheno (“Strong”) and Euryale (“Far-Springer”). The Gorgons’ lineage is ambiguous: in some versions, their mother is Gaia, and their father is Phorcys. However, other sources cite Ceto and Phorcys as the Gorgons’ parents, and the Graeae as their full sisters.

Medusa was the only Gorgon who was mortal, although how two immortal parents could produce both mortal and immortal daughters isn’t easy to understand. It’s not like Titans were carrying recessive mortal genes! However, her fearsome head did possess a kind of immortality, as it did not rot, and had a very long afterlife as the Gorgoneion attached to aegis shared by gods and heroes.

Medusa makes an interesting contrast with the dragon (drakaina) Echidna, who had more snake in her physiology: she had the head and breast of a woman and a snake’s torso and tail.

Hesiod's Echidna was half beautiful maiden and half fearsome snake. Hesiod described "the goddess fierce Echidna" as a flesh eating "monster, irresistible," who was like neither "mortal men" nor "the undying gods," but was "half a nymph with glancing eyes and fair cheeks, and half again a huge snake, great and awful, with speckled skin," who "dies not nor grows old all her days." Hesiod's apparent association of the eating of raw flesh with Echidna's snake half suggests that he may have supposed that Echidna's snake half ended in a snake-head. Aristophanes (late 5th century BC), who makes her a denizen of the underworld, gives Echidna a hundred heads (presumably snake heads), matching the hundred snake heads Hesiod says her mate Typhon had.

In the Orphic account, Echidna is described as having the head of a beautiful woman with long hair and a serpent's body from the neck down. Nonnus, in his Dionysiaca, describes Echidna as being "hideous" with "horrible poison."

According to Theoi.com, the “poison” could have possibly been a plague. Their caption for the image says: “Ekhidna is equated with Python,14 and Apollon, seated on the omphalos stone, slays her with his arrows. Perhaps this represents his syncretism with the god of healing (Paian) destroying the daemon bringer of plague.

Echidna was sometimes equated with Python, "the Rotting One," a dragon born of the fetid slime left behind by the great Deluge. Both Echidna and Python — at this period of mythmaking — represented the “corruptions of the earth: rot, slime, fetid waters, illness and disease.

This Medusa, in the 1981 original version of Clash of the Titans, is kind of a mashup of the original Gorgon and Echnidna. The costume designer likely didn’t feel that a hero killing a pretty lady with snakes on her head would inspire the same degree of sympathy.

The type of kinship between Medusa and Echidna varies, depending on sources. Hesiod’s Theogony says Echidna is the offspring of Ceto and Phorcys — which makes her Medusa’s sister.

However, some readers interpret Hesiod as saying that Echidna’s mother was actually the Oceanid (sea nymph) Calliope, which would mean that Chrysaor is Echidna’s father. Who’s Chrysaor? He is a giant, and the winged horse Pegasus’ fraternal twin — both were conceived in the union between Medusa and Poseidon and they were released from their mother’s body when she was slain.

Pherecydes of Athens (5th century BCE) agrees that Echidna is the daughter of Phorcys, but declines to name her mother. In one of the Orphic sources, Echidna was the daughter of Phanes.

Later myths tell that Echidna is the daughter of the underworld river Styx, personified as a goddess. Apollodorus (ca. 180—120 BCE) wrote that the mother of monsters the offspring of Tartarus and Gaia, and her mate Typhon is her brother. In this version, she is of pure Titan origin, and not of mixed Olympian/Titan as the versions that make Medusa and Poseidon her parents and Chrysaor her father would have it. Personally, I favor a Titan origin for Echidna, because the snake goddess/dragon/worm chthonic goddess is such an ancient type. Even Hesiod says she was neither like mortal men nor the undying gods.

If the ophidian parts of a deity’s body represent their generative powers, it’s not surprising that Echidna, who was very fertile, had snakelike bottom parts. Medusa’s snakes up on top were — as I suggested above — a yonic symbol, but she was unable to give birth until they were removed from her body.

Later, we sometimes see Echidna depicted with two snaky bottoms, like Melusine. In this Renaissance interpretation, her female organs are very human and connected in a direct way with the Earth. Her children may represent a threat, but her sexuality does not.

Echidna by Pirro Ligorio (1555). It is located in the Parco dei Mostri (Monster Park) in Lazio, Italy.

In this way, Echidna is also assimilated to some Egyptian deities, which I will discuss in Medusa, Part II: It's Snakes, Baby, All the Way Down!, and to her consort Typhon.

Typhon in this black-figure hydria (ca 540-530 BCE) is looking at Zeus (on the left) who is aiming a thunderbolt at him.

Echidna and some of her children, as depicted in D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths. She looks sour because many of her little ones will be killed by heroes.

In Medusa: Part II I’ll reveal even older layers of the enigmatic Gorgon’s myths and symbols. Be sure to subscribe to In the Groves of Symbols so you won’t miss this or a forthcoming article about Medusa and Gilgamesh.

See you soon!

Melinda

This photo was taken by Sharon Quarterman (Flickr). The bronze plaque is a contemporary work by the artist Luciano Mastrolorenzi.

Some say that the annual Perseid meteor shower commemorates the time when Zeus visited Danaë in a shower of gold.

But hey, you say — they didn’t do it voluntarily. Perseus stole their shared eye and tooth so they couldn’t see or eat, and this forced them to betray their kinswoman. In Greek myths, harmless intentions, innocence, or victim status do not exonerate one. Just wait till we get to the parts about what Medusa was blamed for and what happens to her and to Perseus’ grandfather!

In some versions of the story, Perseus kills the Graeae and in some he doesn’t.

Ovid, of course, used the Roman name Minerva. Even though his version of the story of Perseus and Medusa is the most common, the name Athena appears more often in contemporary discussions. The two goddesses are not identical, despite sharing a number of features. My intention is not to imply that they are, but I also use Athena’s name more often in this article because it is more frequent in discussions of Medusa’s story.

This wasn’t all that Athena gained from Medusa’s murder: according to Pindar’s Twelfth Pythian Ode, after Athena heard Stheno and Euryale’s furious and anguished cries as they pursued their sister’s murderer, she sought to emulate their keening and invented the aulos, a double-reeded instrument.

However, that was not to be the only dark association for the aulos. Other myths tell that the satyr Marsyas either invented the aulos or picked it up after Athena threw it away because she didn’t like the way it made her cheeks puff out. The foolish satyr challenged Apollo to a musical contest, where the winner would be able to "do whatever he wanted" to the loser. The randy satyr was hoping this would lead to a sexual encounter, but Apollo was the better musician, not in that kind of mood, and quite ungracious in his victory: he celebrated by stringing the satyr up in a tree and flaying him alive. Sometimes, at least in Athens, other associations were layered onto the aulos and the lyre, generally of the Apollonian/Dionysian type we are all familiar with.

An ancient Greek party just wasn’t lit without someone playing the aulos!

Detail of a Banquet Scene, Attic red-figure cup ( ca. 460 BC–450 BCE).

For more about flutes made from bones that have prophetic powers and speak with the voices of ancestors, see the essay I wrote for the Gods and Radicals blog, which was recently unlocked:

Honor crimes are acts of violence, usually murder, but sometimes rape, battery, or other violence committed by male family members against female members who are thought to have brought dishonor upon the family. Even the perception that her actions have brought dishonor is sufficient in many cases. The violence is usually premeditated and often involves the participation of several accomplices.

Attacks may be triggered by a girl or woman refusing an arranged marriage, seeking a divorce (even from an abusive husband), having a premarital or extramarital affair or having rumors spread about such an affair, dating outside of family approval, chatting online with strangers, marriage without the bride’s father’s or brother’s approval, pursuing a relationship with someone outside their caste or religion, or attempting to change their religion.

“The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) estimates that the annual worldwide number of honour killings is as high as 5,000 women and girls, though some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) estimate as many as 20,000 honour killings annually worldwide.” Source.

However, these are still very conservative estimates. (The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Around states that 87,000 women were killed worldwide in 2017. According to the report, about 50,000 women were killed by their husbands or family members, most of them by their husbands or ex-husbands, as well as by family members, including fathers, brothers, uncles, cousins, and other close relatives. The motives for the killings were jealousy, suspicion, or a request for divorce. (Source.) Accurate statistics are difficult to obtain, for a variety of reasons ranging from the difficulty of defining what is, and is not an honor killing to complicity of local law enforcement. Sometimes, the murders are committed in public view as a warning to others not to violate local “family values.”

I haven’t read the art historian Christina Coretti’s (2011) book Cellini's Perseus and Medusa and the Loggia Dei Lanzi: Configurations of the Body of State (Art and Material Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Europe, but the blurb on Amazon is certainly intriguing:

Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus and Medusa, one of Renaissance Italy's most complex sculptures, is the subject of this study, which proposes that the statue's androgynous appearance is paradoxical. Symbolizing the male ruler overcoming a female adversary, the Perseus legitimizes patriarchal power; but the physical similarity between Cellini's characters suggests the hero rose through female agency. Dr. Corretti argues that although not a surrogate for powerful Medici women, Cellini's Medusa may have reminded viewers that Cosimo I de' Medici's power stemmed in part from maternal influence. Drawing upon a vast body of art and literature, Dr. Corretti concludes that Cellini and his contemporaries knew the Gorgon as a version of the Earth Mother, whose image is found in art for Medici women.

Elizabeth Johnston must have read it, for she tells us

Cellini believed Medusa symbolized both the threat of women’s burgeoning political power and a feminized Italy. Corretti notes that these sentiments were popularized during the Renaissance by Machiavelli who, in The Prince, alluded to the Medusa icon when he described the state as a woman “without head, without order, beaten, despoiled, torn,” desperate for a manly rescuer.

“Desperate for a manly rescuer” — now, who does that sound like? Yep — Andromeda.

An alternative hypothesis is presented by the blogger Cam Rea, who acknowledges the usual etymology of Gorgon as horrible, dreadful, etc. but also forwards an alterative etymology:

The term gorgon may have been a hypocoristic of gorgyra, which means “underground chamber” along those lines. A sixth century Samian inscription lists a gorgyra chryse. The term chryse means “golden.” Therefore, a gorgyra chryse indicates an underground chamber of gold. If correct, the gorgon’s head refers to money or coin. If one uses gargara it means “heaps, lots, plenty.” This interpretation suggests not a living creature, but a treasury.

If one takes this interpretation, Perseus comes off as a mere international commercial venture adventurer who undertook a risk involving dangerous uncertainty based on speculation in hope of profit. Thus, the head Perseus seeks is not literal, but money or coin engraved with the image of the gorgoneion. In order to procure this great wealth, Perseus headed to the market to acquire certain tools and more importantly, to make contracts in order to conduct his business in Libya.

Big, if true! :-) And it would make a very neat symmetry with the beginning of the story (in Ovid), where Danaë is visited by Zeus in the form of a shower of gold, and then locked into a trunk.

Some quibble that the ring around Medusa’s face isn’t a beard, but just dripping blood and gore. Maybe some representations of her decapitated head were intended this way, but I find it hard to accept in cases where she is still standing upright with her wings outspread and her head in its rightful place. Even the Metropolitan Museum of Art's published essay on Medusa in Ancient Greek Art describes her as having a beard.

Theories on the origin of the three legs vary: some say it was from a shield design used by Spartan warriors who used a bent leg to symbolize strength. Because of its rotational symmetry, the figure can be turned any which way but still “stand.” The Trinacria would thus symbolize not only strength, but also intransigence.

I am citing Karaglou from the wonderful research review by Anna Lazarou and Ioannis Liritzis, “Gorgoneion and Gorgon-Medusa: A Critical Research Review” in Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology. The full text can be accessed here - click the link and you can download a PDF. This overview was extremely valuable to me as I worked on this series of articles.

For more on early ophidian (snake) goddess cults in the context of loathly ladies, see Ananda Coomaraswamy’s essay “On the Loathly Bride.” I have a few reservations about this scholar’s work, though, as his approach is marked by the generalizing tendencies of mid-20th century mythologists as well as by his commitment to the universalizing “perennial philosophy.” It should be considered a starting point for more in-depth research into any of the myths he talks about.

What I found of greatest interest are Coomaraswamy’s comments on mythic archetype in the loathly lady stories being a marriage between a sun god and an earth goddess, and the detailed examples he provides for the latter’s earlier chthonic and ophidian (snakelike) aspects. This finding would certainly push the loathly lady motif back to the period when the two deity types were contending for supremacy.

Yep, that Python: the monster slain by Apollo when he took over the shrine at Delphi. (His priestesses were still called Pythia, and in English, Pythoness.) Usually, Python is considered to a male serpent daemon, but in the oldest account of this story (the Homeric Hymn to Apollo), the god kills an unnamed female serpent/dragon (drakaina), subsequently called Delphyne. Echidna and Delphyne were both half woman and half snake, and both were a “plague” (πῆμα) to men. Delphyne was Typhon’s foster-mother, and Echidna was his mate — close degrees of relation.

But there’s more, and this is, I believe also a key detail: Delphyne and Echidna were associated with Corycian Cave, a grotto on Mt. Parnassus not far from Delphi. Want to know something else interesting about this cave? Its name comes from korykos, (leather knapsack), which is the magical bag Perseus stuffed Medusa’s head into.