As many know, memento mori is Latin for “remember you must die,” but The American Heritage Dictionary also provides a second definition: “A reminder of human failures or errors.” I’m writing this article on the day of the “rapid unplanned disassembly” of Elon Musk’s Starship, so it seems like a timely reminder.

However, there will be no exploding phallic symbols on this page. Instead, we will examine how white deer can function as both kinds of memento mori — and also how it can serve as a guide to a more blessed afterlife.

This mosaic from Pompeii shared by Wikimedia shows not only a skull but also the wheel of fortune. No matter what the state of one’s health, wealth, relationships, and other worldly affairs, everything is temporary and liable to change. Life hangs by a slim thread which will one day snap, releasing the soul (butterfly). Everyone has a different lot in life and the inequalities can be vast; in this way, however, we are all equal.

A mind-stopping moment of wonder

I recently gave an interview to my friend Mark Fitzpatrick1 (a.k.a. Malachus Invernus) for his podcast The Hollow Path: Art and Magick. We conversed for about an hour, covering a range of topics, and one of his questions was whether I believe there was a primal or fundamental scene; or something we might call an ur-myth, about the white deer. I told him that encountering this animal provokes a visceral reaction: you experience a mind-stopping moment of wonder in its presence.

I first encountered a real white deer in the wild this past winter just after turning in the final piece of my book — the index — to Rhyd Wildermuth from RITONA Press. In the interest of protecting the rare animal from hunters, I cannot say more about where this took place. It happened at night when I was in a car with several friends. The driver saw the herd first, and he called out “Deer!” and slammed on the brakes.

Several of them were slowly crossing the road, and one of the does was white. She stopped right in front of the car and looked at us. We also looked at her, and then she walked over to the side of the road and bounded away after all the others had safely crossed over. I felt a breathless magic in the moment when we beheld one another. Later, I compared it with the encounter described by Ted Hughes in his 1973 poem "Roe-Deer". In the moment when a man and the deer behold one another the landscape opens up into a non-ordinary dimension:

The deer seemed to be asking Hughes for a “password or sign,” but he didn’t have it and the ordinary world reasserted itself.

These moments that stand outside of time are when you feel a touch of the Otherworld. What cultures teach about the Otherworld, who lives there, and why you might be contacted varies. But you do feel that touch when time is brought to a halt.

Encountering a white deer in the wild (as opposed to one that has been specially bred and exhibited in an enclosure) is not just an omen,2 it’s also an occasion to reflect on the fragility of life and the thinness of the threat that holds us on this side of the veil — it’s a memento mori.

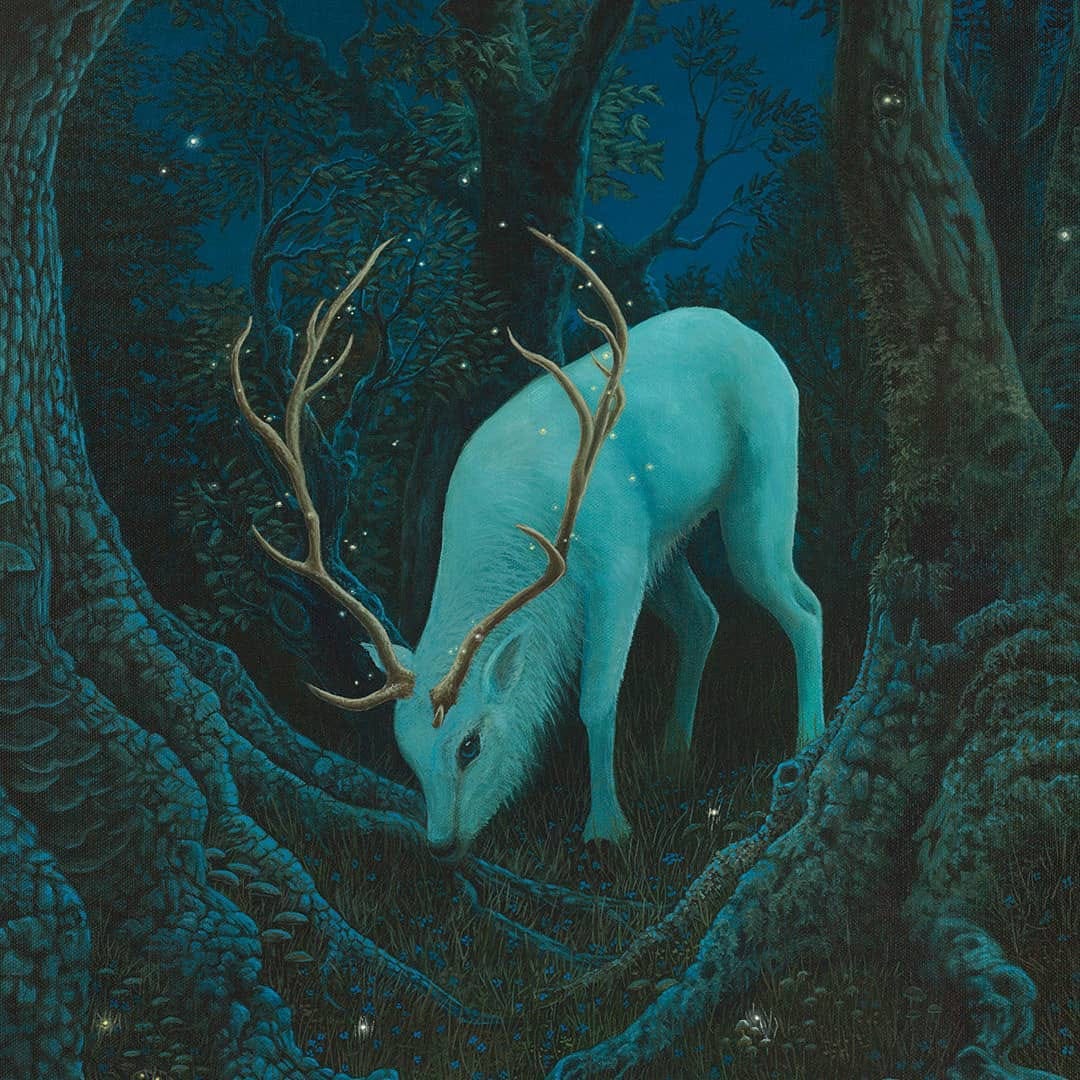

The Messenger, by Jon Carraher.

A painter’s premonitions of death:

The painter John William Waterhouse, who has been classified as a late Pre-Raphaelite and a modern classicist, was ill with cancer for the last ten years of his life. He was already gravely ill with cancer in 1915 and died from it in 1917. The canvas below, The Mystic Wood (1914-1917), is one of the last paintings he was working on. He did not manage to finish it, but it was close enough that we can see all the hallmarks of his style.

What distinguishes The Mystic Wood from other works by Waterhouse is that it lacks a historical, mythological, or literary referent. Neither the collection of figures, nor the costumes, nor any other detail suggests that he was illustrating a particular story. Rather, the pursuit of a white deer that leads figures somewhere beyond the mundane world into an Otherworld or afterlife was, itself, probably the theme. Something else that is unusual about this painting, compared with the rest of his oeuvre, is there is a boy present among the women. He seems both curious and afraid to follow the stag into the dark, deep woods.

”The two younger women are captivated and engrossed with a white stag which appears to be leading and beckoning them onwards into a forest. In Celtic mythology a white stag is often interpreted as the harbinger of death — that the Otherworld is near.”

Do you see the golden collar worn by the stag? Whose protection is he under?

Note that very little light penetrates through the thick canopy of trees to the ground, and the direction it might be coming from is indistinct, which is typical in an Otherworldly setting. The stag himself is luminous and a golden light glints off the stream in the background. What’s on the other side of the stream?

I think we find a hint of what might lie beyond the river crossing in another unfinished painting Waterhouse was working on near the end of his life, in 1916 and 1917. The Enchanted Garden illustrates a scene from Boccaccio’s Decameron. This canvas, too, was left unfinished, but it was exhibited by the Academy as a posthumous tribute to Waterhouse.

“Decameron” means ten-day event, and Boccaccio’s work was structured as a frame story about a group of young people who escaped an epidemic of bubonic plague in Florence. They left the city and sheltered in a secluded villa in the countryside for ten days. There at the villa they played a game where each day a different member of the group was chosen to be king or queen; the one who reigned that day had to tell stories to entertain their subjects, and the book contains one hundred of them.

Waterhouse’s The Enchanted Garden illustrates one of these stories. TL;DR: Ansaldo was pursuing Dianora, a married woman. Dianora agreed that she would give in to Ansaldo if he could bring forth a garden with the flowers, foliage, and fruits of May in January. A magician helps Ansaldo accomplish this, and Dianora is expected to honor her promise. However, she confesses all to her husband Gilberto. Gilberto said she had to keep to her word, but Ansaldo was touched by her honesty and releases her from the deal.

Perhaps Waterhouse was thinking about mercy and forgiveness in order to have a more easeful passing. And I believe he wanted to recreate the magic of bringing forth the lush beauty of May at the bleakest time of year during a season of illness: the endeavor of enchanting this canvas was accomplished in the shadow of fear and pain in the winter of his life.

With these two paintings, the master created both a guide and a destination for himself.

Franz Ferdinand also knew he was going to die

As I wrote in the last annotated gallery, it is said that Archduke Franz Ferdinand had shot a rare white stag in 1913. He didn’t do it on purpose — oh no! — like most Austrian hunters, he believe it was supremely bad luck to kill such an animal and that he or a member of his family would die within a year.

It’s not because he had such delicate feelings about animals; on the contrary, he spent much of his time shooting anything he could take aim at both at home and abroad, and he kept meticulous track of his kills. According to his records, he gunned down a total of 274,899 animals, many of which had been sprayed with ammunition from machine guns.

Leucism (a lack of pigment that affects the coat but not the eyes) affects 1-2% of deer3 and this nimrod bagged more than 5000 deer during his life, so it was a wonder he hadn’t hit one sooner. Most likely, he had managed to avoid shooting them by spotting them and turning his weapon aside, or he had his beaters drive them away if they appeared within his sights.

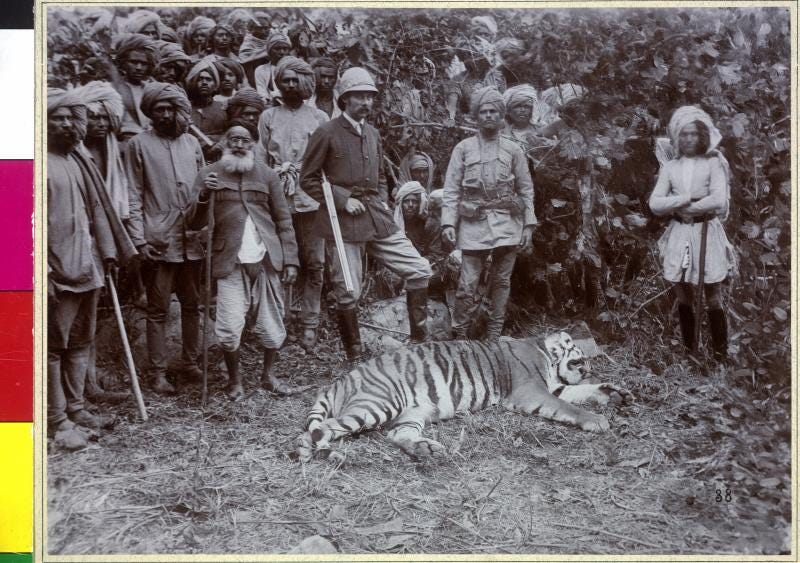

Photo from the Austrian National Archives of Franz Ferdinand posing with a tiger he just shot.

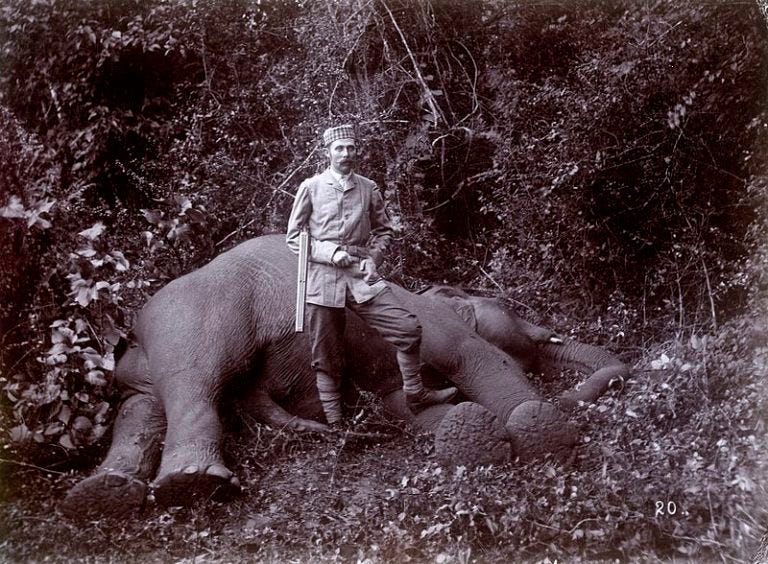

Here, FF is posing with an elephant in 1893:

Historian Mike Dash tells us that the archduke: “had spoken of premonitions of an early end, and according to one of his relatives, he had told some friends the month before Princip shot him “I know I shall soon be murdered,” while another source described him as “extremely depressed and full of forebodings” a few days before the fateful motorcade.

This illustration drawn by Achille Beltrame was on the first page of the Italian newspaper Domenica del Corriere several weeks after the event it depicts. The thick crowds in the Sarajevo streets are not shown here.

Nothing could have seemed more unlikely than the way the assassination was carried out: on June 28, 1914, the Serbian anarchist Gavrilo Princip raised his semiautomatic pistol in a jostling crowd. He had his head turned to the side and did not aim his weapon, but with only two shots — which seemed to defy any kind of probability — he managed to kill both Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie.

Princip only got lucky enough to make this second attempt on Franz Ferdinand’s life because his target wasn’t where he was supposed to be at the time. Earlier that day, the archduke had already survived a bomb that bounced off his car and exploded underneath another vehicle, injuring several of his men. He was warned to stay where he was and wait for reinforcements, but the archduke wanted to visit his injured companions in the hospital. At one point along the way, his chauffeur had to stop the car and recalculate the route. It was very unlucky that he did so only six feet away from the only person in the crowd of thousands who had murderous intentions and the means of accomplishing them.

And the rest, as we know, is history.

A white deer is a vulnerable mutant

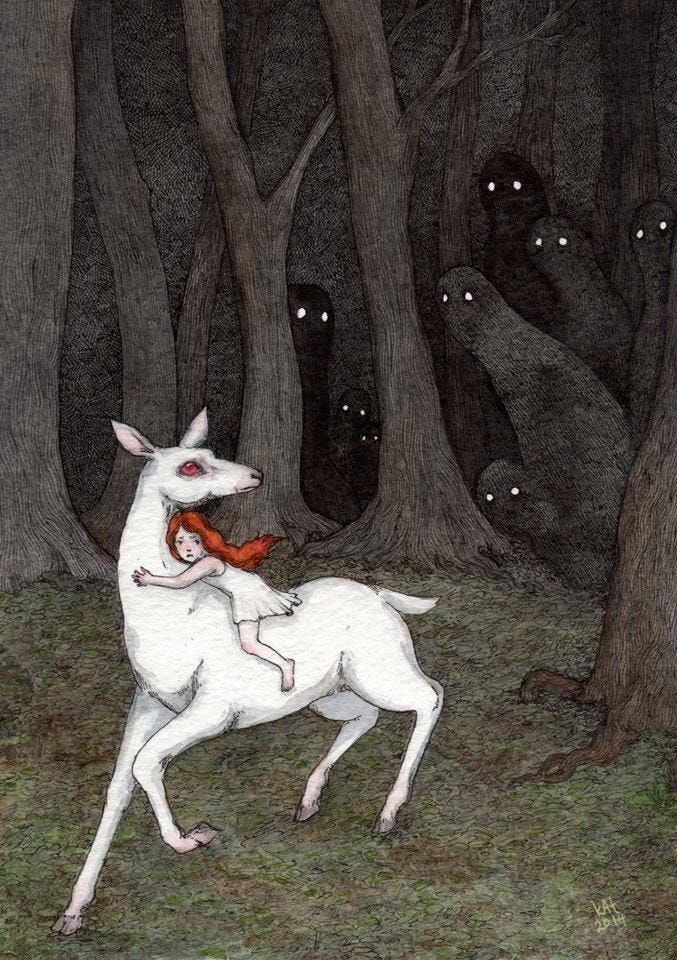

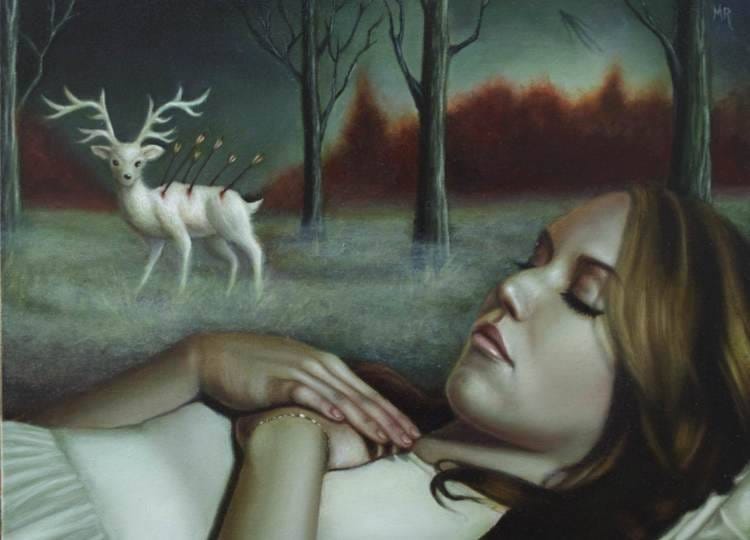

The white deer as a symbol of vulnerability in a forest filled with dangers. “There are Darker Things than Shadows in These Woods” by kAt Philbin from StupidAnimalShop on Etsy.

It is all too easy to find and kill an animal with such a bright coat: this is why white deer are sometimes called “Judas deer” — they betray the location of their herd by being so visible.

This photograph titled “Judas Deer” is by Andrew on Flickr.

In addition to their luminous pelts, white deer may have other handicaps that decrease their chances of survival, such as partial or complete blindness, deafness, or endocrine disorders. Most white fawns don’t survive their first year unless they are assisted by people in an artificially managed ecosystem. Do you remember the golden collars I discussed in my first and second annotated galleries? Their inscriptions warn humans not to touch the animal, but it would be miraculous if they prevented animal predation or the effects of genetic debility.

So the white deer is an omen of death not only for symbolic reasons, such as its color, and not only because these animals are likely to die very young. It is also an indicator of a disturbed environment: humans play a strong role in bringing these mutants to life, even if we are largely unaware of it. This is because the rare, recessive genes that create leucistic, piebald, or albino coats are more likely to propagate when there has been inbreeding, and this happens when habitat has been artificially divided in ways that prevent normal gene flow. It also may be an indicator that predator species have been suppressed. And this bodes ill for everyone. It is better not to kill the messenger.

Untitled illustration by Michael Ramstead.

Have we learned our lesson?

You’d think people would have learned something, or would have respect for white deer simply for their rare beauty, but no — when a white stag appeared in the English town of Bootle during the covid lockdowns, the authorities proclaimed that it represented a danger to them, and instead of trying harder to relocate the stag they chose violence. It’s no wonder they were plagued by toilet rats thereafter, and if that’s all they got they were lucky.

What about you?

One of the classic formulations of memento mori was Marcus Aurelius’s entry in his Meditations (which was essentially a diary).

You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.

Does reflecting on the fact that life only hangs by a thread affect what you do and say and think? What kind of experience might prompt such reflections?

Mark’s activities can also be followed on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/the_hedge_school/ ; on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/malachasivernus, on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/@malachasivernus9363 ; and on TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@thehollowpath.

The words omen and monster do not derive from the same root, but it is interesting that they have overlapping meanings. Omen has indeterminate origins and is a late arrival in the English language. According to Etymology Online, monster is derived from monstrum, which means “divine omen (especially one indicating misfortune), portent, sign.” In this sense, and if one considers death a misfortune, the white deer is a perfect example of a “monster”.

Animals that were abnormal in some way — such as those with unusual coloring — were generally regarded as omens or bearers of messages, but they did not convey just any kind of message. The etymological reason why there is the sense of a fey portent is implicit in another scion from the Indo-European root *men-. This word, *moneō, carried the meaning of “to warn” or “to advise,” as seen in the forms admoneō and praemoneō), which means the “monster” has been sent carrying a warning. I go into more depth with this and other etymologies in many footnotes in The White Deer.

True albinism is much rarer, only occurring in one deer out of about 25,000.

Really enjoying your research and insight. The writing is bright and considerate and I love your sense of humour. I’m curious and rapidly gearing towards addicted. I’ve never made so much time for a Substack read. The book will be ordered and devoured!