Claude Lorrain (1604/5–1682) was a French painter who spent the best — and last — years of his career in Rome. The master’s last canvas, Landscape with Ascanius Shooting the Stag of Sylvia, was made for his most important patron, Prince Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna.1

This work may have been left slightly unfinished, because Lorain did not include it in his Liber Veritatas, a catalogue of his completed works.

Liber Veritatas means “Book of Truths” in translation from Latin. What do we have here, in this work that could not be included in such a volume?

Landscape with Ascanius Shooting the Stag of Sylvia, 1682. Claude Lorrain Wikimedia.

The painting depicts an episode described in Book 7 of the Aeneid. In this scene, Aeneas’ son Ascanius is taking aim at a stag — but what he doesn’t realize is this is no wild animal. The stag, which shows no fright at the sight of the hunters and their hounds, is tame, and he belongs to the royal Latian household.

Silvia, the daughter of the king’s chief ranger/gamekeeper/herdsman, is the stag’s protectress, and Ascanius’ act is going to foment a war.

In the wake of the animal’s bloodshed, Trojan and Latian forces clash over the site where Aeneas’ distant descendant Romulus would eventually found his city — and the peaceful landscape depicted here would never be the same again. Great trials and difficulties had been foretold by the Cumaean Sibyl in Book VI of the Aeneid, and Lorrain foreshadows the impending conflict in the storm clouds on the right, and in the wind bending the trees on the left.

Here are the relevant lines from Virgil’s epic:

Hades’s Virgin [the Fury Allecto]2 drove his hounds to sudden frenzy,

touching their muzzles with a familiar scent,

so that they eagerly chased down a stag: this was a prime

cause of trouble, rousing the spirits of the countrymen to war.

There was a stag of outstanding beauty, with huge antlers,

that, torn from its mother’s teats, Tyrrhus and his sons had raised,

the father being the man to whom the king’s herds submitted,

and who was trusted with managing his lands far and wide.

Silvia, their sister, training it to her commands with great care,

adorned its antlers, twining them with soft garlands, grooming

the wild creature, and bathing it in a clear spring. Tame to the hand,

and used to food from the master’s table, it wandered the woods,

and returned to the familiar threshold, by itself, however late at night.

Now while it strayed far a-field, Iulus the huntsman’s

frenzied hounds started it, by chance, as it moved

downstream, escaping the heat by the grassy banks.

Iulus himself inflamed also with desire for high

honours, aimed an arrow from his curved bow,

the goddess unfailingly guiding his errant hand,

and the shaft, flying with a loud hiss, pierced flank and belly.

But the wounded creature fleeing to its familiar home,

dragged itself groaning to its stall, and, bleeding, filled

the house with its cries, like a person begging for help.

Silvia, the sister, beating her arms with her hands in distress, was

the first to call for help, summoning the tough countrymen.

They arrived quickly (since a savage beast haunted the silent woods)

one with a fire-hardened stake, one with a heavy knotted staff:

anger made a weapon of whatever each man found

as he searched around. Tyrrhus called out his men:

since by chance he was quartering an oak by driving

wedges, he seized his axe, breathing savagely.

Then the cruel goddess, seeing the moment to do harm,

found the stable’s steep roof, and sounded the herdsmen’s

call, sending a voice from Tartarus through the twisted horn,

so that each grove shivered, and the deep woods echoed:

Diana’s distant lake at Nemi heard it: white Nar’s river,

with its sulphurous waters, heard: and the fountains of Velinus:

while anxious mothers clasped their children to their breasts.

Then the rough countrymen snatching up their weapons, gathered

more quickly, and from every side, to the noise with which

that dread trumpet sounded the call, nor were the Trojan

youth slow to open their camp, and send out help to Ascanius.

The lines were deployed. They no longer competed

with solid staffs, and fire-hardened stakes, in a rustic quarrel,

but fought it out with double-edged blades, and a dark crop

of naked swords bristled far and wide: bronze shone

struck by the sun, and hurled its light up to the clouds:

as when a wave begins to whiten at the wind’s first breath,

and the sea swells little by little, and raises higher waves,

then surges to heaven out of its profoundest depths.

Book VII, verses 479-818, cited from Poetry in Translation.

The Vergilius Romanus is one of the few surviving manuscripts from the classical era. This 5th-century illustrated manuscript contains Virgil’s Aeneid, Georgics, and some of the Eclogues. This scene, of course, depicts the hostilities that ensured after Silvia’s stag was fatally wounded. Wikimedia

The Silvii

According to Roman origin myths, Rhea Silvia, a distant descendant of Aeneas and Ascanius was the biological mother of Romulus and Remus. Their foster mother was Acca Larentia,3 who was a semi-chthonic deity of ancient Etruscan, somewhat obscure origins. Her name may etymologically identify her status as the mother of the Lares (tutelary daimones who were also involved with household prosperity), and she is credited as the mother of the Roman Arval Brethren [Fratres Arvales], a college of priests who organized public rites for the Lares. Sometimes, Acca Larentia was depicted (e.g., by Livy) as a mortal woman who was either a former prostitute, or promiscuous. Acca Larentia’s husband, Faustulus, was a shepherd — an ordinary human being.

The other element in the story of the miraculous twins’ infancy was Lupa, the she-wolf. However, this was a term used to describe women in the oldest profession, so there is a blurring between the human and animal, and a mythical figure could be both at the same time if we consider that the wolf was an ancient totem of the Romans’ ancestors, and it was deeply integrated into their myths and rituals. To wit: a man or woman who was deeply identified with this totem animal was, for mythic and ritual purposes, a kind of wolf. The kind of human wolf who embodies the virtues of both species, rather than their vices (i.e. a werewolf).

The Capitoline Wolf statue has long been a symbol of Rome’s mythic identity. A 5th- or 6th-century BCE origin has been attributed to it, but this is extremely unlikely. Certainly, the infants were made and installed sometime between the 13th and 15th centuries CE. Wikimedia.

Rhea Silvia was a princess of the Silvian Dynasty and a priestess of Vesta who fell on hard times after her uncle Amulius deposed her father, King Numitor. The usurper also killed her brother, Aegestus (Egestus), who was the legitimate heir to the throne. Rhea was forced by her uncle to serve Vesta and maintain chastity so that no heir from Numitor’s line could be born and threaten his reign. However, she was raped by the god Mars, and conceived twins.

Rhea Silvia (1414), by Jacopo della Quercia. Wikimedia. These babies look a little too lively and hefty to put into a floating basket, but the legends tell that soon after Romulus and Remus were born, the desperate mother placed her sons into a basket and set them adrift in the Tiber River, leaving them to the mercies of fateful powers.

This is a pattern that had already iterated in previous generations of Silvii: descendants of the line seem to find their way to safety from wild places. In Debra May Macleod’s retelling in the novel Rhea Silvia (2022)

As the band of desperate [Trojan] refugees moved through the woods day after day, it fell upon the young Ascanius to keep the embers alive. Having nothing more than the clothes on his back, he asked the spirit of the woods, Silvanus, for guidance. Silvanus inspired him to use his surroundings — the trees, the moss and lichen, the grass — to preserve the embers and keep them aglow during their harrowing journey. That is how he was able to bring the Iliaci ignes Vestae, the Trojan fires of Vesta, to the city of Lavinium in Latium.

When Ascanius became a man he taught his wife how to keep the embers alight, and together they traveled to found Alba Longa, bringing the goddess’ eternal flame with them and keeping the Trojan flames alive in their new city. And when Ascanius became a father, he named his firstborn Silvius in honor of the spirit and the woods that had nourished that fire. Thus, the Silvian dynasty was born.

An alternate version retold by Dionysius claims that Silvius was not the son of Ascanius, but of his half-brother: his parents were Aeneas and Lavinia. Lavinia was afraid that Ascanius might be tempted to harm her or her child because they could challenge his right to the throne. She therefore hid in the woods, and was sheltered by Tyrrhenus, who, in this version, was a swineherd and friend of her royal father, Latinus. She and her son emerged from the woods when the Latins accused Ascanius of having killed his stepmother. Dionysus says that Silvius then became king of the Latins instead of Ascanius’ son Iulus, who became the ancestor of the Julii.

Fateful, fey deer

In Virgil’s text, Silvia’s name indicates that she isn’t just any girl, but should be associated with the lineage of Alban kings (even if indirectly, as a retainer’s daughter). Virgil does not mention the stag’s color, but the motif of extraordinary deer that are white and under royal or divine protection is ancient, widespread, and always carries profound meaning where it appears.

A deer that bears an fateful message often appears and is killed by the heir of a kingdom (empire); a man who should have known better. This is what Austrian legends tell about Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who allegedly shot a white stag in 1913 ….

My book, The White Deer: Ecospirituality and the Mythic, explores the motif back to its earliest origins, interprets the message this fey animal brings, and suggests where humanity has erred in ways that invoke such uncanny omens.

As if to add emphasis Silvia’s stag seems to be pale-colored or white in some artworks, though not all of them. This is not the case in the Rubens (below), but the deer in the Vergilius Romanus, which is 1100 years older, seems to depict a pale animal. I asked a friend, who teaches conservation of old documents and manuscripts about the pigments, and she said that brown pigments tend to be stable, and do not usually lighten over time. She cannot provide an expert analysis on the basis of reproductions displayed on screens, but, in her opinion, the deer was probably painted with a light-colored pigment.

The Death of Silvia’s Stag. Oil sketch by Peter Paul Rubens, ca. 1638. Kept in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

A cyclical memento mori

Besides the uncommon theme for a painting,4 something else that is noteworthy about Lorrain’s last work is its telescopic handling of time. Corinthian columns still marking the site of a ruined temple was an anachronism. Romans in the late Republic believed that their city was founded by Romulus sometime around 750 BCE, which predates the emergence of the classical orders by several hundred years.5

In the 17th century, classical ruins were understood by viewers of artworks as a token of the glory of times past. In this sense, they were the visual equivalent of “once upon a time” at the beginning of a fairy tale: they were an easily-recognized element that ushered viewers into a narrative taken from events in the misty, mythic past.

However, for Corinthian columns additionally set an elegiac mood, because they referred to the death of a betrothed maiden.6 As I have mentioned above, both Virgil’s text and Lorrain’s painting are rife with imagery that refers to ideas of virginity (a state ripe with vitality and potential) and death.

We, as the viewers know something of Rome’s mythic history. Virgil also indulged in extensive laudation of Rom’s future glory (especially in relation to the Caesars) in his account of Aeneas’ trip to the underworld. From the epic poet’s perspective, he was living at the high point of history, in an empire that had conquered the known world and was enjoying a Golden Age.

However, viewers in both the 17th century and in our own time know that after Rome’s spectacular period of expansion, it would “fall,” leaving us to play with its shades among the glorious ruins.

In the words of the English art historian Sir Ellis Kirkham Waterhouse, the painting thus “embraces the whole trajectory of Roman civilization across history, from its start to its end, and peoples an idealized landscape from Claude's time with figures from its early history.”7

Speaking of people whose name is Waterhouse (though I don’t believe they are related), in “The White Deer as Memento Mori,” I discuss and interpret the white deer John Williams Waterhouse painted on a canvas he was working on during his final, fading years. Waterhouse’s The Mystic Wood lacks an explicit literary or mythological referent, and, in my opinion, this work, and possibly also The Enchanted Garden, were created by the dying man as portals into a realm of eternal beauty.

The Mystic Wood, John Williams Waterhouse, unfinished (1914-1917). Wikimedia.

Claude Lorrain’s friend Nicolas Poussain (another Frenchman who lived in Rome and painted classical subjects, often in a picturesque “Arcadian” setting) sometimes chided Lorrain for having less knowledge of myths, art, and lore than he did. Poussain’s paintings are packed with references not only to literature, but they are a visual pastiche of motifs he lifted from other artworks.

Among Lorrain’s later admirers was Herman Melville, who owned a number of prints of his work.

Melville was aware of the tradition of comparing Lorrain with Poussin, and commented that Lorrain is “the mildest tempered swain / And eke discreetest, too may be, / That ever came out from Lorraine / To lose himself in Arcady.”

To Claude no pastime, none, nor gain

Wavering in theory’s wildering maze;

Better he likes, though sunny he,

To haunt the Arcadian woods in haze,

Intent shy charms to win or ensnare,

Beauty his Daphne, he the pursuer there. (NN BBO 154)

Melville’s “haze” distinguishes Claude’s characteristic kind of beauty from the combination of clarity and “theory” commonly attributed to his sometime sketching companion Poussin. Source of quotes and analysis.

Yet, even Poussain sometimes gave in to the drowsy lull and Arcadian haze, as we can see in Numa Pompilius and the Nymph Egeria:

Nicolas Poussain, Numa Pompilius and the Nymph Egeria, ca. 1631-33. Wikidata.

I have written about NP and Egeria in my article “Wet and Wild,” which is a survey of water nymphs and the lands they steward.

In the painting above and the one below: Katabasis of Orpheus,8 the subject lent itself to a more dreamlike atmosphere that couldn’t be packed with as many details and references as he was wont to insert into his canvases.

Katabasis of Orpheus, attributed to Nicolas Poussain, undated, held in a private collection. If it is not Poussain’s work, it must have been created by an admirer of Lorrain and Poussain.

Some art historians have criticized Lorrain’s sloppy use of perspective, and his impossibly elongated figures, which were inspired by Northern Mannerism. But here, stretching the bounds of the possible is not just a virtue, but perhaps also a necessity if we are to leave the world of logos and enter the realm of mythopoetic dreams and eternal returns. “Landscape” is the first word in the work’s title,9 and Lorrain’s idyllic wooded landscapes are not only his best legacy, but a defining moment in western art history. His work was not mere decoration and repositories of motifs. If the artist’s intention was that this cyclical vortex, thickly suffused with both dread and renewal, functions as a doorway through which we exit the mundane and inhabit the space of perennial realities, it would have made a very fine destination for a soul’s onward journey.

Prince Lorenzo Colonna was an art connoisseur and collector, and Claude Lorrain produced at least nine paintings for him between 1663 and 1682, when the artist died.

The curators at the Kimbell Art Museum write: “The prince, whose family had its origins in the countryside outside of Rome, undoubtedly shared Claude’s pleasure in hilly sites such as Tivoli and Nemi, adorned with ancient temples, bridges, and other reminders of the Arcadian delights celebrated by Virgil in ancient times.” The ideal landscapes he painted later in his career were nostalgic in tone, and always incorporated classical ruins and “carefully calibrated landscape elements,” “and a cool, blue green palette and clear articulation of spacial intervals.” Link.

Allecto/Alecto, whose name means “the implacable or unceasing fury” was a Fury who was commissioned by Juno to prevent the Trojans from succeeding in establishing themselves in Latium. Like her sisters, Tisiphone and Megaera, she had snakes for hair, blood dripping from her eyes, and the wings of bats. (Faithfulness to all these details may vary in artistic representations.)

Juno, Seated on a Golden Throne, Asks Alecto to Confuse the Trojans (Aeneid, Book VI). By Master of the Aeneid in Limoges, France, ca 1530-35. Public domain image from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is one of at least 80 enameled images that illustrated Virgil’s epic. According to the Met’s catalogue, these scenes are copied from woodcut illustrations produced for an edition of the Aeneid that was printed by Johann Grüninger in Strasbourg in 1502 and/or in an edition published in Lyon in 1517.

I love Alecto’s dress, her snaky hair, and the way she gracefully flutters up and away from the fire and brimstone spewing from the maw of the chthonic hellbeast, and Juno’s all like “Please, bitch — not in my throne room!”

(If you like pictures of women with snakes on their heads, you will love my articles on Medusa: Part I and Part II.)

It is also interesting how the mural crown is neither quite sitting atop Juno’s head nor is it clearly a carved relief in the throne. It’s as if the artist couldn’t decide which was more appropriate for a female ruling power. Certainly, Juno’s nudity does not suggest a regal role — in this aspect, the depiction sets her beyond ordinary human laws, even those that the political order of the gods were modeled upon. But this transcendent power of presence is then undermined by the star covering up her lady parts.

I wrote a short story titled “Lupercalia” that interweaves some of the lore of Acca Larentia with fictious contemporary characters. It is set in a cabin in Central Bohemia in February, 2020, just before the outbreak of covid was officially announced in the Czech Republic.

I’ll eventually share it here. But I not before putting a few more nonfiction articles up, because I’m a little concerned that readers who come here for the illustrated essays might take fright and leave if the fiction seems like it’s taking over.

This is a dead link that comes up in searches on multiple browsers and connects to the home page of the auction site Catawiki, saying that the link is a year old. Conclusion: one year ago, they probably sold this picture titled “Ascanius Hunting the Pet Stag of Silvia” and identified as the work of a “17th-century Italian artist.” Note: while the use of shading isn’t particularly masterful here, it’s at least possible that the stag was supposed to be white.

Furthermore, the city of Troy, the original home of Aeneas and Ascanius was famous for its high walls and puissant defensive structure, and not for its fine marble columns. You can see some visualization of the city here.

If Lorrain had intended to refer to the pre-”Trojan” cultures, he could have used the Tuscan order, which reflected column shapes that date in the Italian Peninsula at least back to the Etruscan period. However, the use of the Corinthian columns reinforces a “Greek” (Trojan) past, no matter that Troy looked quite different, and the later Roman adoption of this style.

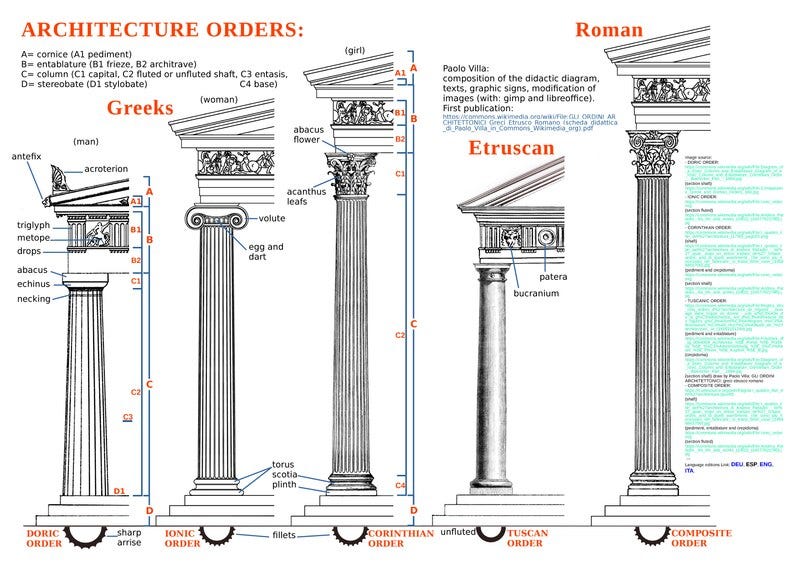

Architecture Orders: (Doric Ionic Corinthian Tuscan Composite), by Paolo Villa. Wikimedia.

The art historian George L. Hersey writes about the last myth Vitruvius related in De Architectura about the orders of columns in his article “Vitruvius and the Origins of the Orders: Sacrifice and Taboo and in Greek Architectural Myth”. For Vitruvius, columns always represented human bodies: male, in the case of the Doric order; matrons, in the case of the Ionic; and maidens, in the case of the Corinthian order.

The Roman author attributed the Corinthian order’s origin to a myth about how the architect Callimachus happened upon the tomb of a Corinthian girl who was betrothed and died before her wedding. The tomb was decorated with a basket containing the girl’s collection of goblets, and there was a flat tile laid on top of the basket to hold everything in place. An acanthus plant grew up from the base of the basket, with its foliage bursting forth from below. (Why goblets? Was collecting such things a popular hobby at that time? Or was she a priestess who served sacramental drinks?) Anyway, according to Vitruvius, after time passed, an acanthus plant grew up from the base of the basket, its tendrils curling toward the tile. Acanthus, in Greek and Roman culture, was often associated with grief, mourning, and the hope of a kind of resurrection. Callimachus, touched by this scene, translated it into the flourishes that were added to the older Doric and Ionic orders, thus creating the Corinthian.

An engraver’s visualization of the origin of Corinthian capitals. Source: NY Public Library Digital Collections.

Hersey comments: “Like the Doric, Caryatid, and Persian columns, the Corinthian is a memorial to the dead. There is a sort of plot to Vitruvius' five tales. The first three types of column mark Greek victories, the expulsion of Eastern invaders, and then the establishment of Greek colonies in the East. The appearance of the Ionic is a turning point. It marks the end of the period of war and, with its linking of male and female, suggests a marriage, one that in fact results in a Corinthian daughter. This daughter, like all the other orders, possesses a specific human physique or costume: Vitruvius says it has the physique of a young girl, which suggests not only that it is the daughter of Doric and Ionic but a personification of the original Corinthian maiden. Furthermore, her death before marriage-of which Vitruvius makes a point-prevents new offspring.

That is, in terms of the five myths, the girl's death prevents the birth of new types of column. The pattern of the tales is complete."

Here, the ruined Corinthian columns, which — as Vitruvius and Hersey have explained — refer not only to death, but also to maidenhood and a lack of future generations has a particular resonance with founding myths of Rome (Rhea Silvia and the establishment of the order of childless Vestal Virgins).

In my opinion, Lorrain was using these columns not only to refer to the pomp and splendor of Rome itself, and to its downfall, but as an explicit memento mori and a reference to the “virgin” figures who held up not only stone pediments but also the deeper mytho-symbolic and social structures of Rome.

I have written a lot more about Caryatids, and you will be able to read this work under the publishing auspices of Sul Books in the near future.

In Piper, David, ed. Enjoying Paintings. Baltimore Penguin, 1964. p. 207.

Katabasis of Orpheus is a painting in the private collection of my friend Ethan del Carmen. He has had it analyzed by art experts (analysis available for view here), but it has not been adopted into Poussain’s canonical oeuvre.

(What’s a “katabasis”? It’s a journey or soujourn in the underworld, which is normally forbidden. In other words, this is a scene depicting Orpheus crossing over into the realm of Hades.)

Many of Lorrain’s works have “Landscape” in their title, and even when they don’t, the human figures — which “elevated” them into the more prestigious and lucrative genre of history painting — seem more like an excuse for the artist to immerse himself in living light contained within rather mineral-like foliage (the thing that I always most adored in Lorrain’s paintings) and Italian scenes that he makes any viewer feel welcome within, as if finally coming home to holy ancestral ground.

Here is a WikiArt gallery of all his known paintings that allows you to get an overview at a glance.

Thank you. The Vergilius Romanus is a wonderful survival!

Melinda- It's been a minute since I revisited Aenid. This piece is a great reminder of its vast world and implications. Hope you're well this week. Cheers, -Thalia