Balance, by Ruth Evans.

First, a clarification:

A discussion arose about the origin of the phrase “loose woman” eight years ago at the English Stack Exchange when the OP wrote in to ask whether it refers explicitly to vaginas.

It doesn’t — that’s not how that works, despite propaganda from liars who promote purity culture and who believe they can read character through physiognomy — the pseudoscience of divination through a person's form or features.

(Yes, Mr. Omokri stuck … something … into these greyish, rotten-looking pieces of salmon in order to mansplain vaginas — to women. We’re all familiar with the hypocritical and misogynist claim that a woman’s “body count” inversely correlates with her honor and value as a human being. However, in addition to Omokri’s lack of understanding of female anatomy, his idea wouldn’t hold up even if what he claimed was true. His theory fails because the supposed effect of one penis 4x and of four different ones one time each would have to be the same. And I can’t help wondering if he ate this salmon afterwards.)

Maybe he’s never seen a woman naked, but even women sometimes post similar crap: here’s one who doesn’t know the difference between the vagina and a vulva, and likes to talk about her child’s genitalia online:

Sorry about that! Here, refresh your eyes at this blessed healing fountain:

And let’s clear the air with a round of saging:

Ah, much better! Now we’ll put all that tasteless nonsense aside.

Loosing the bonds

So, back to the discussion I mentioned at the very beginning of the article: knowledgeable contributors to the Stack Exchange suggested etymologies and identified instances of use attested in the Early English Books Online (EBBO) database. Interestingly, one of the gleanings from the discussion is that the concept of a “loose” (unchaste, immoral) woman predates “loose morals,” so it would seem that the specific case of female immorality was later extended to more kinds of cases. There is the sense of having undone the “ties that bind” one in marriage, so this is what the loose woman has unbound herself from, if she was ever bound in the first place. The loose woman is an adulteress, a prostitute, a courtesan, an unmarried seductress … or — let’s be honest here — maybe a rape victim. Cultures that treat wives and daughters as chattel and those which practice patrilineal inheritance do not want women acting on their own sexual urges, and in order to be really, really demotivate it, they also punish those who were forced into sexual acts, because — among other reasons — it takes the way the opportunity of using non-consent as an alibi.

For the sake of balance, of course “too much” sexual looseness can also sometimes be the result of unhealthy boundaries. In cases of compulsion, addiction, or extreme forms of people-pleasing it can lead to a sense of losing oneself, as the psychotherapist Kerry Cohen, who specializes in love and sex addiction, has written about in her memoir titled Loose Girl. However, Cohen is no prude: moderation, and the sense that one’s behavior is in harmony with one’s needs and the needs of partners, the knowledge that one’s sexual behavior supports integrity in other areas of life are key. How much or how little sexual behavior (and what kinds) are in a healthy, fun, and honest range will vary greatly from one person to another.

Incontinence

The meaning we usually associate with this word today (inability to control discharges from the bowels or bladder) dates to the 19th century. However, in earlier texts, incontinence referred to giving free rein to carnal desires. The incontinent individual knows better, but finds themself unable to master their appetites. If you look all the way back, incontinence derives from the PIE root *ten-, which refers to stretching. It sounds “loose,” right? But by contrast with the superstitions about “loose women” described at the beginning of this essay, the original meaning of an incontinent person is one who fails to hold in desires that arise from within themself. This is opposed to one who cannot resist overwhelming temptation from an external source.

The idea of incontinence as a negative character trait was discussed by Aristotle 2300 years ago in the Nicomachean Ethics, a treatise largely devoted to how to create a life of eudaemonia, or full human flourishing. Aristotle bases his ethical theory in psychology and the realities of human nature, and he asserts that there are no known absolute moral standards. Virtuous acts can only occur in a social context and not an abstract one, and the goal is a balance that finds a sweet spot between excess and deficiency.

Aristotle’s work had a profound influence on European thinking in the Middle Ages, as it was adopted and synthesized with Christian texts. The Western Scholastic tradition in philosophy was developed out of this fusion. The painting below does not illustrate the principle of balance; rather it is of one between goodness and wickedness, symbolized — of course — by two women.

Paolo Veronese, Young Man Between Vice and Virtue, ca. 1560. Here, we see Vice looking like a blonde Venetian courtesan with very loose garments, in the form of a blond Venetian courtesan with a generous décolleté and jeweled adornments calling out to the youth. This scene is based on the fictitious story by Prodicus told by the Greek historian and philosopher Xenophon (430-354 BCE) in his Memorabilia. The same story, told as Hercules being solicited by both paths, was also mentioned by Saint Basil, and Veronese painted this scene as well. As in this image, the female personification of Vice had clothing that was coming unfastened and she had a bare-breasted sphinx behind her. It is interesting to note that in the Renaissance and Baroque eras many female allegorical figures might be depicted bare-breasted (e.g. Victory, Peace, Flora), but if a contrast was presented, it was always in favor of the well-covered figure.

Could there be a third path? That’s something I’ll be talking about in a forthcoming article on Thomas the Rhymer and Third Path Writing.

Be sure you don’t miss it!

Back to the Nicomachean Ethics: in Book VII, Impediments to Virtue, Chapter 8 is titled "Incontinence compared with vice and virtue”. Here’s what Aristotle had to say on the subject:

We have seen that incontinence is not vice, but perhaps we may say that it is in a manner vice. The difference is that the vicious man acts with deliberate purpose, while the incontinent man acts against it. But in spite of this difference their acts are similar; as Demodocus said against the Milesians, “The Milesians are not fools, but they act like fools.” So an incontinent man is not unjust, but will act unjustly.

It is the character of the incontinent man to pursue, without being convinced of their goodness, bodily pleasures that exceed the bounds of moderation and are contrary to right reason; but the profligate man is convinced that these things are good because it is his character to pursue them: the former, then, may be easily brought to a better mind, the latter not. For virtue preserves, but vice destroys the principle; but in matters of conduct the motive [end or final cause] is the principle [beginning or efficient cause] of action, holding the same place here that the hypotheses do in mathematics. In mathematics no reasoning or demonstration can instruct us about these principles or starting points; so here it is not reason but virtue, either natural or acquired by training, that teaches us to hold right opinions about the principle of action. A man of this character, then, is temperate, while a man of opposite character is profligate.

But there is a class of people who are apt to be momentarily deprived of their right senses by passion, and who are swayed by passion so far as not to act according to reason, but not so far that it has become part of their nature to believe that they ought to pursue pleasures of this kind without limit. These are the incontinent, who are better than the profligate, and not absolutely bad; for the best part of our nature, the principle of right conduct, still survives in them.

To these are opposed another class of people who are wont to abide by their resolutions, and not to be deprived of their senses by passion at least. It is plain from this, then, that the latter is a good type of character, the former not good.

Thus, we see that incontinence, classically conceived, is not so much any particular act as any form of behavior that errs against the virtue of temperance. It is temporary, unless it becomes recurrent (similar to “he’s not really like that, he’s just being that way” — the truth of the statement depends on context and frequency. The remedy for this deviation from one’s resolutions, according to Aristotle, was to practice good habits, which would become self-reinforcing.

The classic representation of Temperance is a female or gender-ambiguous figure with or without wings1 pouring liquid from one vessel into another. The iconic figure may refer to the ancient habit of mixing water with wine, or it may be the “water of life.” And the meaning of the card is balance, moderation, peace, health, hygiene, and patience. This card was created by M. at Dark Tarot, and if you like their artwork you can print a free deck for personal use.

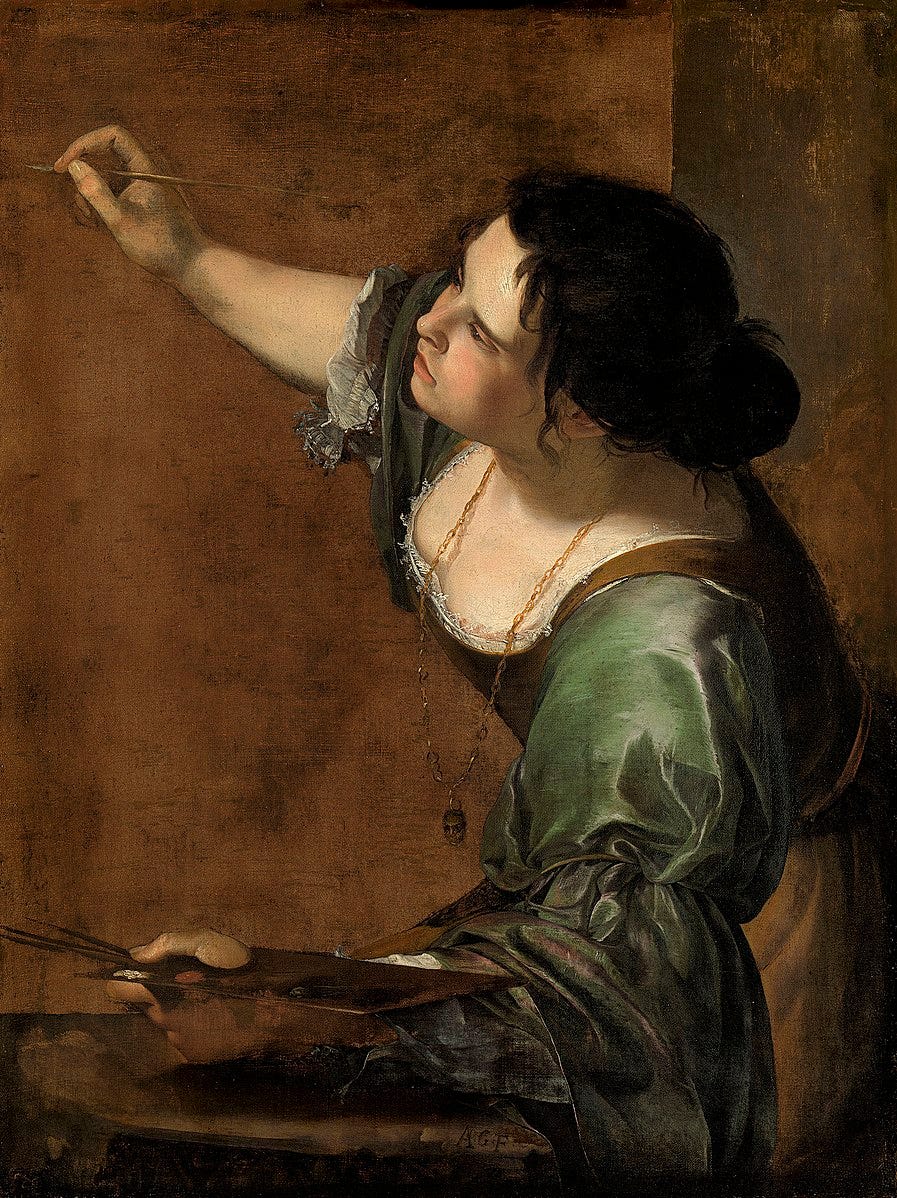

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory of Inclination

Notice the similarity between Temperance and Artemisia Gentileschi’s Allegory of Inclination:

Gentileschi’s allegorical figure, however, is not holding a vessel filled with water — the bowl-like object is actually a mariner's compass. This, in my opinion, shows an affinity with the theme of The Star, which signifies inspiration, optimism, joy, blessings (of the stars) and contentment. Note that, like Temperance, the figure in The Star is also dealing with flowing waters — and Gentileschi’s painting has a star behind the figure.

The Dark Tarot card I embedded above does not show a lush, flowering landscape for Temperance, but the Rider-Waite-Smith deck has it in both cards. I think it’s a key detail!

Here is the Rider-Waite-Smith Temperance:

Temperance also features blooming calamus (Acorus calamus, the yellow iris), which herbalists use to improve mental focus, clear away “cobwebs” and mind fog, and integrate various types of perception into holistic understanding.

Astrid Bridgwood tells us that Gentileschi’s Allegory of Inclination was completed during the artist’s study as she lived and worked in Florence, Italy. During this period, she solidified her status as an artist who worked independently of her father’s supervision. This work was commissioned around 1618 by Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger, a Florentine poet and relative of the famous sculptor, painter, and poet, as part of a series that were to exalt the Renaissance artist’s genius. “Inclination” in the title refers to innate talent, genius, or artistic disposition, and the figure used to represent “Inclination” bears a significant resemblance to Gentileschi herself.

To hell with the “male gaze” — this woman is unconcerned with whoever is looking at her. She looks away and her attention seems to be focused on receiving a download from the star above her head. Her eyes, and her compass point are also oriented toward the star.

Artemesia Gentileschi’s fuckin’ badass Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (1638-39). Note her skull pendant. Source: Wikipedia.

Artemesia Gentileschi was best known for painting very fierce women, and — make no mistake — this is one of them. In Allegory of Inclination, she seems to be confirming through practice (reading the compass) what the signs in the heavens already told her, showing a harmony of inspiration and action, devoid of hypocrisy and pretense (as shown by her nudity), all of which directly challenged many ideas in her society.

Try to image what then happened: sometime around 1684 Leonardo da Buonarroto (Michaelangelo’s great nephew) hired Baldassarre Franceschini to paint blue drapery and veils over the inspired woman’s breasts and navel “to preserve the modesty of the female inhabitants of the house.” Perhaps he believed these women, like that Christian lady with her accursed ham sandwiches, would be ignorant of female anatomy if they didn’t see it in paintings. Certainly, he was hoping they wouldn’t take an example from her “shamelessness” in her nudity, or, probably, her unladylike openness to science and to artistic inspiration.

338 years later, in 2022, art historians virtually (i.e., digitally, not physically) removed the drapery2 as part of the Artemisia UpClose project:

Venus Cloacina and the Cloaca Maxima: Cleansing Waters, Fighting Demons

Venus Cloacina, a goddess who supervised the Romans’ main drain, makes an excellent example of this idea of flowing, cleansing waters and healthful balance that we saw in the Temperance and Star tarot cards. Cloacina's name comes from the Latin verb cloare or cluere, meaning "to wash, clean or purify," and over time the word became associated with sewers and with the multifunction rear orifice of some creatures.

Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, the author of The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy, points out that there were a few key differences between Roman sensibilities and ours in the area of hygiene, and that Etruscan and Roman sewer systems were more about drainage of standing water than the removal of filth and effluvia, and that Romans' “sense of cleanliness and privacy around bathroom matters was quite different from our tender modern sensibilities.”

And the system had its vulnerabilities: they needed Cloacina and other holy guardians (including Fortuna, who was sometimes painted on the walls of public latrines) to ensure that sewer demons did not creep up through the plumbing and wreak havoc in the city. This may sound fanciful, but there actually was some basis to their fear. Sometimes, flames caused by explosions of hydrogen sulphide and methane exploded from the seat openings latrines. There were also rats and other small vermin — and more supernatural threats.

One late Roman writer tells a particularly exciting story about such a demon. A certain Dexianos was sitting on the privy in the middle of the night, the text tells us, when a demon raised itself in front of him with savage ferocity. As soon as Dexianos saw the “hellish and insane” demon, he “became stunned, seized with fear and trembling, and covered with sweat.” Source.

Was he crazy? I bet he wasn’t. Any of the difficulties I named above could terrify a person sitting on the loo late at night. But there’s more: Aelian (Claudius Aelianus), writes in On the Nature of Animals about an octopus that was wont to swim up through a subterranean sewer that discharged into the ocean. And one can easily imagine the horror some visitors to the public latrines must have felt if they got their bottoms wiped or fondled by a waving tentacle.3

Thalia Took reminds us that although a sewer goddess “sounds terribly unromantic; remember thought that the Romans were a very practical people, and that the complex sewer and drainage system that Rome developed kept the city clean, funnelling refuse and rainwater out and away, as well as draining the potentially malaria-infested swamps of the Forum, all of which helped to keep the populace healthy.”

A Roman denarius with Venus Cloacina. A similar nimbus can also be seen on some statues of Hekate (Hekate Chiaramonte) and on the American Statue of Liberty, which is perhaps significant, and perhaps not, so let’s leave it aside.

Cloacina was originally an Etruscan goddess or nymph (naiad) of the stream that ran through the Roman Forum, but she became assimilated with Venus either after peace was made with the Sabines, in a later stage of the construction of municipal waterworks, or upon determination that this sphere of influence did, indeed, belong to Venus. Naturally, the whole complex of ideas also involved prescriptions for women’s sexuality (though men’s sexuality seems to be neglected). Here is an excellent summary from the blog Honor the Gods:

The Etruscans were excellent engineers who developed hydrotechnology to provide wells, cisterns, irrigation, drainage and sewers. These underground tunnels were called cuniculi (singular: cuninculus), from the Ancient Greek κόνικλος (kóniklos) meaning “burrow”. And if you’re thinking that sounds like the word “cunt,” you’re right …

The Etruscans placed these highly important waterways under the protection of the goddess Cloacina. The goddess’ name seems to come from the root cluere, which originally meant “running water” or “stream” and came to mean “to cleanse or purify.”

… Like the Etruscans, the Romans were conscious of the importance of this infrastructure. They named it the Cloaca Maxima, the “great purifying stream,” and placed it under the protection of a goddess they called Venus Cloacina …

Religious syncetism, the blending of two ideas or deities, frequently occurred in ancient religions. In this case, the Romans associated the purview of the Etruscan goddess Cloacina (running water, purification) with the areas under the influence of Venus (sex and fertility – in which the vulva, or cunt, plays an important role … ) Thus Venus, with the addition of the epithet “Cloacina,” became a goddess of purification, and not just purification of the city from sewage, but also purifcation of the body from filth, and purification of the mind and soul from inappropriate desires.

The purificatory aspect of Venus can also be seen in the Roman festival of Veneralia, which was established at the direction of the Sibylline Oracle in response to incidents of sexual impropriety by women in Rome. During the Veneralia, Venus was honored under the epithet Verticordia, “the changer of hearts”, an aspect of the goddess which encouraged Roman women to practice sexual conduct appropriate to their married or unmarried state. During the Venerealia, the cult statue of Venus Verticordia (now lost) was removed from her temple in Rome and taken to the baths. There, female attendants removed the goddess’ garments and personal ornaments to bathe and perfume her, and dress her in fresh garments and readorn her with jewelry. The statue was then arrayed with a festive crown and garlands of myrtle and roses, and returned to her temple for public rites. Those interested in love and marriage offered private prayers to Venus during the Veneralia in hopes of receiving those blessings.

The Roman Cloaca Maxima today. Damn, they were good engineers!

Don’t judge: obsession with ancient Romans isn’t just a guy thing!

Well, what kind of temptation is it? And where does it come from?

The question of whether our thoughts and desires arise from within us or from external stimuli has kept philosophers (and many others) occupied for ages. Did Descartes have the right of it when he isolated human consciousness and our distinct mode of being in the act of self-aware cognition? Is the cogito irreducible? I don’t think so — even if one is unwilling to entertain animist notions of interbeing,4 it is undeniable that we exist in and through human cultures and interactions. Hume may have been onto something with his argument that all knowledge and ideas arise from impressions (sensations).

If Hume is right, as my philosopher friend Levi Paul Bryant explains in his lectures, it would be “devastating to Descartes’s argument for the existence of God … because it shows that ideas originate from experience and therefore doesn’t permit inference to God’s existence from the idea alone.” Gods, spirits, ghosts, deities may as well not exist if you have no experience of them. He makes his point by drawing on Freud’s “more humean” theories of infant development

centered in developmental delay, the utter helplessness of the infant, the chaos of the body, and experience of the caregivers. This allows for a discussion of how the objects of need get bound up with relations to these key others turning things into signs of love, the role of parental presence and absence of the caregivers in early moral development, the impact of different disciplinary parenting styles on later adulthood moral universes, why it can be so traumatic for a young child to witness a parent lain low undermining their sense of ontological security, and why people often yearn for God later in life when they are in situations of helplessness. I really love this lecture because it gets them thinking about and reflecting on why they might think as they do. I think there’s something powerful in our own thought becoming strange and mysterious to us [emphasis mine].

Here’s the takeaway for our purposes here:

The next time you feel a new or unexpected desire, ask yourself: where is it coming from? Is it emerging from within you and seeking an object to satisfy it, or do you feel that an object is affecting you and changing your previous intentions? Are you inspired like the figure underneath The Star, or are you called, like Temperance, to rebalance the vital force and keep it flowing? If your morals or commitments are challenged, would it be wise to loosen up self-restrictions or take a break from habitual restraint (becoming less “continent” in the old sense), or would that lead to folly and unacceptable consequences? (Fucking around / finding out) Or even to the beginning of a habit which will eventually become part of your character?

Or — is there something much broader than your girdle that might be loosened?

Reclaiming “looseness”

This print, titled Diana, is my favorite of all of Dave Seed's fine art illustrations. As you can read in one of my other articles, it was based on a Christian rendering of a “loose woman” in a church.5

It is certainly not accidental that the idea of a woman with loose sexual morals is associated with one who is sinning against the god of the Bible. The Hebrew verb zânâh [זָנָה] appears 93 times in the Old Testament. Usually it is rendered as “committing adultery” or “playing the harlot,” and it almost always refers to female sexual actions rather than male ones (less commonly, it may be used to describe a victim of rape). Interestingly, the verb seems to derive from a primitive root that means “highly fed, and therefore wanton,” which brings us back to the discussion of the original sense of “incontenence” above. However, zânâh was also used idiomatically for spiritual "backsliding" (i.e. worshiping their Caananite neighbors’ gods). While the authors of Biblical texts — and religious authorities who interpret them today — seem pretty sure that “temple prostitution” was a thing, the evidence for it is actually pretty thin, and it’s likely they were just engaged in negative PR against rival cults.

Another way to think about loose women

"Loose" women in the sense of seductresses with spoiled bodies are a construct of patriarchy and systems of social orders I think most of my readers have little sympathy for, but I think the concept is ripe for reclaiming …

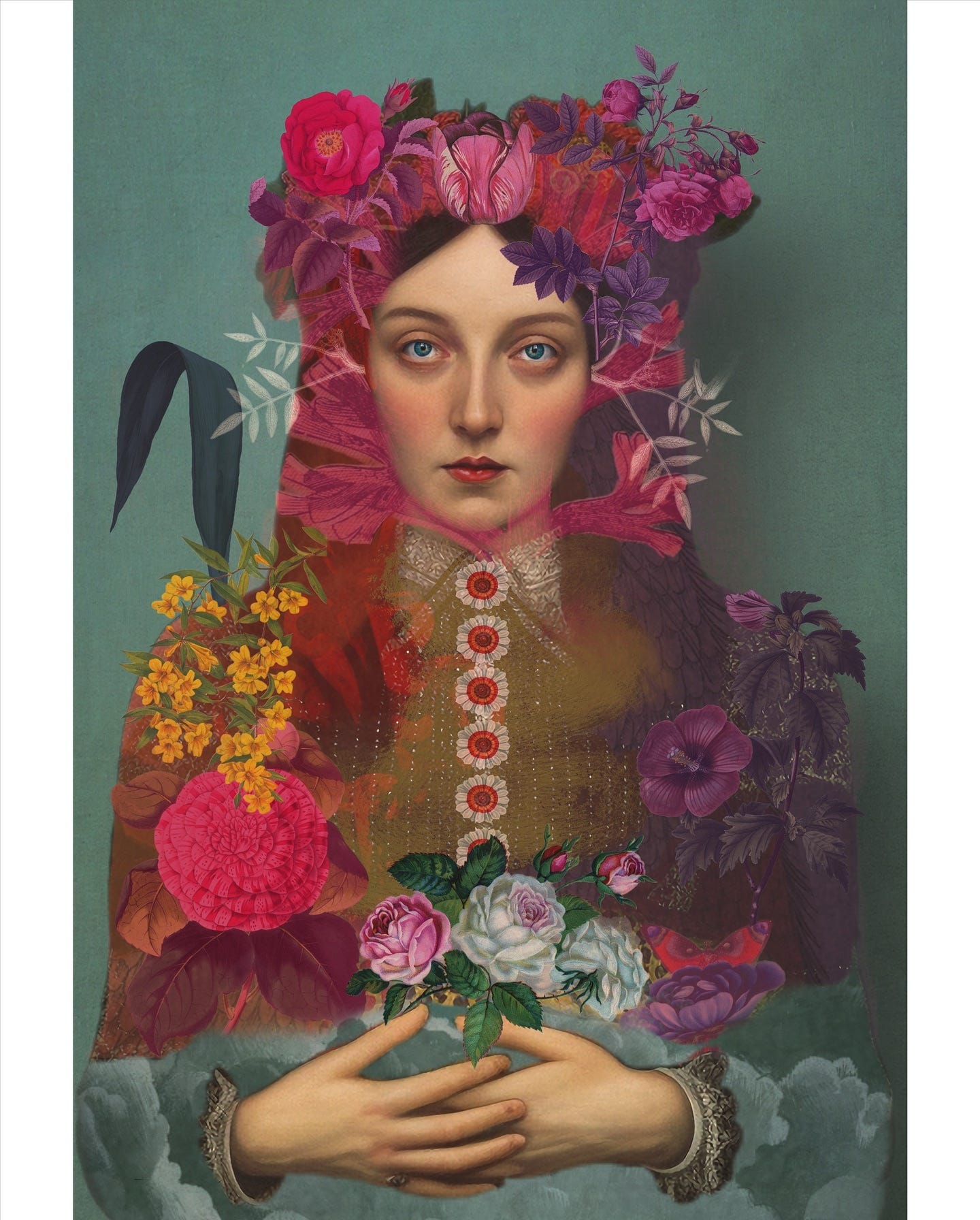

Woman of the Wild, by SheWhoIsArt on Etsy.

So let’s think about it a little differently. We’ll refrain from telling consenting adults what to do with their bodies, only reminding them that integrity (or its lack) will have profound effects on the quality of their lives.

When I speak now of “loose women,” I do not mean to refer only to those of female sex and feminine gender. My ideas apply to everyone, but I am retaining the feminine terms as a response to millennia to patriarchal imposition. (As we saw in the illustrations of fish and sandwiches at the top of the post.) If the words speak to you, they were written for you, no matter how you identify.

Enlightenment II, by Sarah Jarrett

What if a "loose" woman was porous? Open to her ecosystem. To shifts in season and weather. To sondering an animal, a tree, a lake? Nature would come alive for her in ways unimaginable to those who see it as mere matter obedient only to chemical and biological laws and, at most, to insensible instincts. She could then become a sage, an oracle, and possibly the voice of a more sensible order.

Sonder,6 by collage artist Sarah Jarrett.

OK, so you haven’t seen all the memes: what does “sonder” mean? It’s a neologism coined by John Koenig that was collected in his Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. This is how Koenig defines it:

n. the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own—populated with their own ambitions, friends, routines, worries and inherited craziness—an epic story that continues invisibly around you like an anthill sprawling deep underground, with elaborate passageways to thousands of other lives that you’ll never know existed, in which you might appear only once, as an extra sipping coffee in the background, as a blur of traffic passing on the highway, as a lighted window at dusk.

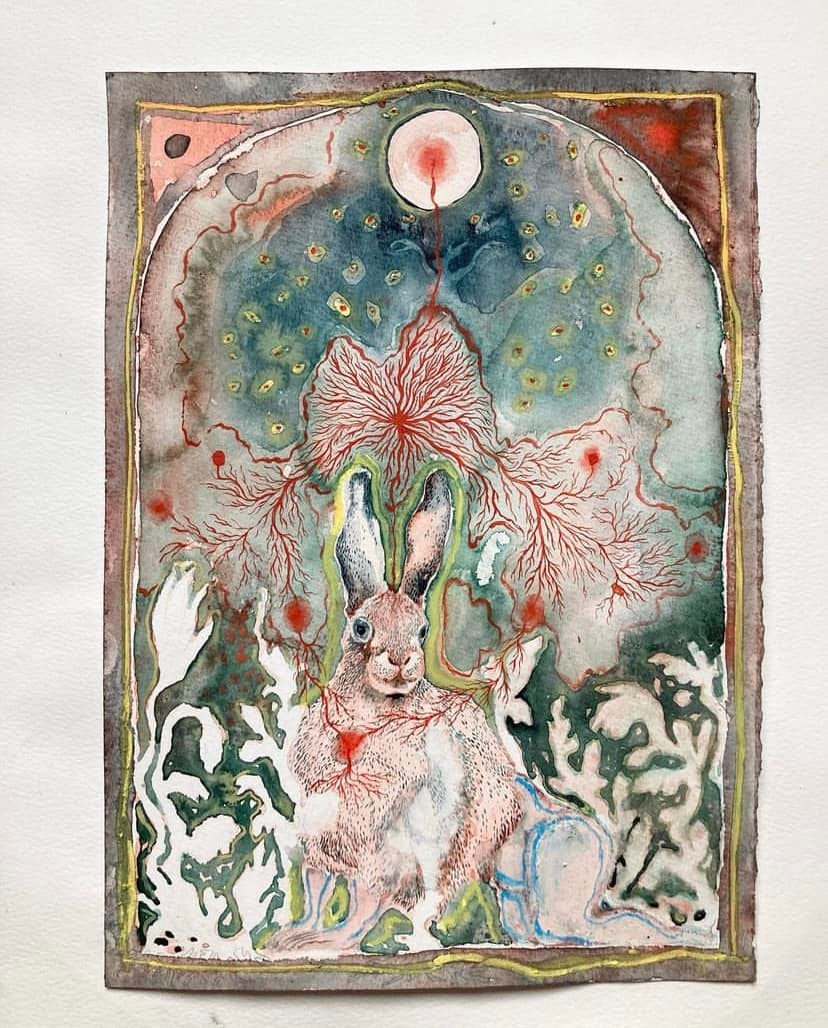

If one is open to sondering other people, there’s no reason why the practice cannot be further extended. Certainly, this is what many shamans do, and, as testified by a wide variety of historical sources, what many witches in the Early Modern period believed they were doing when they transformed into animals.

And I Shall Go Into A Hare,7 watercolor by Nooka Shepherd. I can’t possibly love this young artist’s work enough!

The reasons why people might deliberately move their consciousness in a trance or dream state into another being vary greatly. However, when a woman has become loose enough to move her consciousness and self-feeling into the body of another, whether it be animal, a mythbeing such as the guardian of a stream or a spirit of a place, she becomes receptive to messages that are obscured from those who are only looking and seeing in ordinary ways. It is usually not the highest and proudest members of a society who seek out such experiences: it tends to be the humble, those underneath the well-heeled: the witch, the washerwoman, the gardener. Or the highborn woman who has been set aside by her family, consigned to life as a sibyl or tender of the sacred flame.

If this woman then shares what she has learned, perhaps as an explicit message (as well maidens and oracles of old used to do), or if she is free enough to act as a living example of one who has unshackled herself from restrictive authority, she has the potential to transform and reawaken many of those around her. If she acts on behalf of the interconnected web of life around her rather than out of hopes and fears instilled by authority figures and their self-serving dogmas, she will open up long-dried wells so they can sing again, and the wise will listen and learn from her example.8

Photograph by Russian artist Natalia Drepina.

p.s. A new batch of posts will soon follow this one — I’ve been working on several simultaneously. If this discussion of waterways and women interested you, be sure to catch the article about nymphs, naiads (water nymphs), and prophetic well maidens, two deep explorations into the history and origins of Medusa, and a presentation of my nonfiction writing method.

Why nonbinary human figures with wings? My guess is that the Byzantine idea of angels as intermediary figures between humans and God, which they conflated with the role of eunuchs, who were also considered intermediary figures who socially functioned as nonbinary individuals who more angelic than ordinary men or women has influenced the iconography. At its heart, Temperance represents the balance between all extremes and thus also binaries.

This is some stone-cold badassery by the conservationists!

While I usually don’t talk about my personal life on this blog, I do want to share something in these footnotes: I hope to join an Associate’s Degree program in antique restoration in September ‘24. It’s offered at a high school and college in Turnov, northeast Bohemia, and since it’s an adult-ed program it will take four years to complete my studies there.

What will I do with the knowledge of how to restore art and artifacts? Pull veils off painted figures? Removed curses from haunted objects? Put curses onto objects and make them haunted? Or just bring some beauty back into our world as an act of resistance against the indifference and hostility of earlier ages?

Or — maybe I’ll finally apply for a position in the infamous Williams College Art Mafia!

Octopuses naturally, with the lapse of time, attain to enormous proportions and approach cetaceans and are actually reckoned as such. At any rate I learn of an octopus at Dicaearchia in Italy which attained to a monstrous bulk and scorned and despised food from the sea and such pasturage as it provided. And so this creature actually came out on to the land and seized things there. Now it swam up through a subterranean sewer that discharged the refuse of the aforesaid city into the sea and emerged in a house on the shore where some Iberian merchants had their cargo, that is, pickled fish from that country in immense jars: it threw its tentacles round the earthenware vessels and with its grip broke them and feasted on the pickled fish. And when the merchants entered and saw the broken pieces, they realised that a large quantity of their cargo had disappeared ; and they were amazed and could not guess who had robbed them: they saw that no attempt had been made upon the doors; the roof was undamaged; the walls had not been broken through. They saw also the remains of the pickled fish that had been left behind by the uninvited guest. So they decided to have their most courageous servant armed and waiting in ambush in the house. Well, during the night the octopus crept up to its accustomed meal and clasping the vessels, as an athlete puts a strangle-hold upon his adversary with all his might gripping firmly, the robber - if I may so call the octopus - crushed the earthenware with the greatest ease. It was full moon, and the house was full of light, and everything was quite visible. But the servant was not for attacking the brute single-handed as he was afraid, moreover his adversary was too big for one man, but in the morning he informed the merchants what had happened. They could not believe their ears. Then some of them remembering how much they had lost, were for risking the danger and were eager to encounter their enemy, while others in their thirst for this singular and incredible spectacle voluntarily shut themselves up with their companions in order to help them. Later, in the evening the marauder paid his visit and made for his usual feast. Thereupon some of them closed off the conduit; others took arms against the enemy and with choppers and razors well sharpened cut the tentacles, just as vine-dressers and woodmen lop the tips of the branches of an oak. And having cut away its strength, at long last they overcame it not without considerable labour. And what was so strange was that merchants captured the fish on dry land. Mischief and craft are plainly seen to be characteristics of this creature.

Animist notions of interbeing are what I adore and most passionately advocate for. Previously denigrated as the left-behind superstitions of the world’s most “primitive” and “savage” people and of our distant ancestors in the contemporary Western context, now they often associated with Paganism and witchcraft. As Christianity’s high tide continues to ebb in Europe and North America, these movements are only slowly entering into academic discourse and some semblance of “respectability.”

But the real goal was always something much more wonderful than getting into those lunch clubs!

Per Peter Grey’s Apocalyptic Witchcraft, which is — in my view — an essential manifesto on neoamimism,

Witchcraft is part of a living web of species and relationships, a world which we have forgotten to observe, understand or inhabit. Many people reading this paragraph will not know even the current phase of the moon, and if asked for it will not instinctively look up to the current quarter of the sky, but down to their computers.

Neither will they be able to name the plants, birds or animals within a metre or mile radius of their door. Witchcraft asks that we do these first things, this is presence.

Animism is not embedded in the natural world, it is the natural world.

Our witchcraft is that spirit of place, which is made from a convergence of elements and inhabitants. Here I include animals, both living and dead, human and inhuman. Our helpers are mammals, reptiles, fish, birds and insects. Some can be counted allies, others are more ambivalent. Predator and prey are interdependent. These all have the same origin and ancestry, they form from plants, from copper green life. Bones become soil. The plants have been nourished on the minerals drawn up from the bowels of the earth.

These are the living tools of the witch's craft. The cycle of the elements and seasons is read in this way. Flux, life and death are part of this, as are extinctions, catastrophe, fire and flood. We avail ourselves of these, and ultimately a balance is sought. Our ritual space is written in starlight, watched over by sun and moon.

David wrote:

I was inspired by one of the carved misericords at the Holy Trinity Church in Stratford upon Avon. The original carving is described as being of a "loose woman rejecting Christianity," the stag apparently symbolising Christ, and her right hand "blocking a flowering rose symbolising the Virgin Mary". If you look at the carving I'd argue that that is a load of old toot. She's actually holding the rose and the stag seems an unlikely symbol for Christ. A lamb would be more the thing. I like to think it might be more about the carvers employing images drawn from older traditions. Diana is sometimes depicted riding a stag. Anyway, my drawing isn't about the dangers of loose women. I'm not entirely sure WHAT it's about. If I was good at describing this stuff I wouldn't have to draw it.

The concept of sondering has become widely popular and has been adopted in the names of numerous cafes around the world, which is a nice suggestion to patrons that they truly listen and try to understand one another.

The title was taken from the confessions recorded from accused witch Isobel Gowdie. They are analyzed in painstaking detail by the academic historian Emma Wilby in The Visions of Isobel Gowdie, which is an extraordinary work not only for its mastery of the particular subject, and of the time and place where the events of Gowdie’s trial took place, but also for her thorough, rigorous comparative methodology.

For example, in the case of the Roman myths about the law-giving nymph Egeria and the second Roman king Numa Pompilius, which I talk about in this article on water nymphs:

Wet and wild!

Underwater, by Cristina Coral, from her This Living Hands series (2012-2020). Nymphs are a class of being that too many people today imagine as mere decoration (because they are often depicted this way visually), or, worse — as prizes to be snatched by the sexual predators of the ancient world, which included men, satyrs, and gods.

Fascinating stuff! Something that occurred to me in my first quick reading (I'm in the middle of working on posting my books out!), that I don't *think* you mention, is this: I remember either someone suggesting this to me, or this occurring to me (can't remember which) : that "loose women" might also refer to the kind of woman who wears her hair loose or uncovered. I know that in Irish, British, French society up until the 1950s, repectable adult women would never be seen in public with their hair unbound - ie, not in a bun or chignon or more elaborate coiffure of plaits and loops, etc, and in exterior settings would be almost invariably wearing a hat ; in earlier Irish society (and I believe in Medieval/Early Modern British and French as well), "loose" hair was strongly associated with either a girl-child, a very low-class person, an "uncivilised" person, or indeed a forest-dweller, nymph, or Fae. It is significant too that both mermaids and some "Washer at the Ford" type Beann Sidhe-figures would be combing their loose hair, and even sometimes using the comb as a sharp weapon ; "loose" or "unbound" hair was also associated with private and intimate moments in the bedchamber, at her toilette, or with carnal relations, and therefore prostitutes ... I'm not 100% sure of all of this, but I think I've read/thought about it and it seems to make sense .... What do you say?