Acca Larentia is a mysterious chthonic goddess of Etruscan origin. She features prominently in my short story "Lupercalia,” which I recently shared In the Groves of Symbols.

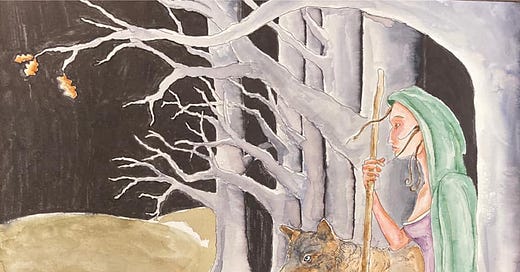

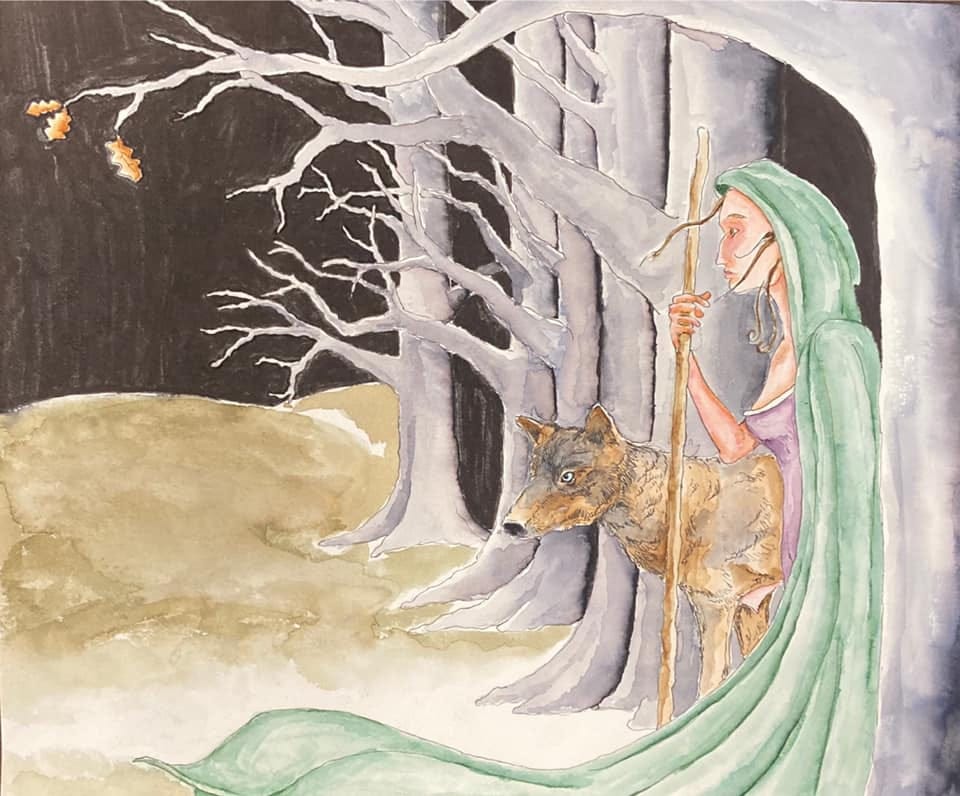

This watercolor of Acca Larentia and Lupa emerging from a forest in the moonlight was painted for me by my dear friend Jon Bolt.

Some of Acca Larentia’s stories are delightful, others are perplexing, or hard to bear. (Tales that are too easy to derive “lessons” from, and those that simply proselytize have shallow roots and and don’t bear much scrutiny or inspire much reflection.) There are myths, like those of Medusa and Elen of the Ways that branch out like rhizomes, but Acca Larentia’s stories seem to constantly loop back to a few themes, the very themes that most fascinate me: wolves, the boundaries between nature and nurture, and female self-sovereignty.

A wolf’s tail is straight (this is one of the features that distinguishes them from dogs) but these tale loop back, like a dog’s tail — a feature of its domestication. And that’s exactly what we are going to witness in these tales’ evolution.

Photo by the Wolf Conservation Center in NY State.1

These tales, however, do not only loop, but they are loopy (lupi is Latin for “wolves”).2 They remind us not only of a distant, mythical past but give us themes to ponder now: you’ll follow traces of how the female powers that stood behind family lineages were muted and humbled, and how ancestral cults were of female lines was diverted into prestige for mythic male ancestors, and how ancestral cults were replaced with civic pride. That which is wild, which doesn’t submit to domestication, is ever present in the form of the she-wolf, who, along with Acca Larentia, has been an integral part of Rome’s stories of growing into a civilization.

From loquacious to silent as the grave

A good place to begin with these stories is with a naiad whose father was the river god Almo/Almone. In Ovid’s Fasti, Almo advises his garrulous daughter not to spread gossip, but she doesn’t listen. In fact, there was no way she could help it: her name, which was originally “Lala,” came from the Greek λαλέω (“to talk, to chatter”) in imitation of babbling or blathering — she was its very personification.

The loose-tongued nymph tells Juno that her husband Jupiter is having an affair with the god Janus’ wife Juturna. Enraged, Jupiter pulls Lala/Lara's tongue out and orders Mercury to take her to the "infernal marshes" of Avernus, which is the gateway to the Underworld. As if all this weren’t bad enough, along the way, Mercury also rapes Lara, heedless of her desperate glances. This is how the now mute (Latin: muta) and silent (tacita) nymph conceives the Lares, twin guardians of crossroads and the city of Rome.

Mercury Embracing the Nymph Lara. engraving by Jan Harmenz Muller, 16th-17th c. Source.

Lara is connected with, which means she is either identical to or was assimilated to the Dea Muta (the mute goddess) and Dea Tacita (the silent goddess), aka Muta Tacita. These spirits may be variously considered as nymphs, minor goddesses, or multiple names or aspects of a single deity, but all of them are connected with the dead.

In this myth, Lara/Dea Tacita is explicitly associated with the underworld, the world of the dead because Mercury led her there. However, perhaps the association had already been present before. I’m suggesting — though I lack evidence — that this myth imposed silencing, rape, and the participation of a new cast of divine characters who represented a patristic social order onto an autochthonous female divinity, as so often happened with nymphs. But let’s move on …

The rites honoring Dea Tacita were originally held on December 23 (on the occasion of the the Larentalia, which I will describe below), which is another association (besides the etymological connections of Lara/Lares/Larentia) that connects Lara with Acca Larentia.

Later, Dea Tacita’s rites were assimilated with the Feralia in February, which was a holiday for the dead. Lara/Dea Tacita was also a good fit for the Feralia because she was silent: a silent goddess was an ideal symbol of the dead, who are characterized by eternal silence.

The proceedings at the Feralia were intended to prevent malicious gossip and slander from afflicting the people of Rome. They involved an aged woman sprinkling the head of a fish with sticky pitch, roasting it in wine, and consuming the resulting drink. The black beans create an interesting parallel with the paterfamilias’ role in the Lemuria, where they are used as a propitiatory offering used to exorcise malevolent spirits.3

This is how Ovid describes the rite in Fasti:

Behold, an old hag, sitting in the midst of girls, performs rites to the Silent Goddess (she is hardly herself silent), and with three fingers places three lumps of incense beneath the threshold where the little mouse makes his secret route. Then she binds enchanted threads with dark lead, and rolls seven black beans in her mouth. Next, a fish head, tarred and sewn up with piercing bronze needle, she roasts in a fire, dripping a little wine on it; what’s left of the wine, she and her companions drink, though she has more of it. “We have bound hostile tongues and unfriendly mouths,” she says as she leaves, and so the drunken hag exits.

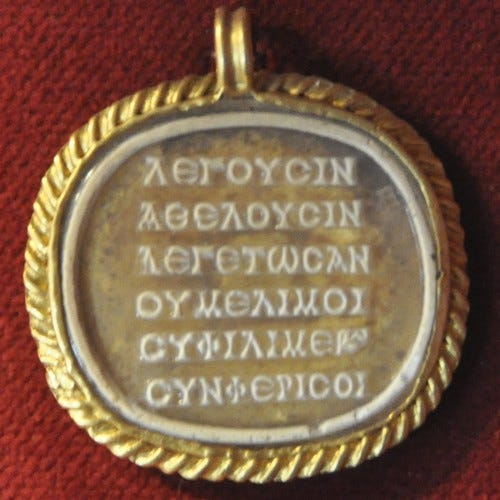

While the rite was intended to prevent the spread of gossip and slander in the city — arguably, a very prosocial purpose — Dea Tacita was also invoked in curses that aimed to bring fear, death, and obscurity upon an enemy, which are symbolized by the seemingly unimportant or poetic detail of the mouse. For example, an inscription found in Rhaetia calls for the goddesses Mutae Tacitae to kill the person the magician despised and make him to “wander, fleeing, like a mouse.”

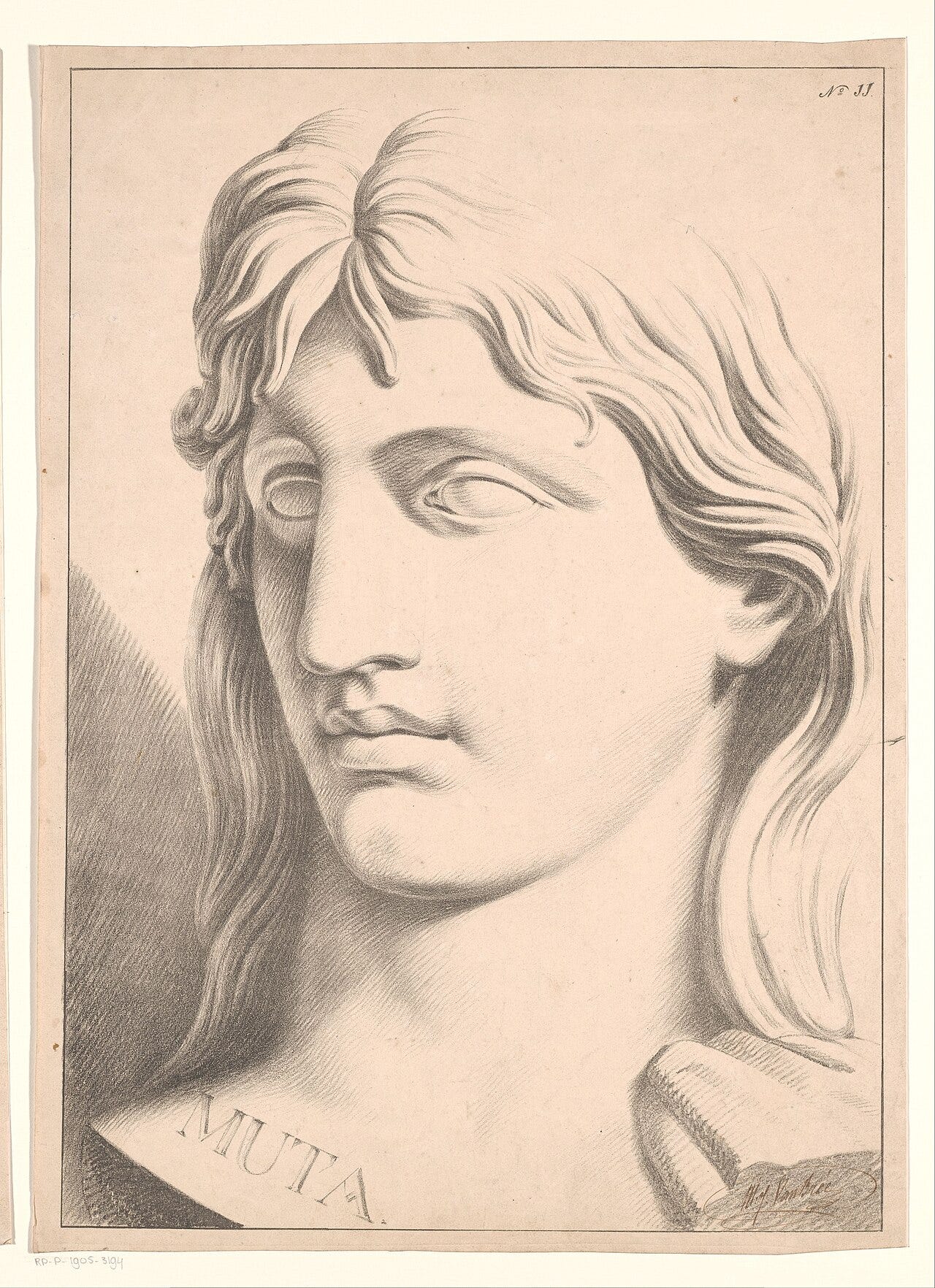

Lithograph of Buste van Lara (Dea Muta) by Mattheus Ignatius van Bree. First half of 19th century. Source: Wikimedia.

Like princess Rhea Silvia (the bio mom of Romulus and Remus whom I will discuss more below) and Acca Larentia (the twins’ foster mom), Lara/Dea Tacita was also the mother of twin boys: the Lares compitales, spirits who protected neighborhoods, city streets, and — by extension — the city itself.

Toga-clad Roman men in a fresco from a house near Pompeii. They are probably Compitalia.4 Wikimedia.

Mother of the Lares

When many think of ancient Roman religion, they first imagine larger-than-life Olympian-style deities, similar to pop-culture imaginings of Greek gods and goddesses, just with Roman names: Jupiter instead of Zeus, Mercury instead of Hermes, Apollo — well, he’s the same in both languages — you get the idea.

This isn’t the place to nitpick at those associations: where they hold, and where they are strained or invalid. My emphasis here is that a lot of Roman religion, particularly in the older periods of Latin history, and the rites observed at the household level, operated in a sphere separate from these state-sponsored cults. Private religion focused on the health and prosperity of households and their members.

All Roman religion was based on a principle of exchange: quid pro quo meant “this for that.” Ideally, a good flow of communication and gifts established mutual trust (fides) between mortal and divine beings. These principles held true for relations with all the gods, but the closer to one's daily existence a deity or spirit came, the greater attention one needed to pay to those divine forces. (Source.) The point is that so-called “minor” deities were extremely important for Romans, in ways that are not obvious to those who awareness of Roman religion focuses on Jupiter, Juno, Minerva et al.

Those who treated their Lares well could expect to thrive.

The job of the Lares familiaris was to protect the family and provide a benevolent influence at moments of a change in age and status. Sometimes, they were considered the benevolent spirits of dead ancestors, which makes sense since in the earliest eras the dead were usually buried somewhere on the homestead. They protected all members of the household, whether free or enslaved, but there was a catch: they would not travel with the family if they moved. Thus, they can also be considered a form of genius loci. (A Roman returning home from a journey might say they were traveling ad Larem — to the Lar.)

All Lares were worshiped at shrines called lararia. Domestic shrines to Lares familiaris — family Lares) were placed in the atrium (main room) or peristylium (a small open court) of each house. They were almost always depicted as a pair of adolescent boys holding drinking horns in one hand and an offering plate in the other. The male figure at the center is the genius (personal daemon or tutelary spirit) of the head of the household. The snake is associated with a benevolent spirit called Agathodaimon5 who was also worshipped at home altars.

Above: a household lararium shrine.

There were actually many kinds of Lares: Lares Domestici (guardians of the house), Lares Patrii (guardians of the fathers) and Lares Privati (personal guardians) were part of the household ensemble. Other guardians were the Lares Permarini (guardians of the sea), Lares Rurales (guardians of the land), Lares Compitales (guardians of crossroads), Lares Viales (guardians of travelers) and Lares Praestitis (guardians of the state).6

One of the derivations of the name Larentia is from the Etruscan Lar, similar to Lara and Larunda (which is the Etruscan version of Lara), the nymph who was silenced and became the mother of the Lares. And one of Acca Larentia’s alternate names is Mater Larum: “mother of the Lares.”

Another etymological connection: “place of the laurel tree”

Laurus nobilis, botanical illustration.

The name Larentia is also connected with the bay laurel tree.

Strabo relates how this tree, and a place that was named Laurentum after it, were connected with the myth of the Trojan origins of Rome’s founders.

They say that Æneas, with his father Anchises and his child Ascanius, arrived at Laurentum, near to Ostia and the bank of the Tiber, where he built a city about 24 stadia above the sea.

Laurentum, is a name that either relates to the presence of many groves of Laurus nobilis, the bay tree, in the Silvia Laurentina, or — according to Virgil in the Aeneid — to a single, sacred laurel tree. The popular Roman names Laurentus, Laurentia (etc.) were used by families who wanted to be known for belonging to the first Latin capital city of Laurentum or as wearers of laurel wreaths awarded for triumphs or accomplishments.

Laurel has many uses in healing (Pliny listed 69 uses for it in his Natural History), so its presence was auspicious for practical reasons, but it also had a wealth of spiritual associations because of its psychedelic effects. “Mantic laurel” has been connected (at least) since ancient Greek times with inspiration and prophecy. The Pythia at Delphi is associated with laurel,7 and some believe that the earliest sibyls were mainly under the influence of laurel leaves. The Pythia is described by some late sources as chewing laurel leaves and shaking the branches in order to breathe in their essence. Poets seeking inspiration continued to ruffle the leaves and inhale their intoxicating fragrance well into the Christian era. Petrarch, for instance, punned on the tree’s name, feminized as laura, as l’aura, the “very breath of poetic inspiration.”

The Oracle of Delphi Entranced, by Heinrich Leutemann (1824-1905). Wikimedia

Acca Larentia’s most famous role

Everyone knows the legend, at least in its rough outlines: royal twins Romulus and Remus were born to a princess of the city of Alba Longa and abandoned because a usurper — the princess’ uncle — feared that his deposed brother’s sons could one day rise up and challenge him.

In order to prevent this from happening, princess Rhea Silvia, the daughter of deposed king Numitor, was made by her uncle to serve as a celibate priestess of Vesta. However, she became pregnant. She and her sons were all in mortal peril from Amulius’ fear, wrath, greed, and envy, so the desperate young woman had to do something with her newborn twin sons. Either she or someone else put them into the Tiber Riber.

The question naturally arises of who had fathered the boys. Many traditional sources (e.g. Strabo) say it was Mars who raped princess Rhea Silvia. The more skeptical Livy says she only alleged that Mars was the father for expedience. Others propose that it was her uncle Amulius disguised in armor who raped her. Alternately, Debra May Macleod makes Rhea Silvia’s brother Egestus (disguised as Mars) into the father of the two “pure-blooded” successors in her novel Rhea Silvia.

Mars and Rhea Silvia, Peter Paul Rubens, ca 1617-1620. Wikimedia.

If Amulius simply killed Rhea Silvia and her sons he might risk the wrath of Mars, so he decided to imprison his niece instead of having her buried alive. The children were to be killed either by exposure or being thrown into the Tiber River. As such stories go, he delegated the job to a servant who took pity on the innocent newborns. Thus instead of simply submerging them, he put them into a basket and the Tiber River — which of course was a deity in its own right — carried them to safety.

The basket eventually washed up and stuck in the roots of a fig tree8 at the base of the Palatine Hill. Romulus and Remus were then discovered by a she-wolf, who suckled the two boys and — in some versions — kept them safe in the Lupercal Cave.9

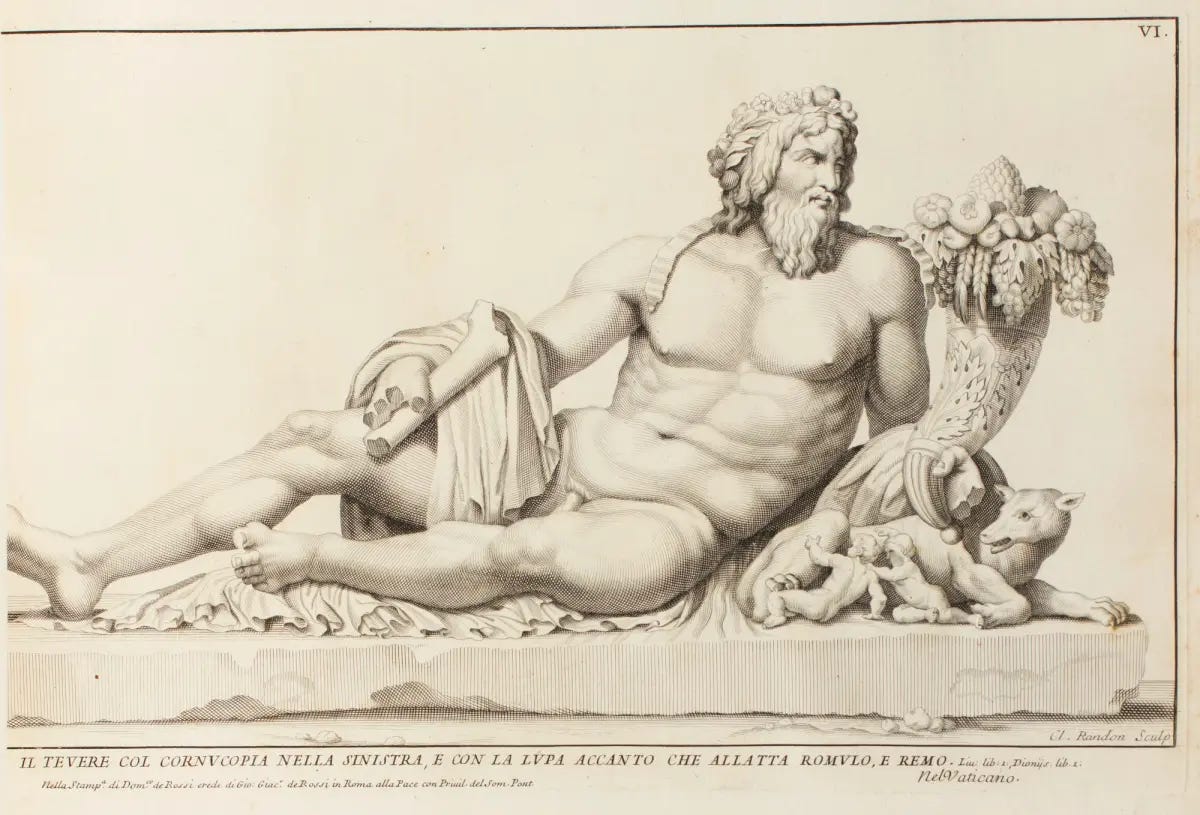

Tiber River with Romulus and Remus, Claude Randon, 1704. In the collection of the Royal Academy. Rivers were personified as gods in classical antiquity.

The twins’ foster parents

The mother wolf nursed Romulus and Remus with her milk and watched over them until they were discovered by a herdsman named Faustulus.

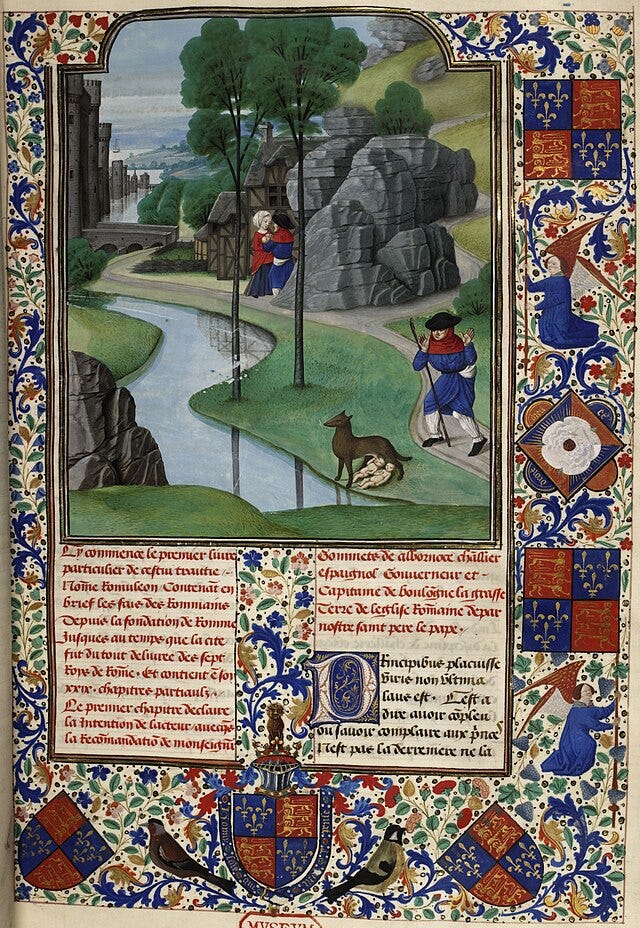

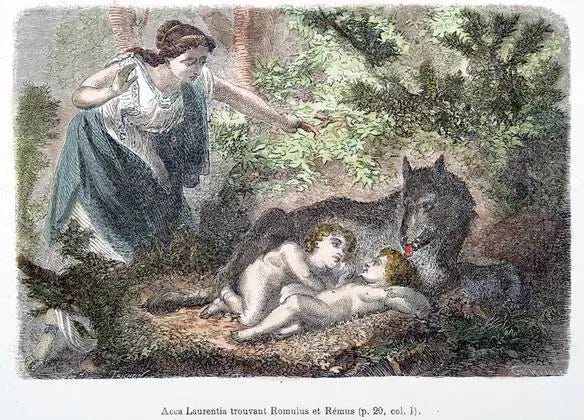

Two consecutive events are depicted in the painting above: Romulus and Remus are being suckled by a she-wolf on the bank of the Tiber, where they are discovered by Faustulus. Above, we see Faustulus giving the baby boys to Laurentia. Detail of a miniature by the Master of the White Inscriptions, 1480. Wikimedia.

Above: The Finding of Romulus and Remus, by Georgione (Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco, ca 1520. Städel Museum, Germany.

Usually, the story goes that Faustulus took the babies home to his wife, Acca Larentia, who became their foster mother and took over as their wet-nurse. The couple raised the boys in a modest, yet wholesome environment. (Faustus, in Latin = favorable.)

Let’s recap a little before we continue: Despite their inauspicious conception and abandonment, Romulus and Remus benefited from a perfect conspiracy of natural and supernatural powers. They had divine “biology” and protection (Mars as the “bio” father, Tiber as the temporary guardian), human “biology” and protection (Rhea Silvia as “bio” mother, Acca Larentia as foster mother), local geography (river, cave), and plant and animal milk (from the wolf and the fig).

Why did Romulus and Remus eventually die, despite being demigods? I think it’s because their nature mingled all three types: human, animal, and divine, and the average of the three — the human — is mortal.

Romulus and Remus, Charles de La Fosse, 1700. In this image, Faustulus and Acca Larentia are co-discoverers of the babies. This one, in particular, reminds me of Nativity scenes.

In the image below, Acca Larentia is making the discovery herself:

In some versions of the story, Acca Larentia and Faustulus were childless, but in others10 they had twelve sons. Sometimes, it is told that one of them died and Romulus took his place. In any case, all twelve brothers were raised to be pious and they made annual sacrifices in the fields (arvae) to bring fertility to the crops.

This is the founding myth for the Fratres Arvales, a priestly brotherhood who numbered an even dozen. The brotherhood was said to be established by Romulus in honor of Acca Larentia. Not much is known to modern scholars about their roles, but we know that they were “persons of distinction” (high social class) and their main duty was offering sacrifices to the Lares who protected the state. They performed these offerings both at the Compitales and at the Larentalia (Acca Larentia’s own festival). In the course of these rites, the Mater Larum was also given a offerings of porridge in a consecrated earthenware pot and two sheep.

She-wolves

Rome’s famous Capitoline She-Wolf with Romulus and Remus. The wolf was long thought to be an Etruscan work from the 5th century BCE, but interpretations of its actual age vary. The twins have been attributed to the sculptor Antonio del Pollaiuolo (late 15th century CE). Wikimedia.

The lupa wet nurse was supposed to be an animal, but then a human — Acca Larentia — steps in. But was she fully human? Among her many other associations, Acca Larentia is also connected with a goddess called Lupa or Luperca, which is deified version of the she-wolf. They are also thus connected with the Lupercal cave, the Luperci priests, and the festival of Lupercalia in a spectacularly circular logic which was understood to be such even by the ancients.11

Sometimes, Luperca’s husband is a rustic god of wolves and shepherds called Lupercus who brought fertility to the flocks. (Faustulus could be a later echo of the figure, as many myths make him the king’s master of flocks.) While being a god both of wolves and sheep sounds like a contradiction, it worked because his affinity and rapport with the wolves meant that he was able to protect the sheep from them. (This is similar to the idea that in order to be a healer you have to understand how to harm.)

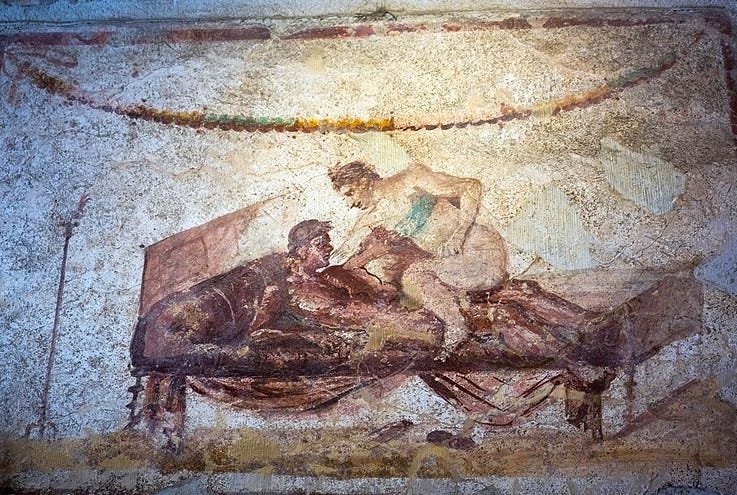

Another level to Acca Larentia’s association with wolves: in Latin, lupa (she-wolf) was slang for the lowest class of prostitute. This is the sense in which Livy uses it when he writes that the twins' wet nurse was a "she-wolf," though clearly the older tradition is that an actual wolf had nursed the babies.

Above: Erotic fresco from the Lupenar brothel in Pompeii, ca. 72-79 CE. Wikimedia.

A legend that takes lupa metaphorically rather than literally tells of a beautiful and civic-minded Roman woman named Acca Larentia who lived in during the reign of Ancus Martius (Rome’s mythical fourth king, ca 7th century BCE).

… a servant of the temple of Hercules, during days of celebration, invited the demigod Hercules to a game of dice, promising that if he [the servant] should lose the game, he would treat the demigod with a [feast] and a beautiful woman.

When the demigod had conquered the servant, the servant brought him Acca Laurentia, then the most beautiful and most notorious woman, together with a well stored table in the temple. After spending the night with Acca Larentia, Hercules advised her to try to gain the affection of the first wealthy man she should meet.

She succeeded in making Carutius, an Etruscan, (or Tarrutius in other versions), love and marry her. After his death she inherited his large property, which, when she herself died, she left to the Roman people. Ancus, in gratitude for this, allowed her to be buried in the Velabrum, and instituted an annual festival, the Larentalia, at which sacrifices were offered to the Lares [Ancient Roman guardian deities]. (Comp. Varr. Ling. Lat. v. p. 85, ed. Bip.)12

It is interesting that in the above version of the tale, the prostitute gains her wealth through her connections with a god and a man, but in others she earned it all through her own career as a lupa. In parallel, some legends say the benefactress Acca Larentia created an endowment for the city herself, while others claim she gave her foster son Romulus control of her wealth and it was he who became the economic patron of the city he founded.

“Roman Cameo of a Prostitute,'“ ca 200-300 CE, Aquincum (Budapest). The inscription reads: They say what they want. Let them talk, I do not care. Love me and it will do you good. Livius.org.

Plutarch says the Laurentia who nursed the twins was a distinct from the one who became a benefactor during Ancus’ reign, but other writers conflate them into one person. Clearly, as time passed, the name Acca Larentia remained in use, but there was a growing tendency to rationalize her as an ordinary mortal woman, and to transfer her sphere of influence away from family and chthonic cults (as the mother of the Lares) and recenter it in mythos of the city of Rome, where she was not only the mother of the twins, but an example of how the wealthy should donate their riches for the public good.

It is probably also significant that in these late stories Acca Larentia’s husband is an Etruscan. First, because of the etymological association with nobility or lordship:

Etymology: From older Lasēs, Probably from Etruscan 𐌋𐌀𐌓 [lar], 𐌋𐌀𐌓𐌔 [lars], or 𐌋𐌀𐌓𐌈 [larθ, “lord”], though it could possibly be from Proto-Indo-European *las- (“eager”), cognate with lascivus. Wiktionary: Lares.

And second, oh my! Lupus in fabula! This means “the wolf in the story" in Latin.13

The wolf motif is reappearing in another loop:

In the ancient association between the Etruscan word for death, and the Latin name for wolves. The pre-Indo European Etruscan language became extinct sometime between the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE. Among the words known to modern researchers are “vagina” (sheath), “death” — 𐌋𐌖𐌐 (lup), and “dead” — lupu (𐌋𐌖𐌐𐌖). And this loops us right back to the Lares, spirits of the dead.

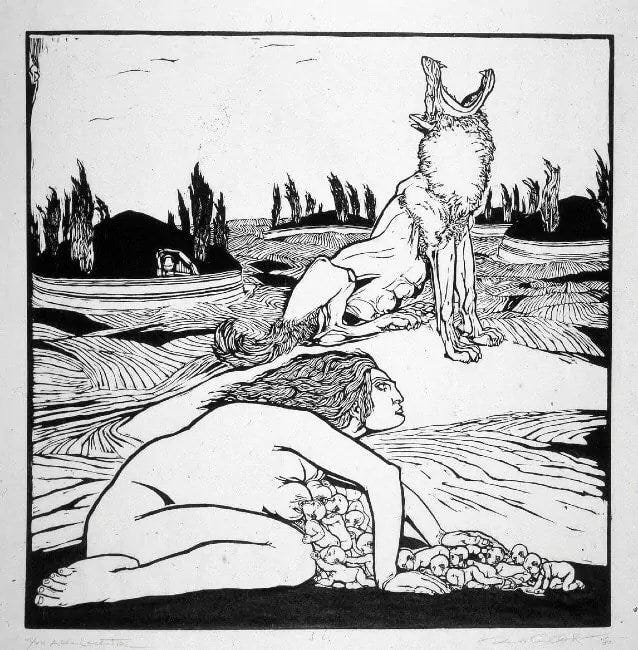

Acca Larentia, by Duilio Cambellotti, 1939. It’s a strange image. Why does the woman have an obscene number of babies striving to reach her breasts, while the disconsolate she-wolf is howling with swollen teats and no babies. The tumulus in the background is another interesting detail that suggests a chthonic ancestral influence, and an Etruscan influence in particular. The Etruscans built these mounds, and even entire necropoli with many of the structures clustered together.

Looping, twinning, doubling

Doubling and tripling of motifs in myths serves to incorporate several stories into one in a way that those who heard older versions can accept, and it multiplies the powers and legitimacy bundled into a figure or theme. These elements create a powerful sense of Déjà vu, which underlies the truth claims behind the myths.

Wolves and sheep; sheep and wolves; whores and kings; kings and shepherds; caves that are tombs and wombs and occupied by wolves and sacrificing priests; cities and the fecundating power of the wild … the themes become so interwoven that there is no real beginning or end to them — just tangled many loops.

Look at how many doubles we have: Romulus and Remus, who had two human mothers, each of whom has double aspects as matron/virgin and harlot. The twin Lares who were mothered by either Lara or Acca Larentia, who perhaps were and perhaps were not identical. The milk of the she-wolf doubled by the milky sap of the fig tree, which Romans assumed gave its name not only to Romulus but also to their city, whose voluptuous hills resemble the swollen teats of the bitch, aimed up at the sky.

The jokes, if they can be considered as such, about prostitutes and city founders not only have a long history, and are still used today. The word troia in Italian may refer to a sow (female pig) or it can also be a derogatory term for a sex worker. However, when capitalized it becomes the illustrious city of Troy, Rome’s fabled urban ancestor. Thus, and probably not coincidentally, Rhea Silvia has an alternate name of Ilia — the “Trojan girl,” as homage to her ancestor Aeneas. It is little wonder Acca Larentia ended up characterized as a whore.

Festivals in the darkest days

The merry and sometimes raucous Saturnalia (December 17-23) took place with an undercurrent of rites honoring deities or spirits associated with darkness and silence. (Much like some people today seek to connect with the stillness of silent nights instead of jingling all the way, all the time.)

Whether the mortal version of Acca Larentia earned or married her money, or passed her wealth to Romulus, who used it to make the city prosper, myths tell that the people of Rome were so grateful to her that they instituted a festival named after her.

The Roman festival of Larentalia was celebrated in honor of Acca Larentia every year on December 23. This was the last day of the week of Saturnalia (December 17—23). The day was also called Sigillaria after the custom of giving little figurines as gifts. Acca Larentia was among the figures gifted between friends, relatives and other extroverted merrymakers.

However, Acca Larentia also shared this day with the spirits of the dead. On the Larentalia, the flamen Quirinalis (the high priest of Quirinus, who was — to greatly simplify the matter — a deified form of Romulus) sacrificed to the Manes at a place where the alleged tomb of Acca Larentia was located.

One of the other goddesses honored around this bright and merry time was Angerona,14 who was associated with suffering, silence, and secrets. She had a somewhat ambivalent nature, since she both relieved people’s anguish and sorrows and agony, but also made them suffer if she felt it was necessary. She additionally.protected the city of Rome by keeping its true, sacred name silent and secret from its enemies. (It’s possible that, as some have claimed, Angerona actually was this name, but then that wouldn’t be much of a secret!)

Statue of Angerona by Johann Wilhelm Beyer. She is located along with 31 other statues depicting classical figures in the Schönbrunn Garden in Vienna (1773 — 1780).

Sacrifices were made to Angerona on her festival day of December 21, called — of course — Angeronalia. Interestingly, her offerings were given at the temple of another deity: Volupta, the daughter of Cupid and Psyche and the protector of sensual pleasure and forbidden loves. Volupta, too, often had a finger on her lips commanding silence and discretion about secret love affairs. This is, of course, is exactly what Lara had failed to do!

It is not known today exactly when the festival for the Lares Compitales (neighborhood/crossroads Lares who were the twin sons of Lara/Dea Tacita) took place. Some sources suggest it happened in December just after the Saturnalia and Larentalia ended, and others say that it was on one of the first days of January and/or that the date was not firmly fixed. But, in any case, it was in the depths of winter.

As I mentioned above, Dea Tacita’s festival was moved from its original date of December 23 to the Feralia on February 21. However, it is arguable that an echo remained in the observances for Angerona and Volupta.

The Festival of Lupercalia

This is perhaps the Roman festival that more people today have heard of than any other. First, I want to dispense with the modern notion that Lupercalia, which was held annually on the 15th of February, was some kind of precursor to our modern Valentine’s Day. It was nothing of the kind … (read Myth & Mystery's article on the subject if you have any doubts). It was a raucous festival that involved sacrifices of dogs and goats, semi-nudity, and fertility rites based on whipping women.

Lupercalia, by Andrea Camassei, 1635. Wikimedia.

Second, while it might seem that Lupercalia is derived from the word lupus (wolf), it’s not quite that simple. Rather, the festival was held in honour of the god Lupercus. His temple was located at the site of the cave – the Lupercal — where Romulus and Remus were suckled by Lupa, the she-wolf. It is there that the Luperci (the priests serving the god Lupercus, who was actually Faunus) would assemble and perform secret rites. So the simple biology of the wolf was transformed in a cultural complex.

Some of what we know is that two boys, sons of aristocratic families, were brought into the cave. The priests, who were also from the highest echelons of Roman society, nicked the boys’ heads with their knives, drawing blood. They would then dip wool in milk and rub it on the boys’ heads — but, strangest of all — the boys were required to feign laughter with the blood and milk dripping down their heads.

The Luperci also sacrificed two goats and a dog, and cut the some of the goat skin into strips. From these, they braided whips, which were dipped into milk to represent the wolf’s milk. They slathered themselves in oil, and then used what was left from the goatskins were used cover parts of their bodies in imitation of the half-wild Lupercus, who was represented as half naked and half covered with strips of goatskin. Then, the Luperci would run through the streets of Rome, touching or striking any person they met with their whips — especially women who wanted to conceive.

The rite served not only to promote fertility in individuals, but also, perhaps as a lustral (purification) rite for the Palatine hill, the area the Luperci ran around.15 This would be on-brand for the month of February, which was the last month in the archaic Roman calendar and generally a time of purification and connection with wild and chthonic spirits and with the dead. And who says that has to be done in a boring way?

The last Lupercalia was celebrated at the end of the 5th century: tradition says it was canceled by party pooper Pope Gelasius, who didn’t appreciate that the nominally Christian population was still partying in the streets in such an uninhibited manner. Others claim that it continued a bit later than that. However, despite that it was eventually shut down, the Lupercalia’s legacy remains with us in the word February, taken from februa — the purificatory goatskin whips used by the Luperci.

A goddess for all seasons

Acca Larentia’s myths encompass many areas of life. She has aspects of her myths where she is a working woman, a foster mother, and an engaged citizen. She is also an underworld goddess who keeps company with the beloved dead, and whose sons (the Lares) bless and benefit families. In her winter aspect, she symbolized the Earth’s dark, silent season when seeds are guarded till they can sprout, when animals await their season of rut, and when secrets are kept so that peace is kept among people. Goddesses associated with her were connected to the fecundity of wild places, and the abundance of crops. She was even part of the joyous and licentious festival of Floralia at the end of April, when sex workers were especially honored.16

Honoring Acca Larentia and Lara today

Despite her earthy, chthonic nature, Acca Larentia’s mothering — in the story of Romulus and Remus — is not a biological act, but one of kindliness and hospitality. Not everyone can or wants to become a mother (or a father), but anyone can take care of someone who needs nurture and guidance.

I always address Acca Larentia in my morning rites, and I believe she guides my mind and hands as I write. In my experience, she has been a kind of “muse” who inspires creative work that explores topics related to her myths. While she is neither very well known today nor was she known at any time as an artists’ or writers’ muse, she stands behind the building of what was once the most powerful city in the world, and her legends are still pulsing with life and vitality.

In terms of timing a special rite dedicated just to her, I see two obvious options: December 21 and 23. Over the last decade or so there has been a renewed interest in the ancient tradition of Mother’s Night. Most (neo)Pagans who celebrate it hold a ceremony on the night of the winter solstice. However, since my family has a Yule celebration on the night of the solstice I don’t try to cram too much into that one evening.

December 23, the Larentalia, happens to be the day when my father was born and his mother, my beautiful grandmother Marge, was killed by her obstetrician’s gross malpractice.

A colorized portrait of my grandmother from the early 1940s.

(Poor Marge never got to see or hold her baby boy, or say goodbye to her other two children, and they were all raised by a stepmother.) So this is when I celebrate Mothers’ Night, in her memory. But, as it is the Larentalia, I also honor Acca Larentia. This is a time when I connect myself with all my female ancestors, the Mothers of the deep and mythic past who dreamed all of us into being. (If my daughters one day also have daughters, the line will extend into the future, but that’s a matter of their choices and fates.)

What I do in my solo rites on this evening is not much different than what you can read in many other blogs and articles about others doing: I light a candle, offer wine and cake, and speak to all of these women from my heart.

Usually, I make a simpler cake, taken from the Gather Victoria recipe, which also describes the traditions associated with observing Mother Night, but last year I made this one, which — with the bright yellow physalis fruits — illustrates the Sun circling around a deep, dark forest. Where is the vantage point? Inside, outside, underneath, overhead, baking, waiting - hungry, serving, eating ... drinking wine — we are moved and guided through all the positions and called to act with compassion and self-respect in each one.

For those who enjoy reading a poetic text instead of feeling that they have to come up with their own address to their ancestors, Danielle Dulsky offers this blessing:

May the longest night shroud you in an exquisite cloak woven from raven feathers, hope, wolf fur, and mistletoe, carefully stitched by a faithful, heathen crone who invites you to sit for a spell beside her solstice fire. May you find a midnight home there, steeped in clove-and-evergreen belonging, deep in the dark and holy womb where the yet-to-come is nested.

May she bid you bless the Yule log with your breath and a rosemary sprig, and may you bring her an offering of story in return, telling her of those quiet moments from the last year when joy found you and made you suddenly whole, when grief tenderized your rough and forgotten places, and when you woke with a mysterious childlike hope in your heart.

May she brew you a home-cooked remedy for your human aches from pine smoke, elder wisdom, and cinnamon, and may she sing you soft songs in a language some part of your ancient soul remembers. Together, may you dream each other into being one pagan prayer at a time, and may you make a memory so mighty it sets time and space to shake, setting the dream in motion with the primal pulse of new beginnings and infinite possibilities.

Above: Matronae in a Roman villa. Wikimedia.

I bought this plate from this Romanian Etsy shop that makes reproductions. While I do not know exactly who or what the figures represent, to me they are an image of the Matrones, of the link between my female ancestors, me, and my daughters and their potential descendants, and of the Fates.

Now, the violets are finally emerging around my village amidst the first tender green grass. I’ll honor Lara this year by creating a raw clay bowl and filling it with moss and violets.17 I’ll pour wine over the bowl, and leave her offering at a crossroad, asking her to look over my beloved dead and to spare me and my family from idle gossip and wicked tongues.

Mosaic depicting the She-Wolf with Romulus and Remus, from Aldborough, about 300-400 CE, Leeds City Museum. Wikimedia.

Wolves’ tails are pretty straight — this is one of the features used to distinguish between the canid cousins. If you see a shaggy “wolfish” dog that has a curled tail, it’s probably got Husky or another similar breed in its lineage.

The black spot at the base of their tails is created by the violet gland/supracaudal gland on the upper surface of the tail. It’s believed to be used for intra-species signalling, scent marking, and perhaps to mark the entrances of dens. The gland’s secretions are fluorescent in UV light.

I’m obliged to Eliza from the By My Solitary Hearth blog for the pun.

Lemures were a malevolent species of di Manes. These spirits were created when someone died prematurely (in youth or childhood), through disease, war, or assault, or if they had not been given due burial and funeral rites. The spirits of these unfortunate people were unable to enter the underworld where they belonged and they were wont to cause mischief and misfortune among the living. The festival of Lemuria was celebrated in the Julian calendar on May 9, 11, and 13. Temples were closed on these days, and no marriage ceremonies were performed.

Ovid says the origin of the rite was in a Remuria established by Romulus to appease Remus’ angry and malevolent spirit. In any case, the lemures (and another class of mischievous spirit, the larvae) were propitiated with chants and offerings of black beans.

The householder, perhaps with others, walks barefoot through the house at midnight. He washes his hands in spring water, takes his thumb between the fingers of his hand, to ward off any ghosts, then takes a mouthful of black beans and spits them out behind him or throws them behind himself, over his shoulder for the hungry lemures to gather, unseen. He chants "I send these; with these beans I redeem me and mine" (Haec ego mitto; his redimo meque meosque fabis) nine times; then the rest of the household clashes bronze pots while repeating, "Ghosts of my fathers and ancestors, be gone!" (Manes exite paterni!). The householder washes his hands in spring-water, three times. When he turns to see the results of the offering, or exorcism, no lemures are to be seen. Wikipedia.

During the Compitalia, sacrifices of honey cakes were given to the Lares Compitales by representatives of each household. At least according to Dionysus, those who assisted in these rites were slaves instead of free men, because “the Lares took pleasure in the service of slaves” ( !!!) However, the slaves were otherwise granted liberty to do what they liked at this time. Another explicitly underworldly connection with the Compitalia was that each household put a statue of Mania, an underworld goddess by the entrance to their homes. They also hung up wool dolls representing men and women, with the request that Mania and the Lares would accept the figures instead of taking anyone from the household into the nether realms.

I’ve written a bit about Agathodaimon in this article, toward the end.

For more, see the Pagan Calendar blog's article on the Lares Compitales.

One of the main theories, which is that she was mainly under the influence of ethylene gases emerging from a crevasse in the temple, has spotty evidence. Was it instead methane, or CO2 and H2S? An alternative theory is that she was intoxicated by oleander fumes. In any case, querents approached the temple waving laurel branches.

Learn more about Roman (especially imperial) laurel lore here. The words “learn,” “lore”, “last” (in the sense of “to endure”), and “delirious” are etymologically connected via the PIE root *lois- which referred to a furrow in the earth, but I do not think that “laurel/laurus” directly associate with them, despite how well such an association would chime.

The Ficus Ruminalis deserves its own footnote. This was a wild fig tree that had many dimensions of symbolic and mythological significance in ancient Roman culture. The one in this story stood near the Lupercal cave underneath the Palatine Hill. This tree was sacred to Rumina, a deity who protected breastfeeding in humans and animals. (Not surprisingly, libations of milk, rather than wine, were offered to her.)

Romans distinguished between wild fig trees, which were considered to be male, and cultivated fig trees, which were female. Either type of fig (fruit) is somewhat breast-shaped when it’s closed (and looks like a vulva when it’s cut open). Rumina and Ruminalis ("of Rumina") were connected by some Romans to rumis or ruma, "teat, breast," but some modern linguists think it is more likely related to the names Roma and Romulus, which may be based on rumon, perhaps a word for "river" or an archaic name for the Tiber River.

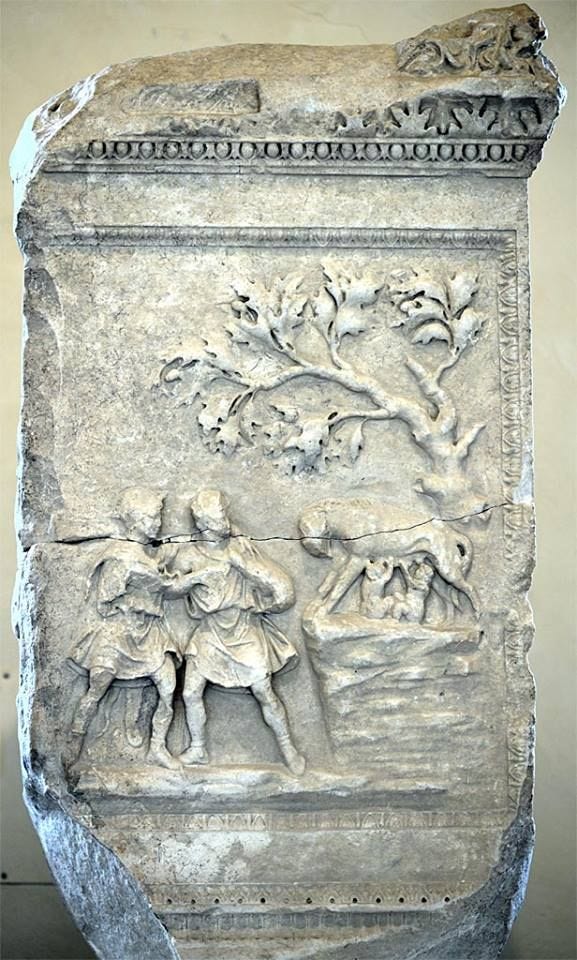

This marble altar which depicts the she-wolf nursing Romulus and Remus dates to the Augustan period. It was found in 1933 in Piazzetta di Porta Crucifera. Note the astonished figures of Mars and Faustulus.

A statue of the she-wolf was supposed to have stood next to the Ficus Ruminalis with the babies sucking at her teats. Some believe it was this sculpture group that is represented in old Roman coins. See Wikipedia.

Bronze Follis coin depicting Romulus and Remus and the she-wolf. Issued under the reign of Emperor Constantine between 332 and 346 CE.

For more about the mythic founding family of Rome, see my short article linked below:

Landscape with Ascanius Shooting the Stag of Sylvia

Claude Lorrain (1604/5–1682) was a French painter who spent the best — and last — years of his career in Rome. The master’s last canvas, Landscape with Ascanius Shooting the Stag of Sylvia, was made for his most important patron, Prince Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna.

Massurius Sabinus in Gellius.

Varro put it like this: “The Luperci [are so-called] because at the Lupercalia they sacrifice at the Luperca … The Lupercalia are so-called because [that is when] the Luperci sacrifice at the Lupercal.” Source.

Pretty loopy, right?

Figuratively it’s more like “Speak of the devil — and the devil appears.” In my article “Speak of the Devil! Lupus in Fabula!” I discuss the taboos around speaking the words for wolves, bears, and devils at length.

Angerona is sometimes assimilated to Feronia, a tutelary goddess of freedman, and divinity of nature’s wild forces which brings us back full circle to wildness (“feral” from the Latin ferus) and self-sovereignty. She also renewed wild places: Servius writes that when a fire destroyed her wood and the locals were about moving the statues to another location, the burnt wood suddenly turned green.

See “Mars the Lustral God” by Vincent J. Rosivach.

See Thalia Took.

Lara’s symbols are clay, soil and violets. Violets had a rich variety of resonances in Roman culture:

Violets also had a spiritual significance in Roman culture, as it was believed that the scent of violets was the sweat of the gods. For this reason, violets were thought to possess magical powers, and were often used as a charm or amulet to ward off bad luck. This spiritual power was further enhanced by their use in religious ceremonies, as they were believed to bring the protection of the gods.

Finally, violets were also highly important symbols of modesty, humility, and chastity in Roman culture. This is why they were often associated with young maidens, as it was believed that wearing a crown of violets would help to protect their virtue. Violets were also seen as a symbol of mourning, as they were thought to bring solace to those who were grieving.iolets were seen as an important symbol of peace and security in ancient Rome, as they were believed to protect the city and its citizens. This is why they were often planted around the city walls, as it was thought that they would provide supernatural protection. They were also seen as a symbol of hope, as they were believed to bring life-giving water to dry land. This symbolic power was further enhanced by their strong scent, which was believed to have the power to drive away evil spirits. In addition, violets were an important symbol of fidelity and trust, as it was believed that when violets were given as a gift, the person receiving them could not betray his or her word.

Violets also had a spiritual significance in Roman culture, as it was believed that the scent of violets was the sweat of the gods. For this reason, violets were thought to possess magical powers, and were often used as a charm or amulet to ward off bad luck. This spiritual power was further enhanced by their use in religious ceremonies, as they were believed to bring the protection of the gods.

Finally, violets were also highly important symbols of modesty, humility, and chastity in Roman culture. This is why they were often associated with young maidens, as it was believed that wearing a crown of violets would help to protect their virtue. Violets were also seen as a symbol of mourning, as they were thought to bring solace to those who were grieving.

Thank you for the share, Alice!