The first article in this series introduced a festival honoring the goddess Diana at her sacred grove at Nemi; the second discussed the still-living legacy of the Rex nemorensis. Now we'll meet the enigmatic spirit that enlivens fields, language, and writing, and makes the world more haunted, more fertile, and more alive.

If you like these kinds of reflections, subscribe so you won’t miss anything.

The corn dog and the corn wolf

Ah, the corn dog — what could be more American than this salty, fatty, highly processed artifact of industrial agriculture and the food processing and logistics industries, dipped in oil and usually served hot at fairs, carnivals, and other outdoor events?

“Pronto-Pups” are a particular brand of corn dog, particularly beloved in Minnesota.

But what is the corn wolf?

I painted this image of the Corn Wolf with watercolor pencils and gouache.

This enigmatic spirit belongs among those classified as Feldgeister (field spirits) or sometimes Korndämonen (corn demons) in German folklore. James George Frazer's account of the Corn Wolf is very beautifully and evocatively written, and captures some of the diversity in the forms they take and how people relate to them. Sometimes these spirits take the shapes of domestic or wild animals,1 including sheep, horses, deer, rabbits, foxes, mice, various kinds of birds, or even dragons. Other Feldgeister such as the Katzenmann (a cat man who shares feline and human features) and human-goat hybrids, have mixed human and animal features. When their appearance is human with some demonic elements, they may be of either gender, according to type. Some of them also look like children, or they are interested in stealing human children, perhaps replacing them with changelings.

They dwell in cultivated fields, but then at harvest time, they flee from the reapers cutting sheaves of grain, retreating until they are left trapped in the last stalks.

Herman Winthrop Peirce, The Last Sheaf (1884). What will she do with it?

Feldgeister can have good or ill intent toward people, but the relationships between the people, the crops, and the spirit has to be handled carefully, because direct contact with the spirit was believed to cause illness. Often, field spirits required sacrifices; in other cases they needed to be provided with a place where they could dwell after the reapers destroyed their home; in still others, the field spirits’ abode was a place for negotiating with other beings that had the power to help or harm farmers — birds.

Channeling the field spirits’ power toward the purpose of ensuring fertility while also avoiding offending or harming it was a great responsibility. Some traditions prescribed fashioning the last stalks of grain taken from the field, and which contained the spirit within them, into a corn “dolly” in the shape of a human or of a wolf that was carried into the village.2 Someone then had to take it in and keep it as a guest through the winter. Then, when spring came around again, the corn dolly might be plowed back into the field.

Quaint, isn’t it? Frazer suggested these customs were a grim reminder of times when a human being was sacrificed for the sake of the fields’ bounty. We may not believe that would be a useful way to keep the fields productive, and we may not even believe that real human sacrifices took place every harvest season. But the dying/rising deity motif has been persistent in European, British, and Eastern Mediterranean culture for millennia: Dumuzi, Osiris, Persephone, Jesus, John Barleycorn. The importance of this figure in both ancient and contemporary cultures can hardly be overstated, as I discussed in the previous article in this series.

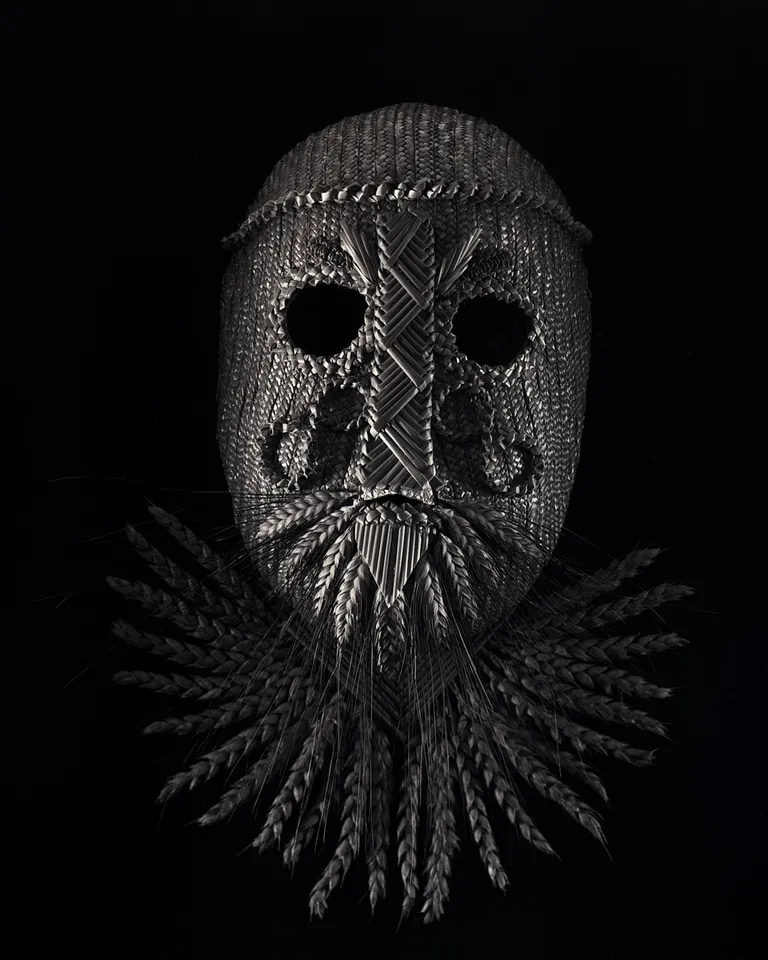

A mask made by Matt Rowe, from the exhibition John Barleycorn Must Die (2019).

3 x 3: three triplicate aspects of the corn wolf

The corn wolf isn’t simply a tricksy nature spirit — it is a figure that encompasses complex and deeply ambiguous mythology and cosmology. The three aspects or sites of the corn wolf presented by J. G. Frazer that were commented upon by Ludwig Wittgenstein and by the contemporary anthropologist Michael Taussig are:

That which is had been present throughout the crop but ends up hidden in the last sheaf of corn (i.e. any grain) harvested

The last sheaf itself, which is left standing

The reaper who binds the last sheaf

The Dress, by Lou Benesch. While it was probably not the artist’s intention to illustrate the aspects of the Corn Wolf in this painting, I find that it serves the purpose nicely.

As I described in my previous article, "The king is dead - long live the King!" Ludwig Wittgenstein was a very critical reader of Frazer. He considered Frazer a modern “savage” with a narrow spiritual life, and, in accordance with his own religious convictions, he disparaged the anthropologist’s project of comparing Christianity with so-called primitive religions and relegating all of them to the category of historical illusions. He wanted there to be “higher” values than Frazer’s reductive scientism, but he was at a loss to define them.

The flummoxed philosopher reworded and reordered the reflections which were later collected as the Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough many times, using the help of a typist who took dictation. However, there were also some comments he wrote using a pencil on odd scraps of paper, and these were never dictated to the typist because they betrayed some of the unresolved tensions in his thinking about the Corn Wolf. He marked these remarks with an ‘S’ for schlecht (bad), but he still held onto them among his private papers. They were probably inserted into his one-volume edition of The Golden Bough and were found among his things after his death.3

I now believe that it would be right to begin my book with remarks on metaphysics4 as a kind of magic. Where, in doing so, however, I must neither speak out for magic, nor ridicule it. The depth of magic ought to be preserved. — Yes, here canceling out magic has the character of magic itself. For when I began earlier [i.e., in a prior work] to speak about the “world” (and not of this tree or table), what else was I attempting than to conjure up something higher in my words.

Metaphysics is similar to magic because both rely on posited truths and on images and concepts, and neither metaphysics nor magic can be tested and verified in any systematic way because the essences they work with are ineffable, so no method of comparison can be defined. (And in the case of Christianity, tempting or testing God is actually taboo.) Of course, it isn’t really possible to think or use language without some degree of metaphysics — and vice versa.5

Paradoxically, the phrase “metaphysics is a kind of magic” seems to reveal exactly the kind of evolutionary model Wittgenstein disparaged in Frazer’s work; i.e., a development from primitive superstition to religion. He admits in Remark No. 24 that “A whole mythology is deposited in our language,” which indicates awareness of the inherent metaphysics within language. However, when he compares the polysemous Corn Wolf with ordinary operations of language that everyone is familiar with, he strips it of its magical status and accommodates it to mundane life in a way that hollows out the “depth” that he declared he wanted to preserve.

”And when I read Frazer, I keep wanting to say at every step: All these processes, these changes of meaning, are still present to us in our word language. If what is called the “corn-wolf ” is what is hidden in the last sheaf, but [if this name applies] also to the last sheaf itself and the man who binds it, then we recognize in this a linguistic process with which we are perfectly familiar.”6

I believe his choice of verb in Remark No. 17 was not accidental: “We must plough over language in its entirety,” nor was it likely to have been subconscious. But where does that leave the Corn Wolf if there is no last sheaf standing, and no one has taken her home for the winter?

(Poor wolf! If the whole field of language has been ploughed, she has lost her home and must be very sad.)

Here’s my attempt at an alternate formulation of the triple mystery of the Corn Wolf. It would be unacceptable to Frazer and Wittgenstein alike, because it opens up spaces for the magic to dwell in and to operate from — it arises out of a more animist conception.

The mystery of the land’s fertility [an eternal aspect, which, is experienced by those who participate in myth, as a mysterious, metaphysical given; the myths, themselves, evolve with experience]

The tabooed abode of this mystery: the last sheaf, the corn dolly, or the scapegoat [artifacts that exist within time and space and can be perceived by the senses]

The person responsible for stewardship of the abode; or, in some cases, those who organize the sacrifice of the scapegoat designated to take away any potential future misfortune [the active principle]7

My model could serve as a minimal framework for applied animism, but I’m not going to pursue this right now.

A third “trinitarian” model that could also be applied is Jacques Derrida’s concept of the pharmakon. This term, which he took from the Greek φάρμακον (phármakon), refers to all of the following:

remedy

poison

For example, pharmakon is the word used for the hemlock drink that caused Socrates’ death, “healed” the society that had condemned him (by making him a scapegoat), and also brought him immortality. However, Derrida, in his interpretation of Plato, was not talking about potions and philtres: his discourse was instead about writing, which also has all three of these qualities and is similar (though not identical) to it.8 This is a theme I will revisit at the end of the essay, and which I’ll explore further in a piece I’m working on now that will offer guidance to those writing fiction and nonfiction that takes readers to strange, haunted places.

The Stars, by Lou Benesch. Find more of this artist’s work at This is Colossal, on Booooooom, or on her own page.

Personal and personified relationships with the land

We can see echoes of cosmologies similar to the Corn Wolf mythos in other folktales and customs. For instance, late survivals of the motif of farmers cultivating respectful reciprocal relationships with spirits of the land are present in some of the folktales collected by the German folklorist Franz Xaver von Schönwerth in the mid-nineteenth century. Some of the more than 500 tales he collected have been translated into English and published in the volume The Turnip Princess.9

One of the best examples of a human/supernatural partnership is found the story “The Little Flax Flower.”

Here is my abridged retelling:

There were once two marriageable young women: one was pretty and vain, and the other was plain and hard-working, and they spent their days in the fields sowing flaxseeds. The pretty one worked in the hills; the plain one, in the valley. One day, while they were walking behind a plow, the pretty one began to sing frivolous songs about her longing to wed a beautiful man. The plain girl kept quiet, and every once in a while she would toss a few flaxseeds aside for the Lady of the Woods.

When it was time to weed the fields, the pretty woman spent most of her time looking around to see if any suitors had noticed her yet; the plain one was quick about her work and soon cleared away all the thistles and weeds. She did not neglect to take a few stalks of flax and make a little hut at the edge of the field. When she had done this, she called out:

”Lady of the Woods, the Woods, the Woods,”

Here I’ve placed your share of the goods!

Give the flax a nice good start,

And let’s dress up so we look smart.”Needless to say, the hardworking woman continued to put her best efforts into the work of spinning and weaving her flax, and then bleaching their linen cloth and making beautiful clothing, while the pretty woman shirked her tasks. The pretty woman was upset at the difference in their results and scolded her: “I know just how you did this, you little night owl! You’re a witch and you were in cahoots with the Lady of the Woods. You’re just as plain as she is, and just like that forest spinster,10 you’ll never marry.”

Of course, this is not the way the story ends: a prince arrives, and he is so impressed by the diligent farm girl that he married her, and her envious companion suddenly became as hideous as a toad.

The story ends like this: “Since then the young women who work in the fields no longer sing songs. And not a one forgets to bind together some of the flax stalks from the fields and make a little hut for the Lady of the Woods. They remain faithful to the customs from times past.”

Where I live, in a rural part of the Czech Republic, it is common to find little homes for elves or fairies in the woods. Children make them using various natural materials that they find near their site. Learning to make these houses seems to be a key part of their early education, and nursery school teachers and parents will help the kids find materials and construct the little houses and garden elements.

Land “given over” and the mystery of offerings in Bali

Most people are familiar with the concept of crop rotation, in which different kinds of plants are grown in fields in successive years, and then the land is left fallow to recover.

Less familiar is the habit of dedicating a piece of land to land spirits or to their master. Some of the names for this “given ground” include the Gudeman’s Croft, Halyman’s (Holy Man’s) Croft, the Goodman’s Fold, the Gi’en Rig (Given Rig or the Given Ground), Devil’s Croft, Clootie’s Croft, and the Black Faulie (the Black Fold). A farmer who set this land aside for a supernatural being expected it to bring certain benefits, but often of an unexpected nature — it was an act of trust in the reciprocal relationship.

Folklorist and occult researcher Robin Artisson has dug deeply into trial records and other documents created when an elderly Scottish cunning man and healer named Andro Man was accused of witchcraft.11 Robin was kind enough to share the excerpt from Andro’s trial records where he tells how he consecrated ground to a being he usually called Christsonday, but also referred to as the Gudeman or the Hynd Knight:

“Thow hes mett and messurit dyvers peces of land, callit wardis, to the hynd knicht quhom thow confessis to be a spreit, and puttis four stanis in the four nokis of the ward, and charmes the samen, and theirby haillis the guidis, and preservis thame fra the lunsaucht and all vther diseasis, and thow forbiddis to cast faill or divett thereon, oir put plewis therin ... ”

“You have measured and squared many different pieces of land, called wards, (dedicating them) to the Hynd Knight whom you confess to be a spirit, and put four stones in the four corners of the ward, and charmed the same, and thereby draw in the good, and preserve them from lung disease of cattle or men, and all other diseases, and you forbid that anyone cast earth or turf on the ward, or put plows therein … ”

Andro Man never admitted to harming anyone — the magic he used as a cunning man was always intended to bring benefit to someone. However, he had the misfortune to be alive at the wrong time and place — during what historians would later call the Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597; the second of what would eventually be five “Great Scottish Witch Hunts.”

The spirits Andro Man consorted with were classified as the Devil and demons, and he was pronounced guilty of witchcraft and, ultimately, sentenced to be burnt. Like the hard-working woman in “The Little Flax Flower,” Man was accused of associating with the worst sorts of beings by those who had little understanding of the subtle powers that fecundate the land and suppress pests and diseases.

What they failed to appreciate was that a piece of “given ground” is a kind of private sanctuary that supports biodiversity, and provides shelter for a multitude of beneficial species, such as birds, hedgehogs, bats, foxes and martens (which eat rodents), helpful insects, mycelia that are harmed by plowing, and the plants and trees that support them.

And yet, reductive biological explanations don’t entirely encompass the field of intertwined relationships on a piece of shared ground. The American ecologist and philosopher David Abram writes very movingly on the interrelationship between a magical agent and the other intelligences operating in his vicinity.

When he lived in Bali, he was astonished to find people putting out tiny platters of food as offerings for “the spirits,” and was even more perplexed when he saw that the food was carried away by ants. Didn’t the people know their offerings were being “stolen”?

… The idea became less strange as I pondered the matter. The family compound, like most on this tropical island, had been constructed in the vicinity of several ant colonies. Since a great deal of household cooking took place in the compound, and also the preparation of elaborate offerings of foodstuffs for various rituals and festivals, the grounds and the buildings were vulnerable to infestations by the ant population. Such invasions could range from rare nuisances to a periodic or even constant siege. It became apparent that the daily palm-frond offerings served to preclude such an attack by the natural forces that surrounded (and underlay) the family’s land. The daily gifts of rice kept the ant colonies occupied–and, presumably, satisfied. Placed in regular, repeated locations at the corners of various structures around the compound, the offerings seemed to establish certain boundaries between the human and ant communities; by honoring this boundary with gifts, the humans apparently hoped to persuade the insects to respect the boundary and not enter the buildings.

The ants probably could have invaded the people’s dwellings, and the people could have responded with more and more aggressive forms of retaliation, but the pact seemed to hold.

Sheaves and birds

Swedes traditionally put aside the last sheaves of grain from the harvest and hung out a bundle for the birds on Christmas (called a julkarve), hoping the birds would stay out of the barn where their harvest was stored.

Norwegians call the same sheaf a julenek, but instead of just hoping the birds will leave their grain stores alone, they are focused on achieving plentiful harvests in the next season: they believe that if many birds come to eat they’ll bring in a good crop the coming year. (Which is a reasonable assumption, considering that many birds are omnivorous and eat insect pests during the warm months.) The sheaf might be hoisted on a stake or placed high in an apple tree, with petitions to the spirit of the harvest to be generous with the family.

Naturally, besides attracting beneficial creatures the very act of offering a small part of the harvest with the birds is a significant reminder that, no matter how lean the times, people must share in order to survive and thrive. Originally, julkarve weren't intended to be aesthetically pleasing — farmers simply bound up a barrel-size sheaf and hung it up — but over time they've developed into decorations with the sleek elegance for which Scandinavian design is known. If you’d like to make one yourself, instructions can be found here.

Feldgeister at large and grain as pharmakon

When land is depleted by never-ending planting cycles; when monocultures rob the soil of nutrients and even make the bees sick, we begin to reap the crop of a very dark pact humanity has made — with technology. Taussig writes: “In an age of agribusiness and global warming, of environmental revenge following attempts to master nature, it is worth thinking about the disappearance of the vegetable god and its sacrifice. In the supermarket there is no last sheaf.”

Sheaf of Grain, by Franz Marc (1907)

Just as there is no actual last sheaf of grain, today there is also no responsible party, no final reaper, and no host for the corn dolly. The three aspects of the Corn Wolf I identified in my model: the eternal aspect experienced by those who participate in myth; the artifacts; and the active principle are all missing. Responsibility has now become generalized to “stakeholders” — a broad yet meaningful category that includes anyone affected in any way by the impacts of agribusiness activities, and who are (supposedly) empowered to provide meaningful feedback to the system, but who are mostly, in fact, its victims. It is only a narrow class of these “stakeholders” — the shareholders of corporate stock, who must be continually fed with offerings.

Spiritual danger, illness, and contagion are very slippery — the topic of how they are move and spread has been analyzed at length by many anthropologists and philosophers, such as Mary Douglas and René Girard, to name two. In the old German folklore, direct contact with Feldgeister was said to cause illness; thus, all the customs treated the last sheaf as something that could equally bring boon and bane.

Grain itself is also pharmakon. It nourishes us, but also poisons us in several ways. It’s fairly well known by now that excess consumption of grain has harmful effects on the human body; a fact that our way-distant ancestors who were making the transition to full-time agriculture were aware of. And it also, historically, has led to social stratification and accordingly, depending on the time and place, to warfare: the plough and the sword are two differently-sharpened sides of the same rod of metal, and the one can always be refashioned into the other.

And grain, as Frazer tirelessly reminded us, and as can be traced through myths retold in the Bible (which I discuss in my book The White Deer), always requires sacrifices. By sacrifices, I don’t only mean agricultural inputs: human labor, petrochemicals, and land that might be used for other purposes, but also a diminishment of human flourishing in both the physical sense and the social sense mentioned above.

When the Corn Wolf is domesticated into corn dogs, sacrifices are extracted from all those eating the corn dogs, hot pockets, and frozen dino-shaped reconstituted chicken — and from their children and descendants to the nth generation — not only because of the ill effects on their health,12 but also because the tilth, the water, the air, and many, many species have been killed or replaced with monocultures and livestock.

Like fungi, the spirits of the land cannot be killed in ways that matter, nor can they be vanquished or driven away forever. While the old taboos respected their power to cause harm, now they have slipped their bonds and agribusiness spreads the mischief everywhere. Folk customs and considerations that there should be a last sheaf, a fallow corner of the field, a hedgerow, and a little goodness left over for the mysterious forces that help the fertility of fields and gardens are abandoned at our peril.

Making “sacrifices” that give something back to the Earth (e.g., letting fields lie fallow, using compost and manure, creating hedgerows and windbreaks, planting companion crops together, etc.) is part of a mindset that fosters more health for the land, people, and all other species.

A well-stocked Walmart.

Michael Taussig and three styles of writing

I found Michael Taussig’s delightful collection of essays titled The Corn Wolf by accident. You see, I’ve been researching a project on wolves.13 In the process of hunting and gathering materials, trying to pull in anything that might possibly be useful, at some points I simply put “wolf” or “wolves” into browser searches, or on pages that curate scholarly literature and looked at what came up. You could call this a form of bibliomancy — enhanced by Google. A walk in the Groves of Symbols carrying a game bag. Or perhaps applied “literary ecology”:

Everything points to something not itself. This would be a good first definition of ecology.14

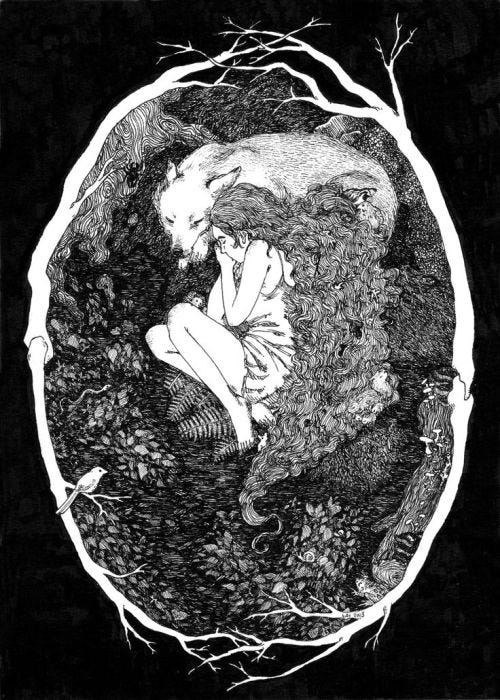

I Was Raised in the Forest, by kAt Philbin

As you can now guess, The Corn Wolf isn’t about wolves, but I have long been an admirer of Taussig’s so his name was the second reason the book drew my attention. What I found in this delightful volume fascinated me in a different way than his other works: it’s a manual for writing and for living. It’s also a style of literary criticism and it offers guidelines for those doing and reading ethnography. I’ve been reading and wrestling with the material for the last three months, and it was the impetus for what became the trio of essays I’ve published this month — but I’m still not done working with it.

Anyway, in the first essay in the book, titled “The Corn Wolf: Writing Apotropaic Texts,” Taussig distinguishes three styles of writing:

Agribusiness writing

Nervous system writing

Corn wolfing

Agribusiness writing does not consist of farming manuals and other such practical information. It’s a metaphor for a mode of production that assumes that writing itself is a means — and not a source — of experience; it’s “content” that can analyzed in “metrics” instead of art, literature, or storytelling; it’s AI-written text; it’s the outputs created by the “publish or perish” paradigm in institutes of what used to be called higher learning.15 Agribusiness writing exudes the deceptive and poisonous aspect of Plato’s pharmakon, and it is undergirded by fear. Taussig cites Nietzsche’s argument in The Gay Science that we generally reduce the unknown to the known because of our fear of the former. Agribusiness writing therefore “knows no wonder,” and “wants mastery, not the mastery of non-mastery.” But, even worse, this procedure “conceals how strange is the known” because it finds itself unable to estrange its own nature.16

In his Dark Ecology, which analyzes the logic of agribusiness in fascinating depth and makes a fine companion to Taussig’s Corn Wolf, Timothy Morton points out that “agrilogistics” seeks to flatten out all twists (the ones that loop from the known to the unknown, and back again). It then attempts to close the former open Moebius strip into a circle that circumscribes the knowable and controllable, while excluding doubt and mystery. Of course, this is impossible, yet no degree of failure has sufficed to make people radically rethink the strategy wherever it has taken hold. On page 53, Morton tells us: “Agrilogistics was a disaster early on, yet it was repeated across Earth. There is a good Freudian term for the blind thrashing (and threshing) of this destructive machination: death drive.” And: “The attempt to transcend the web of fate ends up doubling down on it: it is the web of fate, the very form of tragedy” (p. 89).

Roland Barthe said codes cannot be destroyed, only “played off” — engaging in nervous system writing is an attempt to keep ahead of the chaos and anomie, but one already knows beforehand that it is doomed. It is a game of “writing that finds itself implicated in the play of institutionalized power as a play of feints and bluffs and as-ifs taken as real in which you are expected to play by the rules only to find that there are none and then, like a fish dangling on the hook, you are jerked into a spine-breaking recognition that yes! after all, there are rules … ”

This is the mess you get into when you try to engage with the sites of worldly power and all their absurdities. Taussig spent his entire career trying to bring forward the voices of those who have been under assault and lost their homes due to agribusiness, corrupt governments, paramilitaries, and drug lords. The Nervous System he describes is the absurd power of totalitarian regimes and of corporatocracy. It is power usurped from the people for any spurious reason that holds on with iron claws and metastasizes — because that’s all it ever intended to do. I’m sure we can all think of some more examples of this.

Nervous system writing tries to bring a new order from outside the system, but it is co-opted and assimilated, so the effects it causes within that environment are counterproductive or even parodic. What is observed and reported by a sincere actor in a nervous system cannot be place anywhere that it can exert leverage.

“ … think of a Cubist drawing with its intersecting planes and disorganization of cherished Renaissance perspective. Think of a person changing into a jaguar, at least from the waist up …

[attempting to set records straight and bring violent actors to accountability is in vain because] … worst of all, none of the motives made sense, leaving just violence, a nervous system … so many hearts of darkness and the ultimate violence was giving the Nervous System its fix, its craving for order, at which point it would spin around, laughing at your naivete, because the more order you found, the more you jacked up the disorder.”

Taussig had serious types of disorder in mind when he wrote this. A trivial example of acting within a nervous system is me attempting to get this article noticed on Facebook by posting a selfie where I wear an unusual color of lipstick, because that’s what the platform wants me to do in order for them not to suppress my content. That, or show them my lunch or my animal companions. Maybe I’ll do that next time.

This adds nothing of value to my essay, but it gives the Facebook Nervous System its fix of “order.” They reward such stunts because they want to maximize the content they feel other users (i.e. my friends and family) want to engage with. For those who would like to try this at home, it’s not really lipstick — I used green eyeliner on my lips this photo, and in the other selfies that were my most popular Facebook posts over the past year I used dark grey.

Yet, there is a third way to approach hegemonic, metastasizing systems.

In Act Seven of this essay, Taussig tells us:

Corn wolfing moves include the following:

Refusing to give the Nervous System its fix of order.

Demystification fine as long as it implies and involves reenchantment …

The recognition that while it is hazardous, idiosyncratic, and mystical to entertain a mimetic theory of language and writing, it is no less hazardous not to have such a theory. We live with both things going on simultaneously. This absurd state of affairs is where the Corn Wolf roams. Try to imagine what would happen if we didn’t in daily practice conspire to actively forget what Saussure called the arbitrariness of the sign. Or try the opposite experiment: Try to imagine living in a world whose signs were “natural.”

That we destroy only as creators, says Nietzsche. What he means is that in analyzing and interpreting we implicitly build culture itself. And nowhere will this be more pertinent than with anthropology — the study of culture. But what is also meant is the blurring of fiction and nonfiction, beginning with the recognition and appraisal that this distinction is itself fictional and necessary. That too is a Nervous System, the endorsement of the real as really made up. The ultimate wolfing move.

Act Eight

But are we capable of wolfing the wolf? For as the sun goes down, as if forever, are we today not the last sheaf? And who will bind us? Truly the mythology is one jump ahead. For as the world heats up, thanks to agribusiness, it is possible that subjects will become objects and a new, which is to say “old” constellation of the body to soul will snap into place in which writing will be neither one nor the other but both, in the Corn Wolfing way I have described in the previous act, the one permanently before the last?

Illustration by Laurel Long from The Magic Nesting Doll, which is a very corn-wolfy story.

The current buzz among anthropologists critiquing Wittgenstein’s approach to Frazer is a continuation of over a half century of critiques of formalisms. No one today wants to revive the evolutionary scheme Frazer proposed, but scholars are just as leery of the reductive (universal) psychologizing explanations proposed by logicians who see everything as metaphor. The stakes, as our world is engulfed by manifold crises, are too high to indulge in such games.

By Magdalena Korzeniewska, aka Bubug. You can see more of her images here.

In fact, one of the animal forms a Feldgeist might take is a dog: der Kornhund (corn-dog). However, German Corn Dogs (in the sense of spirits, not sausages fried in batter) seem to be less prevalent than Corn Wolves.

In Scotland and Ireland, the first farmer to finish the grain harvest made a corn dolly that was called the Cailleach (or the Carline) from the last sheaf of his crop. He could then pass it to another farmer, and when he, in turn, had finished harvesting, he would pass it to another, and so on until it reached the last one to finish clearing his fields. This one would then have to keep the “hag” through the winter.

See Palmié, p. 30.

Some of my readers are very familiar with concepts like metaphysics, while others are not. For the sake of the latter group, let’s break it down a little: metaphysics is a branch of philosophy that explains inherent or universal elements of reality which cannot be experienced through our senses or, generally, experienced in everyday life by those living outside of a given metaphysical model. (Example: a farmer prays to Ceres for his crops, and the crops thrive. However, he may not succeed in convincing another farmer who doesn’t believe in Ceres that she was the reason for his bountiful harvest. The other farmer may believe it was due to some other factor.)

In folk usage, we see “metaphysical” used in contexts such as “metaphysical shops” where goods such as crystals, tarot decks, or deity icons are sold. In such cases, it has become a shorthand for “pagan,” “occult,” “New Age,” or … well, you get the point. The underlying reason for the name is that metaphysics cannot do without images of one kind or another.

In formal philosophy, metaphysics traditionally posited first causes or deities as an underlying reality, as in our example with Ceres, or any philosophy based on the god of the Bible, or, indeed any cosmologies, but the more modern practice of metaphysics provides vocabulary and systems of logic that can be used to formally analyze beliefs rather than simply asserting them. Some areas of interest to metaphysicians are the definition and meaning of existence, considerations about reality, the nature of the human mind, and the nature of space, time, and/or causality.

And this was part of why Wittgenstein found Karl Popper so vexing — Popper had failed to understand his arguments, and went ahead and constructed his own philosophy around his misunderstandings. Wittgenstein’s position had shifted from the claim he made in the Tractatus that there are metaphysical truths which are ineffable to the view that such “truths” are either nonsense or mere norms of descriptions. In the infamous 1946 poker incident, Wittgenstein challenged Popper to provide an example of a universally valid moral rule and Popper replied “Thou shalt not threaten a visiting lecturer with a poker.” Or, in other words, “eff* this — there really are valid and binding rules!”

(*Sorry/not sorry!)

Quoted from p. 64 in Palmié.

Sometimes, Frazer reports, a woman had to actually become the Wolf herself:

The last sheaf of corn is also called the Wolf or the Rye-wolf or the Oats-wolf according to the crop, and of the woman who binds it they say, “The Wolf is biting her,” “She has the Wolf,” “She must fetch the Wolf” (out of the corn). Moreover, she herself is called Wolf; they cry out to her, “Thou art the Wolf,” and she has to bear the name for a whole year; sometimes, according to the crop, she is called the Rye-wolf or the Potato-wolf. In the island of Rügen not only is the woman who binds the last sheaf called Wolf, but when she comes home she bites the lady of the house and the stewardess, for which she receives a large piece of meat. Yet nobody likes to be the Wolf.

This essay by Yoav Rinon discusses Derrida’s Plato’s Pharmacy. In Plato’s account of Socrates’ retelling of the Egyptian myth of a god called Theuth, a king who has an audience with this deity is told that writing is going to be a new “φάρμακον (pharmakon) of wisdom and truth.” However, translations of the Greek term into other languages erase its ambiguity and prevent all the possible interpretations and lines of inquiry. And this is the key point, because writing, in Socrates’/Plato’s retelling of this myth, becomes a new means of obscuring truth and of producing the mere illusions of memory and wisdom.

For more about the folk tales collected by Schönwerth, see my article “Ring of Bones,” which was very recently published by A Beautiful Resistance.

So, here we have found out that the Lady of the Woods is an unmarried goddess who is concerned with the domestic arts. It would be intriguing to know whether the Lady of the Woods is a distant echo of the moirae, the norns, or perhaps even Athena.

I’m citing from material that was lent to me by Robin Artisson, whose course “Upon the Rood-Day: The Witchcraft of Christsonday and the Queen of Elphen" discusses the figure of Christsonday and the context for belief in this spirit in a wealth of detail. He pored over all the information known to contemporary scholars that relates to his lore, and examined accounts taken from two early modern Witches, Andro Man and Marion Grant. Click here for more information about the course. Registration is currently closed, but should reopen soon. I’ve heard it’s very a very enriching experience and I would like to join it when I can.

Most people agree that highly-processed foods are unhealthy, but let’s not make scapegoats out of those who must rely on them. Critics increasingly say that "junk food" is a term that has outlived its usefulness because it reflects cultural capital rather than objective standards for healthfulness. Stigmatizing those on low budgets or those who have not benefited from better-developed food cultures is cruel and useless snobbery. On the other hand, failing to address the systemic problems of agribusiness, logistics, and nutritional education only allows them to accelerate, and virtual-signalling one’s sensitivity to others’ plight does nothing to change the diets that are making them sick and miserable. Recently, hyper-processed foods overtook tobacco as the leading cause of early death worldwide, which is a fact that calls for complex approaches and not just positive spin from those who are in a position to engage in activism or exert leverage somewhere.

I applied for a fellowship from the (American) National Endowment for the Humanities to support me while I work on the more intense stages of research and writing, but will not find out whether my application is successful until mid-December of this year. (Please keep your fingers crossed!)

Dale Pendell, The Language of Birds, p. 10.

The most egregious example of academic agribusiness writing is produced under the name of José Manuel Lorenzo. This researcher put his name on 176 papers last year, and — according to industry statistics — he publishes a study every other day (if you include weekends)

Where does he find the time to do all this research and writing? one wonders.

India is one of the countries where so-called “paper mills” are concentrated — factories that churn out scientific studies which are already written and ready to be published in specialized journals. Co-authorship is offered in exchange for money. EL PAÍS requested price rates from one of the Indian companies that sends their offers to Spanish scientists: iTrilon, based in Chennai. The company’s scientific director Sarath Ranganathan offered the possibility of being the first author of a study that was already written — entitled Next-generation neurotherapies against Alzheimer’s — in exchange for about $500. It’s also possible to be the fifth co-author of an article titled Emergence of rare microbial infections in India for $430. iTrilon promises to publish these ready-made studies in the journals of the world’s leading scientific publishers: Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, Springer Nature, Science and Wiley. Last year, the academic publishing industry acknowledged that at least 2% of studies each journal receives are considered to be suspicious. Sometimes, the number of suspicious studies is marked as high as 46%.

Lorenzo categorically denies having resorted to these services, but he is aware of the existence of a market for the sale of authorship. “I received several emails from a person who offered to pay me €1,000 or €2,000 [$1,070-$2,144] to put him as a co-author, but I didn’t even answer,” he affirms. Lorenzo says that scientists from India, Pakistan, Iraq and other countries often invite him to collaborate, even if they don’t know him. According to him, plant biochemist Manoj Kumar — from the Central Institute for Research on Cotton Technology, in Bombay — asked him to participate in a study on the treatment of gum diseases and he — an expert in meat — accepted. Lorenzo says that he limited himself to reviewing the English, proposing some graphics and signing it as co-author ...

... Scientific journals have a perverse incentive to publish studies of dubious quality. In the past, it was readers who paid to read the articles, which were inaccessible without a subscription. But in recent years, another model has been imposed, in which the authors themselves are the ones who pay up to $6,500 to private publishers so that their studies can be published with open access to any reader. The change in this model has caused an earthquake in the world of science. In 2015, there were barely a dozen biomedical journals that each published more than 2,000 studies per year, representing 6% of total production between them. There are now 55 of these so-called “mega-journals” — together, they publish almost a quarter of all specialized literature, according to recent research by John Ioannidis.

Half of the top mega-journals come from the same publisher ...

Read more about the changes in academic publishing here — and keep in mind that this was already happening before the advent of AI text generation.

Quoting from Taussig again, ”Agribusiness writing wants to drain the wetlands. Swamps, they used to be called, dank places where bugs multiply. As if by magic, the disorder of the world will be straightened out. Rarely if ever with such writing do we get the sense of chaos moving not to order but to another form of chaos as with Nietzsche’s dancing stars with chaos in their hearts.”

That might seem to recall Wittgenstein’s Remark No. 17 on Frazer: “We must plough over language in its entirety,” but despite his bluster, it seems to me that the philosopher didn’t believe such a thing was truly possible because he kept coming back to an irrational common core which he posited made all humans alike, whether they were engaging in “primitive” rituals or kissing a photograph of a loved one. Neurotic compulsion is an even flatter explanation than metaphysics being a form of magic.