On permeable tapestries and legitimating landscapes (and vice versa)

In the first gallery of mystical deer, we looked at images of white stags and does that bore royal and religious meanings. Sometimes, as we saw in the depictions of St. Eustace or St. Hubert, a hunter would chase the marvelous animal and just when he thought he could kill it, he would have a moment of religious conversion or recommitment. We also examined the Wilton Diptych, which projected the ambitions of King Richard II through four pictures borne on its wooden panels. There was a complex interplay between symbols of royalty and religion, as the king showed religious figures sanctioning his right to rule and vindicating his extra prerogatives even as he had himself portrayed kneeling before them as though in humble supplication.

You may recall that the mystical white stags that appeared to the saints seemed to manifest as emergent elements of a natural order (forests, landscapes, the whole Earth) that was capacious enough to enclose human orders (religion) within it. This is a theme I’ll be getting to at the end of this article, but from another perspective.

In the images of Sts. Eustace and Hubert, the social facts of their time (i.e., the religious “truths” of the power of the crucified Jesus to speak to sinners individually; of the necessity of believing in the Christian faith; of observing its rules; and of building its physical and human infrastructure) were made evident by the emergence of a stag that proclaimed them in a human voice as right and necessary. In the case of St. Hubert, he was also given explicit instructions about a code of conduct he was expected to promulgate among hunters for the good of the animals. These huntsmen would not have come to their decisions on their own, and perhaps they could not have been swayed by clerics, but the irruption of a sacred force that came from the land itself got their attention.

(By contrast with this emergence of desired motifs from a natural landscape, King Richard’s hart bore a collar and a chain attached only to a small black hole in the painting: it was the very image of pomp and splendor, but ultimately anchored in a self-referential void.)

Tapestries were treasured in the medieval and Renaissance periods. In addition to serving as decoration, they also helped insulate cold, gloomy castles, and they had the advantage of being transportable when their owner moved around. Some showed religious themes, while others illustrated scenes from daily life. Some of the best examples of large hunting tapestries can be seen here,

including the one above: The Swan and Otter Hunt Tapestry (1430-1440).

Whatever their theme, tapestries contained rich material for edification, amusement, and whiling away long hours. Some of them featured allegorical rather than realistic or religious themes; unicorns were a popular motif. Here’s an example in the Lady and the Unicorn Tapestry, which is probably an allegory for the virtues.

There was some slippage between white deer and unicorns in legends and artwork, and I talk about that at some length in my book, but let’s get back to deer.

The winged stag was used as a personal device or emblem by King Charles VI, known first as “the Beloved,” then later as “the Mad,” and his successor, King Charles VII, continued the tradition. This wool and silk tapestry (below), a masterpiece of the Northern Renaissance style, dates from the period of Charles VII’s reign.

In the Tapestry of the Winged Deer, which was probably created in the 1450s by Jean Fouquet, we see a setting for the magical stags that is neither as wild as Hubert’s woods nor as domesticated as the patch of grass and herbs Richard’s stag is lodged in.

The tableau is set in a space that is equally natural and unnatural. The landscape is rendered in the style of the popular millefleur tapestries of the period, but the plants depicted were not just whatever happened to be growing nearby: irises and roses were both emblems used by Charles VII, and the key question posed by the picture is who is inside or outside the wattle enclosure, which must have been made by people and not animals. What we are looking at is not unchained whimsy, but layered political messaging.

(Not so) subtle hints

The scene on Charles VII’s Tapestry of the Winged Deer multiplies the winged stags, so they no longer represent only the monarch but also all those who belong to him. (Much like Richard II did with the livery badges he put on his real henchmen and on the angels painted on the diptych.) This tapestry depicts one stag lying inside an enclosure that bears the shield of the House of Valois, and two more standing outside where they must share space with restless lions prowling around the perimeter.

The middle stag bears aloft a banner with golden suns that shows Saint (or Archangel) Michael slaying a dragon, which represents an additional layer of protection and of identification with the House of Valois. The stags on the left and the right symbolize Normandy and Guyenne, territories which had been recaptured from the English at the battles of Formigny (1450) and Castillon (1453). These battles marked France’s definitive victory over England at the end of the Hundred Years’ War. The animals are wearing crowns around their necks, and the crowns hold up shields/breastplates with the Valois fleurs-de-lys on an azure background. You can see these stags would very much like to get inside the enclosure where they’ll be comfortable and protected.

The stags and lions are sorting out their affairs at distance from human society and commercial and diplomatic spheres, which are represented by the two castles at the top left and right and the ship that seems to be coming into port. So like the scenes with Eustace/Hubert, we are seeing an attempt at “naturalizing” some social arrangements by using a natural setting. With the exception of St./Archangel Michael, who is represented on a flag and is not directly present in the scene, there are no other obvious religious motifs, so the conceit here is not that Jesus or other religious figures are blessing the king or giving him. Rather, the use of this setting is a deliberate reminder of how such things work.

King Charles VII — or a patron who may have commissioned the tapestry to curry his favor — would have used the tapestry as a kind of indoor billboard for royal messaging.

Here is what the stags’ banners say:

Middle banner: Cest estandart / est une enseigne/ Qui aloial francois enseigne/ de jamais ne la bandonner/ sil ne veult son / bonneur [b pour h] donner.

Translation: “This standard is a sign which teaches a loyal Frenchman never to abandon it if he does not want to give away his happiness.”

Subtle, isn’t it?

Far left banner: Armes porte [très glo]rieuses/ Et sur toutes victorieuses. Translation: “He bears most glorious arms, victorious over all.”

Right side banner: Si noble na / dessoubz les cieulx [Je] ne pourroye /[por]ter mieulx. Translation: “So noble under the heavens I could not bear any better [meaning any better arms].”

(Many thanks to Vicki-Marie Petrick for her translations of the medieval French and her help with interpreting the symbolism.)

“Man walks within these groves of symbols each of which regards him as a familiar thing”

— Charles Baudelaire

Here’s a detail of the central stag, visually cleaned up and sold as a poster.

Take a look at the knowing glance from his very human eye, which is rather unlike a red deer’s eye with its oval pupil and lack of sclera (the white part):

It’s not really an animal lodged in the grass bearing the king’s banner: it’s a man, and he’s watching you read and react to the banner. Now guess who had light-colored eyes just like the winged stag’s? You got it! Also notice the exquisitely iridescent quality of the topmost feathers on his wings, which lends the emblem a slightly supernatural quality, just in case you were unconvinced by the rest of the messaging.

The idea of the king watching his subjects through the tapestry brings to mind the scene in Hamlet (Act III, Scene 4), where Polonius is hiding behind the arras (tapestry or curtain), which turned out to be a bad idea.

Jenhan Georges Vibert: Polonius Behind the Curtain, 1868.

But, hey now — what sorcery is this?

Did Mad King Charles cross his winged deer with a griffin? Not exactly: this illustration by Grace Owen depicts Jorge Luis Borges’ peryton, a ferocious stag-raptor he introduced in his Book of Imaginary Beings (1957). As you can see in Owen’s rendition, the peryton has the head, antlers, and forequarters of a deer and the wings and tail of a bird. Borges says it has either light blue or dark green plumage. Some artists draw perytons with four legs, while others give them only the two deer forelegs and a bird’s tail in the back.

According to Borges’ fictional fragments, perytons lived in Atlantis and escaped the destruction of the earthquake by flying away. Later, a formation of them swooped down and devastated part of Scipio’s naval forces as he approached Carthage, and the Sibyl of Erythraea foretold that the city of Rome would finally be destroyed by perytons.

We know the Romans were done in by other enemies, and let’s face it — Scipio deserved whatever he got — but why should you be concerned about perytons?

This illustration by Ivan Belikov shows a terrifying vision of the beast:

Here is where I should point out that there’s a crucial detail we can’t see in either of these illustrations: if the beast casts a human shadow, it is still on the hunt for a man to kill. A peryton could be stalking you right now, and the only way you know if it is dangerous is by examining its shadow — you might hide, but by the time it’s that close to you it’s probably too late to do anything to defend yourself, because no human weapons are effective against them.

However, perytons are not at war with humankind: each individual will kill only one victim, and after it has accomplished this its shadow takes on the same shape as its body and it is at peace.

Borges drops the hint that perytons are not beasts at all, but the spirits of those who have lost their way: “wayfarers who have died far from their home and from the care of their gods.”

This is interesting in the context of Jungian psychology, which characterized the “shadow” as the part of one’s personality that is kept unconscious because it’s socially unacceptable and/or too painful to acknowledge. In this way of thinking, the murderous monsters are not destroying the shadow, but integrating it to “win back the favour of their gods”. Here, we’ll read “gods” as “highest ideals” or “ego ideals,” because Borges does not specify any other identification for them.

This is why a peryton casting the dark shadow of a man cannot be defeated with weapons: shadows cannot be fought, caught, or escaped from. It’s kind of an image in reverse, like a photographic negative: the flying beast is the “shadow” and its shadow is the unwitting victim of the shadow’s behavior.

After the integration takes place, the creature’s shadow becomes a true image of its own form, cast by the light instead of a projection of the darkness of its own repressed human desires, instincts, weaknesses and shortcomings. It no longer feels the need to kill, nor, truly, is there anyone it could kill, since both the bloodlust and the victim are aspects of a single psyche. To wit: it has assimilated its darkest desires and become peaceful.

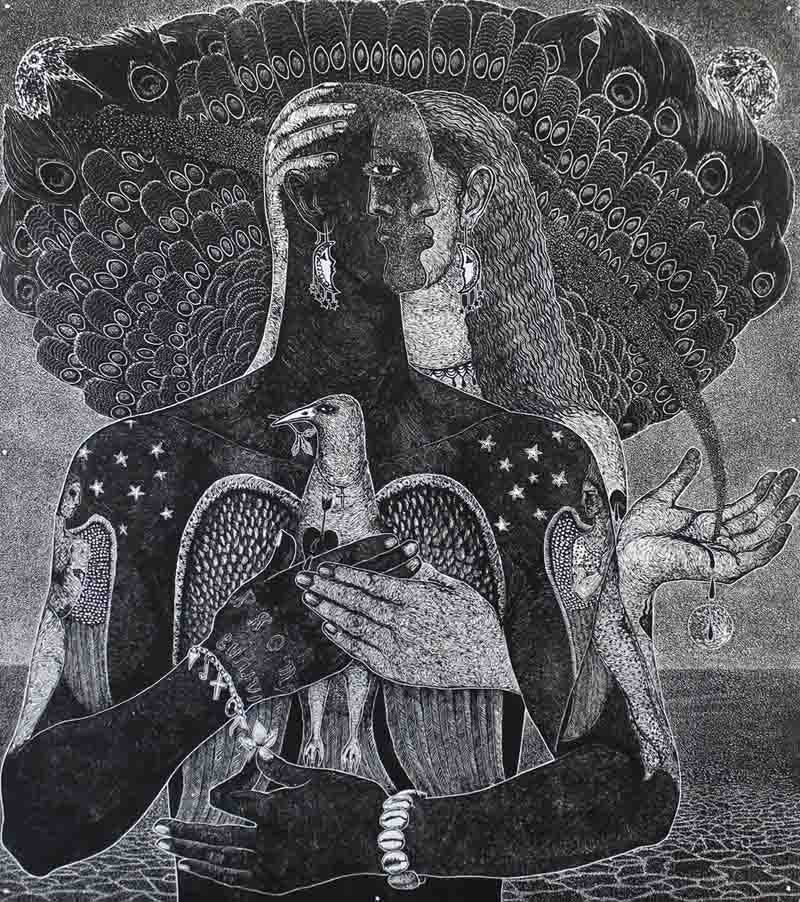

An Offer of Love, by June Carey and Ade Adesina.

Borges had read Jung carefully, and even explicitly refers to the psychologist's work in The Book of Imaginary Beings. I have not seen others refer to Jung’s theory of the shadow in connection with Borges’ peryton, but I am confident in asserting that there seems to be a relationship.

We may imagine that after integrating its shadow, a peryton can go peacefully lolloping through the woods or the clouds. Not human again, but something much more: a being equally at home on solid terra firma and in the etheric realms of ideals.

Peryton by Crow559 on DeviantArt.

Well, fine, but aren’t perytons still just a figment of Borges’ very fertile imagination? Most people seem to think so, but the Argentine poet wasn’t the only one having visions of winged stags: the owners of the Spanish Viña Muriel winery also claim a legend of a winged stag near their vineyards.

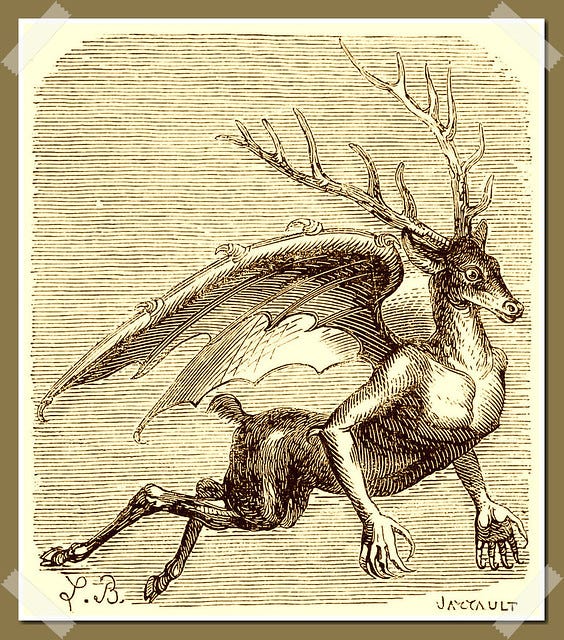

And then there’s the demon called Furfur, who was described in Johann Wier’s (1583) Pseudomonarchium daemonum:

Furfur is a great earle, appearing as an hart, with a firie taile, he lieth in everie thing, except he be brought up within a triangle; being bidden, he taketh angelicall forme, he speaketh with a hoarse voice, and willinglie maketh love betweene man and wife; he raiseth thunders and lightnings, and blasts. Where he is commanded, he answereth well, both of secret and also of divine things, and hath rule and dominion over six and twentie legions.

Here is an image of Furfur that was printed in the 1863 edition of Jacques Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire Infernal. This would be a great Halloween or Carnival costume, don’t you think?

This is Furfur’s symbol, in case you want to call him into your triangle and ask for some advice:

Whether or not Borges was drawing from Spanish legends or demon lore, his peryton very elegantly encapsulates many of the themes expressed in deer myths and legends, especially those that use white deer as bearers of fey tidings.

The white deer and the unheimlich

Allegrezza, by Stephanie Pui-Mun Law

In the chapter of The White Deer titled “Unheimlich Maneuvers,” I discuss the apparently contradictory definitions of the German word heimlich, which was used both to refer to things that are concealed and kept out of sight, such as a clandestine love affair and to “that which is familiar and congenial. Sigmund Freud remarks on the paradox:

“Thus, heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops towards an ambivalence, until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich. Unheimlich is in some way or other a sub-species of heimlich.”

However, rather than being a true contronym (a word which has opposite meanings, such as “sanction” or “cleave”), heimlich is so capacious that it contains its opposite — the unheimlich. This word is usually translated as “(the) uncanny,” and it refers to that which is only partially concealed, or rather “estranged” through the process of repression. Repressed drives or desires are then likely to come back as strange or unheimlich symbol, which seems alien but is, in fact intimately familiar — as close as our shadows.

A melanistic deer depicted by Catherine Hyde.

The thrill of meeting an uncanny apparition, whether it is a real mutant white deer that stands out brightly from its surroundings, or a vision of a peryton, gives one sensation like the chill that runs down our spine when, as the folk tradition has it, “someone is walking on our grave.”

I don’t think that the effect arises only out of the presence of extraordinary beauty. It’s also an occasion to reflect on the fragility of life and the thinness of the thread that holds us, and the vulnerable deer, on this side of the veil – a memento mori. Rather, a moment has transpired when the boundaries we usually honor between the human and nonhuman, and living and dead, are threatened, blurred, or erased. We lose our orientation in everyday life and the usual stories our culture tells and become open to something larger.

She Found her Way by Starlight; an illustration of the Grimm’s story “The Maiden Notburga and Her White Stag” by Edmund Dulac.

We may say, “sure, fine, whatever, the world is big and I contain multitudes,” but it is not enough to grasp this in the abstract. Paradoxically, it is irrational dreams or uncanny (unheimlich) visions which provide a direct guide directly into the expanded realm of the heimisch, the known-and-familiar. This process does not take place through habituation (because such apparitions are rare), but through an inspired resolution of the tension between the artificially separated pair.

Psychoanalytical theory may be backwards in a few regards (ehm! penis envy!) but, like ritual and the sacred arts, it allows space for a dance between mind, symbols, and reality. And there is a certain wyrd or magical principle mediating between them.

All beings, including us, are constituted through the interweaving of ourselves with our territories and relationships. We might call these “worlds,” and when we integrate ourselves with all of these elements, we are dreaming, while quite awake, within an enchanted realm.

Here’s an illustration of how the dance, the interweaving, works: Terri Windling cited a passage from Mary Oliver’s poem “Five AM in the Pinewoods” that expresses something of the harmony, which is found more in flow than in a steady state:

I'd seen

their hoofprints in the deep

needles and knew

they ended the long night

under the pines...I was thinking:

so this is how you swim inward,

so this is how you flow outward,

so this is how you pray.

The price of this transformation is not cheap — it is no less than the death of the old ego-forms and the release of many hopes and fears that are bound with its life in what we think is “the world,” but is in fact a prison we have constructed within it. It’s a terrifying thing to do, but so is every step that leads us toward integration with the shadow.

This is what many people call shadow work. But other words for it might also be self-reflection, self-examination, self-knowledge, or even self-love.

The feeling of the self’s separation from the world(s) that surround it is the greatest illusion, and reintegrating it is not only a work of imagination; it is also a work of love.

Beautiful World, by one of my favorite contemporary artists: Tetsuhiro Wakabayashi.

Aren’t you pulling my leg? The white deer is just an animal, right?

A beautiful leucistic doe

White deer are real animals, and it’s legal to hunt them in many places. Some biologists even argue that they should be hunted, in order to remove their flawed genes from the breeding pool. Yet there are many seasoned hunters who are not squeamish about procuring their venison believe it is very bad luck to kill a white deer. This taxidermist has made some interesting observations of how that’s worked out for those bold or foolhardy ones who try:

“I’ve mounted five true albinos in my 30 year career as a professional taxidermist. Of those five clients … three died within a year or two of the kills, one is serving a life sentence for murder and the other got divorced shortly after picking his head up and lost everything — including the house his parents gave him and all of his guns. There are a LOT of superstitions in the world and a lot of them carry some weight. This one definitely has my attention.

Here's a second, linked collection of disastrous anecdotes.

Charles VII’s tapestry seemed to watch you through a representation of the king’s own eyes. Is this mounted trophy watching over the demise of its owner, and perhaps some even greater catastrophes through its beady glass eyes?

Austrian hunters’ lore says that Archduke Franz Ferdinand had shot a white deer before he was assassinated in 1914, thus unleashing the horror of war on tens of millions of soldiers and civilians. Indirectly, we could claim this led to WWII, the rise of totalitarian states in Central Europe, and many other horrors. Franz Ferdinand didn’t shoot this deer on purpose, because believed a white deer was not only owed special protection, but actually had the power to curse him, his family, and others — and so it transpired.

Join me next time in an annotated gallery (“grove of symbols”) that will explore the fey messages borne by these animals.

The Dream Pool, by Sarah Jameson.

If you enjoyed this post or if it prompted ideas and reflections, let me know in the comments below. Is there something you’d like me to write about?

And I hope you will consider subscribing, since that gives me an idea of what kind of outreach this blog has.

Thank you for this guide through symbolic groves - your work in this piece and the preceding reminds me of two point. One is the lai of Guingamor who must hunt a white boar who leads him into Faerie, as white beasts are wont to do. The other is a tale I heard out of the backwoods of Pennsylvania some forty years back or more. Rumor spread in the country town that a white buck had been spotted in woods, and every young hunter swore he would be the one to bring it home - something about it did not put off these men but rather drew them implacably to destroy it. I do not know in anyone did succeed in this fell deed or what became of him if so - but there you go, within living memory, hunting culture proves to still be fascinated by the white deer.