Josef Váchal's Pandemonium, Part I

A occult artist's thematic experiments and invitations to enchantment

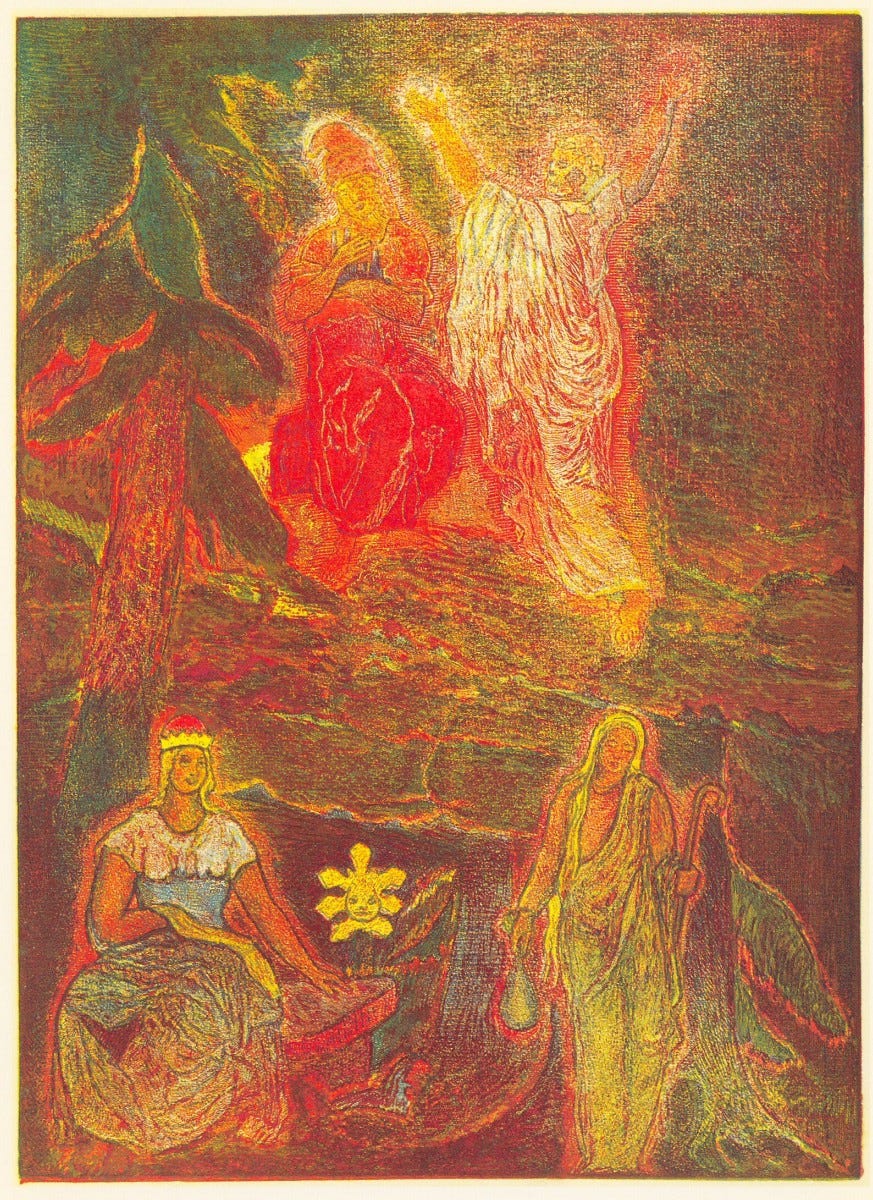

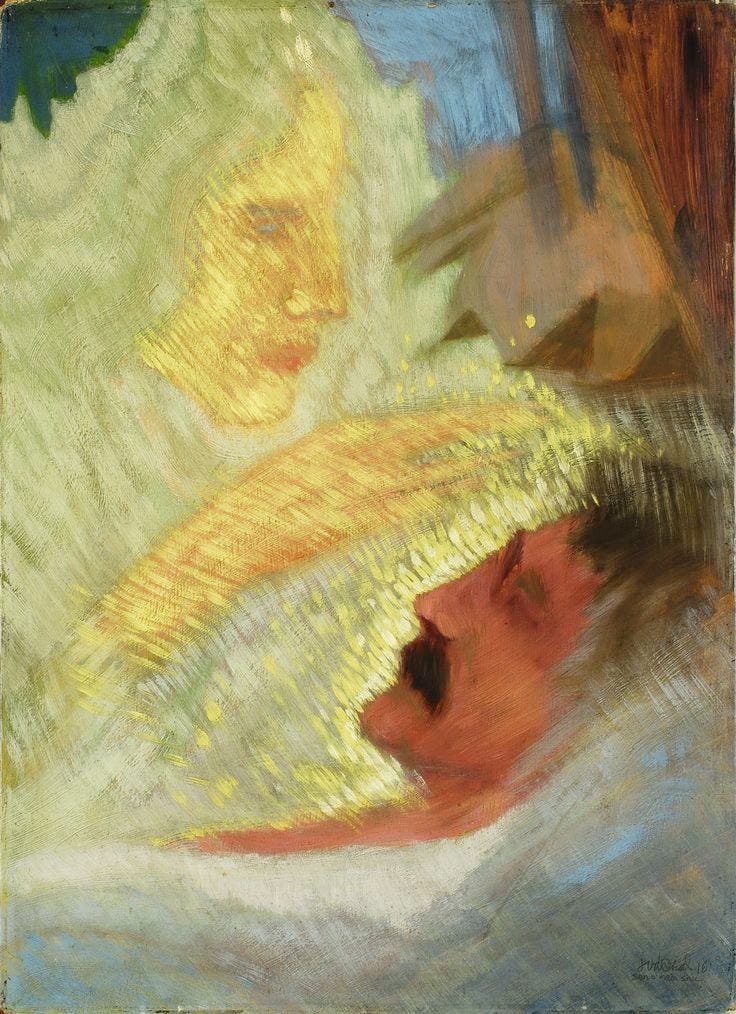

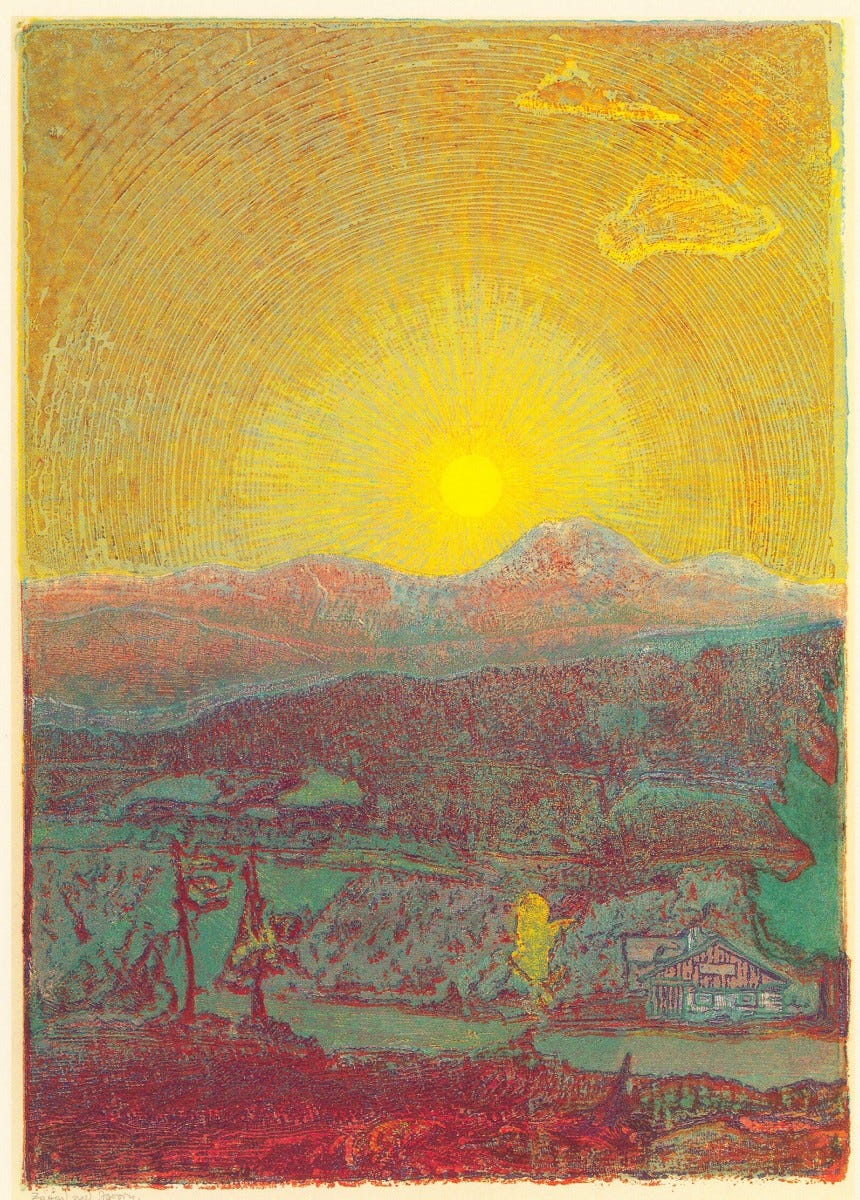

Odcházející krása Šumavy [The Departing Beauty of the Šumava] from Šumava, Dying and Romantic (1931). Source.

Both of these essays are dedicated to my daughter Quintana, a student at Hellichovka Academy of Industrial and Applied Arts in Prague.

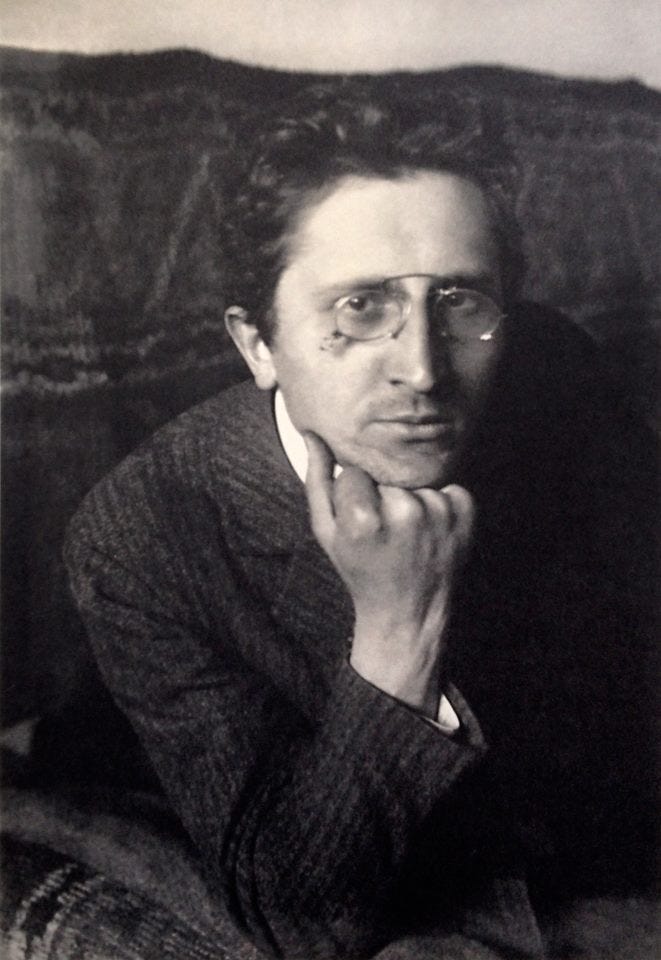

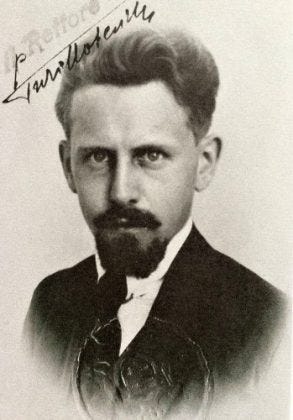

Introducing the Master

When confronting Váchal’s work, a person who sees very little beholds a demon-haunted madman; those with some background in art history find a survey of international styles and trends; and those who try to know things more deeply, recognize that the true depth of this South Bohemian artist’s mastery shows in the doorways through which liminal beings—including him, and you, and me—can pass and have extraordinary encounters.

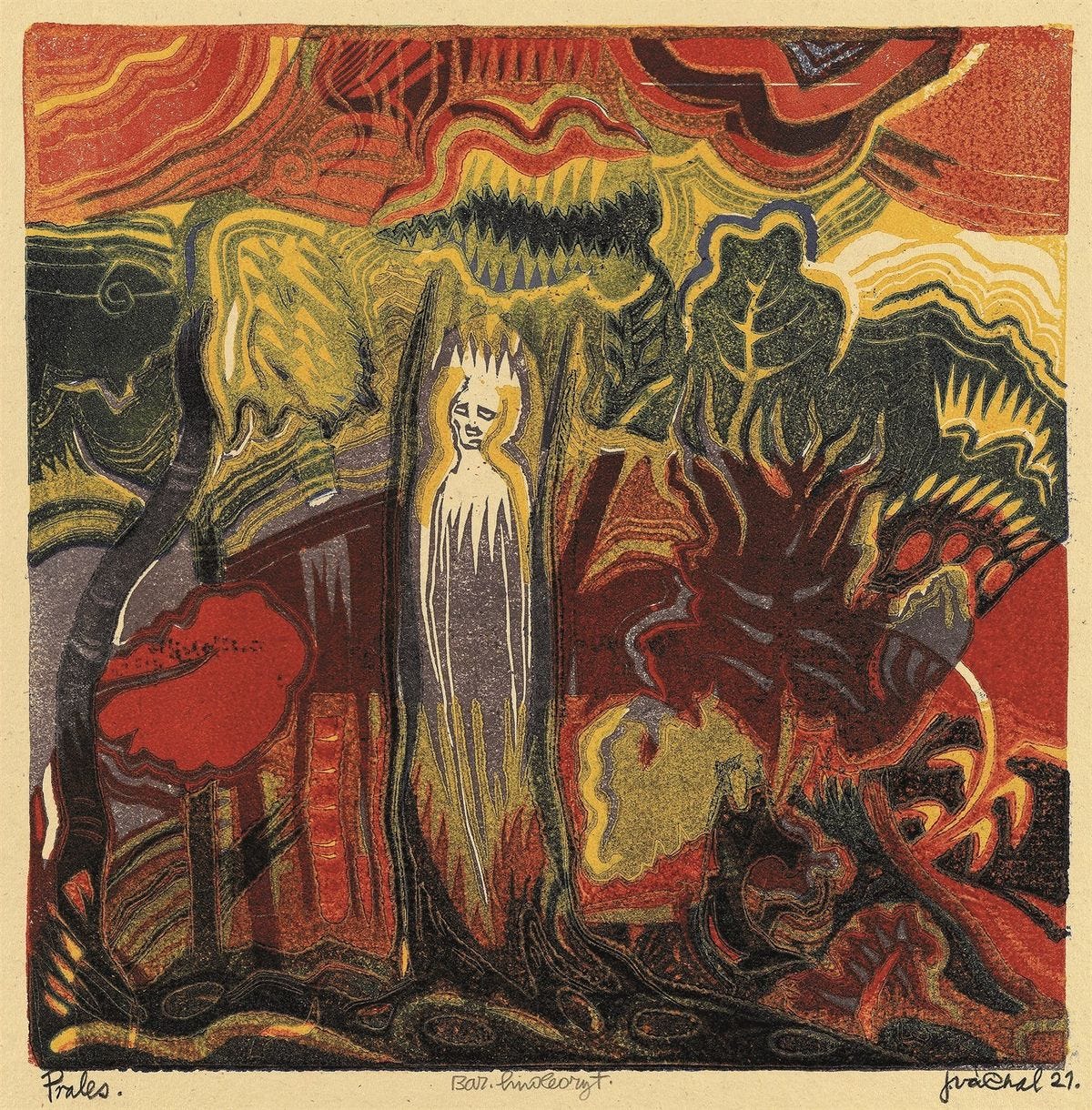

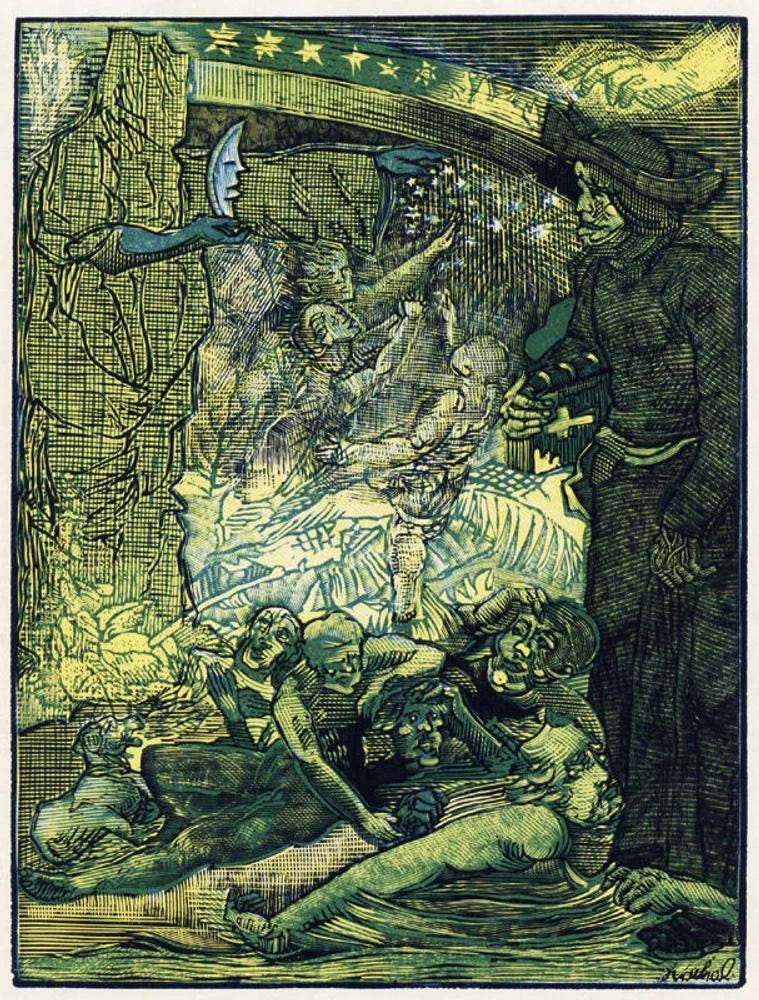

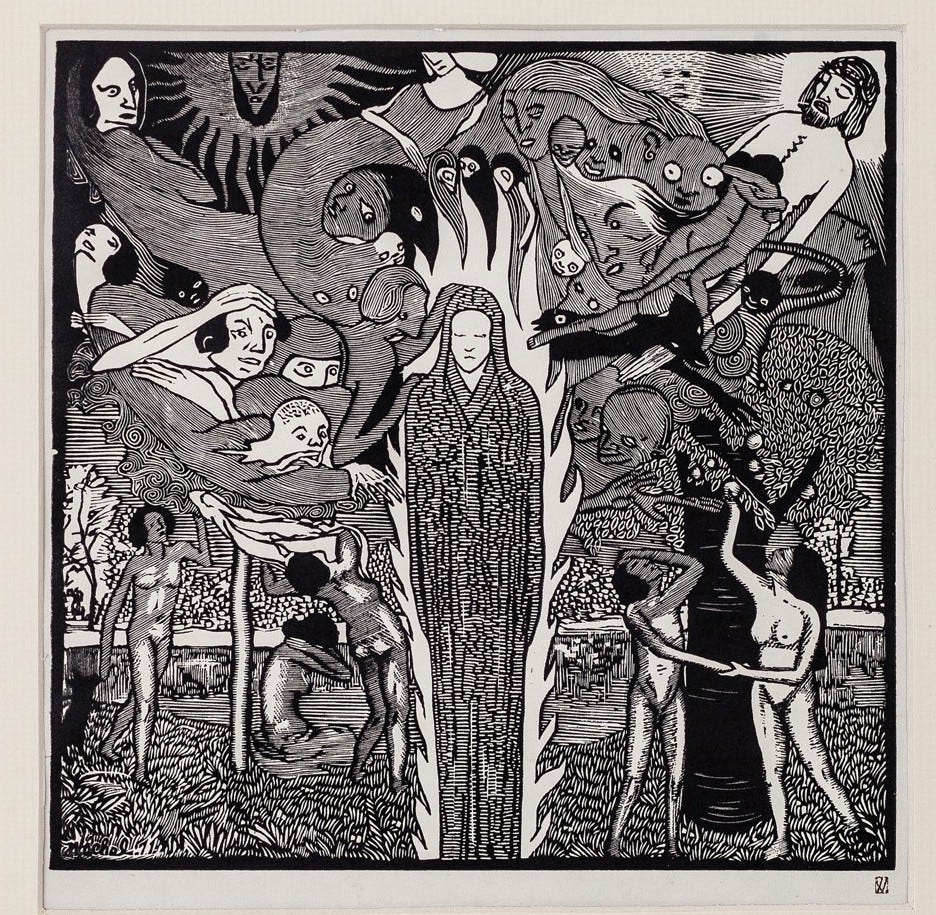

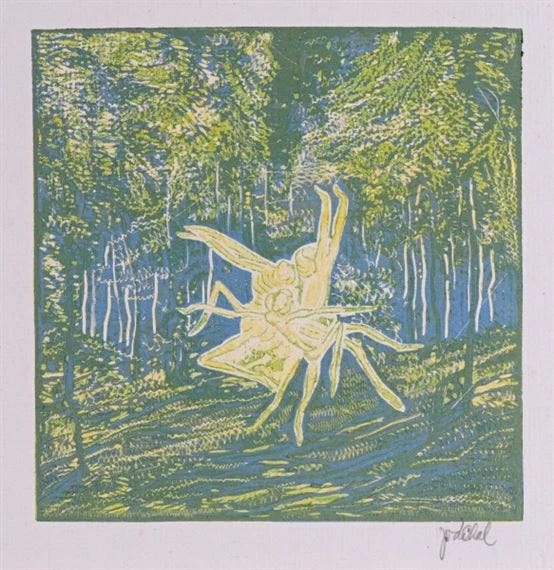

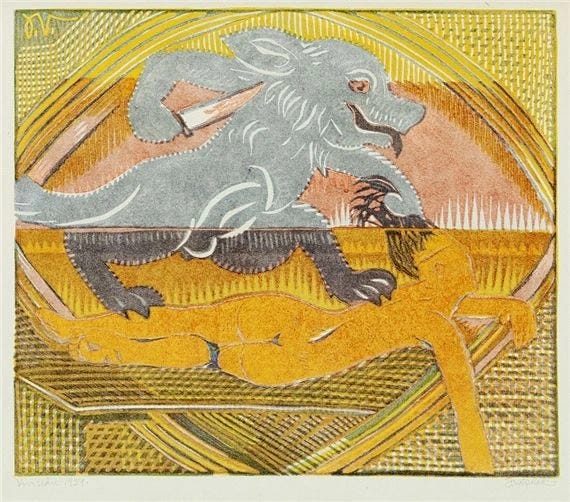

Prales (duch lesa) [Primeval Forest (spirit of the forest)], 1921.

Váchal’s pictures pulse with chthonic vitality; revel in synaesthesia. Crowds of forms explode into orgies of colors that don’t mix together in polite society. The hour is often gloaming, or midnight, or the red hour that sets everything—living, dead, and in between—aflame. The artist luxuriates in forbidden themes, from the diabolical to the grotesquely erotic. Always a provocateur and thoroughgoingly cussed individualist, he took on commissions for “respectable” subjects, the orthodox figures and iconography undermined by the subjects’ ecstatic reveries; yet demonic figures are tamed through accommodation in folklore or through depiction of their habitat in the wild south Bohemian landscape.

There’s filth, rot, and naughty pictures of bare naked laddies and ladies, undergirded by the deeply sane sensibility of a man who cherished his friends, hated violence and politics, and found solace and exultation in what the unknowing thought were the loneliest places. But Váchal wasn’t like the members of mindless mobs, and he was never truly alone: in any place, at every time, whether in a library, a city street, a desolate moorland, or a library was a pandemonium (place where “all the devils” dwell).

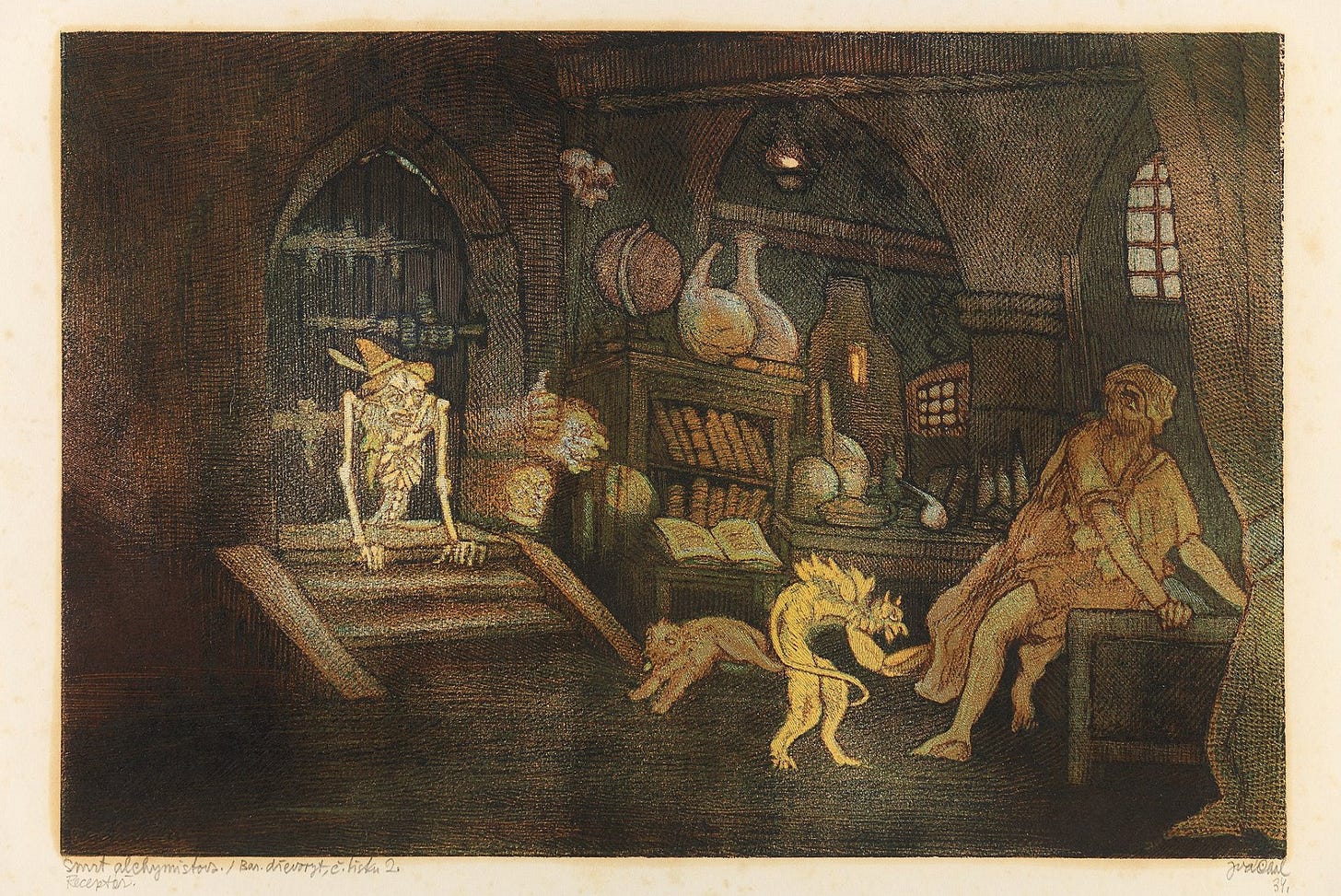

Smrt alchymistova [The Alchemist’s Death], 1934. Image source: Portmoneum.1

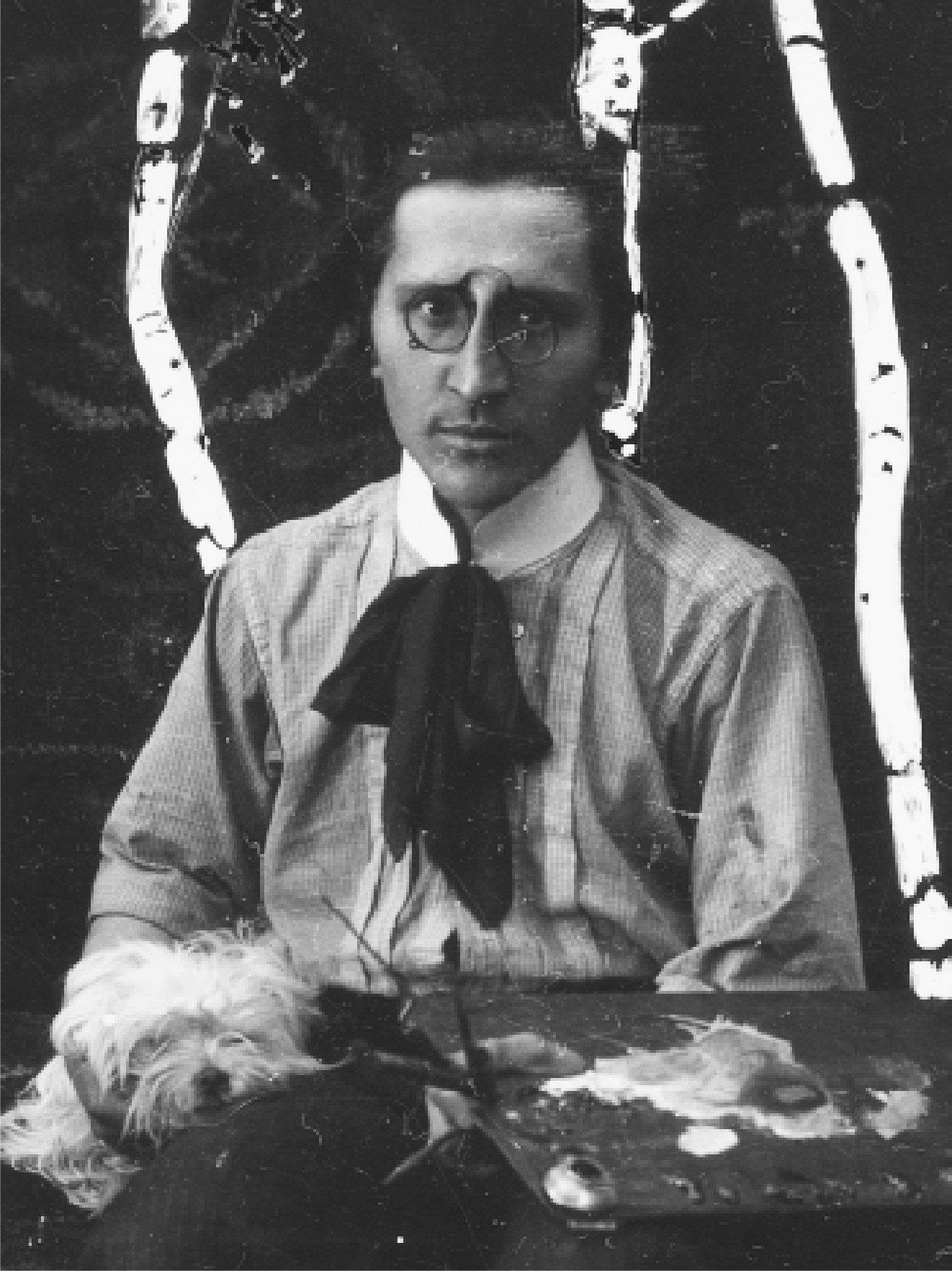

Josef Váchal (1884-1969) was a Czech printmaker, graphic designer, poet and essayist, painter, wood carver, pornographer, and bookbinder — among other things.

Prehistory, woodcarving (undated). Source.

This South Bohemian Renaissance man slipped merrily down the stream of European art trends, taking everything in, and never any of them too seriously. Váchal’s work always shows his fingerprints, while avoiding the limitations of an easily-grasped personal style.

Noc [Night]. Colored woodcut. Source.

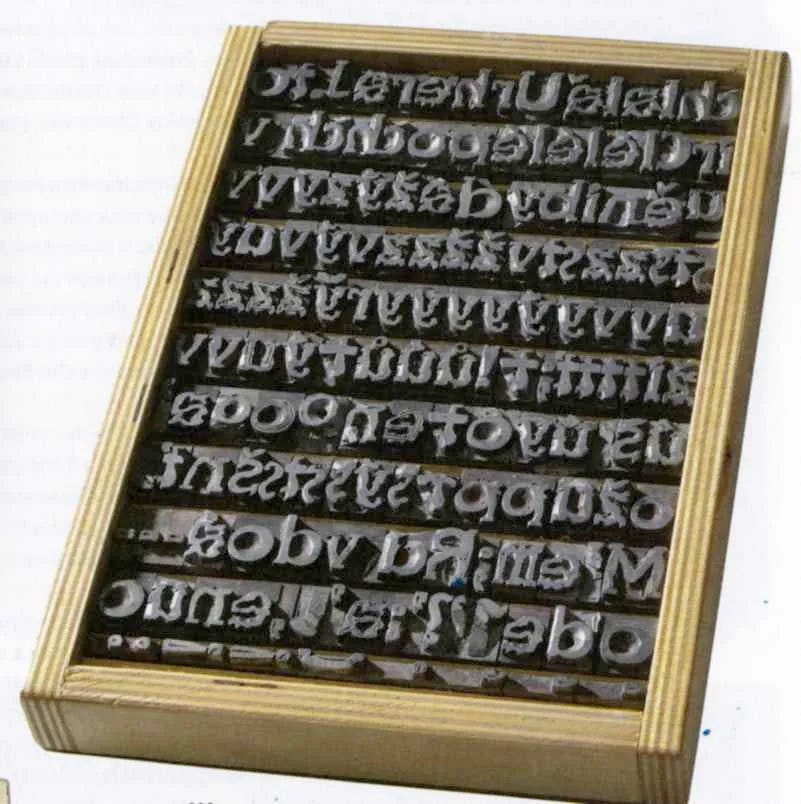

An Artisanal and Individualist Ethos

What truly characterized and distinguished Váchal’s work was the way he handled all the production details himself. For example, when he made a book, he wrote the text, sketched out the illustrations, carved wood blocks not only for the illustrations but also for the lettering, and he bound the sheets of handmade paper himself. Today, we would call this “artisanal” production, and he was every bit the craftsman as well as a fine artist. Whatever Váchal printed was produced in tiny runs, often fewer than 20 pieces. This was just enough copies to distribute among friends and cognoscenti, and too few to attract serious attention from censors.

A page of hand-carved lettering (created in reverse) for one of Váchal’s books. Source.

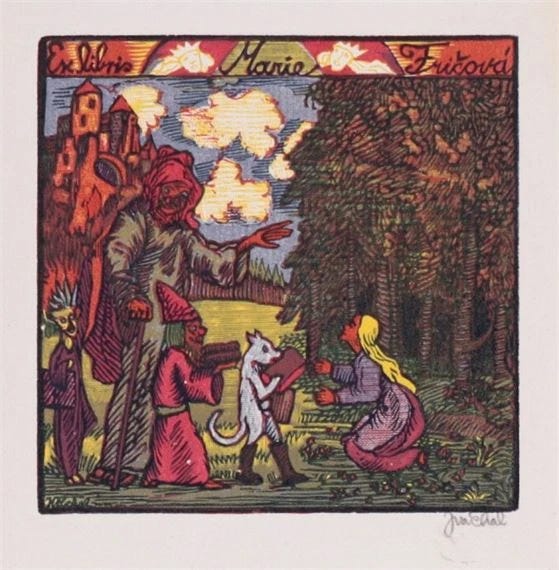

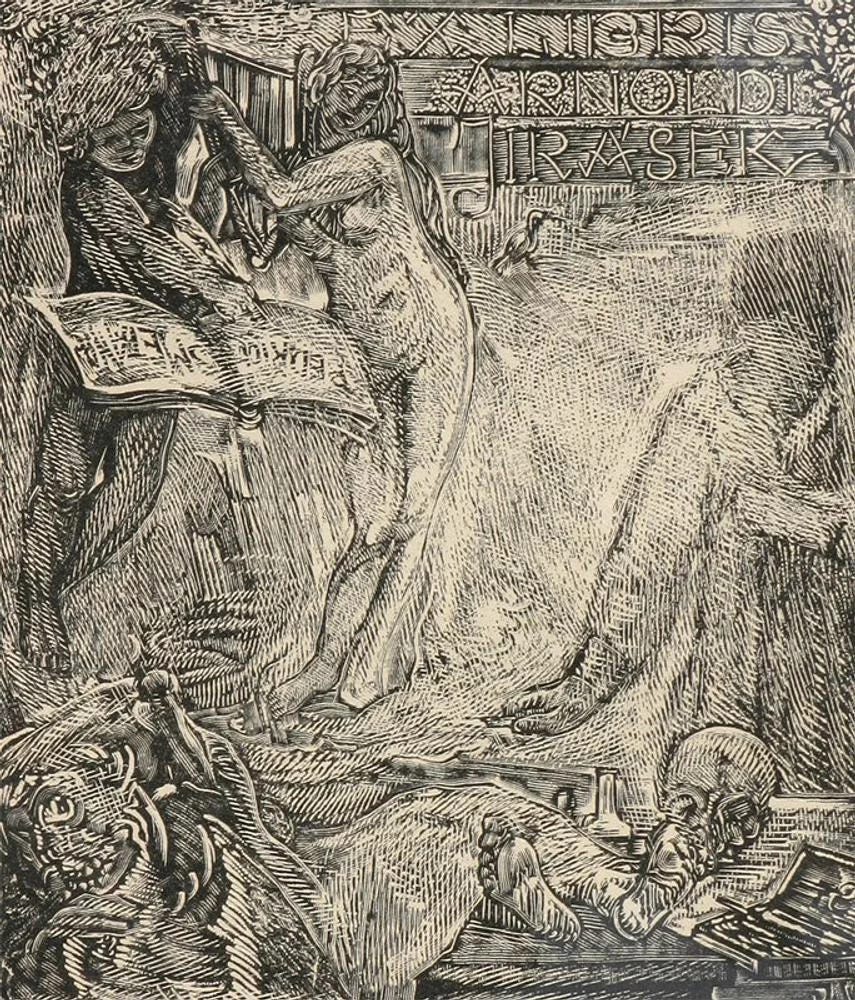

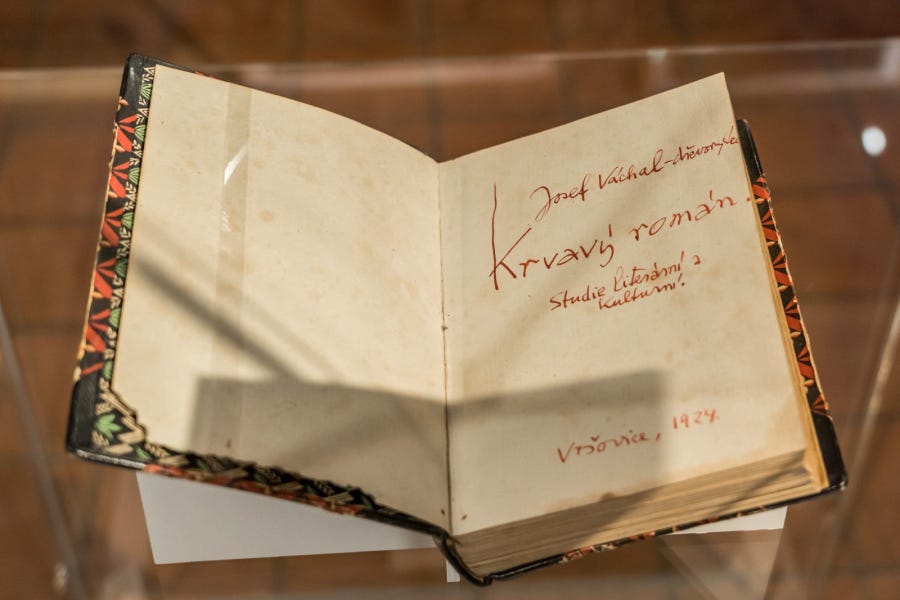

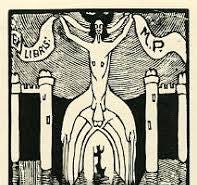

He actively sought out commissions, particularly for South Bohemian landscapes (mountains, streams, forests) and for Ex Libris woodcuts,2 but he did not chase fame or recognition on the domestic or international art scene, and he never bartered his integrity by cooperating with either the Nazi3 or communist regimes, both of which he loathed.4

This uncompromising approach is part of the reason why his work has been underappreciated, not only domestically in the Czech Republic, but also internationally. Publications by and about Váchal are hard to come by in English, outside of a few scanty mentions in art blogs, so I hope this is a delightful new encounter for many of my readers.

His obscurity has also been a product of his sincere pursuit of mysteries, which fell out of fashion in the postwar period. While there has been a recent revival of interest in spiritual art of late, Váchal’s work has mostly been neglected, because it is not as abstract or as surrealist as works the art crowd oohs and aahs over, his Satanism puts many ill at ease, and he only casually quoted from the shorthands of symbols preferred by alternative spiritual movements, which necessitates viewers thinking for themselves what his work “means”—or, rather, what it does.

He subverted every every doctrine and ideology, blasphemed established blasphemies, and exceeded the boundaries of the historical and contemporary artistic styles that he ransacked for ideas.

As much an ethnographer, historian, and folklorist as artist, Váchal sought spiritual education in the wild land of the South Bohemian mountains, in the company of boggarts, devils, and the walking dead, in old tomes on vampires, werewolves and other spooks, in pulp fiction, and in still-buzzing folk tales of deviltry and witchcraft.

Individualism did not allow Váchal to identify with any kind of ideological, spiritual, or political movement for any extended period of time, and he scorned political-artistic movements that promised social and administrative solutions to spiritual malaise. Like many “modernist” artists, he was interested in older artwork, and some “primitivizing” archaisms are present, but, unlike other members of the European avant-garde, “Váchal did not adore the Gothic like the German Expressionists, El Greco like the Central European cubists, or African and Iberian art like the Spanish and French cubists. He sought inspiration in the Baroque Counter-Reformation aesthetic.”5

As an eclectic occultist, he drew inspiration from Theosophy and Christian theology into demonology, Eastern religions and philosophies, and European folklore. In addition to all of this, he was also a zealous defender of penny-dreadful novels against their many critics in clerical and literary circles, and among ordinary moralists who believed adventure stories would tempt readers into vice and violent crime.6 He was a defender of popular culture as real culture, long before such a stance became fashionable.

Váchal’s art and life were of one piece.

Early Life

Baby Josef was born in 1884 to unmarried parents and raised by his grandparents in Písek, South Bohemia. His childhood was lonely, and he enjoyed being outdoors and keeping company with dogs. He did not finish his studies in school, and moved to Prague in 1898. There, he studied bookbinding and took art lessons with his father’s cousin, the painter Mikoláš Aleš.

In 1910, Váchal published his first two books, and in March 1913, he married Máša Pešulová, and began a fateful friendship with the collector J. Portman. His first wife died of tuberculosis, and he would have an intimate partnership with the artist Anna Macková for the rest of his life.

From 1916 to 1918, Váchal served as a soldier on the Italian front: the horrors he witnessed allegedly turned his hair white overnight, as he struggled to stay alive among the still-living, the mortally wounded, and the dead.

Thematic influences

Below, I trace some of the thematic influences that impacted Váchal’s work.

Theosophy

The influence of Theosophy on the international art scene was profound in the fin-de-siecle period and the first third of the 20th century. This was also evident in Bohemia, even in the work of the country’s most famous artist, Alfons Mucha.7

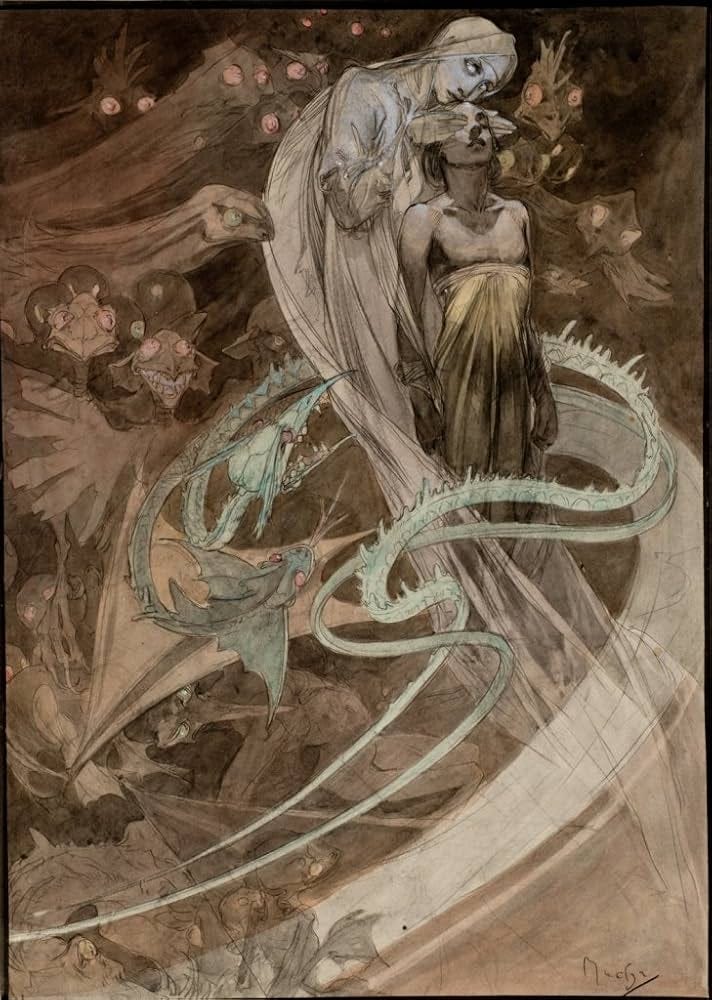

Above: an illustration from Mucha’s Le Pater. Source.

The situation changed after WWII: Symbolism of any kind was no longer in vogue, and artists’ Theosophical inspiration was treated like an embarrassment by critics and scholars. As Waldemar Januszcak wrote, Blavatsky’s movement was was both “fraudulent” and “ridiculous” and was considered a discrediting factor.

The fact is, Theosophy... is embarrassing. If there is one thing you do not want your hardcore modernist to be, it is a member of an occult cult... Theosophy takes art into Dan Brown territory. No serious student of art history wants to touch it.8

Januszczak further claimed that “one day, someone will write a big book on the remarkable influence of Theosophy on modern art” and “its nonsensical spell” on so many modern artists.

However, if that big book is going to be written, it will be in a rather different spirit. In recent years, just as occult influences have been rehabilitated by scholars researching the humanities and sciences, so there is also a renaissance of interest in occult-themed art. This is testified by the growing number of books, articles, and even conferences based on these themes and the increasing popularity of women abstract and surrealist painters (af Klint, Carrington, Miller, Varros, Colquhoun) who were influenced by alternative spiritual trends.

Josef Váchal joined the Theosophical Society chapter in Prague in 1903, and his interest in their teachings waned under the influence of other streams of occult influence. By, at the latest, the 1910s he considered it one of many possible interpretive keys to art, the human psyche, and reality.

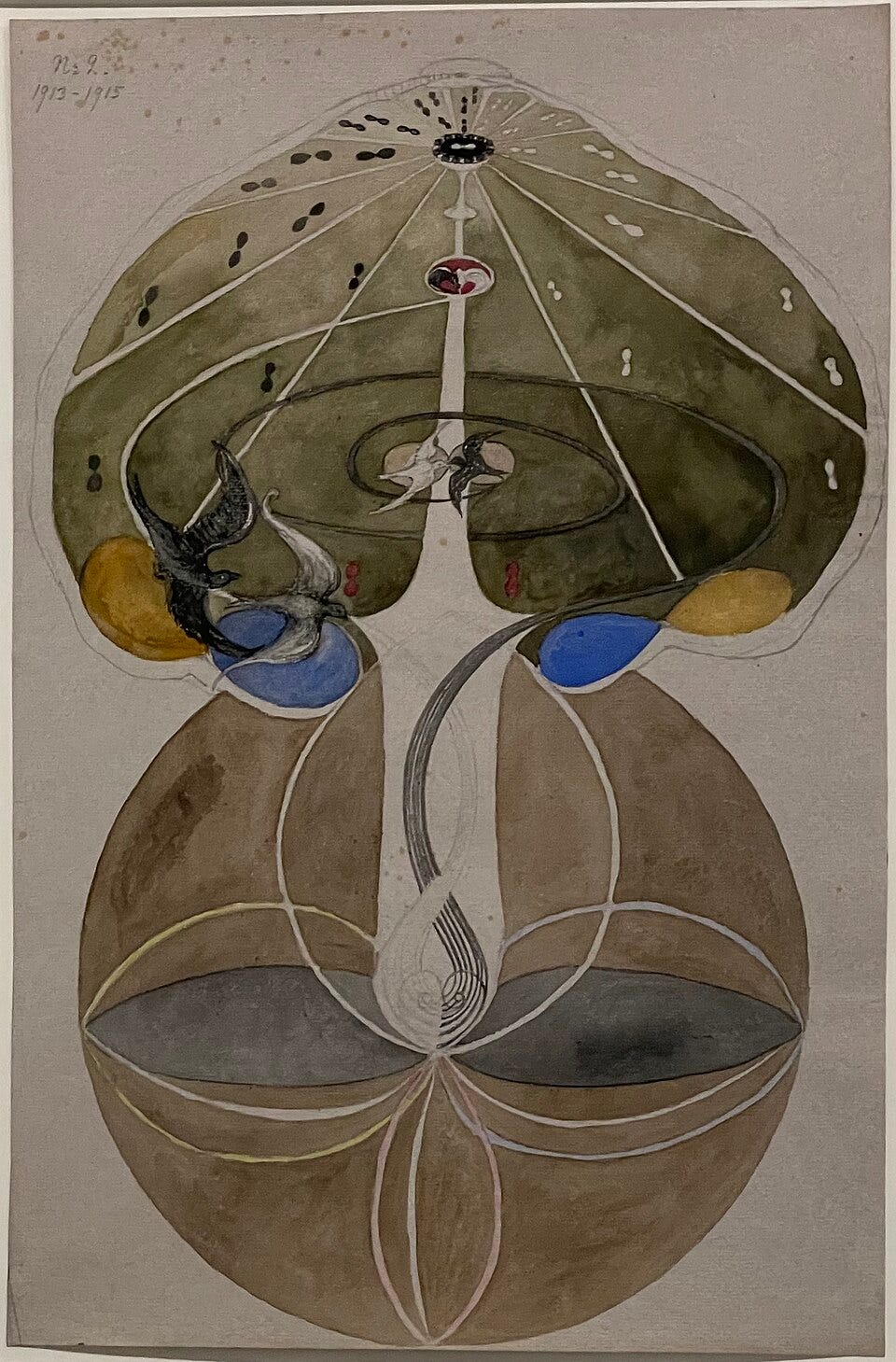

Theosophical art tends to be either very abstract (Hilma af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky) or very schematic, with either more restraint (Piet Mondrian) or more explicit details (certain works by Melchior Lechter). In my unpopular opinion, all of it tends toward a stiff, cold formalism with the charm of a didactic religious text.

Above: Tree of Knowledge No. 2, by Hilma af Klint, 1913-1915. Source: Wikimedia.

Below: Evolution, oil on canvas, Piet Mondrian, 1911. The images, read from left to right, depict a movement from the material to the spiritual, in accordance with Theosophical teachings. Source.

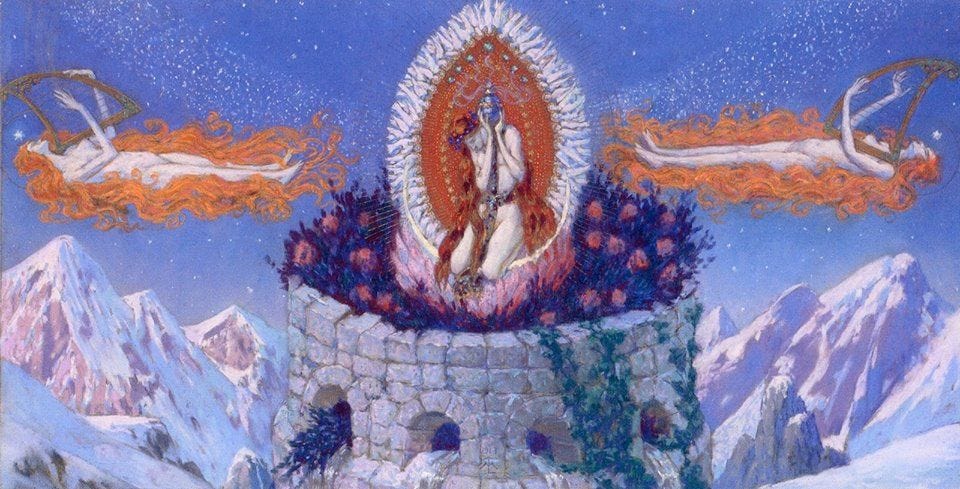

Below: Sacred Tower in the Mountains with the Four Sources of the Stream of Life, Melchior Lechter, 1917.

We might also compare (or, rather, contrast) Váchal’s work with the oeuvre of the Czech abstract painter František Kupka, who dispenses with the didactic baggage of Symbolism.

Study for the Language of Verticals, František Kupka. Oil on canvas, 1911. Source.

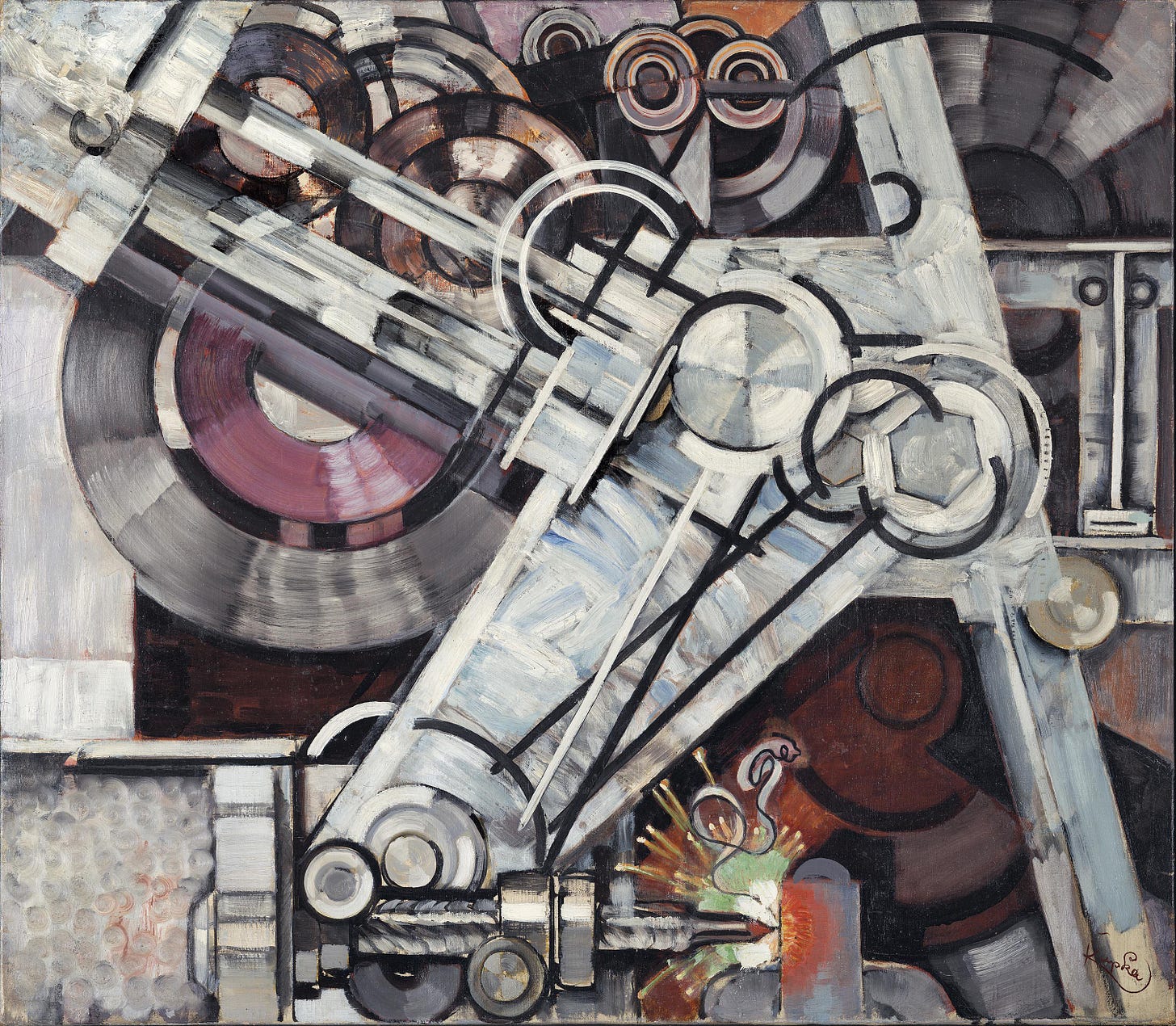

Kupka was also influenced by Theosophy and its color theories, and he was a practicing spiritualist medium. However, there is a specificity, an earthiness and a sense that the “ spiritual” is actually about spirits, whether they come from dreams, from potions, or are indwelling forces in the land, that—in my opinion—makes Váchal’s work far richer and more imaginative than Kupka’s could even aspire to be.

Blue Ribbed Arches II. František Kupka. Oil on canvas, 1920-21. Source. This piece by Kupka has strong rhythm and spaciousness, and it is pretty, but its heady idealism is rather sterile, instead of teeming with generative powers as Váchal’s work usually does.

Above: The Machine Drill, by František Kupka. Oil on canvas, 1927-29. Source. It looks like a late echo of Cubism, but actually Kupka was best known for his entirely nonrepresentational art.

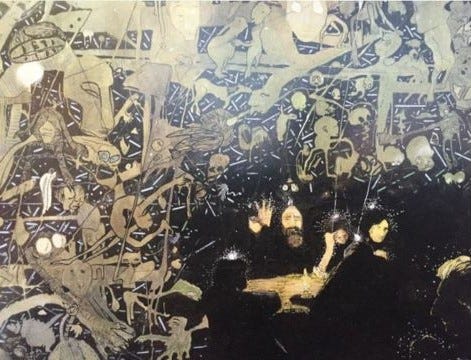

In this part of the murals inside the Portmoneum in Litomyšl, a curator notes the similarity between Váchal‘s and Kupka’s abstraction:

“For work purposes, I dubbed this part [of the murals] ‘Kupka’s Fugue,’ says Látal, pointing to a section of the painting that truly does resemble the only slightly more recent picture Fugue in Two Colors by František Kupka, the Czech painter whose pictures sell for the highest prices.” Source.

Disks of Newton (Study for Fugue in Two Colors) by František Kupka, 1912.

Cubism and abstraction replaced many older painting styles and dreamy introspection and symbolism were no longer in style in avant-garde circles. As industrial modernity and scientific perspectives gained prominence, photography took over documentary functions, so painting was expected to fulfil new roles.

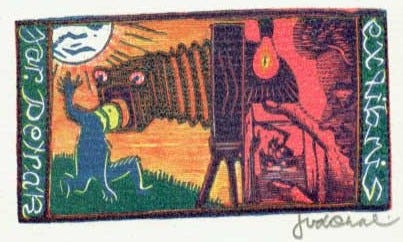

But where does that leave magic?

Above: a whimsical Ex Libris with a camera and darkroom.

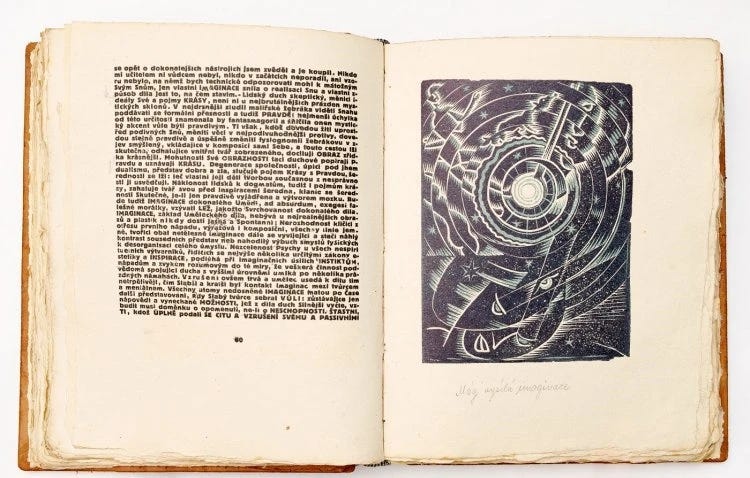

Below: A two-page spread from Váchal’s “Perfect Magic of the Future” in English. Some of the the illustrations have passing similarity to the formal experiments of artists working in Cubist styles, but they still retain a dreamlike ambience. Image source.9

Although Váchal had been involved in Theosophical and Spiritualist circles, he applied the insights from these groups in his paradigmatically individualist ways.

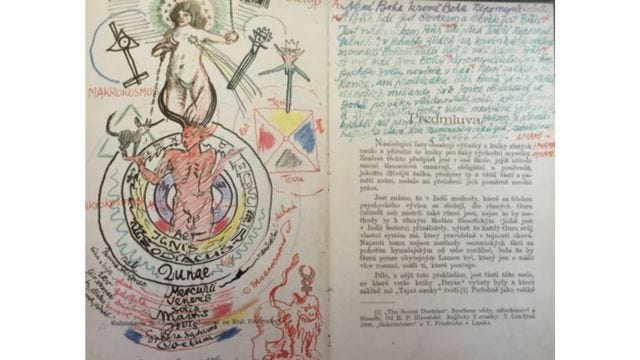

Váchal’s doodles and notes in his copy of Blavatsky’s Foundation of Indian Mysticism shows astrological, alchemical, Theosophical, Satanic, and erotic motifs. Source.

Theosophists have an uneasy relationship with this casual approach, as they believe the transcendent truths in their system ought to be both self-evident and preferable to any others.

The official Theosophical Society logo. Wikimedia.

Secret Societies

What about secret societies? One contemporary Theosophical writer claims, “By the time he decorated the Portmoneum, Váchal had become critical of certain secret societies, and one of the murals alludes to the dangers and shortcomings of some of them …. [in one of the murals in the Portmoneum] … another image celebrates the Theosophical unity of all great religions, a pacifying theme overcoming the dangers of the occult.” Source.

I take this claim with a fist-sized chunk of salt.

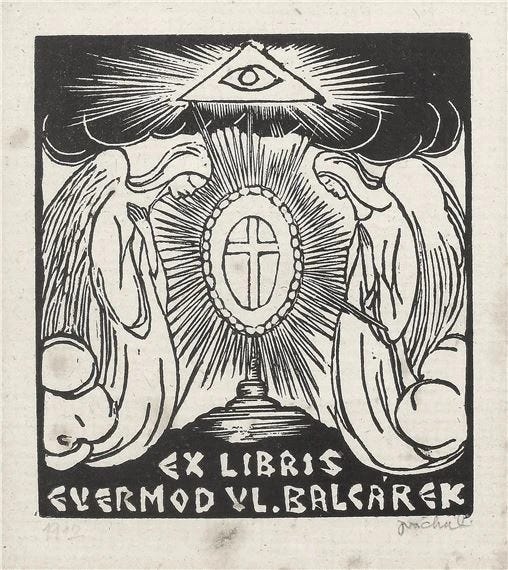

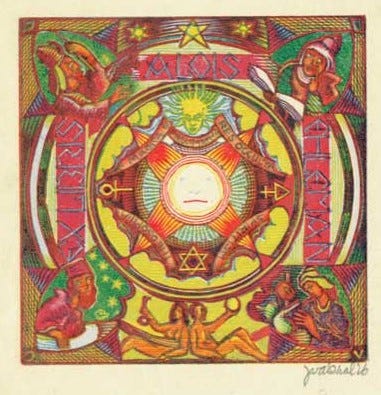

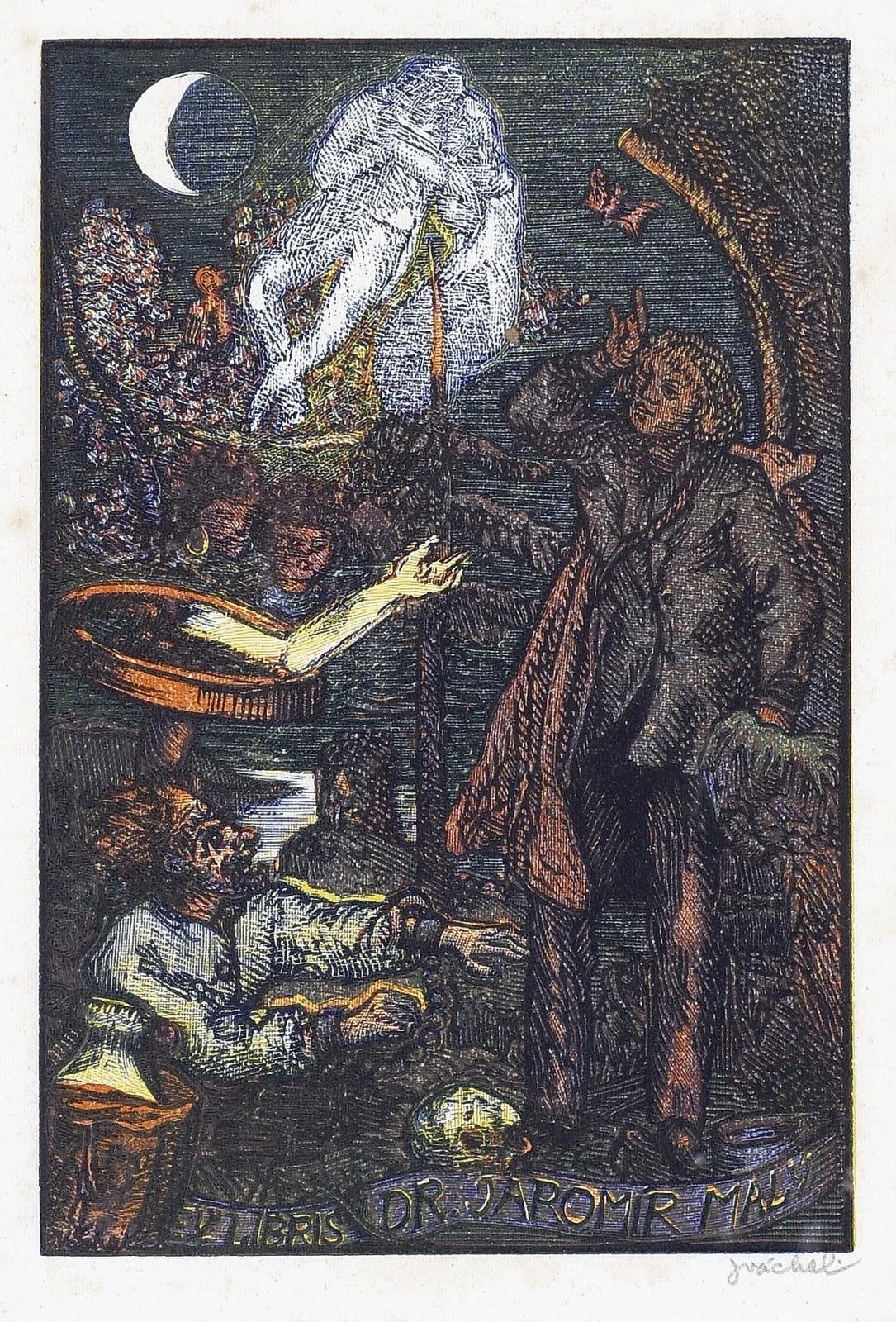

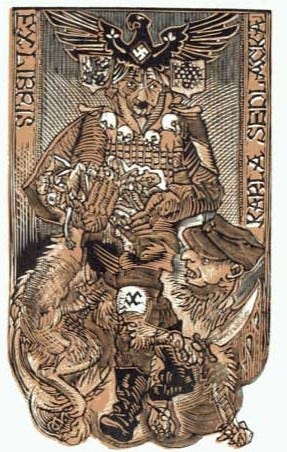

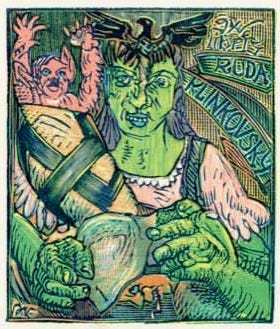

The Eye of Providence was a symbol of the Bavarian Illuminati as well as Freemasons in Europe. Since Ex Libris commissions were at the request of patrons, it is difficult to know what inspired Váchal when he made this woodcut. Source.

Another Ex Libris, from 1926. Source.

One more Ex Libris with symbols of occult societies, from the same collection.

Christianity

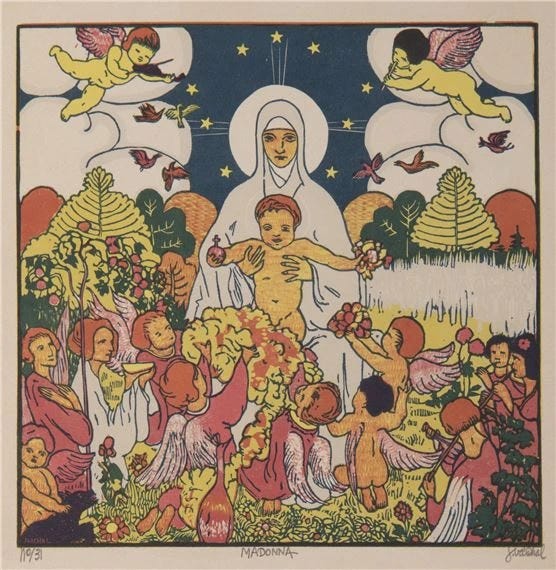

The Madonna wood block print (1912), is one of Váchal’s few pictures that presents an unambiguously orthodox point of view. Source.

In just about all other cases, when he worked with Christian motifs, the traditional figures and symbols are combined with esoteric, folkoric, or even macabre elements. Terror and death, inspiration, demonic oompah bands (in St. Anthony) and neurosis and stigmata (St. Anne Catherine Emmerich) make for an unsettling brew.

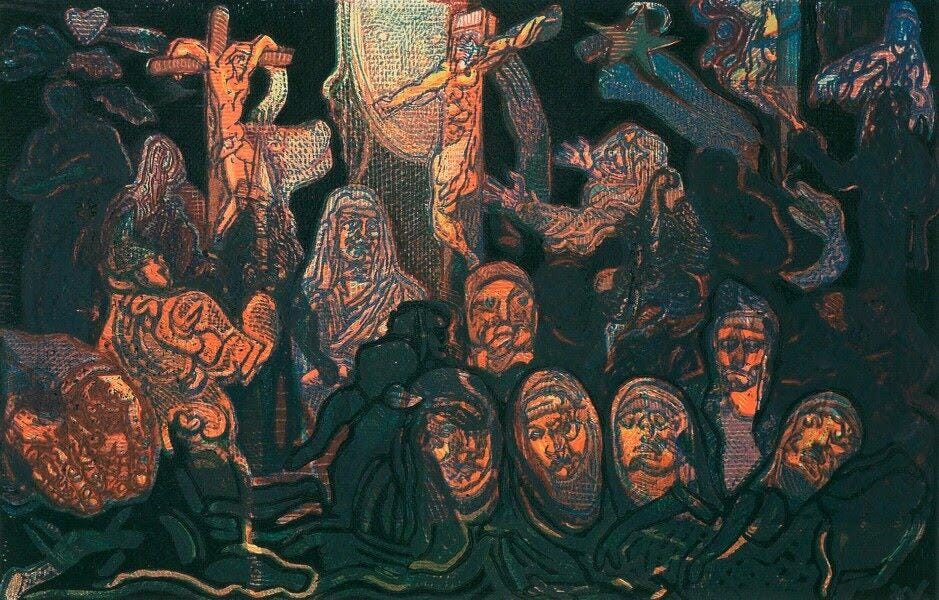

Above: Calvary Golgotha, woodcut, 1919. Source.

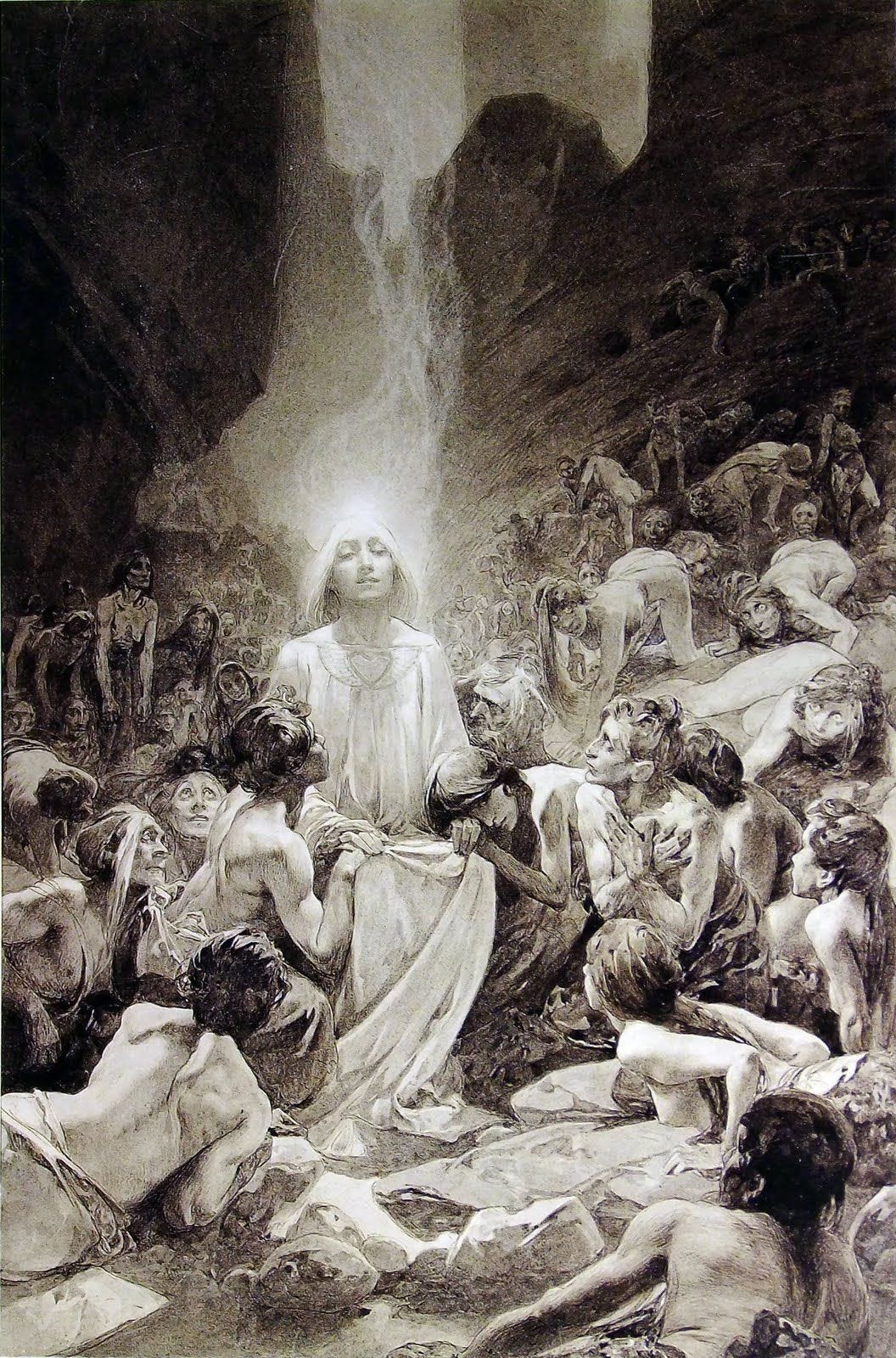

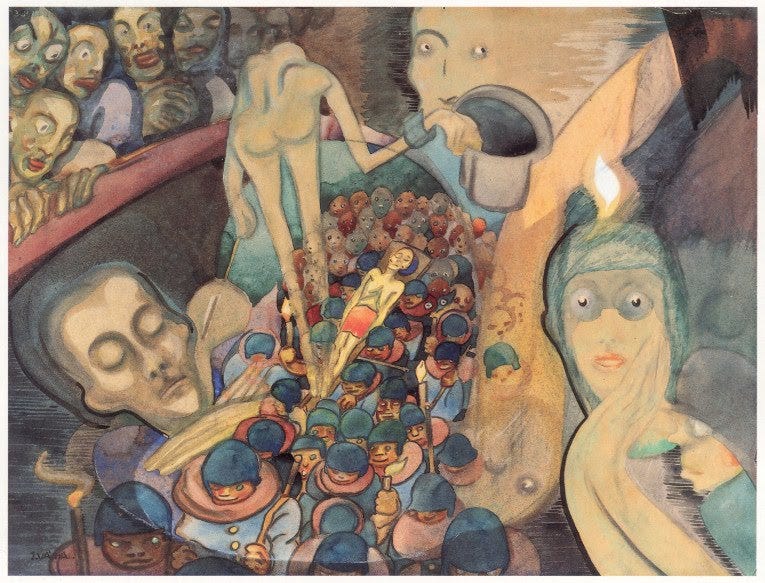

Many of his religious protagonists figures are not contemplating salvation and a heavenly afterlife, but rather experiencing torment or rapture, or the events taking place around them are beyond their ability to comprehend.

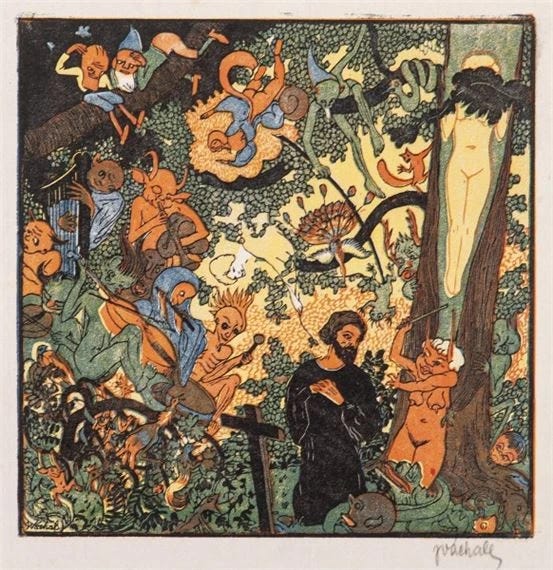

Temptation of St. Anthony, colored woodcut. Source.

For this reason, it’s not surprising that he is more inclined toward depicting Christian mystics than the usual Nativities, Crucifixions, or Pietàs.

Above: Anne Catherine Emmerich, from the collection of nine prints titled Mystics and Visionaries (1913). Source. Emmerich was too poor to be accepted at a convent; however, thanks to her visions and to her stigmata, she still became a notable religious figure, and she was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2004. More here.

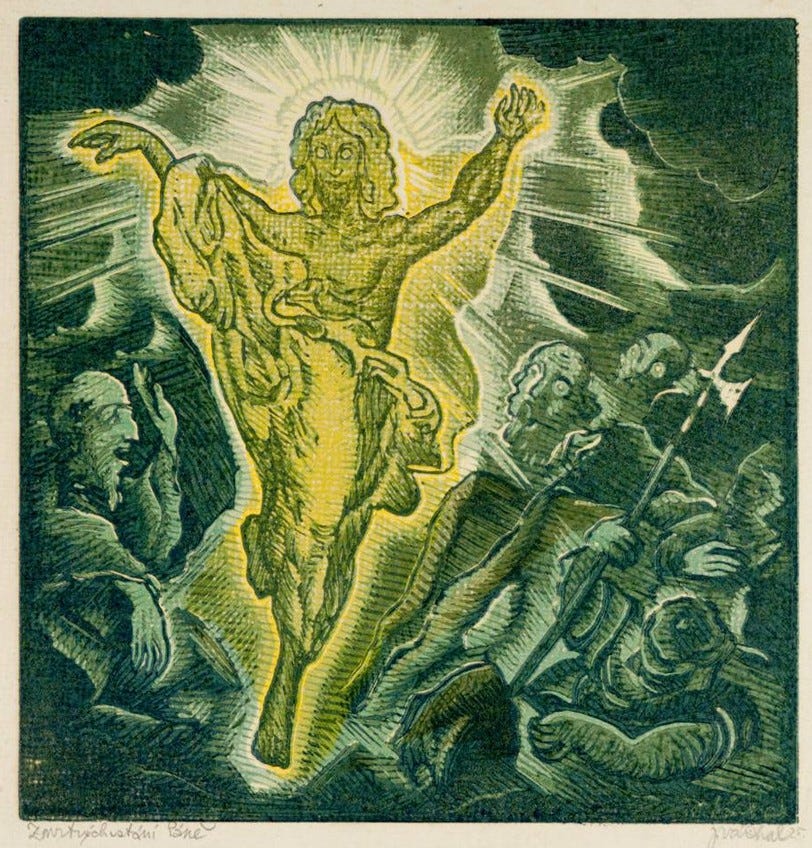

This illustration of Christ’s resurrection is downright frightening. Why does he depict him this way? My interpretation is that Jesus lacked the kind of habitat or ecosystem of the spooks Váchal found in woods and moorlands, and was at home only in his followers’ psyches, which were inadequate to contain him, so his image terrified them.

Source.

On the other hand, Váchal had a sincere love for animals, and the goodness of St. Francis is depicted through his ability to mentally connect with the various creatures.10

Above: Svatý František dobráček [St. Francis the Good], colored woodcut, 1953. Source.

Bohemian Decadence

Bohemia had a notable branch of the Decadent movement11 — an artistic wave that was a kind of proto-Surrealism, or, alternately, the edgier side of Symbolism whose style was dandy and whose spiritual yearnings were occult.

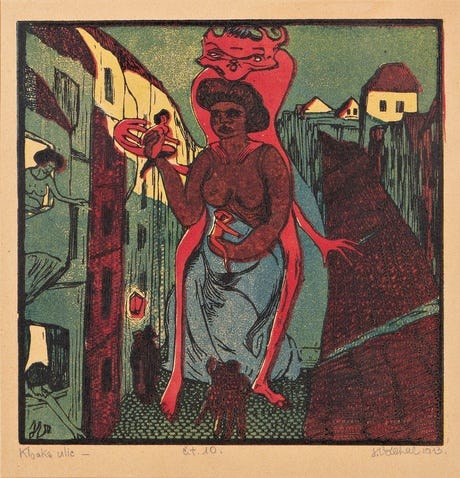

Kloaka ulic (Street Sewer), 1913, woodcut. Source.

According to the definition in Decadence: In Morbid Colours—Art and the Idea of Decadence in the Bohemian Lands 1880-1914, (2006), the movement was born from a “bizarre, fin-de-siècle amalgam of dandyism, occultism and Symbolism, Decadence moved the Romantic imagination firmly indoors, into a morbid, mauve-hued interior with Redon on the walls and Poe on the bookshelves.”

The Decadents reveled in provocation, and promoted the cult of the aesthetic and the artificial, while disparaging tradition and familial commitments and turning their back on the Romantics’ vistas of nature. They were open to experimentation with sexual “perversions” and drug use, and lionized wealthy, beautiful, but self-destructive individuals.

Because of his frequent depictions of sex and death, Váchal is sometimes classified as a Decadent, but he was a poor fit for the movement otherwise. His interests in many ways diverged from those of the other artists in this movement, and he wasn’t nearly so weary. Ultimately, Decadence was a dark form of humanism, as it centered human fantasies and the pursuit of aesthetic hedonism and it was (at best) indifferent to the question of preserving natural and traditional rural landscapes and folk culture, and favored luxury over simplicity and glamor over craftsmanship, and Váchal was not indifferent to any of these issues.

Witches

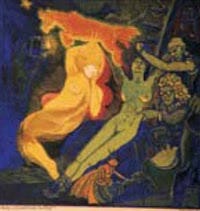

Čarodějnice [Witches]. Oil on canvas, 1915.

Above: another image of witches; this one is from Bez názvu (from Čarodějnická kuchyně)

The image above is from the Preface of his book Mystics and Visionaries (1913). It could equally be a witch burning at the stake, or a visionary “on fire” with her insights, resisting both worldly and spiritual temptations.

Below: Smrt čarodějnice [Death of a Witch], undated. Source.

Alchemical Manuscripts and Marginalia

An Ex Libris in which a sober-looking businessman is unfazed by fantastical figures engaging in some kind of ritual. The sphinx-scribe lying on the ground seems to have Váchal’s face. Source.

This wooden cabinet is painted with figures that look like they could have come from a medieval or Renaissance illuminated manuscript. Source: Portmoneum Facebook page.

Demonolatry, Folk Devils, and Infernal Themes

Any casual mention of Váchal and his work will mention his Satanism, though it is important to also give regard to differences between the references to a theological Satan, and folk devils. Complicating the matter, “esoteric allusions are often treated with the artist’s signature humor.”

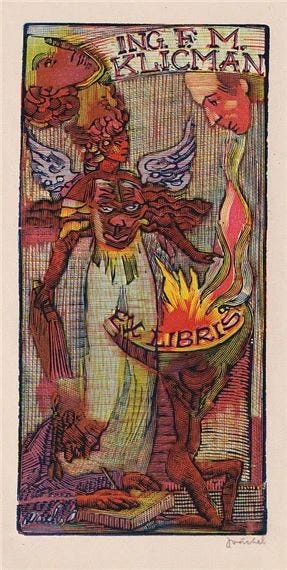

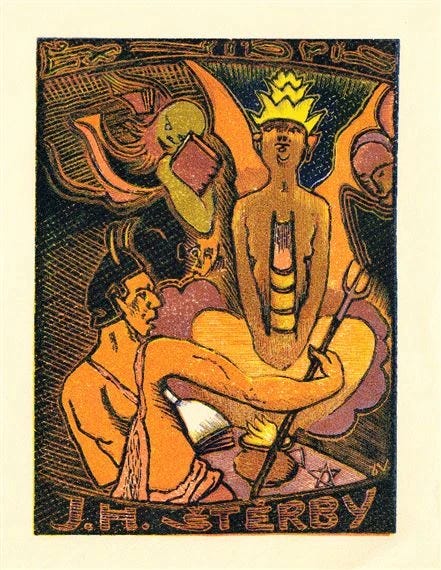

In addition to his own explorations, Váchal had also been influenced by the Polish novelist Stanisław Przybyszewski (1868–1927), one of the forefathers of 20th century Satanism (source). Nevertheless, he still doesn’t take it all that seriously, and sometimes he also combines it with erotic motifs, like the scholarly adept in the Ex Libris (below) whose book looks suspiciously like a phallus.

Ex Libris for J.H. Štěrby, 1938. Source. Has there ever been a more apt image of the true bibliophile?

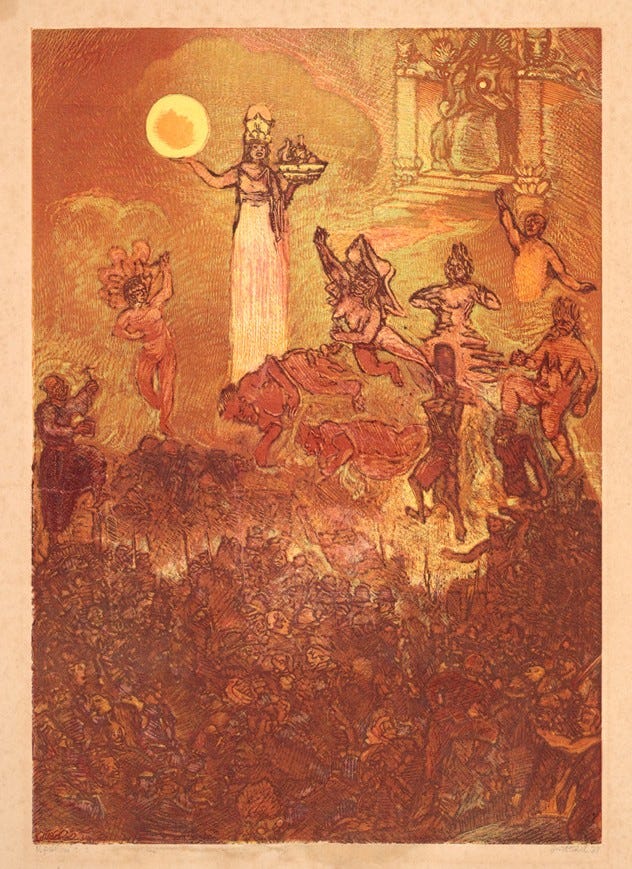

Satanic Invocation, 1909. Source. (Note the skulls on the trees!)

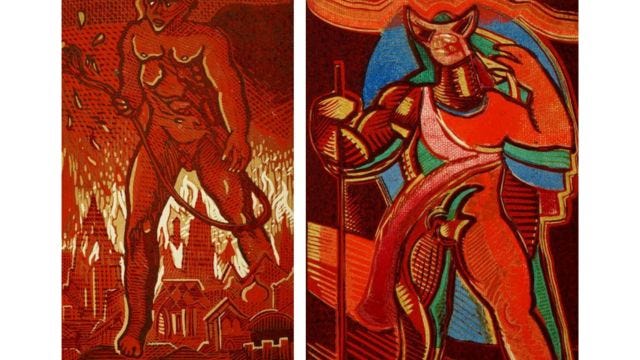

In 1926, Váchal produced seventeen copies of an edition of the Italian poet Giosuè Carducci’s “Hymn to Satan,” which he illustrated. While the poem was not based in theological Satanism (it was actually originally written as a dinnertime toast, and is a paean to rationalism rather than diabolism), Váchal interpreted Carducci’s Satan through the lens of Blavatsky’s comments on Lucifer. The book has become very collectible, even in international art auctions. Source.

Hail, O Satan

O rebellion,

O you avenging force

of human reason!

Let holy incense

and prayers rise to you!

You have utterly vanquished

the Jehova of the Priests.

The above text is an excerpt; the full text of Carducci’s poem can be found here.

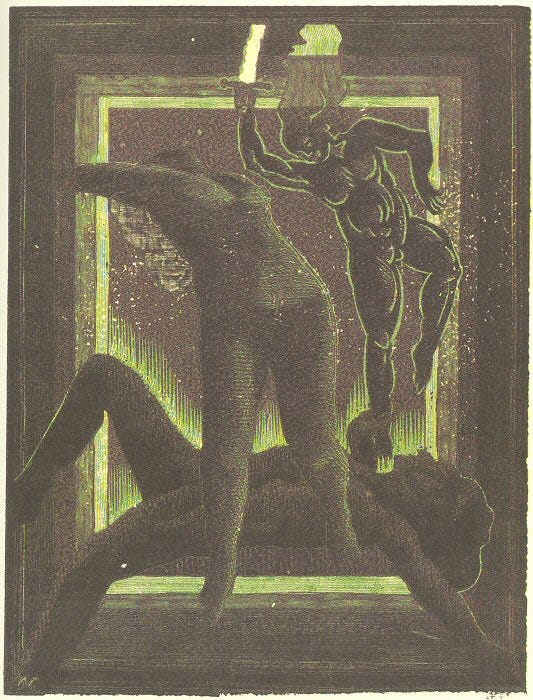

Illustrations created for Carducci’s “Hymn to Satan.”

Above: Black Mass. Woodcut. Colored versions of this print also exist, but the figures are less legible. Source.

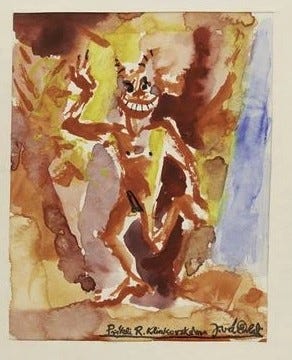

Below: a happy little ithyphallic devil. Source.

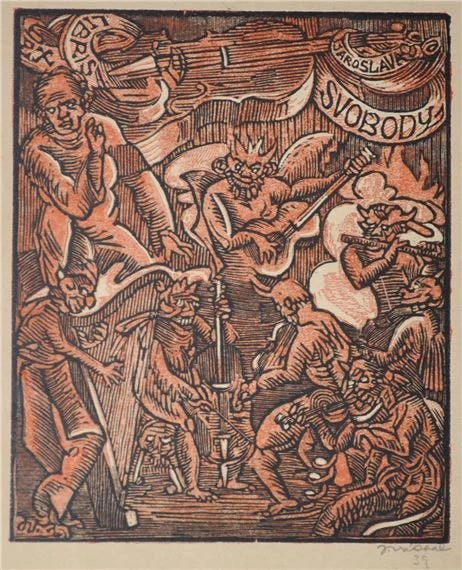

Above: Ex Libris titled Pekelný orchestr [Infernal Orchestra]. Source.

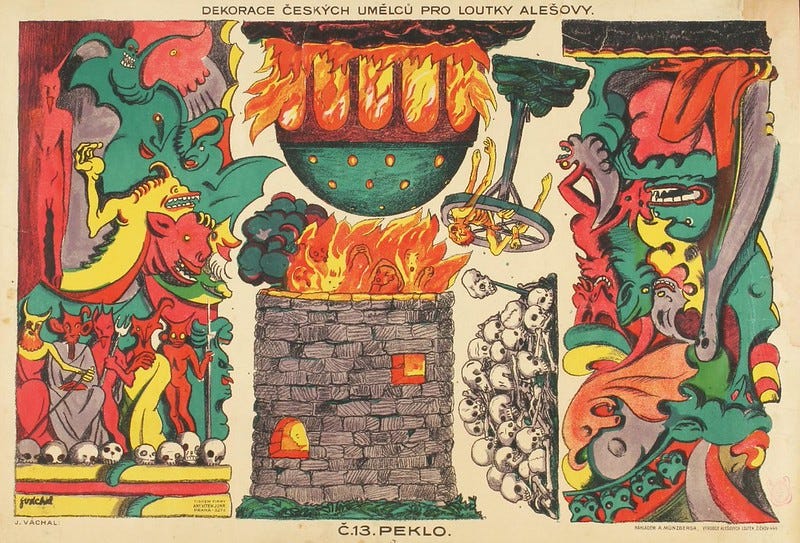

The woodcut below looks like Váchal was experimenting with a visual vocabulary for devil heads, with elements that seem to come from non-Western art, Bohemian puppets, and silhouette papercuts. Bohemians, like other Central Europeans, do not have the fear of “devils” that many had in the English-speaking world. Many are familiar with the Austrian tradition of Krampus frightening children, but in Czech culture it’s “the devil” or “devils” who do this. In Czech folktales and performances for children (e.g. puppet shows), “devils” are selfish but a bit dim, and are easily outwitted.

Source.

Below: Váchal’s sketches of “Hell” included in a collection of “Decorations by Czech Artists for Aleš’s Puppets.” Source.

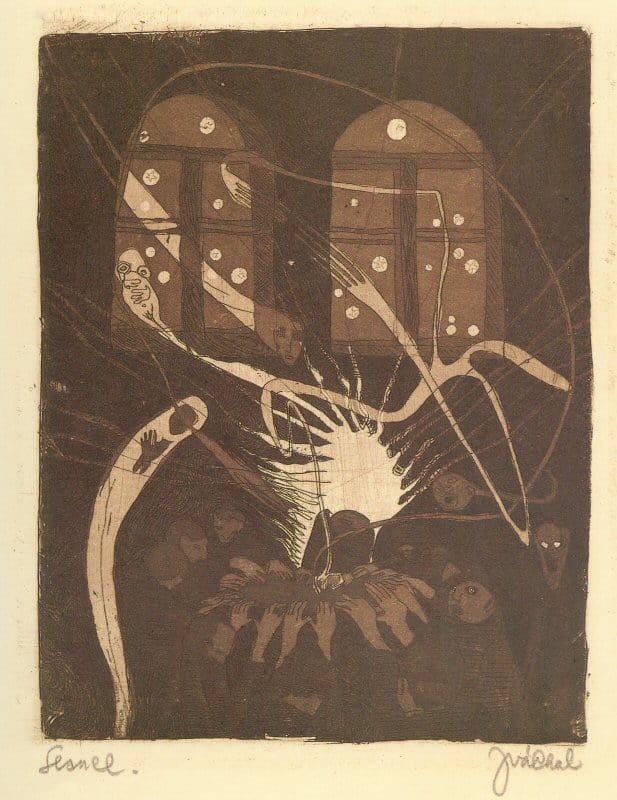

Dreams

Sen [Dream], undated. Source.

Dreams and reveries were a source of inspiration that often facilitated other mystical modes and encounters, though they could ultimately become merely self-referential.

A Walpurgis Night’s Dream, woodcut 1914. Source. Here we see dreams and witches combined in one image.

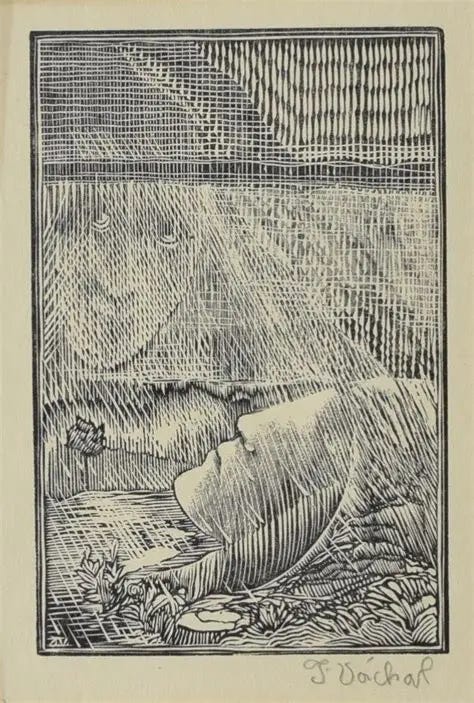

Sen mrtvého [Dead Man’s Dream], 1918. Source.

Sen mého snu [Dream of My Dream], 1916. Source.

Spiritualist Séances and the Living Dead

In his early years, Váchal participated in Spiritualist gatherings hosted by the Theosophist and sculptor Ladislav Jan Šaloun in his Prague studio. After participating in Šaloun’s séances, Váchal started experiencing nocturnal sightings and hearings of beings with misty bodies and feelings of horrible fear when he was alone, but the cure for these disturbing visitations was not to retreat to the Church or to shut them out, but to—as people now say— “do the shadow work.”

He later reported, “only when I began to occupy myself with Spiritualism and even with the Devil, my fear ceased.” Source.

Josef Váchal, Spiritualist Séance, ca 1904–6.

Séance. Source.

In the period between his Spiritualist years and the publication of Šumava, Dying and Romantic (1931), Váchal produced a painting with a hanged man positioned at a distance from civilization, exposed to a magnificent view and dawn- or sunset-tinted clouds. Exile? Suicide? Execution? It’s hard to say.

Krajina s oběšencem [Landscape with a Hanged Man], oil, prior to 1914. According to the auction page that sold this piece, it marks the period when Váchal rejected the Catholic influence of some of his associates during the Sursum years (see Footnote #11). While the art historians comment on a “decadent aesthetic influenced by anarchism,” I disagree. However, their claim that his work in this period was impacted by reading Schopenhauer and Nietzsche seems likely. They also make the contrasting point that, unlike with the artists from the Moderní revue circle, the primitivism and raw expression in Váchal’s work rejected aestheticization and paraphrased some of the Art Nouveau landscape style of his Impressionist teacher Alois Kalvoda.

Theosophists might read the hanged man as symbolizing separation of the astral and physical bodies, and the clouds as a sign of renewal, and blah blah blah, but in my opinion it’s unlikely this was the artist’s intention, given that he clearly doesn’t see death as only a gateway to “higher realms” or to the soul’s rebirth into another body. Source.

Often, the dead in Váchal’s were not just inert bodies bereft of some essential soul-part that had departed to an astral plane, and they certainly didn’t look like the kind of company that genteel Spiritualists would invite to rap on tables in their dining rooms: these figures possessed an unsettling corporeal reality. Neither zombies who were enslaved wretches, nor revenants pursuing unfinished business, Váchal’s living dead seem to have found a certain harmony in landscapes minimally disturbed or observed by other people.

Mrtvý v pralese [Dead Man in the Primeval Forest], oil on canvas, 1929.

This theme is paralleled in some of Váchal’s images of dying parts of the Šumava forest, because humans and landscapes are vitally intertwined.

Mrtvý les [Dead Forest] from Šumava, Dying and Romantic (1931). Source.

Folktales

Pohádka [Fairy Tale], oil on canvas, 1914. Source. The mushrooms and the grumpy baby really steal this scene from the other characters.

Some of the motifs in Váchal’s work are recognizable from popular stories, while others seem more like free interpretations of folklore, or records of visions and encounters, like the forest fairies a few images below this.

This Ex Libris seems to be depicting Puss in Boots and a few other classic fairy-tale characters in a novel composition. The man with wild grey hair all the way on the left looks like Váchal himself. Source.

Rodina vodníků [Family of Water Sprites], 1911. Source.

Below: there is one corner of the Portmoneum that never appears in online galleries. Unfortunately, the restorationist is standing right in front of the scene I’d like to show you. It depicts a wild band of the dead swarming on the left, and robbers enjoying a bonfire in a forest glade on the right side. The musuem guides did not specify more about the imagery than saying it was likely based on Czech folk tales. Image source.

Forest Fairies. Source. Here, he is drawing on Czech folklore, but it also seems like the kind of apparition that might appear to any sensitive soul wandering in a beautiful forest on a moonlit night.

As the Saying Goes, the Map is not the Territory

The interpretive keys offered by these intellectual and artistic trends only get you so far. Sometimes, assemblages of motifs are clearly legible, and in other images they aren’t. In the Ex Libris below, the theme—if it is not just a mood created through bricolage—is hard to read:

A pretty intense Ex Libris! Source.

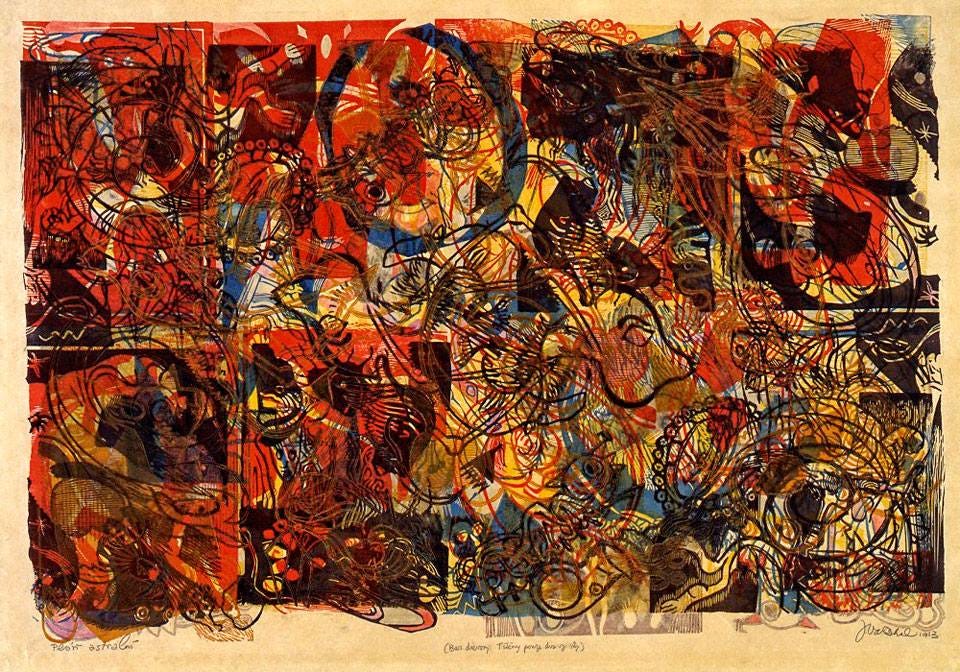

Above: Astrální pláň [The Astral Plane], by Josef Váchal, woodcut, 1913. There’s a lot going on in here!

Penny Dreadfuls and Váchal’s Bloody Novel

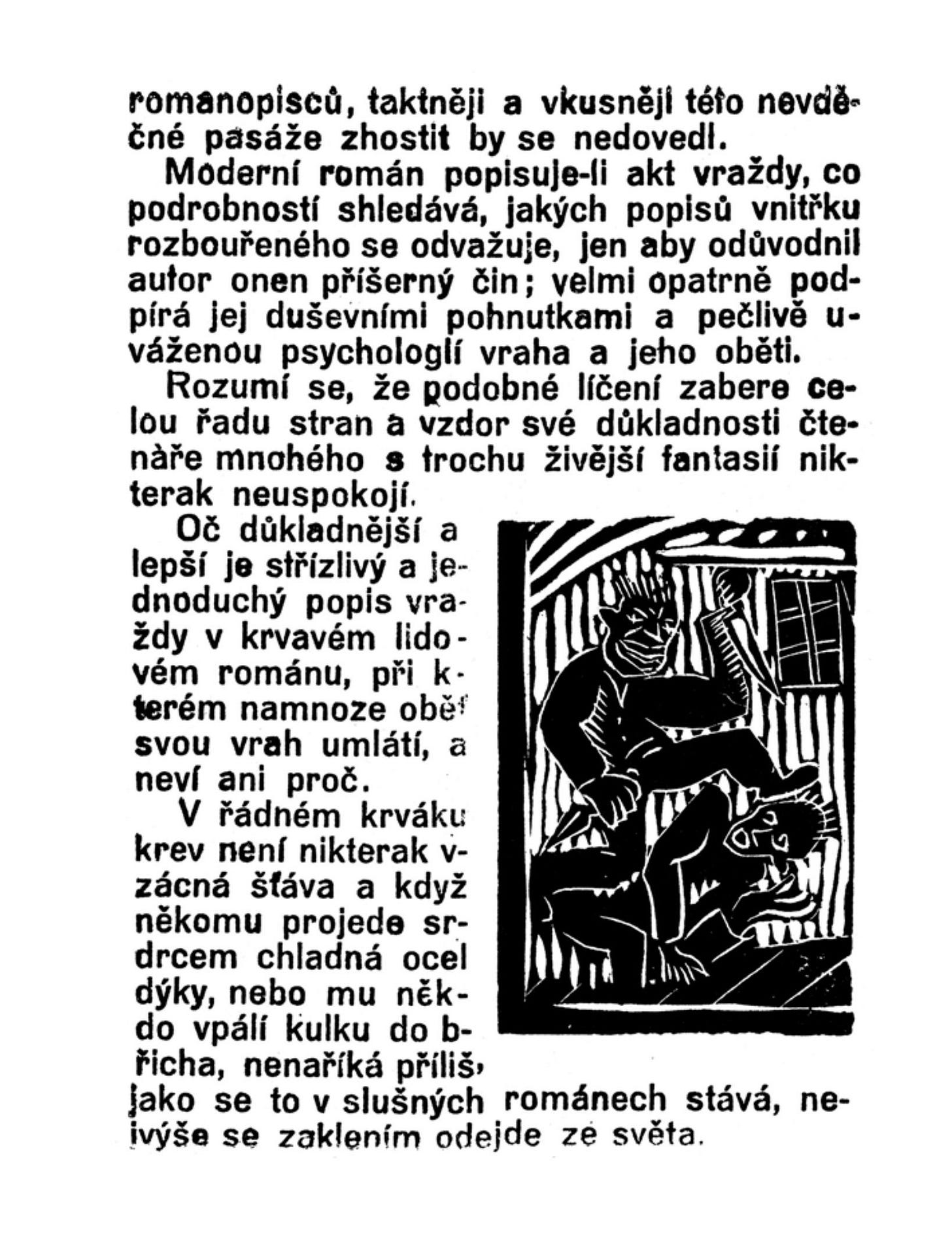

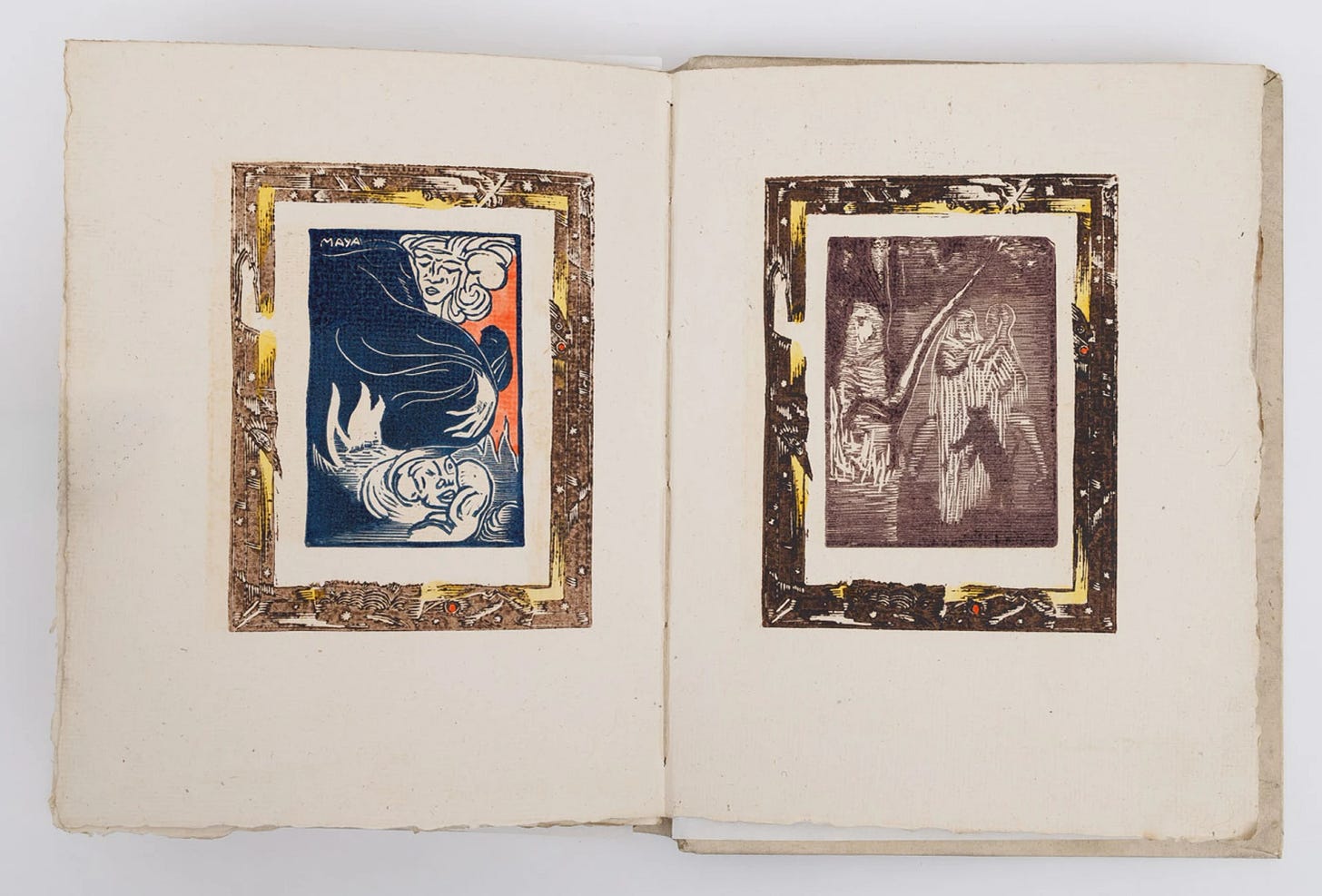

Váchal is perhaps best known in Czechia and in Europe for a work called Krvavý román, usually translated as Bloody Novel in English. It is a perfect example of his holistic artistic approach, as he designed, wrote, illustrated (with 11 old and 68 new woodcuts), typeset, and even bound the volumes himself.

This unique Gesamtkunstwerk incorporates critical, literary, and visual elements, and combines practice of the much-disparaged craft of pulp fiction writing with its impassioned defense. The author’s signature sense of humor shines through in his critical remarks on snobbish literary critics in the prefatory essay, in the comedically grotesque storytelling and illustrations, and in the self-consciously archaic language, deliberate misspellings and typos that gave the flavor of badly edited penny dreadful publications.

Bloody Novel is down-to-earth rather than loftily surreal. It lets readers in on the joke: the joke is on the moralists and censors, who back then, as now, fretted that people would become depraved if they consumed the wrong kinds of media; media which they did not control. The grotesqueness of his exaggerations show how far off the mark the moralists’ concerns are.

One example of his satirical style appears in a section where he describes how pirates prepare their grog: ”The grog was made roughly by adding two teaspoons of rum to three buckets of pure alcohol so the drink wouldn’t be too strong.” (Note to readers: we do this where I come from—Long Island—too, but we call the drink “Iced Tea.”)12

The novel’s chapters teem with sensational events: assaults, revelations, inheritances, battles between Jesuits and Freemasons, madmen, werewolves, and there is mysterious skulduggery galore. Chapters usually end in cliffhangers, which was typical for pulp fiction series that relied on subscriptions.

Yet perhaps the moralists did have something to worry about: no one could read this work and still take the Catholic Church’s pretensions to be a bastion of morality seriously. Just as in the painful and humiliating Counter-Reformation period following the Bohemian Hussites’ defeat at White Mountain, the best defense against overly ambitious clergy was to create legends that showed them in a bad light and to lampoon their puffery and pretensions.

The work is profoundly democratic in its sympathies with the enraptured readers of thrilling adventure tales.

One of the 17 original copies, on display at the Portmoneum.

Unfortunately, there aren’t any full-length English translations of this work on offer, though I was told by a curator at the Portmoneum that one has been commissioned by a publishing house.

Preview pages from Krvavý román from Paseka Publishing House. And here is some Czech commentary lamenting that the work isn't better known today.

Bloody Novel was made into a film in 1993 that has the English title Horror Story. My husband, who is an actor, plays a bit role in it. Here are links to Czech Film Database and IMDb.

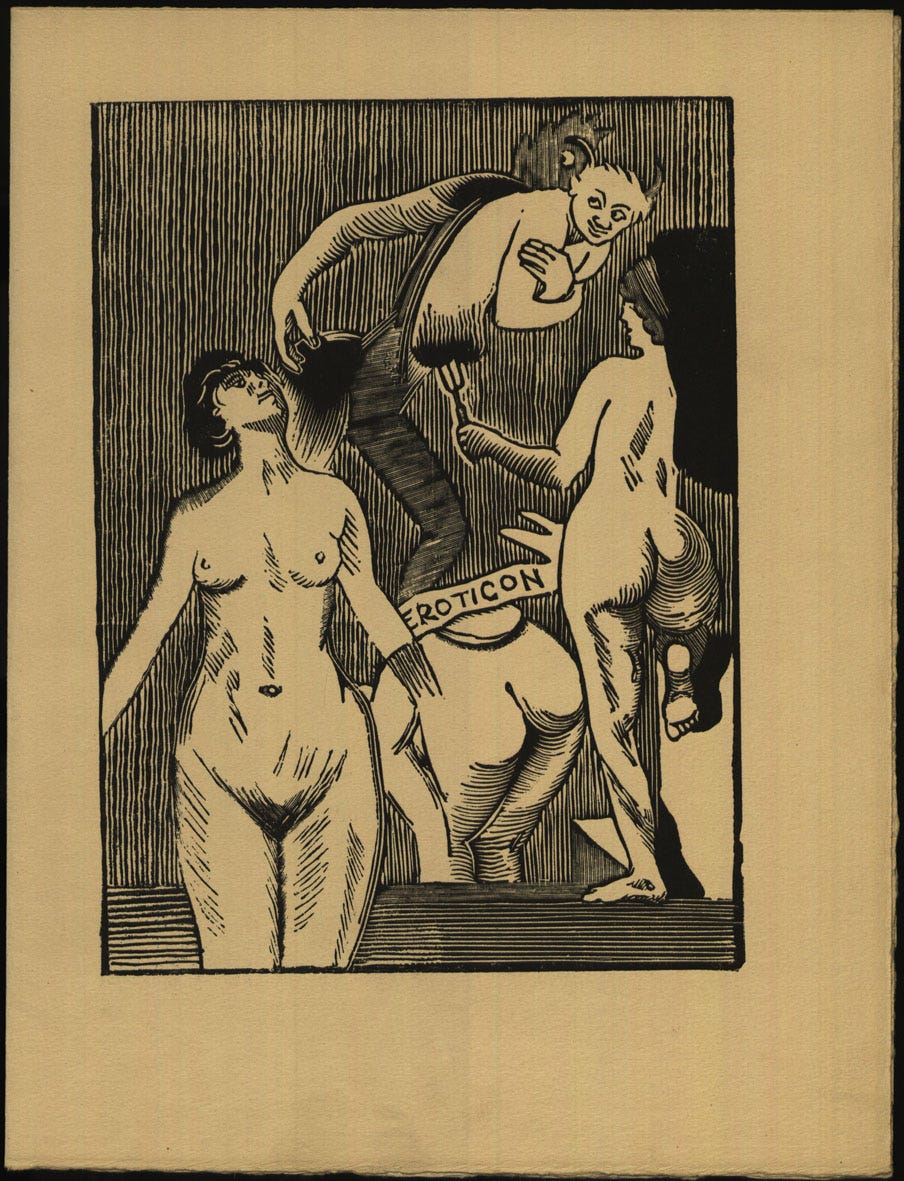

Eroticism

Bear in mind that Váchal began his artistic career under the Austro-Hungarian empire, which made more than token efforts at censoring art and literature that the government, or Catholic authorities were destabilizing or morally corrupt (pornography, political subversion, etc.) The establishment of a democratic Czechoslovak state in 1918 meant clerical censorship was less overt, but was exercised through cooperation with civil authorities. TL;DR: sex was still naughty back then.

Ex Libris made for his friend Josef Portman in 1916.

Váchal had a vital interest in eroticism and enjoyed showing a (figurative) middle finger to authorities through his work, but he was discreet enough to only distribute it through close networks of friends and collectors.

The thematic range of his erotic works ranges from a Futurist machine aesthetic with the brilliance of a sunset (in The Gamekeeper’s Dream) to crude depictions of genitalia, sometimes proliferating like mushrooms after a rain instead of being attached to human bodies. He also wrote essays on the subject, much in the same spirit as his Bloody Novel.

A page from VADEMECUM v erotiky soustech o luze a o buržoustech, ANEBO Krásu zájem, o Lásku, u rozmanitých mamlásků. Source. A vademecum was a kind of handbook. This very limited edition was an eclectic and bibliophilic bonbon that brought together erotic themes and critical poetic reflection with a hearty dose of humor. It pokes at other erotic works of the period, mixing poetry and graphic art with social commentary that explores themes of beauty, love, and human foibles.

An erotic Ex Libris from 1916. Source.

The central female figure in The Gamekeeper’s Dream mural in the Portmoneum (shown below) wears an ecstatic expression similar to St. Theresa. However, what could have been an overbearingly top-heavy, serious scene is lightened by the hunter’s dog, who has been beamed up into the spiritual realm and gazes at her breast, which is either shooting out a ray of light or a stream of milk. The scene to the left is more reminiscent of one of Hieronymous Bosch’s nudist idylls than a gamekeeper’s revir or a Christian or Pagan vision of the afterlife.

I see this painting as both an homage to and a gentle ribbing of the simple country people who are capable of ecstatic flights in their dreams and reveries, while their desires are obscured from them during their wanking hours.

Sen hajného [The Gamekeeper’s Dream]. Oil on canvas, 1920. Source: Portmoneum Facebook Page. The original colors are brilliantly vivid, but all of the images posted on this portal have been tweaked to hyper-saturation.

Detail of Ecstasy of Saint Teresa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The line between religious and sensual ecstasy is thin and perforated even in Catholic hagiographies and art.13

Brána věčně otevřená [The Eternally Open Gate]. ArtBohemia, undated Ex Libris. This image—in my interpretation—suggests that a gateway to new realms is always open through the erotic body.

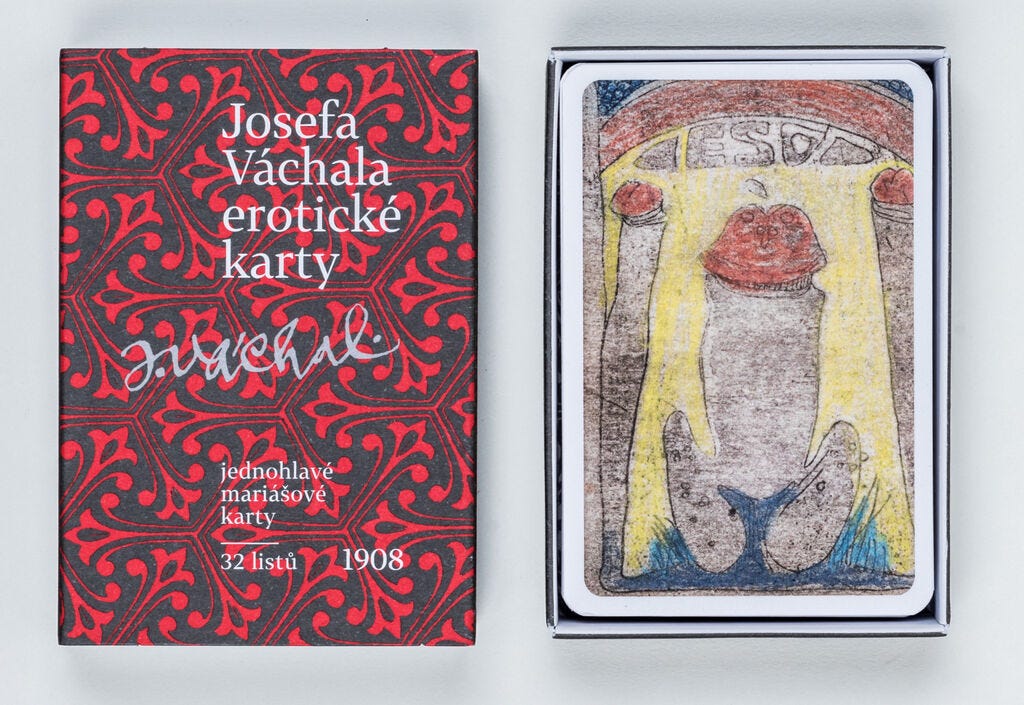

While the circulation of Váchal’s naughty pictures was usually limited to a small circle of collectors, in 1908 he produced a deck of 32 erotic mariáš cards (cards which are otherwise primarily used for playing games and not divination).

No print run numbers are available for the original edition he produced on zinc plates, but their small size meant they could be circulated more easily than framed pictures. And they are still in circulation: a re-issue of the cards was produced in 2024 by the Regional Museum in Litomyšl, accompanied by explanatory texts.

Below: an image of the cards shared on Portmoneum’s Facebook page

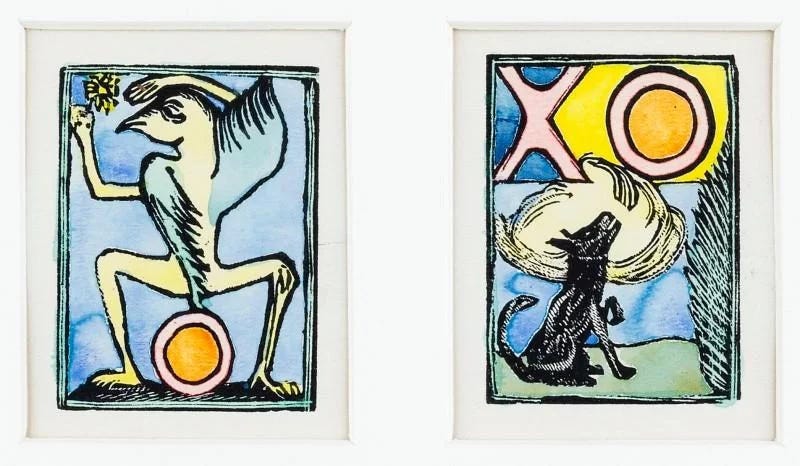

Above: Card images from www.vachal.cz.

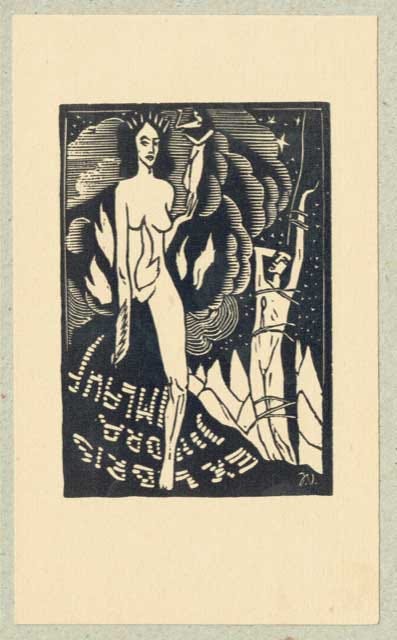

Divination Cards

Four years later—in 1912—Váchal created a set of woodcuts that he used to print his Vykládací mystické karty [Mystical Divination Cards]. Again, there were 32 cards in the pack, and this time they were not based on mariáš symbolism. The images loosely referred to concepts from classical tarot and some Theosophical concepts,14 but they represented his own idiosyncratic visual language and not a true tarot deck.

The cards were intended as prompts for accessing artistic, psychological and spiritual insights rather than as a tool for fortune-telling. While the print run of these cards, like the erotic cards, was small, conceptually, they were a teaching aid that would help users better understand the spirit beings that suffuse our minds and surroundings.

These cards are extremely collectible, and only occasionally turn up in auctions, often framed for collectors to display. I know someone who said he had a deck, but somehow any time I asked he was unable to show it to me for one reason or another.

The cards, of course, are only tinder to light a greater fire. What Váchal was teaching was a way to bypass the rational mind and directly access enhanced ways of knowing, which is so-real rather than surreal.

Vždy umění je sfinga, vždy je život moře

a mezi nimi básník interpret.

On zhloubá jediný ples jich i jejich hoře

a co zbuduje z nich, to jest teprv pravý svět.

Art is always a sphinx, life is always a sea

And the poet an interpreter between them.

He alone fathoms their dance and their sorrow

And what he creates from them, only that is the real world.

Váchal’s verse in Perfect Magic of the Future

Above: several of the cards. Find all of the woodcut images here.

Západ slunce nad Javorem [Sunset over Javor] from Šumava, Dying and Romantic (1931).15 Source.

In Part II on Váchal, I discuss the “hall of mirrors” of European avant-garde art styles, and the goal of Váchal’s lifelong searching.

Don’t miss it—subscribe today, and every post from In the Groves of Symbols will be delivered directly to you.

The Portmoneum is a museum dedicated to Váchal’s work located in the East Bohemian town of Litomyšl. If you click on this link, you will find out a little about the rich culture of the city and its surrounding area (there is a place to click “EN” to read it in English). I will be discussing the Portmoneum in more detail in Part II of this article. For the purposes of this footnote, I’m simply introducing the source of the image.

Some of Váchal’s Ex Libris commissions show Hitler and his minions as figures that emanate a purely evil menace (as well as stupidity, as seen in their facial expressions) as we see in these two Ex Libris prints from 1945. Source.

In my article on the Czech occultist Jiří Arvéd Smíchovský, I illustrate the life of a mage who dabbled in the darkest things (fascism, and also attempts to kill using magic) and had to pay with his own soul, many times over.

Prague's own Faust: Jiří Arvéd Smíchovský

He had an intense and captivating gaze, but, if you were alive at the same time, you needed to beware — he was capable of getting his associates into worlds of trouble. Image source.

In 1940, Váchal moved from Prague to the village of Studeňany, which he referred to as “Tusculum” (exile) as an act of resistance against the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. After the communist putsch in 1948, he was increasingly socially and culturally isolated, and his works—which were unsuited to the new regime’s taste—were rarely seen in public. He lived in obscurity on his partner’s family estate. Even the liberalization period known as the “Prague Spring” in the late 1960s had little impact on his situation.

Source text: “Summary: Josef Váchal, The Magic of Seeking.” I translated this summary of Marie Rakušanová’s Josef Váchal: Magie hledání from Czech into English in 2014.

Specifically, he wrote about colportage (kolportáž in Czech) publications. These were literary works that were carried by traveling peddlers, which people usually acquired through a subscription. They ranged from fictionalized current events (e.g. novels set in recent wars) to Bibles and religious tracts to penny-dreadful novels and adventure stories.

If most people have heard of only one Czech painter, it’s usually Alfons Mucha, and although Mucha was a devout Catholic, he was also strongly influenced by Theosophy. Both of these spiritual streams found their confluence in the artist’s exaltation of female faces and bodies. In his work, anatural elements such as flowering boughs flow together with women’s limbs, hair, adornments and richly ornamented frames.

The conception was not merely decorative: from Theosophy, ”Mucha learned that the world was the creation of Universal Mind, often described as the ‘world soul’. He believed this divine presence to be feminine, and it is represented in his many delightful images of young women embodying health, beauty and pure Nature. Their curvilinear forms express ideal beauty which has the power able to raise humanity to higher spiritual planes.

Mucha observed:

Visible nature, seen through our eyes, surrounds us with rich and harmonious forms. The marvellous poem of the human body, those of animals, and the music of lines and colours emanating from flowers, leaves and fruits are the most obvious teachers of our eyes and taste.”

Illustration from Le Pater, by Alfons Mucha. Source.

”Mucha’s most profound expression of his ‘new age’ spirituality is Le Pater (1899); a book of elaborately illuminated pages depicting The Lord’s Prayer including his own unique interpretation of the text. In Le Pater, God is not a moral force but nourishes the human soul; a more maternal role than is customarily found in Christian belief. Many of Le Pater’s ornate symbols are derived from Freemasonry and Mucha’s own compendium of Art Nouveau motifs based on leaves, flowers and abstract forms. The pictorial element is full of shadowy images of humanity’s struggle to reach the divine, as well as the invisible forces that control human existence.”

Source.

A difference in the philosophy underlying Mucha’s and Váchal’s work is that Mucha perceived one Source-with-a-capital-S that flowed through forms and imprinted them with beauty and harmony, while Váchal perceived a world teeming with intelligences, agency, and personalities that had their own independent existence and did not submit to a higher authority or blueprint.

Mucha and Váchal must have been aware of each other’s work, but I have never read about any personal connections between them.

See "Theosophy and Visual Arts" on Wikipedia.

Membership in occult groups could be a real liability. Ithell Colquhoun, for instance, had been a member of the British Surrealist Group in the 1930s, and was expelled because she insisted on maintaining her association with occult groups, including the Fellowship of Isis and the Ordo Templi Orientis—and this, along with her sex, guaranteed her obscurity for a long time afterward.

Perfect Magic of the Future (1922) was a mystical and heretical manifesto that aimed to define an ideal “mage of the future,” who was a holistic artistic and spiritual personality devoted to imagination, art, love and beauty (rather than arcane dogmas). The balance of microcosm and macrocosm and pursuit of these aesthetic elements elevated the perfect mage above the degenerating banality of everyday life.

Illustration from Perfect Magic of the Future. Source.

The entire Czech title of this book is Dokonalá magie budoucnosti utvořená imaginacemi krásna a lásky, jakož i přetržením tradice starých magií a věr; hlavně proti představě katolického boha a všem imaginacím duchu svobodnému a čistému protivným namířená a bojující (!!!)

But what about the spirits of animals? They are just as ensouled as we are.

A two-page spread from Vigil at the Hour of Terror, Beatification and Prayer for the Dog (1925). Source.

And woe unto those who hurt animals—they don’t deserve anything good. as this vivisectionist is finding out.

Vivisection, woodcut, 1921. Source.

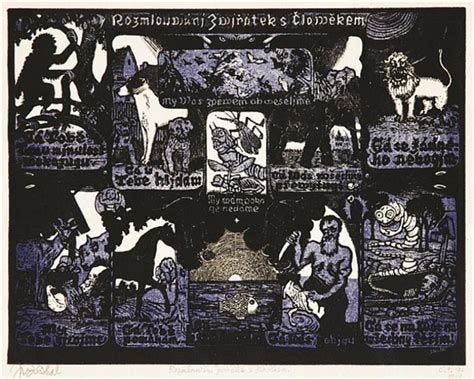

Rozmlowání zwíratek s člowekem [Animals Conversing with Humans], 1914.

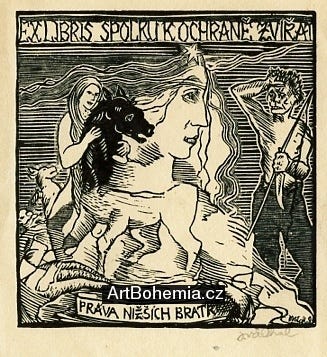

Ex Libris for the Animal Protection Association with the motto “Rights of Lesser Brothers.” Source.

This is clearly related to how he liked to see himself:

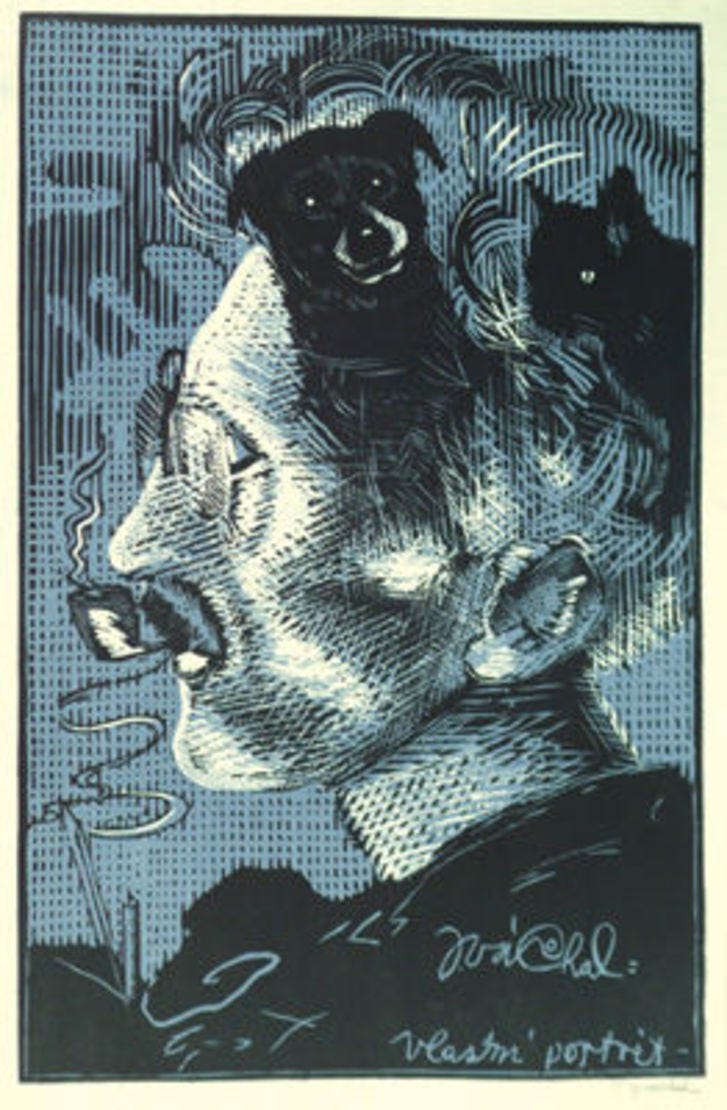

Self-Portrait, undated. Source. The dog looks like his beloved Tarzan,

Ebsco provides a decent overview of the Decadent Movement in the arts for those who want a refresher.

Everyone and their mother can see what’s happening to St. Theresa, but I thought these comments from a Lacanian captured some of how the saint’s ecstasy is transgressive within the order that positioned her as a nun and a saint. Váchal’s heresy, of course, consists in cutting out all the middlemen.

”Jacques Lacan’s reading of St. Teresa of Ávila is one of those moments where psychoanalysis brushes up against the sacred and sets it smoldering. When Lacan gazes at Bernini’s famous sculpture ‘The Ecstasy of St. Teresa’, he doesn’t see only a saint pierced by divine love, he sees a woman overcome by an excess that is both erotic and ineffable. He famously remarks: “You need only go to Rome and look at Bernini’s statue to understand immediately that she’s coming.”

This provocation is more than a joke, it’s a psychoanalytic rupture in the way theology often represses the body. For Lacan, Teresa becomes the embodiment of what he calls feminine jouissance, a surplus pleasure that exceeds the phallic, symbolic order. It’s not simply sexual pleasure. It’s a rapturous, destabilising overflow, a pleasure beyond the pleasure principle, beyond language, beyond the grasp of masculine logic.

Teresa’s mystical writings, filled with fire, longing, and surrender resist easy classification. She describes God entering her like an arrow, a wound of love that brings unbearable sweetness. For Lacan, this isn’t metaphorical. It is real jouissance, an eruption of divine excess in the body. In fact, Teresa’s experience is the very proof that there exists a mode of enjoyment that isn’t mediated by symbolic castration. It is the place where theology meets the Real.

In this frame, the mystic is not merely a holy figure but a kind of radical subject who threatens the symbolic order. Her ecstasy is not submissive but subversive. She does not speak about God, she dissolves in God. She becomes the site of something untranslatable, unspeakable. This is why Lacan says “woman does not exist”, because feminine jouissance is what destabilises the universal, ruptures mastery, and calls into question all totalising systems, even theology.

So perhaps Teresa is not just a saint in a convent cell, but a psychoanalytic rebel, her body trembling at the threshold of the divine, her voice slipping between sighs and silence. She becomes a witness to the fact that there is something of God, perhaps the most real part of God that can only be known through a body, through love, through excess. Something that can never quite be said… only felt. Or maybe, as Lacan might suggest, only enjoyed.” Source: Richard Wiltshire.

In the period between the printing of his erotic cards (1908) and the divination cards (1912), Váchal and several others, including František Bilek, Emil Pacovský, Jan Konůpek, František Kobliha, founded the Sursum group in Prague. This was a short-lived collaboration devoted to spiritual and occult art and often referred to as the second wave of Czech Symbolism.

The group name comes from the Latin motto Sursum corda [Lift up your hearts!] which they borrowed from the Latin Mass. Some members had (heterodox) Catholic faith, but they also visited Masonic lodges and Theosophical organizations, and were involved various other individual and collective projects relating to magic and occultism, as was common among artists and intellectuals at the time.

Sursum’s members met on the first Saturday of each month in Prague’s Café Louvre. Their first group exhibition took place in Brno in 1910, and there was a more successful exhibition at Prague’s Municipal House that attracted more prominent artists and over a thousand visitors.

Sursum’s artists courted controversy, and attracted the attention of censors for nudity and sensuality in their pictures, and for combining religious and mystical themes that didn’t sit well with religious morality-minders.

Ultimately, they lost relevance as Cubism took over as the most avant-garde artistic movement of the time, but Sursum’s two-year existence remains an important historical capsule of a second wave of Czech Symbolism, and the transition from Art Nouveau into Expressionism and other trends. Source.

In some English presentations of Váchal’s Šumava, umírající a romantická, the older Latin term Gabreta is used instead of Šumava for the mountains and the region.

Thanks. I can't wait. All the best to you.

Never heard of him before I am afraid. But the pictures talk a language that intrigues. Thank you for being the interpreter.