A Bull Story, a Deer Friend, and a Horse Tale

Making land and sovereignty claims using animal proxies

The town where I (mostly) grew up1 was originally inhabited by the Nissequogue people.2 Everyone grew up hearing the story of how the land was given as a gift to town founder Richard Smith by the Indigenous people in gratitude.

A 1939 mural by Robert Gaston depicting Richard Smith riding his bull, witnessed by colonizers and Native people.

Smith’s colorful legend is a lot nicer than the genocide, land grabs, deliberate spread of pestilence, and breaches of signed treaties that characterized most transfers of Indigenous-owned land to Europeans.3 And this is one of the reasons why it retained its appeal centuries after “Providence”4 and “manifest destiny” that favored white people’s property ambitions started leaving the bitter taste of blood and ashes in retellers’ mouths.

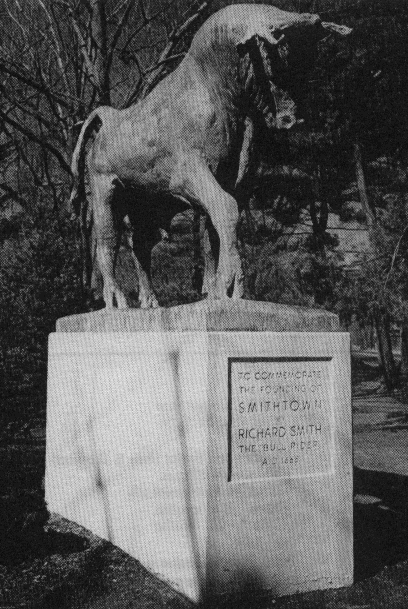

The tale went like this: Richard Smith was famous for having a tame bull named Whisper whom he like to lead around town and/or ride around on (hence his nickname “Bull Smith”).5 While riding on a bull sounds quite eccentric today, historians have pointed out that in the American colonies in the early 17th century, horses were rare and exceedingly expensive, and it would not have been so unusual to use cattle in their place, even as mounts. I grew up not only seeing the Smithtown Bull statue, but also looking at the lithograph below in my family’s home:

The Bridal Procession of John Alden and Priscilla, by Charles Yardley Turner, 1886. It depicts a wedding that took place in 1621 and was commemorated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his epic poem “The Courtship of Miles Standish.”

A copy of (The Bridal Procession) hung in my family’s dining room for many years, and — I’ll be honest — I never liked it, for the many visual suggestions that this “Pilgrim” couple with their funny hats, buckled shoes, and cattle were about to “settle” the “wild” land, assisted by the musket-toting men in their retinue. Why couldn’t they have made better friends with the Natives instead of parading around armed like that?

You could see that this uneasy idyll was only moment away from the crushing wave of European settlement that would try to remake the place they’d found in the image of England: land would be stripped of most wild growth, cattle would graze everywhere they could be fenced in, and church bells would ring out across the land, driving away spirits resistant to the hierarchy of Heaven over Earth.

So why — according to the town legend — would the Natives give anything to Smith? It was said that on the evening of her wedding, Heather Flower, the beautiful daughter of Grand Sachem Wyandanch, was captured by a band of Narragansett raiders, who carried her away to Connecticut. Richard Smith rescued Heather Flower and the sachem was so grateful that he offered the Englishman all the land he could ride around between sunup and sundown on Whisper’s back.

Above: Oh myyy! as George Takei would say.6 Does she know that Smith is married and the father of nine children?

The legend tells that Smith — who was already a large-scale landowner — chose to take his ride on the summer solstice to get the maximum hours and minutes of daylight. And, in order to increase the chances of Whisper hustling speedily along the 55-mile track, he led one of the bull’s favorite cows around the route the night before to mark it with her scent. Their legendary trek began in what is now the eastern end of Smithtown, leading south to Ronkonkoma, west to Hauppauge and north along a route now called Veterans Memorial Highway, then to Town Line Road, and finally ending up at the territory’s northern boundary at the edge of the Long Island Sound.

One version of the story includes the detail that at noon, the man and animal rested in a shady hollow. Smith had a snack of bread and cheese, which gave the road they were on the name Bread and Cheese Hollow Road.

This recently-installed monument indicates pretty clearly that we’re talking about a legend, and not verifiable facts. (wink, wink!)

We know that Smith was a very ambitious man, so why would he take a break instead of just eating his snack atop Whisper? After all, he had taken every other possible measure to ensure that his ride would be as long as possible.

Hawthorn tree in bloom in England, with discussions on how it can be used in food and drinks: wildfoodie.co.uk.

This theory makes more sense: Smith had grown up in Yorkshire, England, a land where hawthorn trees are plentiful and are used a) as boundary markets between territories, and b) the edible leaves of the tree are referred to as “bread and cheese.” Smith most likely had a hawthorn tree planted at this site in order to mark the partition. In the early colonial days, this was a common practice that was much more economical than using wood or stone fences.

While the hawthorn tree is speculation, and bull riding was a real practice, the rest of the story is certainly a myth. Even the later presence of one or more hawthorns wouldn’t prove anything: Smith could have planted the trees without having taken his famous ride.

However, if there is any “whisper” of truth to Heather Flower’s rescue from Narragansett kidnappers, Lion Gardiner,7 another English settler who was friends with Smith, was the hero. The Gardiner version of the rescue story says that after the bride had been recovered, the rescue party took her to Smith’s home in Setauket, where she was returned to her father, Wyandanch.8 The Grand Sachem pledged a gift of land to Gardiner in gratitude, but in 1663, Gardiner sold these Nissequogue lands to Smith.

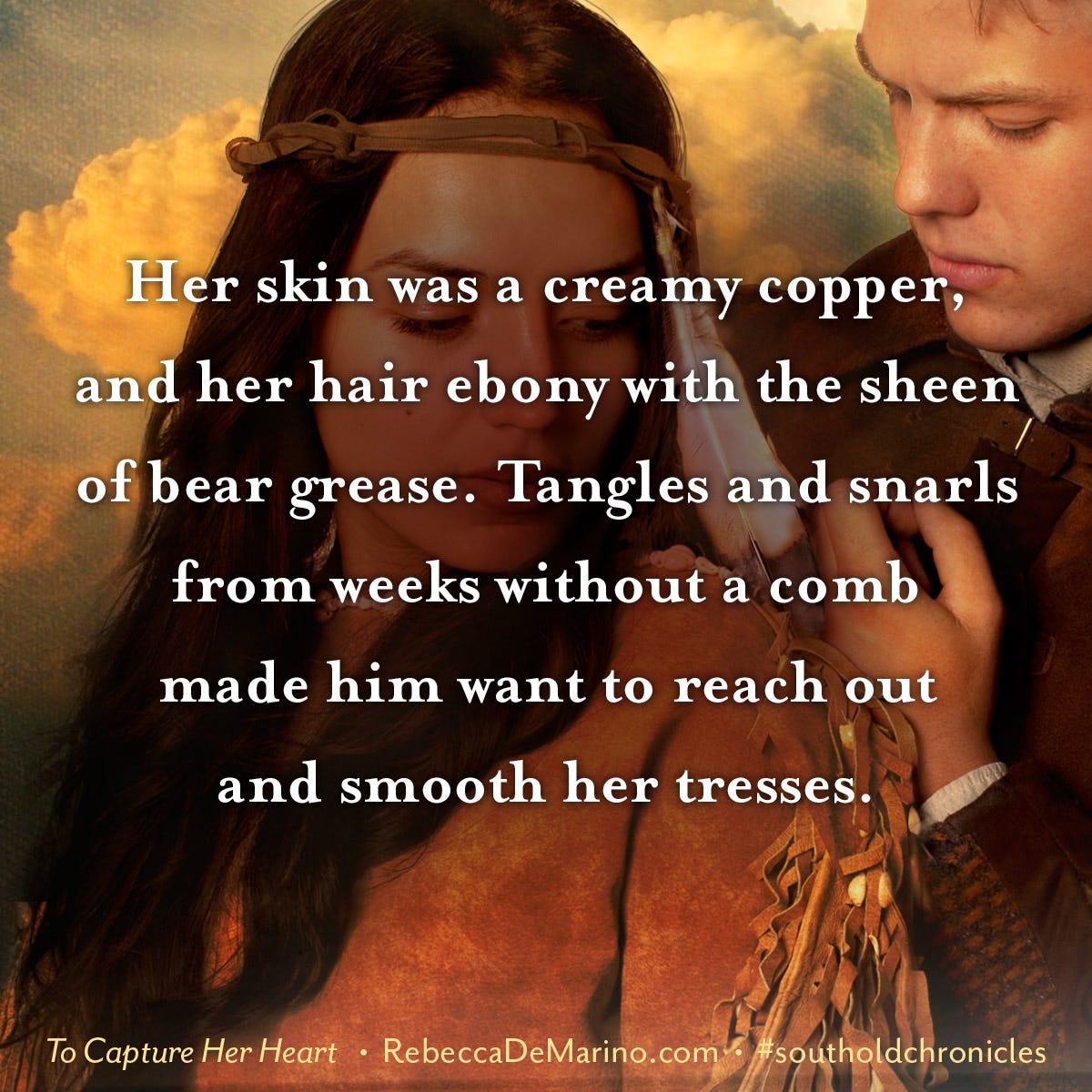

Yet, questions remain: was Heather Flower a historically attested person? It difficult to say with certainty. The novelist Rebecca DeMarino has outlined four possibilities:

She was Quashawam, the daughter of Grand Sachem Wyandanch, and Heather Flower was her nickname. Historically, records exist showing Quashawam became Grand Sachem of the Montauk when her parents and brother died.

She was Cantoneras, a Long Island native from Eaton's Neck who married the Dutchman Cornelius Van Texel or Tassle, whose granddaughter, Katrina, is of Washington Irving's Legend of Sleepy Hollow fame.

Wyandanch had two daughters, Quashawam and Heather Flower.

Heather Flower is a fabrication, as well as the story of the kidnapping of Wyandanch's daughter. Although Lion Gardiner's personal papers include an account of paying a ransom to the Narragansetts for the release of Wyandanch's daughter, the lack of a Montaukett written history clouds the matter. Some have alleged Gardiner may have written the story only to support the colonial's political motives.

Above: an artist’s interpretation of Heather Flower/Quashawam/Cantoneras.

Two years after Smith purchased the land, colonial governor Richard Nicolls acknowledged his ownership; thus, the town of Smithfield (later, and now called Smithtown) was considered to be formally established in 1665.

The bronze memorial statue to Richard Smith “The Bull Rider” and his bull, Whisper, installed in 1941 at the fork of Jericho Turnpike (NY State Route 25) and St. Johnland Road (NY State Route 25a).9 Source: LI Genealogy. It was designed by the architect Lawrence Smith Butler, who was one of Richard Smith’s descendants. Whisper is also memorialized close to this place by a vineyard named after him.

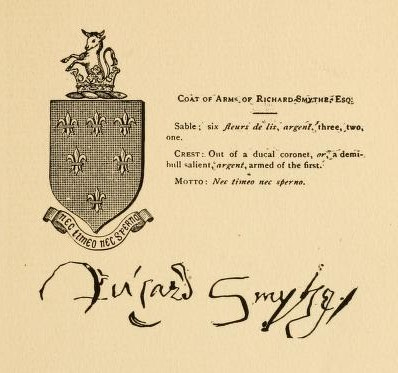

One alternate theory for the connection between Richard Smith and bulls relates to his coat of arms, which displays a bull rising out of a shield decorated with a ducal coronet and six fleurs-de-lis, symbols of royalty.

Richard Smythe’s coat of arms, signature, and motto: Nec tineo nec sperno (I neither hold nor despise). Sourced from The Library of Congress' records of the Town of Smithtown.

Other historians have suggested papal “bulls,” which were decrees issues to settle matters of church and state (often including boundary disputes between dioceses or parishes) as the relevant connection. Papal bulls were a prominent legal tool in the 17th century — but the early American colonists were not Catholic. Could Smith have issued a “Smith bull” to set the boundaries in order and end his years-long wrangling with the Dutch, the English, and the neighboring town of Huntintgton? It’s doubtful — the “bulls” were named after the “bulla” — a lead seal attached to the parchment as the pope’s own mark of authenticity.

These attempts at rationalization smell like a load of bull, and the story of Smith rescuing Heather Flower and being granted title to the land he could ride around in one day is a more appealing story. First, as I wrote above, because it offers a founding story, second, because it’s just kind of interesting.

Many people, especially Smithtown residents, dismiss these [academic] theories in favor of the fanciful fiction. It may be full of bull, but it's Smithtown's bull.10

And the third reason — whether people in Smith’s era or in our own are aware of it or not — is that it bears similarities to other ancient tales, which I will share below.

Domneva and the Cursus Cerve

Richard Smith’s legend perfectly conforms to K185.7.1. in Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk Literature: it is a “Land bargain: land surrounded by a horse (cow) in one day.” A story that puts a deer into this role puts a bit of a twist on it, for a wild-born animal is considered more difficult to control, and therefore all the more miraculous.

In my book The White Deer: Ecospirituality and the Mythic, I recount several tales from the period when Christianity was still struggling to assert itself in Pagan cultures. Often, there was a miraculous appearance of a white deer, an atavistic apparition that seemed to bestow a blessing on founders of churches and monasteries or abbeys. In cases where the deer was not white, or its color was not mentioned, it demonstrated cooperation with the legendary character’s purposes in other ways.

Domneva (aka Domne Eafe)11 came from a royal line of kings, including her great-grandfather Æthelberht of Kent, the first Christian king in England. She was married the Mercian king and had at least four children, but in her heart, she wanted to be a nun and found an abbey.

Her younger twin brothers Æthelberht and Æthelred were murdered during the reign of their cousin King Ecgbehrt by his Pagan reeve, Thunor. King Ecgbehrt agrees to pay blood money (weregeld) to prevent a feud from breaking out; however, Domneva didn’t want money — she wanted land, and she either requested or was offered as land as her tame hind could mark out at the tip-end of the Isle of Thanet in a single run.

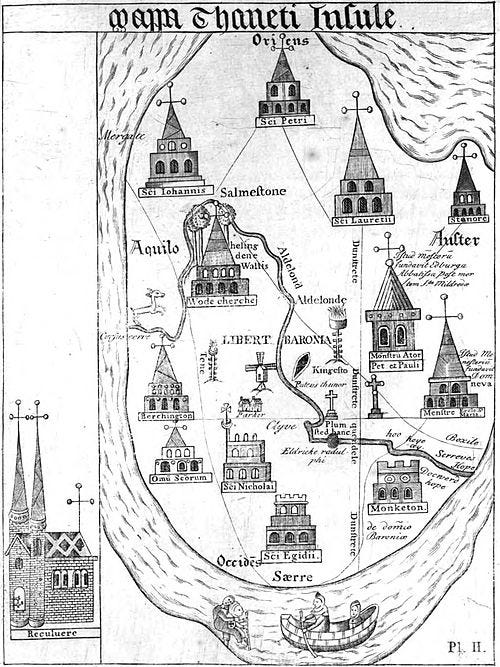

Engraving of a medieval map of Thanet with the line of the Cursus Cerve. Source: Wikimedia.

Of course, Domneva may have somehow guided the animal physically, but more poetically — as A Clerk of Oxford suggests — its actions expressed her thought or will, or perhaps it was Divine influence made the hind ran from Westgate to Minster. Whatever the case may have been, the Cursus Cerve (“deer’s way) carved out enough land for aspiring abbess to establish a dual monastery.

Later, the hind’s course was called “St Mildred’s Lynch.”

Lynch = Old English hlinc, “ridge, rising ground.” This is a hint that the hind — if it existed — was a device to reinscribe a pre-existing boundary, an ancient ridge that may have been constructed in order to separate the land belonging to the manors of Minster and Monkton. Saint Mildred was one of Domneva’s daughters, who followed in her mother’s footsteps as abbess of Minster. She is usually portrayed with a deer, the symbol of Minster-in-Thanet.

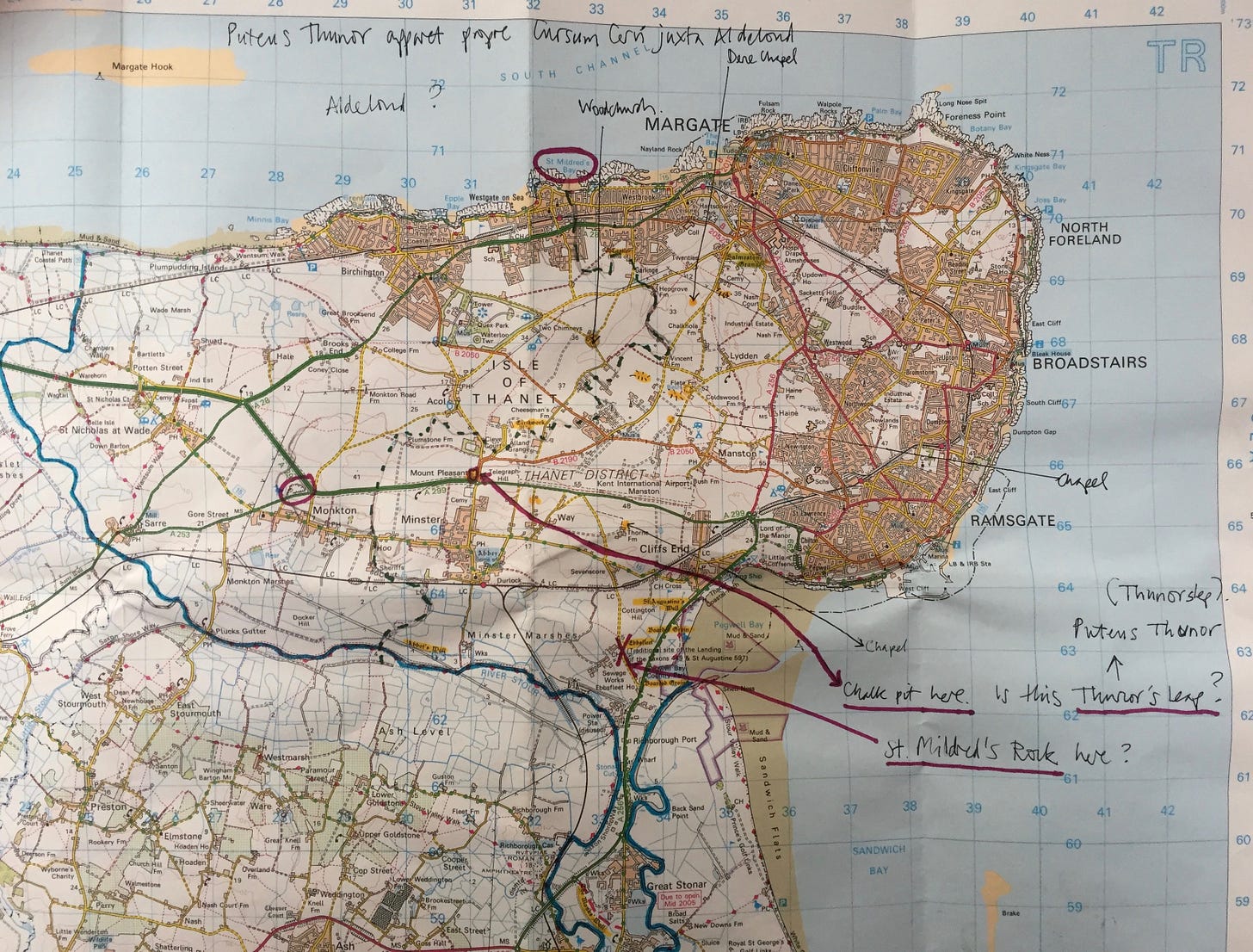

The blogger Sara Trillo made a pilgrimage to Thanet Island, where she visited the old sites and walked along the Cursus/Lynch, which she marked with a dotted line on the map below:

Read about Sara's experiences here.

The Vedic Ashvamedha

I first learned of this Vedic practice when reading Ka, by Roberto Calasso.

The Ashvamedha (अश्वमेध) was a very elaborate cycle of rituals that involved the sacrifice of many animals, agricultural products (e.g. grain, ghee), and Soma, the creation and destruction of myriad ritual and decorative artifacts, and other ceremonial acts that culminated in a dramatic horse sacrifice and taboo-transgressing ritual performed by the king’s chief queen. This tradition from the Śrauta tradition in Vedic religion was a way for ancient warrior kings to demonstrate their wealth, power, and territorial sovereignty.12

The Ashvamedha is not just a quaint legend: it is attested in many ancient texts, but over time it lost popularity and there were probably only two rulers who carried it out in the last millennium. The very last to go through with the whole cycle was Maharaja Jai Singh II of Jaipur, who conducted the rites in 1716.

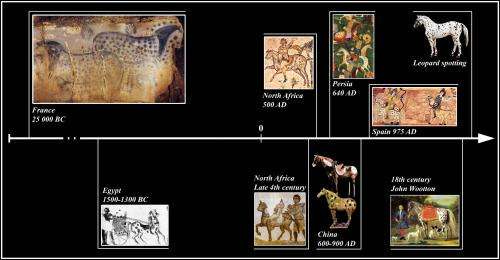

The central part, the essence of the sovereignty-enhancement that was the king’s main aim, took place in slow motion. It consisted of letting a horse wander at will around all the lands the king wanted intended to rule over, acting as a proxy for his power and ambition. The horse was not just any equine: he was a specially-selected stallion who (at least originally) had to be white with black spots. Later, artwork shows pure white stallions. However, I think the original preference for the distinctive leopard-spotted coat pattern is significant, and my speculation is that it points to very archaic roots, and therefore connects the sacrificer with much more ancient horse cults, and with the powers of regeneration he hoped to invoke through his acts.13

Oil painting of spotted horses based on work done on DNA of horse hair found in European caves by Linda Armantrout, 2011. Read about it here.

The stallion was accompanied by one hundred geldings, and a band of the king’s high-born kshatriya warriors. This entourage wandered for a year, following the horse’s whims and encountering many people along the way. All those who accepted the king’s sovereignty would honor the horse as a god, pay tribute to the king, and acknowledge that they were his vassals. Any ruler who would not accept subjugation had the chance to capture the horse and challenge the soldiers. If, after the year ended, no one had managed to kill or capture the stallion, he would be led back to the king’s seat for an extravagant cycle of festivals after which the king declared himself the unrivaled sovereign of the land.

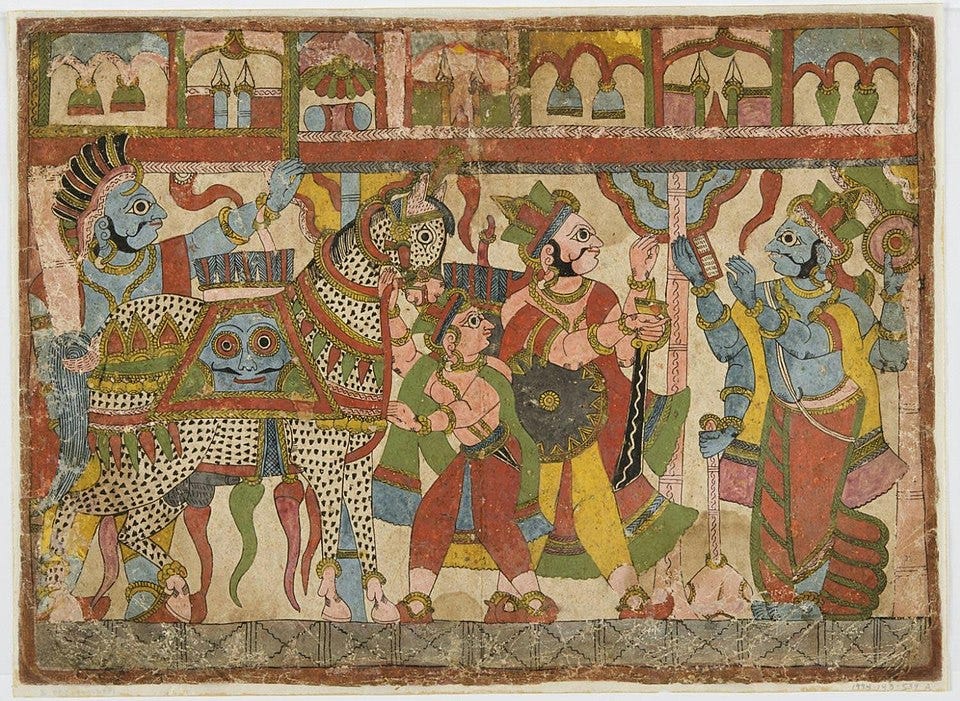

19th century painting illustrating a scene from the Mahabharata in which Krishna gives advice on the preparation of the sacrificial horse and the war band that will follow it. Source: Wikimedia.

Only a very powerful king (Maharaja) who was sure that he would prevail over all local rivals would attempt the Ashvamedha, because of the complexity of the rituals, the great expense involved, and the humiliation that would result from failure.

After astronomers decided an auspicious time to begin, preparations included the construction of a special "sacrificial house" and a fire altar. The king would spend the night before the horse was released lying awake and naked with his chief queen — but they were forbidden to have sex. Instead, the king was let tapas, the heat of desire, grow within him because, as Calasso explained, he would need this austere ardor to last for an entire year afterward.14

Before the spotted stallion was released, the king passed his sovereignty to the adhvaryu (priest), and the horse was addressed as a god: the next year would be a liminal period for all of them. Then there were more consecrations and sacrifices, and he was guided to head out in the northeast direction, free to roam where he willed for a period of a year. “Follow the path of the sky,” they told him.

The stallion’s armed contingent was tasked with keeping him alive and safe, and with preventing him from mating with mares. Like the king, he had to reserve his vital energies for other purposes. Anything unfavorable that happened to the horse (illness, injury, eye disease, or mating) would have to be compensated for with specific sacrifices, and if he was lost or died, other sacrifices were offered and he was replaced with another. While the stallion and his escort were away, the king continued performing sacrificial ceremonies and sponsoring the recitations of sacred texts and tales. People feasted and enjoyed a year of festivities in the Maharaja’s honor.

No one there was sad, no one was poor, no one was hungry, no one was unhappy, no one was rude.15

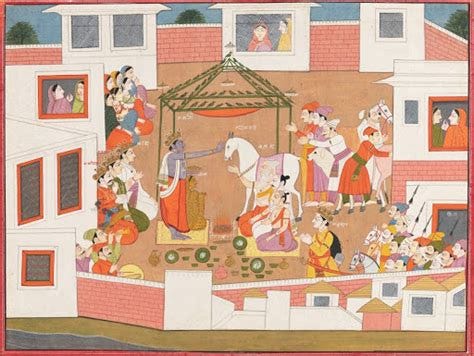

An illustration from History of India, by Romesh Chunder Dutt (1906). Wikimedia

After the stallion’s return, he was closed up in a hut, while the priests and sacrificer-king made oblations of Soma and the king chanted: “From nonbeing lead me to being; from darkness lead me to light; from death lead me to immortality.”

Within this month, other ceremonies were performed in preparation for the main sacrifice. Some of them, such as the twelve days of dīkṣā rites,16 seemed to hark back to early memories of nomadic hunting lifestyle, sinch the king would dress in a black antelope skin, and sit on another skin in a hut in front of a fire, fasting (as is common in hunters’ rites) and sleeping on the ground. After this, there were rituals in which Soma was “welcomed” and sacrificed to Indra and Agni (along with other offerings, such as barley, ghee, and domestic animals which seem to represent an agricultural and pastoral way of life). The king, his queens, and the priests would go through phases of “unpurificatory” bathing following certain animal sacrifices, then later purification rituals.

Here, you can read a detailed analysis of a painting that depicts the horse before he is sacrificed. Note the horse’s coat color, which is white, rather than spotted. I also find the (real? decoration) birds on top of the altar a charming detail.

On the twenty-sixth day after his arrival, the spotted stallion and three other horses were yoked to a gilded chariot. Verses from the Rig Vega were recited, and the horse was then driven into water and bathed. After this, the king’s chief queen, favorite wife, and “discarded wife” anointed the horse with ghee and bedecked him with golden ornaments and pearls.

Next, the sacrificial stallion, a hornless black-necked billy goat, and a wild ox were tied to sacrificial stakes near the fire. Twelve or seventeen more animals were attached with ropes tied to various symbolic parts the horse, and each was dedicated as a sacrifice to a different deity. They pulled and tugged at the horse: no longer free to roam, he was now bound in a deadly web to other domesticated animals, who writhed and pulled at him. He had been fully reintegrated into the cultural and domesticated world. All in all hundreds of animals, both wild and tame, were bound up and prepared for sacrifice.

However, there was an unexpected twist before the killing began: just when it looked when the wild animals would also be sacrificed, they were set free.

What would have happened if the wild animals had been sacrificed? “If they were sacrificed, they would soon drag the sacrificer dead into the forest, because wild animals partake of the forest.” So the sacrificer-king spared the wild animals in self-defense.17

Ambition, even ambition to complete a rite that represents “everything,” has its limits in the need of the wild to retain its own powers of sovereignty and self-regeneration.

After this, the stallion was given the remains of the previous night’s offering of grain, and then he was killed by suffocation.

The chief queen ritually called on the king's other wives for pity, and all the queens walked around the dead horse reciting mantras, and they engaged in obscene banter with the priests. The chief queen then had to spend the night with the dead horse.

There is debate on whether she was required to lie in a position that suggested or “mimicked” sexual intercourse, with the two of them covered with a blanket, or merely hold a vigil, sitting near his corpse.18 Whatever the case was, the words and deeds performed a powerful intertwining of the themes of death, fertility, and rejuvenation, and demonstrated the prerogative of the powerful to embody the essence of the law by standing outside it.

The next morning, the priests led the queen out of the place, and they recited Vedic verses calling for the horse’s healing and regeneration. The horse and the other animal victims killed along with him were dismembered and their blood was given in offerings. Three days after this, another sacrifice of Soma was offered, and a purificatory ritual for criminals and sinners was conducted.

Animal proxies

Each of the stories I have retold above presents an animal serving as a proxy that helped support the legitimacy of human claims on land, and therefore other people living on it. Other-than-human beings are perceived as more closely tied to Earth than we are, so they can intervene in what seem like purely human, or human/divine (i.e. religious) affairs, as though their authority to “speak” emerged from a separate sphere and cuts through the noise in ours.

When the world is weary of political and theological debate and discussions stall, Nature is given the semblance of a voice. It practically goes without saying that the courses taken by the chosen animals have been determined in advance, and the omens are interpreted in conformity with the wishes of powerful people. However, when the rituals are truly enacted and not only legendary tales, there is always the chance of something going awry.

Where the stories diverge is in what else besides land was being appropriated. Richard “Bull” Smith’s and Domneva’s claims went beyond mere territorial ambition. In Smith’s case (at least in the common tales that leave Lion Gardiner out), what was at stake was how an Englishman could legitimately claim land that used to be under the control of Native people.

I can’t help but be struck by the way his domesticated bull became an omen of the human and animal inhabitants that would soon dominate not just one particular patch of the North Shore of Long Island, but the entire continent.

Domneva, on the other hand, used a deer (an animal that was sacred to her Pagan predecessors and contemporaries) to put a seal of legitimacy upon her intentions, marking them as more than just her own. It is as if the old spirits of the land put their seal of blessing the churches, abbeys, and other facilities that would spread the Christian faith. As I mentioned above, I discuss quite a few other cases of this type in The White Deer.

The Ashvamedha is more complex, and it is firmly based in reality. The king-sacrificers who performed this yajna already ruled over the people around them, but in order to clinch their unassailable position and their legacy, they demonstrated that they can bring together resources ranging from a mighty war band to many craftsmen, priests and ritual specialists. Unmarried kings may not conduct yajna sacrifices, so they needed participation from their female consorts, including in ritual acts that at least suggested extremely compromising behavior. Through his actions, the Maharaja demonstrated connection with deep ancestors and the ability to command war bands, priests, farmers and cooks, and performing artists and craftspeople of all kinds. He demonstrated access to command over vast resources ranging from wild animals native to forests, mountains, rivers, underground and in the sky, to domesticated animals, food crops, and dairy animals. His priests and ritual assistants utilized the elements of fire, air (spirit), earth, and water, and they established and/or renewed connections with many, many deities and spirits through rich propitiatory offerings. The Ashvamedha is a macrocosmic event rendered at human scale.

Moreover, the Ashvamedha represents in many phases (the stallion’s peripatetics, the queen’s simulated actions) a principle pointed out by Jacques Derrida (and others): the “minimal feature” in displays that demonstrate sovereignty:

… a certain power to give, to make, but also to suspend the law; it is the exceptional right to place oneself above right, the right to non-right … the sovereign and beast seem to have in common their being-outside-the law. It is as though both of them were situated by definition at distance from or above the laws, in nonerespect for the absolute law that they make or that they are but that they do not have to respect. Being outside-the-law can … therefore take the form of the Law itself, of the origin of laws, the guarantor of laws, as though the Law, with a capital L, the condition of the law, were before, above, and therefore outside the law, external or even heterogenous to the law; but being outside-the-law can also … situate the place where the law does not appear, or is not respected, or gets violated.19

If the “beast” stands outside human society but still retains a right to speak to its affairs, it is the best possible model for the sovereign. If the sovereign (Maharaja) respects the right of the wild to its own sovereignty and self-regeneration (by letting the wild animals his hunters captured go free), he retains an endless source of power that connects him to something beyond his own ego.

We can observe an example of the opposite of this in the Wilson Diptych, which I analyze in my most popular Substack article, "White Deer As Symbols of Worldly and Spiritual Power":

This brings forward some interesting and ambiguous symbolism: the stag’s collar and chain were intended to represent Richard’s burden and responsibility of kingship, yet the animal is shown captive. The king wanted to prove that he had a divine right to rule, but that wasn’t enough, because he could not enforce his will without the help of his retainers and henchmen, who received the livery badges to pin on their outerwear. The paradox here is that the stag cannot lend Richard any legitimacy if it is already entirely identified with him, and/or in his service. In my view, that’s why the end of the chain cannot be held by anyone or attached to anything. He needed to present a higher power showing him favor. He’s not quite cheeky enough to put livery badges on Mary and Jesus, but they seem to have no objection to the angels wearing them, and they are shown obliging him with benediction in return for his homage.

The gap between the ruler and his emblems or proxies is filled with the element of manipulation and/or deception — in Richard Smith’s legend, it was him leading Whisper’s favorite cow along the desired trail the night before his ride. It was Domneva guiding or leading her pet hind around a pre-existing landwork that marked the boundary of a piece of land she wanted for herself. A king’s sovereignty is “natural” in its demonstrated effects over resources and people, but artificial in its origin claims.20

One possible escape from chaining oneself to a void is to claim that to only be moving within purely mental and symbolic realms.

This notion goes deep if we trace the etymology of Ashvamedha, which I immediately thought to do because it looks like some other words I’ve investigated. And indeed, the -medha part of Ashvamedha connects to stem words that connote wisdom, intelligence, and mental ability. Wiktionary shows us मेधा (medhā) and *men- (think, mind, spiritual activity) as roots, which give rise to a range of meanings, including to rule, to provide for, to heal, to advise, and to judge. In English, our words medicine, measure, meet, mete, mediate, method, meditate, remedy, mold, and empty also come from this root.

I traced these words out a little in an “etymological postscript” in my article Medusa, Part II - it's snakes, baby, all the way down! also in The White Deer: Ecospirituality and the Mythic, where I connect the root with scions omen, monster, and demonstrate which are useful when discussing the interpretations of unusual animals and their behavior.

There are contemporary spiritual practitioners who perform the Ashvamedha entirely in their minds. For example, the American-born spiritual teacher Adi Da Samraj speaks of his spontaneous meditative experience here. He says:

Apart from the exoteric forms of the rite, Yogis have been known to describe their Spiritual practice symbolically in terms of the Ashvamedha. In this case, the “horse” to be sacrificed is understood to be the limited self, or gross bodily awareness, which is intentionally relinquished through a process of intense inward concentration, such that the focus of attention rises to the psychic centers between the brows and above the crown of the head, resulting in subtle visions and blissful trance-states.

In its most esoteric form, the Ashvamedha is the Revelation of the Ultimate Divine Being—through the Sacrifice of everything conditional, and through the Most Perfect Realization of That which Transcends the Cosmic domain.My Demonstration of this Ultimate Form of the Ashvamedha was—and is—totally spontaneous. I Did it spontaneously, without any information in mind. Nonetheless, you will see that study of the sacred traditions confirms the truth of what I am Telling you. You have seen the True Ashvamedha Performed in My own Form.

The Ultimate Form of the Ashvamedha Transmits not merely Cosmic realization, but Transcendental Divine Self-Realization, through the Sacrifice of all conditional arising.

There are modern re-readings of the ancient texts that seem to sanitize some of the elements that give pause or cause offense to modern readers, and even — sometimes — deny that Soma was a drug. Here, we can see an example of this kind of revisionism scussions of the moral dimensions of the proceedings.

Sometimes, contemporary practitioners sacrifice an effigy of a horse in a scaled-back and purely spiritualized puja:

An effigy sacrificed at an Ashvamedha puja in New Zealand. Source.

While this may bring spiritual benefits to practitioners, it certainly cannot achieve what the Majarajas accomplished, and it cannot represent the totality of what King Richard III lamented:

”A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!”

I mostly grew up in Head of the Harbor, a village on the North Shore of Long Island. Head of the Harbor is part of the town of St. James, and St. James is part of Smithtown township. I attended Smithtown schools from K-12 before attending college and university out of state and eventually moving abroad. The Richard Smith story is something I grew up hearing about and seeing in artwork constantly.

Nissequogue means “land of clay or mud,” which suits the tidal banks of the Nissequogue River and the sometimes swampy coast of Long Island’s North Shore. The Nissequogue people, who were one of the 13 tribes of Long Island, lived east of the Nissequogue River as far as Stony Brook and from the Sound to the middle of Long Island. Here is a concise overview. All the Long Island tribes except for the Canarsies were under the authority of the Grand Sachem of the Manhassetts.

According to Puritan theology, the doctrine of God’s Providence “reached every aspect of life and warranted careful attention.” The classic work on this subject was John Flavel’s Divine Conduct, or the Mystery of Providence Opened (1678). Crucially, though, God didn’t have to do everything: the pragmatic Flavel emphasizes that sovereign control does not rule out the “use of means” — “the tools of all sorts and sizes in the shop of Providence,” which make nothing by themselves apart from “a most skillful hand that uses them.” The word and concept of Providence was used extensively by the Puritans, who were convinced that God’s assistance (Providence) to their “means” (i.e., warfare, gifts of blankets that carried illness) were the reason why the original inhabitants of the land they occupied weren’t able to effectively resist their occupation. Source.

The “Bull Smith” line of R. Smith’s descendants distinguish themselves from other Long Island Smith families, such as the “Tangier Smiths” and “Rock Smiths” who began their American story on other parts of the island. Source.

What is it about "sexy” Native American noblewomen that so captivates the colonial imagination? We’re all familiar with the “sexy” costumes, and the tropes in films and books. I think it’s because having female Native American ancestry, especially from a noble lineage, is a uniquely validating claim, no matter how spurious. The descendants of settlers who feel guilt over violence and land theft ease their minds by imagining darling, sexy Pocahontas types who welcomed their ancestors. By blending their bloodlines, they legitimized their, and their ancestors’ presence and claims on land that was almost always stolen.

Lion Gardiner was the first lord of the manor of Gardiner’s Island. Smith knew how to make enemies, but also how to make friends, and this connection was to be very advantageous for him.

According to Gardiner’s own accounts he had become a patron to Wyandanch, who was — at that time — the younger brother of the Grand Sachem of the Montaukett tribe before he became Grand Sachem himself. Gardiner had purchased an island which the Montaukett called Manchonat, located between the two forks of the east end of Long Island. Gardiner originally called it the Isle of Wight, but it was known later, and to this day as Gardiner’s Island, and his charter to it was independent of both the English and Dutch colonies.

Why would they sell him land? Gardiner was a military engineer and leader who was hired by the Connecticut Company in 1635 to oversee the construction of fortifications; later, he commanded the Saybrook Fort at the mouth of the Connecticut River during the Pequot War of 1636–37, where he took the side of the Paumanacke tribe and their allies against the Pequot.

Later, Gardiner was given the lands that would eventually be sold to Smith and become known as Smithtown as a gift for his support to tribes that were in danger of being wiped out by their enemies.

Above: a watercolor of Lion Gardener defending the Saybrook fort during the Pequot War. Based on a drawing by Charles Stanley Reinhart, ca 1890. Wikimedia.

This is the text of “Wyandank’s Deed to Lion Gardiner, of Smithtown. East Hampton, July 14, 1659.

Bee it Knowne unto all men, both English and Indians especially the Inhabitants of Long Island that I Wyandance Sachem of Pamanack, with my wife and sonn Wiankanbonem, my only sonn and heir, havinge delyberately considered how this twentie-four years wee have bene not only acquaited with Lion Gardiner, but from time to time have recived much kindnes of him and from him, not onely by counsell and advice in our prosperitie, but in our great extremytie, when wee were almost swallowed upp of our enemies, then wee say he apeared to us not only as a friend, but as a father, in givinge us his monie and goods, whereby wee defended ourselves, and ransomed my daughter and friends, and wee say and know that by his manes we had great comfort and reliefe from the most honorable of the English nation here about us: soe that seigne wee yet live, and both of us being now ould, and not that wee at any time have given him anythige to gratifie his fatherly love, care and charge, we havinge noting left that is worth his acceptance but a small tract of land which wee desire him to Accept of for himself, his heirs, executors and assignes forever, now that it may be knowne how and where that land beinge Cowharbor, easterly Arhata a munt, and southerly ercrosse the Island to the end of the great hollow or valley, or more than helf through the Island southerly; and that this gaft is our free act and deede: sealed and delivered in the presence of Witnes: Richard Smith, Thomas Chatfield, Thomas Tallmmage, Wayandance his(88)mark, (etc.) The text is available here.

Source of the above theories: Molly McCarthy, Newsday.

Domneva / Domne Eafe was not this woman’s given name. Domne is the local version of the Latin domina, which is a title, and Eafe could be a local version of the name Eve, but it could also be a garbled version of Æbbe or Ebbe, which is Abbess — also a title rather than a name.

Brahminical Hinduism insists on giving only vegetarian offerings, which eventually became the norm for Indian religion; however, the Ashvamedha persisted as long as it did because of its great prestige and political importance.

The “bloodless” killing of the horse by suffocation may have been a nod to these evolving sensibilities, but the dead horse’s organs and blood were still used in offerings the day after it was sacrificed. In earlier eras of Indian history, of course human sacrifice had also been known. Source.

Interestingly, the way the horse is killed was by closing up its nostrils, eyes, and ears with a linen cloth — it is suffocated. I immediately thought of a practice done by yogis, not using fabric, but their own hands, in which they close their eyes, nose, and mouth — this is called yoni mudra. Mudra is a holy gesture, and yoni is the vagina/womb. The name stems from the belief that the temporary, mild state of sensory deprivation it induces harkens back to the embryo’s life in the womb. In this condition of freedom from the constant bombardment of the senses, it brings about Pratyahara, a virtuous withdrawal of senses and consciousness from the external world — essential conditions for practicing meditation and, eventually achieving samadhi. Benefits of practicing yoni mudra may include perceiving ever more subtle and sublime sounds and inner light, awakening the kundalini, and even “the destruction of all sins.”

The best-known text describing the sacrifice is the Ashvamedhika Parva — the "Book of Horse Sacrifice," the fourteenth book of the epic poem Mahabharata. In this volume, Krishna and Vyasa advise King Yudhisthira to perform the sacrifice, which is described in great length and detail.

Let’s put this geekery into a footnote, shall we?

Leopard-spotted coats — perhaps — originated more than 20,000 years ago. This paper and this one discuss how the original gene arose from an alteration caused by a retrovirus in the Pleistocene era.

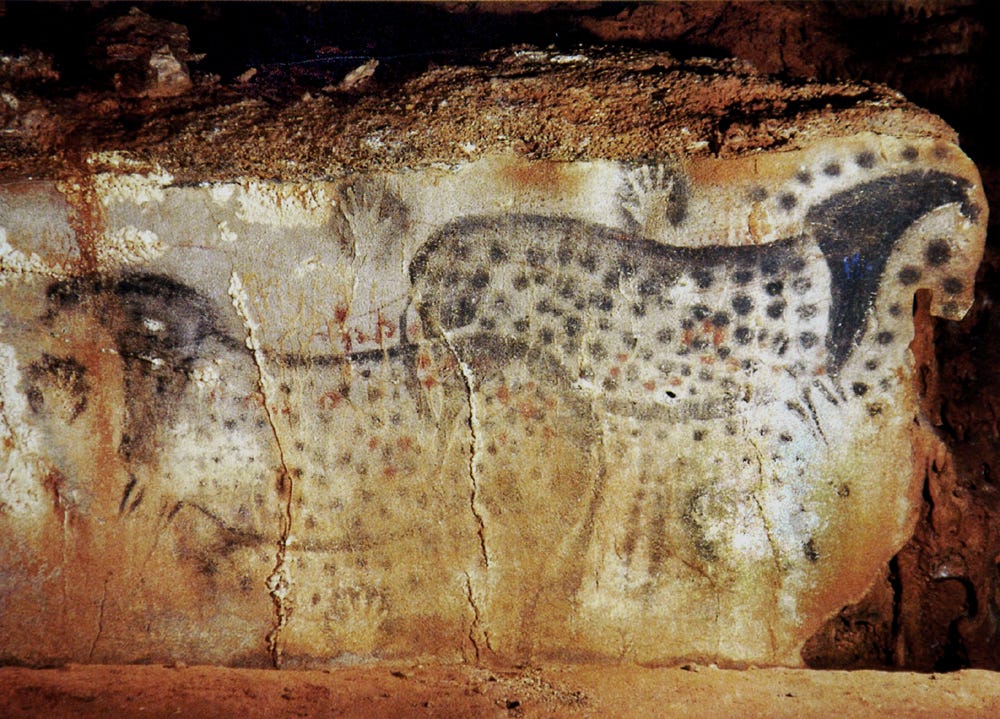

We can see human illustrations of horses with the leopard spot/night blindness mutation in the Pech Merle cave in France. The cave’s walls are decorated with paintings and engravings made by artists ranging from the Gravettian culture around 25,000 BCE, through the Solutrean roughly 18,000 BCE and the Magdalenian era, about 15,000 BCE. Their artworks were only discovered in 1922.

The panel illustrating spotted horses is probably the most famous painting in Pech Merle. You can observe typical Paleolithic use of natural stone formations to give shape and dynamism to the images, but also the hand stencils that leave a trace of the artists’ presence. However, even more interesting is that the horses’ spots do not only remain on their skin — they seem to have a life of their own, outside the lines (!!!)

Image source: Bradshaw Foundation.

Later, leopard spots were artificially selected for by human horse breeders in the earliest era of horse domestication, then selected against in the Bronze Age. Why did the Ashvamedha ritual require a stallion with this kind of coat? If the people performing the sacrifices had an awareness of earlier preferences, it could have been seen as a connection with ancestral people who preferred this marking, and the horse as a sacrificed messenger could intercede with them and bear their blessings upon the sacrificing king’s claims to sovereignty.

Calasso also has a beautifully poetic description of how the entire Ashvamedha is built from nothing, and leaves nothing at the endXXX133

See Calasso, p. 132.

Diksha were rites of preparation or consecration/transmission. The word is derived from the Sanskrit root dā [to give] and kṣi [to destroy], or alternately from the verb root dīkṣ [to consecrate], and someone who is undergoing such preparations must commit to practicing rigorous spiritual discipline. Wikipedia.

Calasso, p. 141.

Here are some discussions that include proponents of both sides of the debate, which refers to ancient texts and claims that one side is reproducing colonialists’ misreadings of the text that highlight its exotic, and barbarous elements, while the other side is sanitizing ancient fertility rituals to suit modern sensibilities.

The animal sacrifices are also called into question by contemporary Hindus in certain traditions; some of them insist that the Ashvamedha is only an allegory in which bloodless rituals were performed to connect a practitioner with their “inner sun” (prana). However, given the wealth of historical evidence from Sanskrit epics and Puranas to ritual instructions and coins depicting horses tied to sacrificial posts and the names of kings who had performed the yajna, this seems like wishful thinking or less-than-honest apologetics. Also, since the cycle of rites, which lasted over a year, were conducted in a very public manner — their nature as a seal of certification over a king’s right to rule meant they could not be solitary and private and have such great impact and prestige attached to them. Among the many other purposes and effects of the Ashvamedha was a great deal of redistribution of wealth from the king to the population.

I mentioned in Footnote #12 that evolving sensitivities about sacrifices led later readers of texts that describe the Ashvamedha to suggest that everything that happened was only metaphor. At an earlier time, however, the prestige of the Ashvamedha was so powerful that any Brahmin who claimed not to know about the rite (i.e., refused to acknowledge its legitimacy) could be legally robbed and humiliated. (See Calasso, p. 137.)

Calasso describes the queen’s time with the dead horse in quite a lot of lurid detail, and he provides references. It is, however, beyond my scope of possibility here to make determinations on whether the translations from Sanskrit he was using were contaminated with colonial prejudice or accurately reflected the ancient texts so I’m taking an agnostic view on how the queens may have behaved, especially since it probably changed over time, and differed in actual individual instances of the rite’s performance.

Derrida, Jacques. The Beast & the Sovereign, Vol. I. Trans. Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 16-17.

See Derrida, p. 28, for a discussion of sovereignty in Hobbes’ conception. “This sovereignty is like an iron lung, an artificial respiration, and ‘Artificiall Soul.’ So the state is a sort of robot, an animal monster, which, in the figure of man, or of man in the figure of the animal monster, is stronger, etc. than natural man. Like a gigantic prosthesis designed to amplify, by objectifying it outside natural man, to amplify the power of the living, the living man that it protects, that it serves, but like a dead machine … this prosthstate must also extend, mime, imitate, even reproduce down to the details the living creature that produces it".

On p. 30, he recalls the adage Homo homini lupus, “man is a wolf to man” as a guiding principle for these reflections.

stories and images for good and right-on dreams