Prague's own Faust: Jiří Arvéd Smíchovský

How far would you go to obtain esoteric knowledge? Read about the "Devil of the Lesser Quarter" whose inner shrine was in the library of the Prague university where I used to teach.

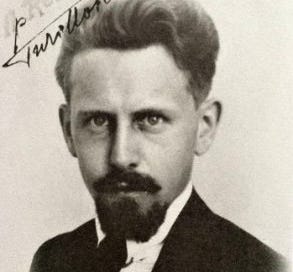

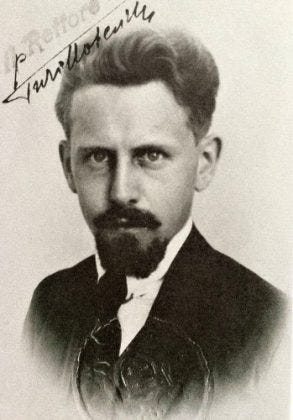

He had an intense and captivating gaze, but, if you were alive at the same time, you needed to beware — he was capable of getting his associates into worlds of trouble. Image source.1

Jiří Arvéd Smíchovský has been known as a Faustian figure, and even as the “Devil of Prague’s Lesser Quarter” because of the lengths he went in pursuit of occult knowledge.

In his heyday, Arvéd, as he liked his friends to call him, was a magnetically charming polyglot and polymath who was blessed with a perfect eidetic memory.

His friend and lover Pravoslav Lexa said:

He was interested in everything, and being endowed with a phenomenal memory, he never forgot what he heard, read, and learned. He had mastered Czech, German, French, Italian, Polish, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. He was at home in the literature of all ages and nations, in philosophy, in political science, religious studies, in medicine, and in the natural sciences, in gastronomy, history, and law. He was known for his unerring quotations, and everyone learned what he needed to know from him. They called him the "walking lexicon” … He tried out formulas for conjuring the devil with the same curiosity as recipes in the kitchen (he was an excellent cook).

Smíchovský’s wide-ranging occult interests included hermeticism, alchemy, kabbalah, and ceremonial magic (raising demons and the devil and making covenants with them), and he was known as a dashing mondain who frequented Prague’s wine bars and had many affairs.

Arvéd’s magical library

I knew a bit about this because between 2012 and 2019 I worked (as an abject adjunct lecturer in anthropology and sociology) at Anglo-American University in Prague. (I was a troublemaker: as Secretary of the AAU Faculty Senate I helped lead a revolt against the administration, advocating for transparency and a living wage for academic workers. This position as liaison between the faculty body and the real decision-makers put me in the hot seat: the administration began persecuting me personally — and I quit before they could fire me.)

Above: this is me in 2018 in the AAU Library.

The university’s campus is split between the Dům u zlaté lodě and the Thurn und Taxis Palace located in Prague’s picturesque Lesser Quarter — a district which has had a reputation for alchemy and other magical activities for the last six hundred years.

Arvéd in his library. Image source. It is said that Smíchovský’s friend, the painter Jiří Wowk, created a portrait of him as a strange beast that devours books. Smíchovský wrote in a letter to a friend that he studies to the point of deathly exhaustion. He spent nearly all his money on books, which — when he was living abroad — he shipped in crates to his personal library in Prague.

In Arvéd’s time, the library contained tens of thousands of volumes, in all the many languages he read, covering subjects ranging from history and political science, to philosophy, theology, natural science, and — of course — magic, alchemy, kabbalah, and hermetic studies.

Above: Dům u zlaté lodě in 2024, bearing AAU’s banners. The building’s name means “The House at the Golden Ship”. Image source: Wikimedia.

Below: the Golden Ship sign up close. Wikimedia.

In 2017, Anglo-American University’s head librarian delivered a fascinating presentation on the history of the library, focusing on Smíchovský and his fate.2 This is how (and where) I first learned about him.

Above: the fireplace in Smíchovský’s library, now the AAU library, as it looks today. Image source. Here is the private sanctuary were Arvéd used to sit and read his occult manuals.

Detail of the Renaissance-era painted ceiling in the AAU library. Image source.

In Arvéd’s time there had also been a curious painted wooden figure of the Devil in the library, which was attested by the researcher Milan Nakonečný3 when he investigated in 1993. The bookshelves were still arranged in a labyrinthine pattern that led to an opening in the center. There, visitors found a small table and a chaise that allowed two people to sit face-to-face in the presence of the menacing sculpture.

In 2022, a film titled Arvéd was released in Czech cinemas and shown at a few festivals. This work falls more into the genre of magical realism than biography, because so much of what Smíchovský experienced was outside of the realm of consensual reality and/or cannot be captured in historical records. Arvéd was directed by Vojtěch Mašek, written by Mašek and Jan Poláček, and produced by Ivan Ostrochovský. Here is the IMDB link. Michal Kern was outstanding in the leading role, depicting the titular character’s descent into madness and oblivion.

Above: Michal Kern in the role of JAS, depicting his enviably louche, scholarly lifestyle. He is about to welcome a lover to his bed. Image source. Kern was awarded the Czech Lion prize for his work in this film.

Selling his soul to all takers

The Czechs say Kolik jazyků umíš, tolikrát jsi člověkem [as many languages as you speak, you are that many times a human being]. If the essence of human beings is their soul, and Arvéd had as many souls as he had languages, he sold at least that many souls to whoever would buy them, and the currency of sale was books.

His intellectual caliber was beyond dispute, but he was driven by several traits that would eventually bring his downfall and destroy his reputation: a drive to self-preservation, all-consuming curiosity, a will to power, and a corresponding lack of scruples (most of the time). This psychological blueprint would bring him into close collaboration with foreign legions, Jesuits, the Italian intelligence service, the Freemasons, Czech and Italian fascists, the Nazi Sicherheitsdienst, and communists pursuing retributive “justice.” (Are you counting? That’s 8, the same number of languages his friend mentioned above.) Smíchovský was occasionally treacherous, sometimes loyal, and mainly committed to growing his knowledge and his library.

The young Arvéd studied at a Catholic gymnázium, and then attended the German university in Prague where he began working on a doctorate in law. However, he was forced to interrupt his studies when the First World War broke out. Smíchovský was drafted to serve as a lieutenant in the Austro-Hungarian forces’ Italian front, where his talents were put to use in the intelligence department. A scholar, not a warrior, he deserted the battlefield and hid in a monastery in Pisa. He was captured and sent to a prison camp. Afterward, he joined the Czechoslovak legions, and also started working for the Italian intelligence service. In later testimonies, he claimed that he did these things to save his skin (for deserters were not treated gently); however, he continued to work for the Italians well into the 1930s when he was no longer in danger of persecution for his desertion.

He pursued further studies abroad, taking a second doctorate in theology at Rome’s Collegium Germanicum, and then a third in philosophy at France’s University of Toulouse.

Arvéd as an intelligence officer during the First World War; photograph from the collection of his sister. Image source. In Italy, he also became a Jesuit.4 Then later, in France, he took up with the Freemasons.

Magical warfare

The use of magic as a supplement to traditional warfare would be a subject for an entire book (or perhaps series of books). In the Second World War, both the Axis and the Allies were employing astrologers and magicians, both in sincere efforts to win the war and in psy-ops, such as when the British intelligence services “leaked” falsely-drawn horoscopes in an effort to influence individuals in the Reich’s high command. Aleister Crowley and others were waging war on behalf of England in both magical and mundane ways, and — no surprise — Czech magicians were at it too.

One of the Czech occultists Smíchovský associated with was the astrologer, hermeticist, and author Jan Kefer.5 Although Kefer’s father was German, he was a patriotic Czech and he organized three rites to curse Hitler (aimed at causing his death) and the Nazis. By contrast, Smíchovský had Czech parents and spoke Czech flawlessly, but his nationality on paper was German. Moreover, like the rest of his patrician family, his connections and loyalties were more international and cosmopolitan, or they were placed with organizations under the umbrella of the international Catholic Church.

Jan Kefer had offered his services as an astrologer to Czechoslovak president Edvard Beneš, but he was rebuffed — they had other plans, the statesman explained.

Kefer argued that Hitler would be vulnerable to magical attack because he believed so strongly in magic and astrology, which would make him easy to target. When it was clear that Beneš and other government functionaries still weren’t interested in his magical contributions to Czechoslovakia’s defense, Kefer freelanced with whoever else would join him.

Surprisingly, despite Kefer’s deadly intentions, Hitler still wanted him to join their team to work for success of the Reich, but Kefer refused. He was imprisoned and died in a concentration camp at the age of 35.

As my Jewish friends say, “may the memory of the righteous be a blessing.”

Above: Jan Kefer (1906-1941) Image: Wikimedia.

Kefer’s grave in the Malvazinky cemetery in Prague. Wikimedia.

Smíchovský was involved in one of the rituals Jan Kefer organized, but apparently, he botched it when he became a little too closely attuned to Abaddon, the spirit of the abyss.6

It was a dark night in early October 1938. The Munich Pact, signed on September 30, had sealed Czechoslovakia’s fate — the Western powers sacrificed it to Hitler in hope of appeasing his ambitions of territorial expansion.

Someone had to do something.

Four men left Prague at twilight, heading out along winding roads that would take them to the side of a picturesque pond in the Brdy Hills. The magicians’ intention was to curse Hitler’s astral body and call up a demon powerful enough to deter him from invading Czechoslovakia; a demon strong enough to harm the Fuhrer’s physical body and, ideally, also kill him.

Kefer had tried to get members of Universalia, the occult society he led in Prague, to join him in trying to raise a national egregore to defend Czechoslovakia, but suddenly everyone had something else they needed to be doing instead. The occultists’ cowardice and lack of conviction in their own magical powers at the moment when they were most needed disappointed him deeply.

But Arvéd and two other men were willing to join. In Arvéd’s case, it was less out of patriotism than out of curiosity — he believed if any magician could raise anything as terrifying — as interesting — as an infernal spirit with this level of power, it was Kefer, and he was along for the ride.

The ritual took place at Dolejší padrťský rybník (“Lower Smithereens Pond”), on a dike between two artificial ponds, where earth, the night sky, and the vigil fire all met. Image source.

The men arrived about thirty minutes before the astrologically auspicious moment Kefer had chosen. The car’s headlights illuminated the site, where the men built a fire, prepared candles, papers with Hebrew inscriptions, and a rich incense composed of dittany, coriander, opium, mandrake, myrrh, heliotrope, hemlock, and peppermint (!)

Then they turned off all their artificial lights.

A man named Gertrüd took care of the magical staff. Kefer did the conjuration, and Arvéd was to guard the magical seal. Arvéd’s lover Alex was tasked with keeping the fire burning and the incense smoking.

Above: the seal of Abaddon.

They censed themselves in the intoxicating smoke and released all non-essential thoughts. Kefer raised his wand, drew a magical circle, and began the incantations. The boundaries of the circle flared up and everything moving within created shadowplays projected onto the quiet forests around them. Time stopped inside the circle while it flowed quickly outside it, as seen in the stars racing along their courses in the black sky.

Kefer sent his intention flying into the astral plane. Something came crunching along the gravel pathway, and the magicians found themselves isolated from the rest of the world. Their personal energies flowed together into one and the air was thick with an uncanny electric power. Thunder growled in the sky.

Arvéd stood unmoving as he focused on Abbadon’s seal, while shadows took on mass and the smoky faces of demons developed distinct features; their helping spirits crouched and prowled around the perimeters of the circle. The magic in the seal transformed its lines into living snakes, who began speaking to Arvéd, luring him into their realm, promising that he was one of their kind and would be welcomed. The spirit of the abyss was now giving him its full attention.

The mage of Malá Strana was overpowered: he found that he could no longer draw a breath. He felt disconnected from Kefer, gesticulating and chanting nearby. And he was afraid for his life. He trod firmly on the seal and the enchantment was broken. He took a step back, and then another until he was outside the magic circle. That was when he realized what he had done: broken the magic, negated the rite. He raised his arms and tried to re-enter the circle, but it would not let him back in. The others were distracted from their roles; they all felt the energies disengage and seep away. Kefer fell on his knees, defeated. He verbally dismissed whatever was left of the demonic presences from the place.

The ride back to Prague was tense. The others were furious and uncomprehending — why had Arvéd broken the rules, banished the magic, killed their chances at success? He was no beginner — so why did he ruin everything? He himself did not know. He apologized humbly because he wanted them to promise never to speak of this debacle.

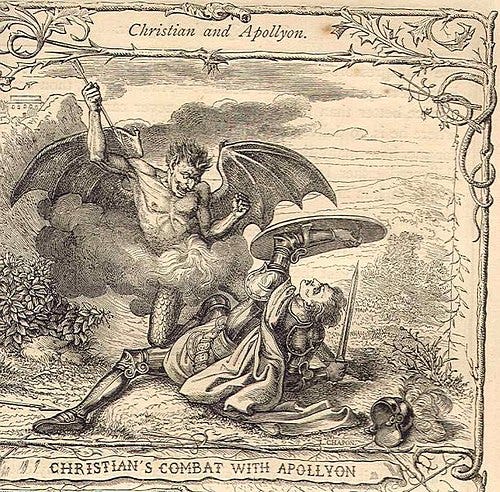

Abaddon (Apollyon in Greek) battling Christian in The Pilgrim’s Progress from this World to That Which is to Come, by John Bunyan. Illustration by H. C. Selous and M. Paolo Priolo, ca. 1850. Wikimedia.

No good deed unpunished

Five months later, Hitler established the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, a nominally self-governed annexed territory which would only be abolished after the Allies’ victory in 1945. During this period, Arvéd helped protect his friend Štěpán Plaček, who was of Jewish origin. Plaček paid him back in books. After the war, when the tables had turned, Plaček extended an arm of protection over Arvéd, which shielded him — at least for a time — from the consequences of his collaboration with the Nazi intelligence services.

Not much later, Plaček would be among the founders of the notorious communist secret police, the StB (Státní bezpečnost), who began terrorizing some of the same people who had also been victims of Nazi oppression. However, Štěpán Plaček was among the first purged by the Communist Party when it began to mistrust and liquidate its own people during the Stalinist Terror.

Above: Štěpán Plaček. Image source.

Besides Plaček, Smíchovský also protected a number of other Jews (whose names are unknown), saving them from deportation to concentration camps and certain death. He did this by arranging their assignments in the Archives of Prague’s Jewish Museum.

Smíchovský as a fascist and Nazi collaborator

First, it has to be stated that Smíchovský was in a precarious position under the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. As a well-known homosexual, he was very easy to blackmail and to squeeze for information, which he would willingly provide a) to keep himself out of trouble, and b) in exchange for other favors the Nazis might offer (such as rare books).

However, despite making exceptions for Jewish friends such as Plaček, it cannot be denied that Smíchovský really did have fascist sympathies.

Picture of the Vlajka flag. Image source. Vlajka (which means “flag”) was a Czech fascist movement active before and during the Second World War.7

Smíchovský was also a very close friend (and lover?) of the fascist officer Radola Gajda, leader of the National Fascist League — a movement based on Benito Mussolini’s Italian fascism. (Remember Smíchovský’s Italian connections from a previous chapter of his life?) The National Fascist League was active in the interwar period and during WWII, and was responsible for the only fascist coup in Czechoslovak history (thwarted by regular troops assisted by gendarmes in Brno). The National Fascist League opposed Jews, communists, and the Czechoslovak government.

The Nazis did not support this movement because its leaders had been critical of Hitler, and the Sicherheitsdienst (secret police) approached Smíchovský, asking him to track General Radola’s movements. Arvéd, a loyal friend, told Radola that he had been assigned to spy on him, and when the latter was tried and condemned after the war’s end for his fascist activities, this was the only case when Smíchovský refused to provide any testimony.

Above: Radola Gajda. Image source.

The National Fascist League’s emblem. Image source.

Smíchovský was deeply interested in Jewish magical lore, but he did not care much about what happened to the Jewish population (other than his personal friends). In fact, if something terrible happened to them and he had a chance to get their books, he took the opportunity.

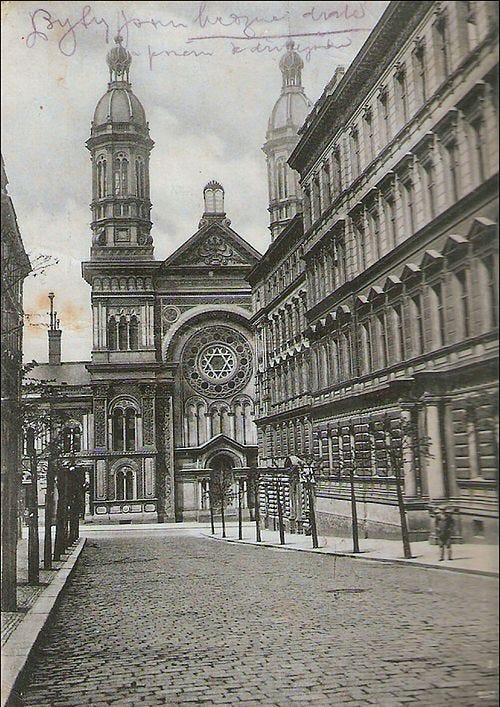

The Vinohrady synagogue in a 1910 postcard. Image source: Wikimedia.

He even headed a fascist militia that attacked the synagogue in Vinohrady. As the police report mentions, his motive was probably looting rare volumes from the house of worship. Arvéd was also enthusiastically collecting books confiscated from Jews during the Czech holocaust.

Out of the frying pan into the fire

At the end of the war, Smíchovský was set free from the Nazi-run Pankrác prison. But he was again in a very precarious position. Not only as the scion of a bourgeois family, but as a well-documented Nazi collaborator. Days after his release, he was arrested by Czechs and forced to give testimony in a number of trials, both against true collaborators and against other people who were inconvenient for the communists in one way or another.

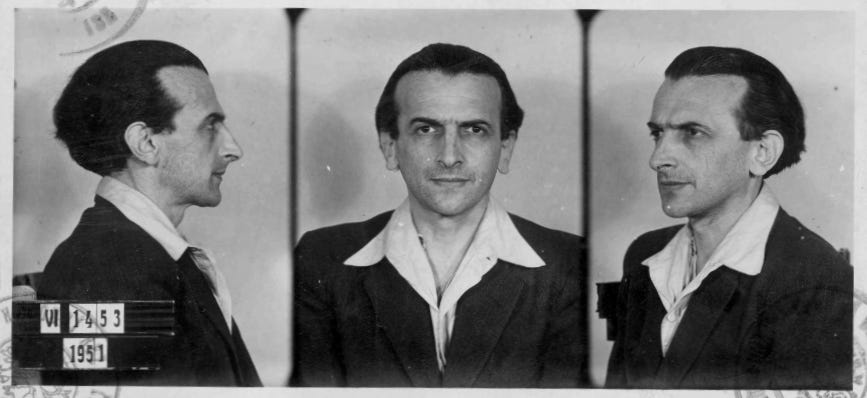

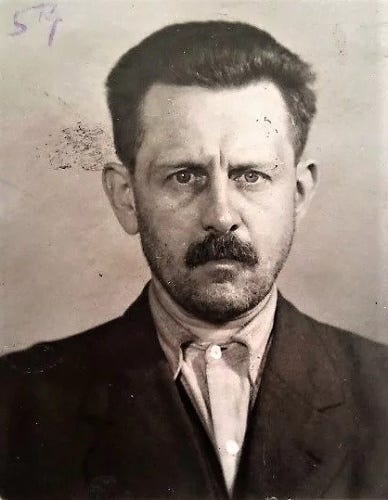

Picture from Smíchovský’s communist secret police personnel file. Image source.

Smíchovský claimed that his testimonies were responsible for sending 49 people for execution. On the other hand, he also said that he rescued several dozen others.

Above: Mírov prison. Image source. He would be in and out of this prison, and several others, from the end of the war until the end of his life, in 1951.

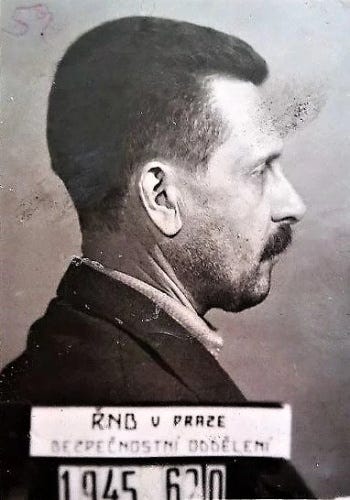

A prison photograph taken in 1945. Wikimedia.

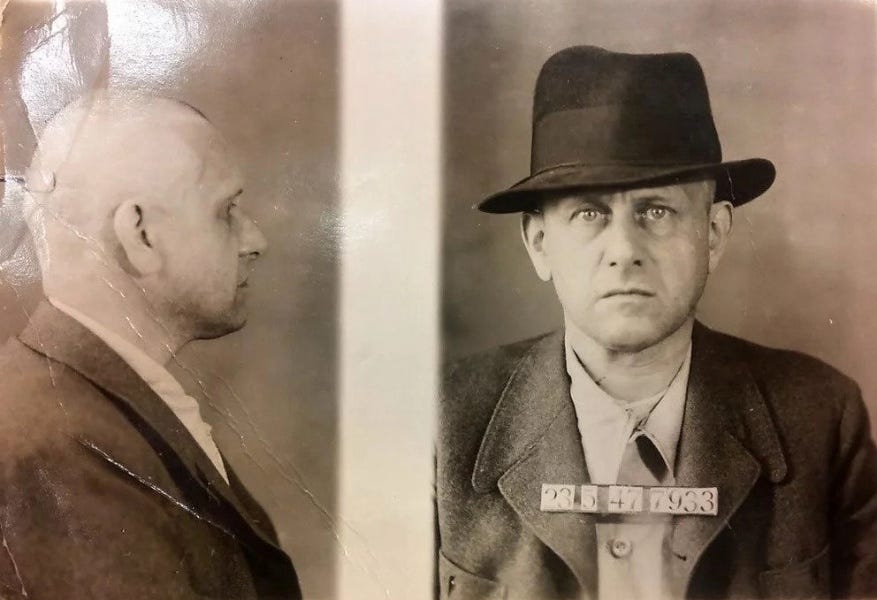

Mug shots from 1947 where he is still wearing his street clothes. Image source.

Things continued to get worse for the mage … his testimonies were wanted by the new communist elite, but low-level functionaries and guards saw him as an ordinary quisling and they treated him roughly. His status fell, and he spent longer and longer stints in prison, where he had to beg for small favors: books, cigarettes, a visit to his sister in Prague. The more he testified against people, the fewer friends he had left. What about diabolical helpers? He threw himself into frenzies of chanting and ritual.

The guards at the Mírov prison considered Smíchovský a madman. His once-ornate rites stripped back to only mind, voice, and perhaps chalk signs on the cell floor were frightening enough to witness, but prison personnel also recorded that he performed a circumcision on himself. A Dominican monk who had spent some time as Smíchovký’s cellmate reported that the magician used an old Greek text in a ritual in which he tried to conjure the Devil so he could be carried away.

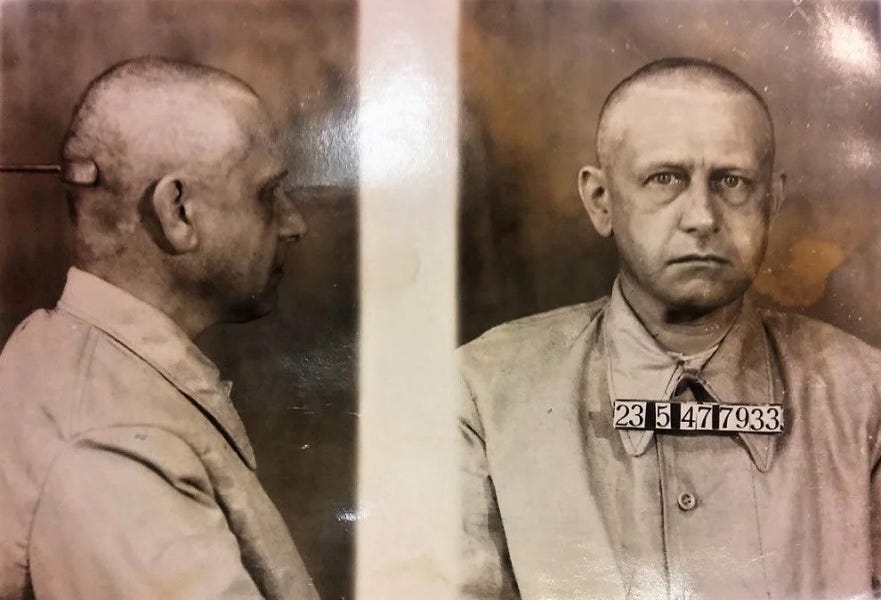

Above: Smíchovský looking more haggard, now wearing a prison uniform. Image source.

He called upon the most potent allies to attend him in his abject state in this terrible place. He had felt the shadows of a great power during the rite at Dolejší padrťský rybník. He repented of his mistakes and was desperate to make himself worthy of relationships with these spirits — couldn’t they deign to do something about the mundane and deadly dangers that were drawing almost as tight as a noose around his neck? How many more signs of commitment, of mastery, of focus did they still demand of him?

Arvéd knew well that he would only be useful to the communist apparatus of state terror, which used him to send others to their doom — until they decided he wasn’t, and that was when he would meet his own.

Jiří Arvéd Smíchovský’s trial was one of the last in the series of prosecutions of people accused of treason and collaborating with the Nazis. The communist prosecutors saved him till the end because he was wanted as a witness in so many previous trials. Many of the men he testified against had not been fascist collaborators, but high-ranking officers of the Czechoslovak Army who were sentenced on made-up charges in order to discredit the Czechoslovak resistance movement. (This was at the behest of the Czech and Soviet communists in order to elevate the role of Soviet-led liberating forces.)

At the time of Smíchovský’s trial, there was a massive press campaign against him, which portrayed him as the “murderer of Malá Strana” and “the Devil’s friend.” Among the accusations leveled at him during the trial, prosecutors claimed he was a “secret Jesuit” and a Freemason: neither of these associations were in good odour in the communist judiciary.

Thanks in part to his self-led legal defense (for he did hold a doctorate in law), he was able to get his death sentence commuted to life imprisonment, and, because he had German citizenship, his friend Štěpán Plaček tried to arrange for Arvéd to be transferred to East Germany. However, Plaček’s position was slipping, Arvéd’s rituals were not working, and this would never happen.

On January 22, 1951, a prison guard struck him on the back of the head with a heavy object. He was taken to the infirmary, and that evening he died of the aftereffects of this assault. His corpse, they say, was an unsettling shade of black. (As if in contrast to the old legends about saints with perfectly preserved or sublime bodies of light, and even in contrast to the initials of his name: J.A.S. The word jas, in Czech, means “brilliance,” “splendor,” and “illumination.”)

The other prisoners were relieved to hear of his death, because they were furious at his denunciations of others and terrified that they would be next to face him as a witness in a show trial.

His body was deposited in a mass grave on the premises of Mírov prison. Many years later, a park was built there, and all the bodies were moved to another mass grave site. The Smíchovský family’s elegant tombstone does have his name inscribed on it, but the whereabouts of Arvéd’s remains are unknown.

Arvéd’s Legacy

It isn’t possible to wrap Jiří Arvéd Smíchovský’s legacy into a neat package. He was too intelligent and arrogant to be considered a naive victim of circumstances. One might pity him for having been used by the Nazis and communists, and he showed character when he took risks to save friends and acquaintances. Yet, he also willingly participated in fascist activities, with motivations ranging from sympathy with their aims to his all-consuming passion for collecting books to having been blackmailed because of his sexual orientation.

Some members of the Czech occult community accused him of betraying their fellows to the Sicherheitsdienst, but this was unfair: he had protected the occultists in his circles. He was even accused by rivals of having sicced the authorities on Jan Kefer, which he vehemently denied.

Another perspective on Smíchovský’s collaboration is that his work as a librarian and archivist in the service of the Protectorate made rare books available to more readers in libraries. And it cannot be overlooked that while he was employed by the Nazi secret police he engaged in willful obstruction of their activities, for which he was repeatedly disciplined, and even imprisoned. Protectorate records document what a terrible employee he was: his misconduct included thwarting their investigations, concealing material from his superiors, and making various other “unauthorized interventions.”

There are two ways to look at this: one is that perhaps, underneath it all he had a moral sense that the Nazi regime was illegitimate and he did not support it. However, on the other hand, he was also canny enough to see that the war was ending, and he correctly calculated that if he were in a prison he would probably be set free and pardoned. And this is exactly what happened: when the Nazi-operated Pankrác prison was liberated at the war’s end, he got to walk free (until the communists arrested him). Teasing out to what extent he acted on scruples or out of self-interest is impossible.

Arvéd was a theologian who became a Satanist; a bon vivant and a bookworm; an aristocratic victim of the dictatorship of the proletariat; a show trial witness who got what he “deserved”; and an angel of mercy and of death in the courtrooms. His life was a Gesamtkunstwerk in the deepest, truest sense of uniting a variety of artistic and intellectual forms, which necessarily bears within it the roots of tragedy.

At Anglo-American University, Smíchovský still has a terrifying legacy:

I have heard several stories of librarians who work in his former occult chamber who have been driven “mad” — they received diagnoses of mental illness and/or were hospitalized for it. Naturally, I cannot provide further details about these cases, but a belief persists that his baleful influence — or something even deeper and darker — still haunts the subterranean chambers beneath the library.

In this old Renaissance building, which had been constructed on a former funeral ground, as evidenced by the discovery of human bones during its reconstruction, the specter of a man appeared; something all too diabolical was dwelling in the house. Whoever succumbs to its metallic, challenging voice and the imperative gaze of its red eyes shining in the darkness must descend to the very nadir of his own being. Source.

Mephistopheles über Wittenberg. Lithograph to illustrate Goethe’s Faust, by Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix, 1828. Wikimedia.

In researching this article, I have drawn on oral history and lore from Anglo-American University; a presentation made by its head librarian; the film Arvéd, for inspiration; the book Malostranský ďábel by Jan Poláček (which the film was based on); this excellent article hosted Okultura.cz; and various other online sources. The first image in this article, which is also its thumbnail, was taken during Smíchovský’s doctoral studies.

There is, unfortunately, very little available about Smíchovský in English. I think part of the reason for this is that it isn’t possible to sympathize with him, even though a few of his traits or behaviors were likeable or intriguing. We certainly can’t hold him up as a martyred occult saint, even though here and there his actions were virtuous. Nor we can fully condemn him without qualifications, since he was forced by historical forces far beyond his control to obey orders or else perish. (His friend Jan Kefer made the latter choice.)

I asked her several times since then if she’d be willing to do a reprise of the presentation at another venue, such as at a literary festival, and she refused every time. At first, she gave practical reasons for not wanting to engage with this extra work, but later she flatly told me to stop making these requests: “Smíchovský is evil! I don’t want to engage with him any more.” So I stopped bothering her about it.

Look, the librarians are not wrong about his involvement with dark powers, whether you take that from the demonological side or from the perspective of 20th century history. Smíchovský was put into binds and forced to make compromises that none of us would want to face and few would handle with perfect moral integrity, but he also made some choices that showed a lack of integrity.

Please do not inquire about Smíchovský at the library — it will irritate the good people who work there, and you will not find out anything new. And, if you speak my name to anyone in the university’s higher administration, you’ll probably get defenestrated.

Thank you for understanding !!!

If you want to find out more about Smíchovský, I suggest translating materials from Czech (and other languages, such as French, Italian, and German) using whatever means you have available.

His article was originally published in Revue HORUS, Solstitium 1993, and has been republished by Okultura.cz here.

Note: the Jesuits were connected with Mussolini and his Italian fascism, for example through the intermediary figure of Pietro Tacchi Venturi. Pope Pius XII who was in office during the war was almost certainly anti-Semitic and deliberately ignored the Holocaust.

There is a Czech Wikipedia page on Kefer that provides a very basic overview. This English page is even more abbreviated and is flagged for not meeting Wikipedia’s standards in several areas. Kefer’s publications and works written about them are available in Czech.

This description of what happened during the ritual was translated and adapted from Jan Poláček’s Malostranský ďábel, pp. 134-150.

Notes summarized from here:

The leader of this fringe-right movement was Jan (Josef) Rys-Rozsévac. The group had its own newspaper, whose title Árijský boj (“Aryan Struggle”) gives some idea of their ideology. After the German occupation Vlajka struggled with the Protectorate government for for a “place under the German sun," but they did not gain approval by the Reich nor were they supported by more than a handful of Czechs.

In the beginning of 1940s, Vlajka merged with Český národne socialistický tábor (Czech National Socialist Camp), and their symbol was the so-called “Rune Cross,” which was a sign unrelated either to actual runes or the Christian cross.

The Dream of Faust, by August von Kreling, 1874. Wikimedia.

Great piece, Melinda!!

I'm Czech, even though a long time expat, and never knew this fascinating piece of my country's occult history, thank you so much for sharing it with us!!!