In a sense, this story opened up the gateway to my recent turn toward writing, which began in February 2021. What immediately preceded it was an experience where I understood more deeply than ever before that everything we perceive, know, and understand is story, and I wanted to be a more active participant in this endless give and take — so I sat down to write. Acca Larentia opened this gateway to inspiration and I still catch glimpses of her behind all my other writing, whether fiction or nonfiction.

Lupercalia

February 15, 2020

Jeremy pushes at the heavy pelt spread across the quilt covering his chest and belly, trying to get it off him. It’s hard to breathe. Two eyes the color of burnished bronze open, fixing on him, while the shaggy-coated bitch considers whether she still needs to keep her charge warm or should let him sit up. Lying on his back on the rickety guest cot, the man lifts his head and opens his shoulders wide, imagining wings pressing against the mattress, trying to force a full breath in. Cassia leans forward to lick his chin, then shifts down to lie on his legs, allowing him to stretch his upper body but not to rise. Jeremy’s lungs feel like cracking leather and a skirling whistle spirals through bronchial tubes, like a red kite circling over parched hills seeking its prey.

I’m suffocating. This thought drives a spurt of adrenaline into Jeremy’s blood, and the last wisps of dreams evaporate around him as he puts his elbows, then hands behind him and painfully elevates his torso. He’s no longer in a cave among shapeshifting shadows; no longer watching boys in rough tunics and fur cloaks tumble-play on a rocky hillside. Becoming more aware of the room that encloses him, he notes the wan light coming in through the plate glass window, which meant he had spent another night in Helena’s cabin. The pressure in his bladder indicates it’s time to get up.

“Get off me, wolf!” he gasps.

Cassia mutters from deep down in her chest, as if disagreeing. She sniffs his breath: he’s still full of the sickness, she determines. The man’s place was in the bed, and her duty was to keep him safe. That meant keeping him warm while he shivered, weighing him down when he thrashed in his sleep, and updating Helena on any developments.

“Cassia, pleea—” his voice cracks.

Helena enters the room wearing grey sweats and a china blue terry bathrobe with innumerable picks pulled out of it, probably the work of the many tiny fangs and claws of puppies she’d held close over the years. She wears open-toed slippers and has her straight brown hair pulled back into a messy knot in the back. Her eyes are puffy: either she has just woken up or she slept badly.

“Dolu, Cassi – nech ho jít na záchod!” she commands, then translates for Jeremy: “I told her to let you up so you can go pee.”

Cassia looks first at Helena, then at Jeremy. She slowly puts her front paws on the plank floor, stretching to her full length with her tail reaching for the wooden ceiling, then she jumps down and moves her body through what any yogi would call a series of asanas. The wolfdog lunges at the door’s old brass handle and lets herself out into the garden. Helena closes the door after her.

Jeremy rubs his eyes with the sleeve of her sweatshirt that he had slept in, because his supply of clean clothes had already run out. Then he begins coughing, his lungs heaving against the dry crud that was stuck in them and wouldn’t come up. Gods, what day is it? His phone displays the date: February 15. His fourth day in the cabin.

Jeremy’s legs feel like waterlogged beams from three days and three nights mostly lying in the cot while his fevers waxed and waned. He stands up, dizzy and weaker than the day before. Helena comes to his side, and without saying anything, she holds his elbow to keep him steady as he stumbles toward the WC. When he emerges, hands still wet and smelling of soap, she seats him at the small table in the center of the cabin’s main room. Inwardly, he is mortified at being so helpless and dependent. He faces the wood stove, which has a cheery blaze thrusting behind the sooty glass and a saucepan bubbling, probably decocting his dreaded morning tea, on top. His head reels, and he wants to talk with his hostess, but about anything other than his illness.

“Good morning! I forgot how to say that in Czech. Oh, and I want to wish all of you a happy … what do you call it? It’s when someone has a personal holiday, like when they have the name of a saint.”

“Dobré ráno,” Helena answers, her taut cheeks drawing into a surprisingly mirthful smile. Most of time, only animals managed to break her solemn expression. “You mean a svátek, right? It’s called a ‘name day’ in English. Hmm, the calendar says it’s February 15. All the women called Jiřína are celebrating. Is this a day for Jeremies too? I don’t think we have them in our calendar.” Her lake-blue eyes twinkle over the soggy bags hanging under them.

Celebrating his own name day hadn’t occurred to him. He begins shaking his head but is forced to close his eyes against the vertigo. Today was the day when the Romans celebrated Lupercalia, a day named after wolves, with rites dedicated to purification and the renewal of life force. And here he was, surrounded by wolfdogs.

“No, no. We don’t celebrate this kind of thing in Canada. But the Romans – back in ancient times – had a holiday for them.” He turns his gaze away from the desiccated wooden tabletop to survey the room. Cassia is still outside, but there are several other wolfdogs lying in the floor or lounging on pieces of furniture, and he waves his hand inclusively: “They called it Lupercalia.”

Lupercalia, by Andrea Camasei, ca. 1635. Wikimedia. For more on Lupercalia, see this article by Myth and Mystery.

Helena smiles. She knows about Lupercalia, but it had never occurred to her that she might celebrate it. Outside of work, most of her life was centered around wolfdogs: she shared her cabin and small garden with old mother Cassia, father Strider, and their daughter Flavia, who would hopefully bear her first litter this summer. But this small nuclear family is only part of the pack staying with her now. Two more wolfdogs are visiting while their owners are away skiing, and there were also Bart and Berenika, Cassia and Strider’s last two puppies. Their brothers and sisters had already been sent away to their new homes, and these two would go home to stay with their families next week. Altogether, there were seven wolfdogs on the premises. Sometimes Helena’s friends called the overcrowded cabin a “wolf spa,” with reference to the famous Bohemian resorts where clients could be immersed in beer, honey, chocolate, or perhaps some other favorite vice that becomes a health-bringing virtue in fulsome excess.

The two-room structure was never intended to be a year-round home. It should have served only as a place for hobby gardeners to rest and take their tea during the growing season. “Colonies” filled with cabins like this on tiny garden plots can be found all along the Berounka River. Once weekend refuges for people fleeing the dull grind of cities and communism, they eventually became permanent homes for a growing cohort of Prague’s middle-aged precariat – like Helena, a chiropterologist whose research on bats and other academic odd jobs don’t pay the bills. To fill in the gaps, she breeds Czechoslovakian Wolfdogs, a canny hybrid between German Shepherds and Carpathian wolves that look almost exactly like wolves and have their sharp senses and social instincts, but are more tractable and less afraid of humans.

“I think I need to lie down again,” Jeremy says. Helena pours kibble into two small bowls for the puppies, and then guides him back to the cot. She puts a hand on his brow, and then tucks him in under the quilt. Soon, Cassia returns and lays her soft grey muzzle on his shoulder. He breathes in the scent of her warm fur. Like a dog’s, but with a tingle of snow in it. Like a crackling fire, but in the forest rather than by the hearth. This was what he imagined, since his sense of smell had departed. He reaches a weary arm across her neck and she lets him scratch behind her ears and run his fingers into the thick ruff around her neck.

He reaches to the floor for the book his sister had given him for Christmas – a new edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses with commentary from an Oxford scholar. The night before, he told Helena the story about Minyas’ daughters who were punished for not joining the Bacchic festivals by being turned into bats. “As a measure of prevention,” she declared, they would honor Bacchus by drinking a cup of mulled wine together. And then another. Well, at least it took the edge off their awkwardness and the seesaw he was riding between tedium and delirium.

Helena was known for being aloof, and they had been near-strangers who had only communicated on online forums together before she took him in, but she seemed to be thawing a little. He didn’t know what her opinion was of him, but he was starting to think of her – and the pack – as friends. I have nothing else to offer her, he thought, but she seems to like stories. Maybe to ight we can celebrate Lupercalia with the legend of the she-wolf who raised Romulus and Remus.

Cassia heaves her body up onto the bed and stretches lengthwise next to him; her shaggy back pushing against his back as he shivered under the duvet. “The stories are for you too, Cassia,” he mumbles. He wonders for a moment which one – Helena or Cassia – was the foster mother in this household, and which one was the daughter. Chicken or egg; wolf or woman? Did humans domesticate wolves, or was it the other way around?

He opens the volume and flips back to the index seeking a reference for Lupercalia, but it wasn’t there – it must be in one of Ovid’s other works. The Book of Days, perhaps? He’d look it up later. Now, he is too fatigued to think about it. He puts the heavy hardback on the floor next to the cot and tries to breathe slowly and deeply with his eyes closed. Cassia’s breath has already slowed to the rhythm of deep sleep and he lets it guide him into a state that is neither asleep nor awake.

A sleeping Czechoslovakian wolfdog — Helli (my photo)

In a fugue, Jeremy’s mind pitches back to the strange forms he had observed in the Koněprusy Caves the day he fell ill: humans shifting into animals, and animals transforming into humans, just like in Ovid. A female figure emerged from behind a stalactite. She wore a deep blue mantle and had long curling hair. This lady … is she a goddess or a mortal woman? I think she … maybe … I shouldn’t have let them talk me out of studying classics! When he realized he was hallucinating he knew it was time to get out of the cave.

Jeremy had entered university with excellent Latin and the desire to study classics. But after his first semester his parents – and step-parents – insisted he choose a STEM field, because it would offer him a better livelihood. He chose biology, where the dead Roman language was still used by the living, and eventually began specializing in bats. He enjoyed field research outdoors at night and in caves; he had good mentors; and he engaged in environmental and conservation advocacy. A postdoctoral grant covered his trip to Czechia, where he had joined the international team conducting the annual bat census. On the last day of the survey, he felt faint in the early morning. About an hour after lunch, his legs were hardly keeping his upright. He headed back to the entrance of the cave and collapsed near its mouth. A researcher from Finland found him there and called for the Czechs to assist him. They decided that Helena would take him home, since she didn’t have any human household members he might infect. A week earlier, a Mexican colleague had also reported feeling ill, but he flew back to Mexico City. Perhaps Jeremy had caught something from him – who could say? It was winter, after all. Flu season.

The Winter Moon and her Wolves, by Pantavola.

The doctors Helena called refused to believe that the Chinese virus filling headlines had already reached Europe. “Your friend has influenza,” they said. “It’s especially bad this year. He probably got tired from traveling and spending time in the cold. Tell him to rest up, drink fluids, and stay out of medical clinics. There’s nothing we can do for him, and he’ll just trade germs with other people and end up sicker.” Jeremy canceled his flight home and told his housemates and parents he’d be staying with one of his Czech colleagues until he felt better.

“Drink up,” Helena says, holding out a heavy handmade mug with swells of steam pulsing out. Jeremy opens his eyes.

“Fuck you very much, I don’t think so!” he groans, knowing she didn’t mind rough language.

Inula helenium, elecampane. Hellish bane, he thought. He never took his medicine without a protest, even though he could feel that each cup lightened the congestion in his lungs. But its earthy, bitter taste made his stomach crunch into knots.

“Ah, the famous Canadian good manners!” she retorts, attempting not to chuckle.

The first time she had served elecampane to him she said: “Enjoy it while it’s hot; you’ll really hate the taste when it’s cold,” but now, each time, she simply remarks “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” with a wink. She doesn’t hover over him like an overprotective mother. It’s up to him to drink the medicine. Three times every day.

Elecampane, by Elizabeth Blackwell, 2014.

A fit of coughing wracks Jeremy’s upper body, causing Cassia to roll off the bed and shuffle over to the wood stove. Helena must have renewed the fire while Jeremy was dozing, because the room is palpably warmer and the stack of firewood is smaller. The old she-wolf leans as close to the fire as possible without singing her fur. She watches Helena walk over to the kitchenette at the side of the room, but one ear remains cocked as she listens to the man’s cough.

Cassia is replaced at Jeremy’s bedside by Strider, who stands over his hips and watches until the spasm abates, ready to summon Helena if needed. This old fellow was the only member of the pack who drooled: the tongues of all the others were as dry as well-wrung washcloths. The other adult wolfdog in the room, Flavia, is reclining on the army blanket covering Helena’s old couch with her legs delicately crossed, like the portrait of Empress Josephine sitting on velvet cushions. The puppies scratch at the door, whining.

Jeremy lifts the heavy earthenware mug that Helena had placed on the bedside table and gulps the decoction as quickly as he can without retching. Even without a sense of taste, the receptors in his throat tell him how bitter the drink is.

“Look at you getting stronger!” Helena declares approvingly, and she takes the empty mug out of his hands and sets it down on the windowsill next to the cot. The ghost of the healing tea exhales a leaf-shaped puff of condensation onto the glass. Jeremy watches as the ivory light of early morning dulls under a cloud, and he can see snowflakes falling on the frozen mud of the garden. It’s cold enough that they remain, and soon the bare dirt begins to look like sugar-sprinkled gingerbread.

Helena leans down to pick up the puppies Bart and Berenika, who have just started racing around the room, mid-scamper: “Here, have a puppy. Have two,” and she pushes them into Jeremy’s arms. The surprisingly well-muscled little beasts snuffle and sample his scruffy cheeks, his sweatshirt, and the beads around his wrist. Ow! Their teeth are sharp as flakes knapped off a spearhead.

“These things feed on human blood, right?” Wincing, he sets the squirming Berenika on the floor on one side of his cot and gives floppy Bart a nuzzle before putting him on the other. Helena laughs, and then goes into the other room; the room where she sleeps, works on her computer, and keeps the bats she rehabs away from the wolves. The puppies clash and tangle themselves up underneath the cot, then Berenika’s front half emerges and she yarfs a few chunks of wet junior kibbles on the floor.

Jeremy feels ashamed of his dependency. Helena even helped me walk over to the toilet. I’ll do at least one little thing for her – I’ll just go clean the mess off the floor so she can get a break for a few minutes. He slowly assembles himself into an upright position and uses the bedside table for leverage to heave himself up onto his feet. Strider stands by, his gaze steady as the old iron railing around the cottage’s well. All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well …. Jeremy intones, swaying a little as he makes his way toward the sink, where there are rags hanging on wooden pegs.

As he reaches for one that looks older than the rest, the door bursts open – one of the visiting wolfdogs had lunged at the door handle, opening it for himself and the other one. In a blast of frigid air and clicking claws the snow-spangled pair dash past the sick man, knocking him off balance in their rush to shoo Flavia off the couch. Jeremy tries to catch the door frame, but he doesn’t extend his arm far enough and barely keeps himself from falling. The cold immobilizes him; he is unable to take a step and reach toward the kitchen counter.

From her room, Helena hears the door and comes running to close it before the chill of the outside fills the cabin. Because while wolfdogs are able to open the door, they cannot close it. She sees her colleague hanging on the door frame, near to collapsing, and she rushes over to him and flings one of his limp arms over her shoulder. Flavia comes over to help escort him back to the cot, which is now occupied by the two visiting wolfdogs sitting at its head and foot like a pair of sphinxes. Helena shoos them away, then tucks Jeremy in under the down quilt, adding an unzipped sleeping bag on top. She picks his book up from the floor and puts it on the table, out of harm’s way. Flavia sniffs Jeremy’s face and goes back to her couch, again posing like a young empress. Her eyes are closed, but she is surveying the scene with her other senses: her ears and nose quiver and her eyebrows shift with her contemplations.

Refusing to be banished, the two visiting wolfdogs jump back on the cot and weigh Jeremy’s legs down while his brow breaks out in fresh sweat. His eyes have been closed since Helena caught him at the door frame, and he is sucked back into fugue dreams of caves, but this time he also sees wolves prowling among sheep. On a hillside, then in a cave. The wolves were not hunting, but herding the flock into the cavern mouth. Their feet and their faces were distinctly human … They were human, but outcasts: people despised them. He shifts into the story, practicing to tell it to Helena and the wolves later.

No one knew when the first wolf cults arose. Surely, they were older than the Romans, the Etruscans, and even the Greeks. Wolves were the first watchers of mankind. Tutors and healers, friends and accomplices. But also rivals and reviled foes. People dressed as wolves to lead war bands, but also to conduct raucous healing rites such as the Lupercalia. He realizes who the figure was that he had glimpsed in the Koněprusy caves and in his reverie: Acca Larentia.1

Before any roads led to Rome, the shepherd couple Acca Larentia and Faustulus built a cabin and filled it with the children of “wolves.” Acca Larentia was a former lupa herself; a woman who earned her bread on her back. After she bought her liberty and pledged herself to the freedman she loved she hoped they would have a child, but the gods withheld their favor. And yet, there were children to be had from the towns, babes birthed by the other “she-wolves” who refused to kill them as custom demanded. These unwanted children became the former lupa’s pups. No one knew how many she had, because – officially – all of these children were dead.

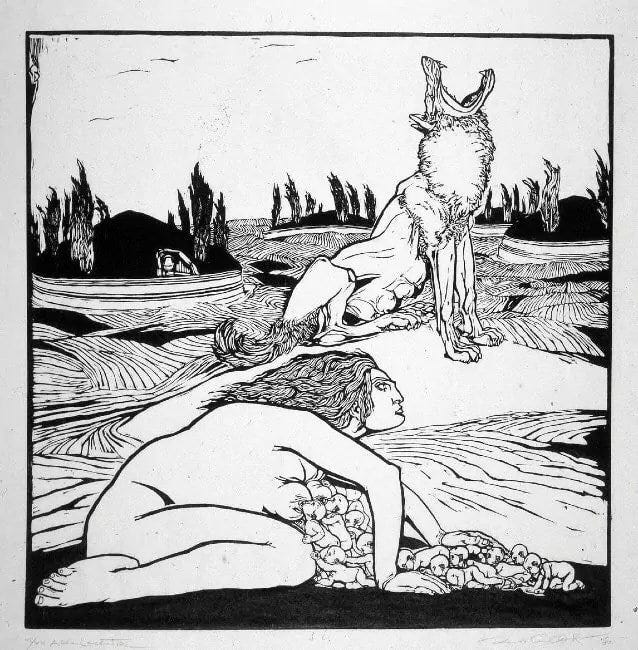

Acca Larentia, by Duilio Cambellotti, 1939.

The two foster-parents kept their children high and safe up in the hills. They dressed them in rough grey pelts, and soon their tender feet were as hardened as the paws of any other animals that roamed the woods and high pastures. Deep in the hollows inside the hills, witnessed only by the fluttering bats, Acca Larentia taught her boys and girls how to change their shapes. With the furs they tied on their backs and the moves they’d learned, they could produce convincing imitations of real wolves. Good enough to scare shepherds at a distance They stalked, lunged, and leapt, and also learned to play flock-beguiling tunes on bone flutes.

Father Faustulus trained the nimble, wolf-masked turnskins to rustle sheep. They would work on their feet instead of turning tricks on a hard stone couch down in the city, in the valley, amidst the noise and stench of humanity. Or serving in a household where the duties and expectations were often the same, and the pay even worse.

In the caves where phantasmic stalactites suggested transfigurations between one form and another, Acca Larentia also initiated her young wolves in rites she had learned from the subtle and strange women who lived in the woods beyond the high pastures, the half-feral aunties who had raised her before she was captured and sold into service in Alba Longa. These were women who could sing an arrow out of their bows into the heart of a hind; women whose tools could slice open the belly of a passing cloud to make it rain; women who changed out of one skin into another when it suited them. The animals and elements provisioned them; the weather humored their moods; they kept counsel with the dead. Men were afraid of these women, and everyone feared the young band of rustlers led by her eldest two, Romulus and Remus, whose wiles always kept them far away from justice, far from the demands that they bow, bend over, or starve.

Faustulus died at a venerable age in his bed in the couple’s cabin, and, with the cabin beginning to fall down from neglect, fierce and self-sovereign Acca Larentia retired to the Lupercal sanctum in the depths of the Palatine Hill where she practiced the art of passing back and forth through lupu, the veil of death. Some still scorned her as a lupa, but others say she became immortal. And there were many other legends besides these. Jeremy would tell Helena as many as he could remember or imagine. She’s a lot like these women with their wolves, bats, and potent herbs … and when I wake up, I’ll …

… he gasps out one last dry cough then falls into warm depths where dreams cannot penetrate, forms remain unresolved, and the healing chthonic exhalations of the ancient realms can reach up and envelop him. The snow lashes cold air behind the window like a lace curtain waving in a storm wind. Covered in thick grey furs, watched over by sharp amber eyes, and protected by the ancient friendship between wolfkind and strange humans, Jeremy groans in his sleep as the sweat pours through his skin and his muscles unclench.

Good wolf mother Cassia has been watching from her place near the stove since he was put back in bed. She listens to his breath even out, sniffs him and detects the resurgence in his vitality, and then goes to find Helena and bump her hand to impart the news that all will be well.

* * * * * * * * * * * ( the end ) * * * * * * * * * * *

Helena, the human wolf-mother in this story, is a real person. She is a chiropterologist (bat expert) and shares a tiny wooden cottage with a pack of Czechoslovakian wolfdogs, much as I have described. Her wolfdogs’ names have been changed, and Jeremy is an entirely fictional character.

As some of you know, I live in Central Bohemia (Czech Republic) and I also have two Czechoslovakian wolfdogs: Helli and Xaverine, or Xavi for short. Xavi is Helli’s daughter, and Helli is the sister of one of Helena’s wolfdogs.

Above: this is Helli, my older wolfdog, standing guard by our door in 2020.

Above: Wolfdogs are not allowed to sit in my armchair, but when I forget to put a barricade up they pop into it as soon as I’ve got my back turned. (Helli, December 2024).

Above: Xavi and my youngest daughter in 2016.

Helli and Xavi enjoying a view of the reservoir where we live. (This cliff is about a 20 minute walk from our home.)

Acca Larentia is an old Etruscan goddess who has many overlapping myths, which center around wolves, foster motherhood, self-sovereign women, and the earliest mythic origins of Rome. Sometimes, the myths portray her as a mortal woman, but the ancient patterns also come through these stories. I am writing a regular (nonfiction) blog post about her which I hope to release soon.

Thank you for this lovely story which brought to me the warmth of your cottage and the beauty of your wolfdogs! I would very much like to visit such a place at some point.