Speak of the Devil! Lupus in Fabula!

(We don't talk about Bruin — no no no ... ) Noa-names and superstitions about summoning wolves, bears, and devils

Lupus in fabula!

Painting by Tokyo-based "naive" artist Kosuke Ajiro

Lupus in fabula means “the wolf in the story" in Latin. It was taken from Terence's play Adelphoe1 and can be interpreted in context as "if you speak of the wolf, he appears.” It’s similar to the way that in English someone else is bound to appear if you speak of him:

The Devil in the Marseilles tarot deck: hermaphroditic, bestial, and dressed to party. Take a look here for an analysis of Devil card imagery in the tarot.

Who’s afraid of the big, bad wolf?

Language encodes commonly-shared ideas about things, and in the case of wolf terms, it usually reflects a negative attitude toward whatever people are referring to as wolfish. Only fairly recently have there been efforts at rehabilitating wolves, based on a better understanding of their ecological role.

For example, in Czech (a language I speak every day), when someone gets hemorrhoids or other sores in their nether regions they call it “catching a wolf” [chytit vlka]. It must be said that this is unfair to wolves — and probably based on poor or absent observations. In the rare events when wolves attack humans, they bite the extremities and sides of the torso rather than the booty hole or groin, in keeping with their fighting style (they often attack rival wolves’ extremities) and their hunting style (attacking shoulders and flanks). The autoimmune condition called lupus also bears the Latin name for the wolf, probably thanks to the thirteenth-century physician Rogerius who thought patients’ skin lesions resembled wolf bites.2

“Wolf tones” occur when someone playing an instrument, particularly a bowed stringed instrument, creates a certain “impure” pitch with unpleasant overtones or distortion. It is very hard for players to control wolf tones, and they cause chagrin to musicians and their audiences alike. Wolf tones can be similar in sound to the “wolf fifth” (also called a Procrustean fifth or imperfect fifth); a very dissonant musical interval that spans seven semitones. It was produced by a tuning system that was popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Wolf trees are not a particular species, but may be any kind of forest tree that has broad girth and great, spreading branches. They are usually surrounded by smaller trees of different species. Wolf trees are often over 150 years old, and usually achieved their impressive shape and size because at one time they were the only tree allowed to grow in a pasture or other cleared area. They are called “wolf” in reference to what was considered their undesirable growth habits. In the nineteenth century, foresters characterized them as “avaricious flora … a side-crowned perennial, towering over and shading out the other trees of the forest. More generally, it is any member of a sylvan aggregation that takes up space which the Maker has ostensibly allotted to one or more of the vigorous, valuable individuals in the forest.” Eliminating these “forest ulcers” was a rule for rational forest management, just like eliminating wolves was a principle in wildlife management, and eliminating (and then assimilating) Indigenous populations was a national policy.3

A wolf tree

Undesirable branches on fruit trees that are called water sprouts or “suckers” in English are called “wolves” in Czech.

Another Czech expression is “wolf claws” [vlčí drápy] for a dog’s dewclaws: vestigial digits found on its legs, higher than its foot, which do not bear weight when the animal is standing. This is another unfair association, since wolves and other wild canids lack dewclaws on their rear legs. I’m sure you’re starting to see a pattern here …

More amusingly, Lycoperdon, the genus of about 50 puffball mushrooms takes its name from the Greek words for “wolf” and “fart,” an association that holds true in other languages (in Spanish Pedo de lobo or Cuesco de lobo, and in French it’s Vesse de loup).

The flatulent names for puffball mushrooms are inspired by the dark cloud made by its spores when it propagates itself.

Gardeners know that the botanical name for tomatoes is Solanum lycopersicum — the "comforting wolf peach." But what do wolves have to do with tomatoes? Well, at first it reflected a general sense among Europeans that this member of the nightshade family was just as poisonous as its relatives nightshade, henbane, and mandrake, and then, more specifically, German legends which said that witches and sorcerers put tomatoes into potions that turned them into werewolves. (Again, probably a result of confusion between the tomato and more psychoactive members of the Solanaceae family)4

Image by Hanna Kolmiokissa at drawception.com

The wolf’s negative reputation is also familiar to us from fables and folk tales, such as Little Red Riding Hood and Aesop’s fable about the boy who cried wolf. These stories rely upon the same essential concept of the wolf as the “wolf in sheep’s clothing” spoken of in the Gospel of Matthew (and not in one of Aesop’s fables, as is widely believed). The author of the text attributed to Matthew was warning against false prophets who look innocent but are dangerous to those who follow them, and he follows his lupophobic statement with some a couple of botanically-confused metaphors.

Then in Acts 20:29, Jesus warns his followers: “For I know this, that after my departing shall grievous wolves enter in among you, not sparing the flock.” Like the expressions “keeping the wolf from the door,” or “throwing someone to the wolves,” these references assume that people listening to the stories believe that wolves are dangerous and cunning, and coming after you.

A person considered wolflike may also lack manners, morals, or respect for others: “wolfing down” a meal means gobbling it without regard for mealtime conventions. A wolf whistle is a signal of sexually predatory thoughts or intentions which aims not only at making these evident, but also at dominating public space. Extending the metaphor a little further from any form of animal behavior, Jordan Belfort, the main character in The Wolf of Wall Street, was an economic predator who greedily, selfishly pursued his own interests at the expense of others.

This wolf painted by an unknown medieval artist is demonstrating how little it cares about human social conventions. I don’t know why his feet look so strange — they almost resemble cloven hooves, or even bat wings.

A somewhat more positive connotation is found in the Czech folk botanical name “wolf poppies” [vlčí mák] for the wild red poppies that spring up around fields. Like “wolf shoots” on fruit trees, wolf poppies also aren’t of any use to the farmer, but people often find them beautiful. The other kind of poppies (legally) grown here are mák setý, the breadseed poppy sown by farmers who harvest its seeds for use in baking.

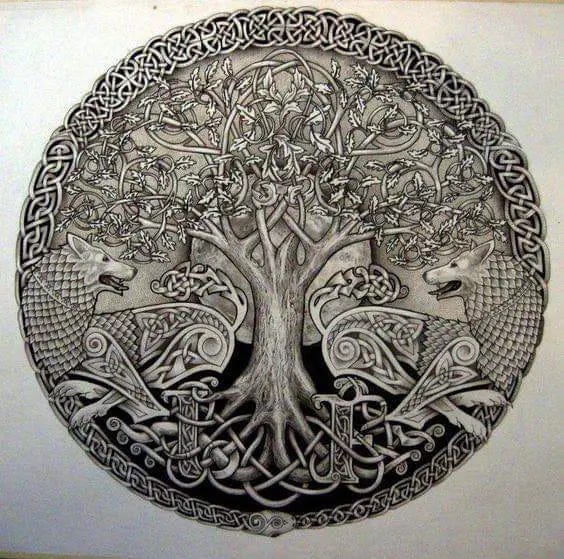

Tattoo by the artist Any for a client of Hell (a tattoo salon) in Prague. Shared on the salon’s Facebook page.

Not speaking of the Devil — noa names

The Czech equivalent of “Speak of the devil (and the devil appears)” is “My o vlku a vlk za dveřmi [We (speak) of the wolf and he’s right by the door]. However, it no longer reflects a living superstition about wolves; rather, just like the English expression, it’s used in situations where someone’s name was just mentioned and they suddenly and unexpectedly appear.5

Today, “speak of the devil” is used in a lighthearted, joking context, but prior to the 20th century both the devil and speaking about him were taken much more seriously. The phrase first appeared in Giovanni Torriano’s Piazza Universale in 1666: “The English say, Talk of the Devil, and he’s presently at your elbow.” In efforts to avoid accidentally conjuring up this frightful being, many euphemisms were used, such as Prince of Darkness, Old Nick, or Old Scratch.

An illustration from the 13th-century Czech Codex Gigas, a.k.a “The Devil’s Bible”.6 Note the non-weight-bearing dew claws on his feet! The color of his face is also significant: blue and green were typical in representations of the devil and demons from late antiquity through early medieval period blue, in a continuation of the classical association of blue with the underworld, death, and barbarism.

In some traditions, gods or spirits are pleased when they overhear humans speaking about them — so long as the humans use flattering names. For example, the ancient Greeks referred to the Erinyes (i.e., the Furies, chthonic spirits of vengeance and retribution) as the Eumenides (“benevolent ones”).

The contemporary artist vee209 created this image titled “Furies: Study No. 1” based on Aeschylus’ Oresteia.

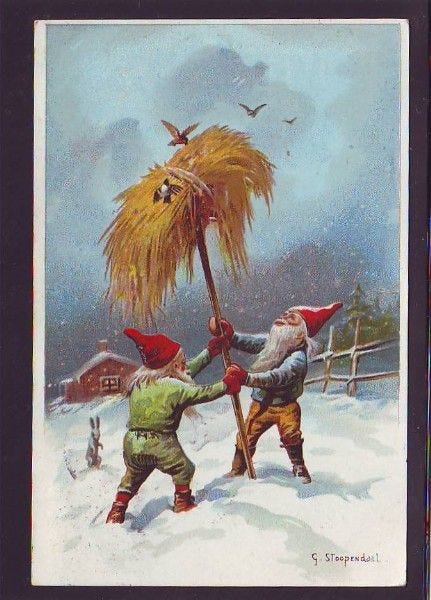

Fairies are referred to in some countries as the “Good Neighbors,” and one of the names given to a household spirit of the type called tomte7 in Sweden is nisse in Denmark. Nisse may be derived from the Old Norse word niðsi, meaning “dear little relatives,” which would help the spirits feel welcome in the home and perhaps even put them in the mood to help instead of causing mischief.

A vintage Danish postcard depicting two nisser erecting the last sheaf of grain to offer the birds at midwinter. I discuss this tradition in my article about the Corn Wolf.

These polite names are not quite the same thing as a euphemism. Everyone is familiar with those: expressions that are considered more acceptable by sensitive members of the speech community, sometimes used on behalf of others that the speaker or writer wishes to protect (e.g., children, or those who are grieving). For example, “pass away” is often used in place of “die”; “doing it/doing the deed” may be used instead of “sex”; “number one” and “number two” have come to represent functions most commonly described in informal English as peeing and pooping; “bathroom” or “restroom” is used instead of “toilet”; and one even hears “lady dog” used instead of “bitch.” Some euphemisms are absurd if you attempt to parse their literal meanings, such as: “The dog went to the bathroom on the sidewalk,” but they are conventionalized to such a degree that people still understand what is meant.

Euphemisms both mask and draw attention to the words they replace, while also functioning as a kind of virtue signaling for the speaker, who is tacitly communicating: “I know the other word, but I’m choosing not to use it.” Occasionally, euphemisms may draw attention to the speaker’s intention to elude censorship or display wit, as when people use the word “unalive” to escape repressive algorithms, and when Shakespeare referred to making the “beast with two backs” in Othello.

The alternate names assigned to the Devil also were neither flattery nor euphemisms: they are what linguists now refer to as noa-names or apotropaic8 deformations that stand in for a tabooed word. The use of noa-names arises out of the fear that speaking the true name out loud will summon the thing, which is not the case with euphemisms. The term and concept were borrowed from the Polynesian noa, which is the opposite of a tapu (taboo). A noa is a kind of blessing that has the virtue of lifting a tapu from someone or something and thus preventing bad luck.9

Noa names for animals

Fierce animals have also been assigned noa names / apotropaic cryptonyms, out of fear that saying their true name would summon them. But finding out about things people weren’t allowed to say in a period when nothing was written is a great challenge.

Scholars in the 19th century began reconstructing an unwritten ancestral language that they named Proto-Indo-European (PIE). This language was probably spoken as a single tongue between the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age, perhaps until 2500 BCE (though estimates vary). Recent research indicates that the Proto-Indo-European tongue’s homeland was in the eastern Mediterranean around 8000 years ago. Over time, the original PIE diversified into the families of Indo-European proto-languages and then further developed into many of the languages still spoken today, which range from Welsh to Greek to Lithuanian to Farsi.

Linguists use deductive methods to trace the evolution of words’ sounds and structures to make informed guesses about how their meanings have changed.

It is interesting that one of the words from PIE that has been lost to most of the Indo-European languages that developed out of it is the original term for bears.

This image is sold on t-shirts by Grizzlygifts on RedBubble. It’s not exactly focused on zoological terms, but was the only bear word cloud I could find.

Unbearable risk

Geography played a role in determining where this happened, and where it didn’t. Bears are more often found — and are probably more feared — in northern than in southern lands, which may be the reason southern Indo-European tongues kept their PIE-derived words for bear, while taboo-avoiding terms were substituted for it in the northern languages: the Germanic (which includes English, German, Dutch, and Swedish), Slavic (which includes Russian, Polish, and Czech), and Baltic (Lithuanian, Latvian, Old Prussian, etc.) language families.

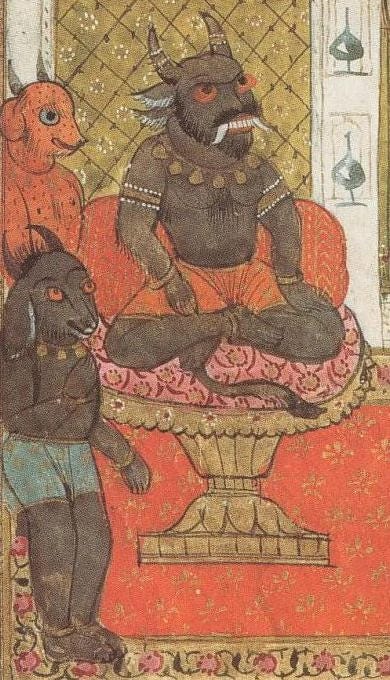

The original PIE word for bear may have been h₂ŕ̥tḱos or *rkso-,10 which scholars have deduced means “destroyer” based on its similarity to rakshas and rkshas, Sanskrit cognate words that mean harm or injury and bear, respectively, and rákṣasa, which refers to supernatural, shapeshifting demons in Indian myths that are usually taunting and malevolent.

Check out this article for a nice gallery and discussion of rákṣasas.

It is not known if the original guttural PIE word was itself an apotropaic cryptonym that hid an even more fearsome earlier name for the animal. No one wanted to summon them — people already lived in fear that they would just show up unexpectedly and cause havoc, as you can see in this gallery of medieval illuminations.

One of the illustrations from the gallery cited above: this maiden was apparently abandoned by her knight in shining armor. And other illustrations indicate that even unicorns weren’t safe from bears!

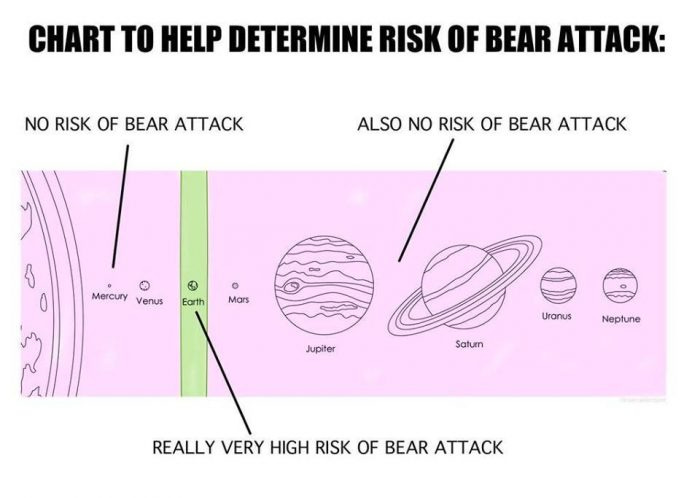

Really, who is safe from them? While a wolf is unlikely to actually show up at your door, bears sometimes invite themselves in — and even help themselves to your porridge.

This map only illustrates proximate risk. More detailed data are needed to determine the risk of bear attacks in your area. Don’t open doors unless you know who’s knocking.

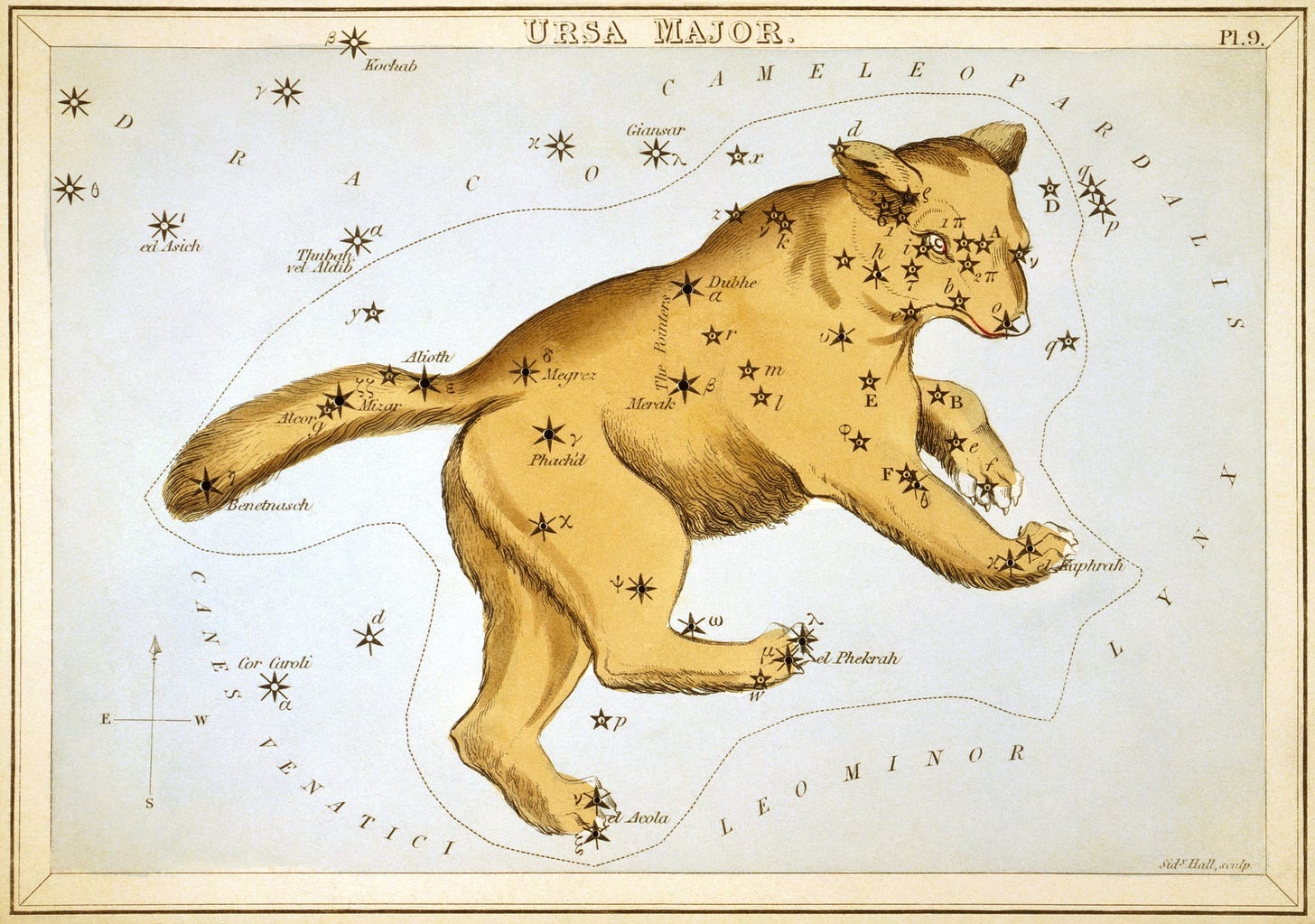

Linguists have traced the development of the PIE h₂ŕ̥tḱos through four separate branches of Indo-European as *rktho- (Italic), *rkto- (Greek), *rkso- (Indic), and *rtko- (Celtic). Thus, we find that the ancient Greek word for bear is arktos, from which is derived the star name "Arcturus," which means "guardian of the bear" (owing to its position behind the tail of the bear in Ursa Major), and we later inherited the adjective and noun "arctic," meaning "north," – a term which again refers to the northern constellation of the bear. Although it doesn’t seem at first glance like it’s related, the Latin word for bear, ursus, is also derived from this PIE root. The constellations Ursa Major (a.k.a. the Big Dipper in English), and Ursa Minor and the English adjective "ursine," which means "bear-like," come from this line.

Sidney Hall’s Ursa Major illustration from Urania’s Mirror, a set of 32 astronomical star chart cards with holes punched in them so they could be held up against a light and the constellations would appear on a wall — which must have been a very charming evening entertainment.

The French word for bear, ours, and the Spanish oso are also derived from the Latin. The ancient Brythonic Celtic tongue had a similar bear word (*arto-), from which the Welsh word arth and the name Arthur are derived,11 as well as the names of the Celtic bear deities Artos, Artaius, and Artio.

This bronze figurine of the goddess Artio, who is depicted seated on a throne that is now missing as she feeds fruit to a bear, was found in Bern, Switzerland in the Muri statuette group. Its base is inscribed with the dedication Deae Artioni / Licinia Sabinilla [To the Goddess Artio / from Licinia Sabinilla]. It has been dated to the late second century CE.

The PIE *rkto- words disappeared from most of the more northerly languages, and only reappeared later when their speakers borrowed Greek or Latin terms, such as the names of constellations.

In these languages, the animal was assigned noa-names that come from two (proposed) PIE roots:

Donald Ringe has suggested *ǵʰwer-, which refers to pretty much any wild animal: to wit, he is suggesting that bears were simply referred to as “the beast.” This is a euphemism that uses a general expressions to stand in for something specific that both the speaker and the listener have a clear understanding of. For example, hinting at “doing the deed” when referring to sex, or only saying “that guy” instead of, for instance, “Fred, the asshole who steals food from the break room fridge.”

Alternately, the same words may be based on the etymological root *bher-, which means both “bright” and “brown”.12 *Bher- probably gave rise to the Proto-Germanic *berô – and the creature’s noa-name further evolved into bero in Old High German, björn in Old Norse and Swedish, and bjørn in Danish.13 All of these *bher- words refer to the animal as simply “brown/the brown one,” and seem to lead directly to modern English “bear” or German Bär. The less common variant "bruin" also stems from *bher-, as do the French words brun and brunette —

— and, of course, the name Bruno.

(And we don’t talk about Bru(i)no, no, no!)

We don’t talk about Bruno in more than 21 languages!

In the Baltic lands, an alternate form of the taboo sometimes avoided naming the creature by relying on description instead of characterizing it by the color of its fur. Focusing on its texture of its hirsute hair suit, they called it lokys in Lithuanian, lacis in Latvian, and clokis in Old Prussian, which all probably come from *tlakis, meaning hairy or shaggy.

In the Slavic-speaking lands, people preferred to describe the animal’s habits instead of its appearance, so the bear is called medved in Russian, medvěd in Czech, and niedźwiedź in Polish — the “honey eater.” A similar concept arose in Middle Welsh when they called the beast melfochyn – the “honey-pig.”

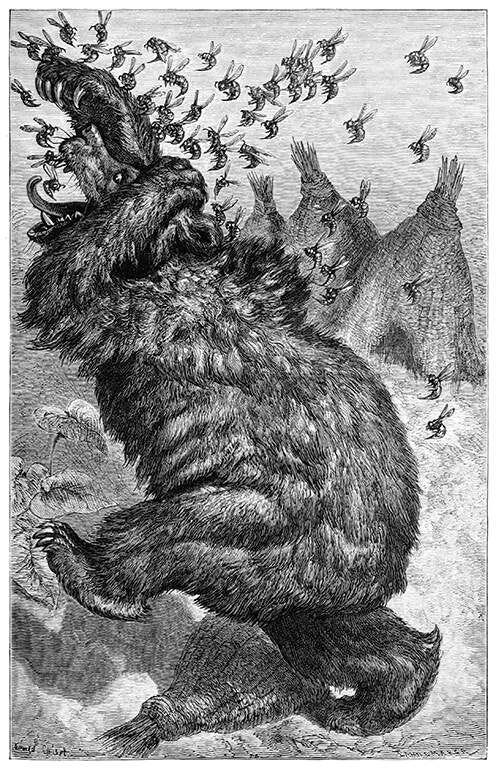

“The bear in the beehive” woodcut illustration by Adolphe François Pannemaker for an 1869 edition of Aesop’s Fables.

Finnish, which is not an Indo-European language, calls bears karhut. Several non-noa ways they refer to the bear include Karhu, and Otso or Ohto. These proper names treat the bear as a collective (animistic) spirit, and they are connected with both myths and rituals. The oldest myths about Otso are about his marriage with the primordial mother of all human beings. This relationship was reflected in the ritual of Peijaiset, in which the bear spirit was symbolically returned to its family through marriage. Mongolian uses apotrophaic terms that flatter the bear by referring it using words that mean father, grandfather, or ancestor (elderly male relatives), and I’m sure there are deeper dimensions to this as well.

I have also seen (though not yet investigated) a claim that Rane Willerslev. in the book Soul Hunters reported that a Yukaghir hunter mentioned hunting the animal, which he called a "Russian in fur boots." This is super interesting, because it reflects a shifting of the taboo onto a rival ethnic group.14

Noa-names for wolves

The PIE term for wolf is speculated to be *wlkwo-, and a taboo may have motivated a change in one or two of the sounds so that the "kw" shifts to "p." This means *wlkwo- became *wlpo- , the basis for old German *wulp- which through regular sound change becomes *wulf- and then the Proto-Germanic *wulfaz. A similar sound taboo gives old Italic *lupo- (either by reversing the order of *wlpo- to *lwpo-, or dropping the initial 'w' sound and inserting a 'u'. This then yields the lupus. The Greek and Slavic didn't change the ‘kw’ to ‘p,’ so we get λύκος (lýkos).15

Swedish may be the only Indo-European language that replaced its original term ulv (“wolf”) with a completely different word: varg (“stranger”). But more on that later …

Sometimes, the taboo was limited by mythical constraints. For instance, in northern Germany it was forbidden to say the word “wolf” during the twelve days of deepest winter. This Wolfzeit was “bathed in a black sun,” because Sköll and Hati, the two wolves that represented the forces of evil, were on the prowl for the Sun, which they wished to devour.16

The case of the Irish words for wolves is interesting, because the old word for wolf still represents the idea of evil modern Irish language: olc means "bad,” “evil,” or “misfortune," but the more recent terms for the wolf as an animal are completely different: faoil and cú allaidh (which mean “wild dog”), and mac tíre, which, poetically, means “son of the earth.”

This contemporary Celtic-style illustration was borrowed from here.

Wolves were also given noa-names well afield of the Indo-European language areas. For instance, Mongolians properly call the wolf чоно (ᠴᠢᠨᠣᠠ), but noa-names used for it include хээрийн нохой (ᠬᠡᠭᠡᠷᠡ ᠵᠢᠨ ᠨᠣᠬᠠᠢ) kheeriin nokhoi “dog of the steppes/wilderness” or хээрийн юм (ᠬᠡᠭᠡᠷᠡ ᠵᠢᠨ ᠶᠠᠭᠤᠮᠠ) kheeriin yum “thing of the steppes/wilderness,” or боохой (ᠪᠣᠬᠠᠢ) bookhoi. These terms are marked in Mongolian-English and Mongolian-Chinese dictionaries as “taboo names” or “euphemistic names.”17

The non-Indo-European Hungarians call the wolf farkas, which is derived from root words meaning “animal with a tail.” If we consider that many, many animals have tails, this synecdoche is like euphemisms that functioned like a wink or nudge to indicated which animal was meant. (As in the examples I provided above, such as “doing the deed” or “that guy.”)

The Hungarian word fene is a demon of illness, and a fene egye meg! means "Let it be taken by the fene!" — it’s an expression of frustration when things go badly (this is a mild curse, like “to heck with it!”) What is interesting for our purposes here is that this expression also has an alternate form, farkas vigye el! — which, as you might imagine, means “Let the wolf eat it!”

And this brings us back full circle to an equivalence with diabolical equivalencies: “The devil take it!”

Names inspired by wolves and bears

Nomen = omen. As a teen, this Norwegian black metal musician chose to perform using the name Old Norse name Varg instead of his given name, Kristian. Varg Vikernes began a promising musical career in the early 90s, but he was convicted of murder and arson in 1994. In prison he became a neo-Nazi, and after his release he moved to France. In Norwegian and Swedish, the name Varg means wolf, as well as “criminal” or “outlaw,” or “destroyer” — all of which fit him pretty well.

Even prior to the advent of Nordic Black Metal, some people named themselves after wolves and bears. It’s likely they believed that assimilating the qualities of these animals might be protective, so one finds names such as the Gothic Ulfila; the German Wolfgang (which means “traveling wolf” or “wolf path”); Velvel or Velvl in Yiddish; and Vuk or Vukan in Croatian, which all refer to wolves, as does Rudolf (“famous wolf”) and Adolf/ph (“noble wolf”). Equivalent bear names are Metko or Medo, and then Urso and all the variations of Ursula as well as Arthur, as I discussed above.

Some larger collectives have named themselves after wolves, including Irish clans whose names are derived from Faol. The names used for the Caucasian nation of Georgia are derived from their name in Old Persian: vrkān (𐎺𐎼𐎣𐎠𐎴) meaning "the land of the wolves." This would eventually evolve gorğān, a term that entered most European languages as some version of "Georgia."

The wolf is also a national symbol of Chechnya. According to folklore, the Chechens are "born of a she-wolf," as included in the central line in the national myth of a "lone wolf" that symbolizes strength, independence and freedom. A proverb about the Chechen teips [clans] is that they are "equal and free like wolves."

There are many more examples, but I’m going to have to stop here.

Third time’s the charm?

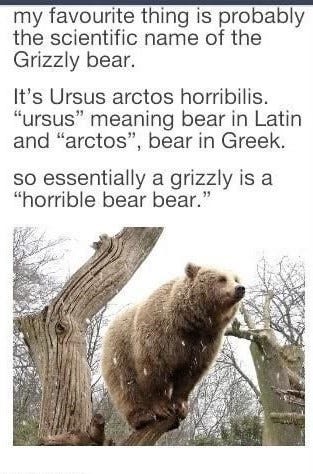

In bygone days of yore, devils, wolves, and bears were at some times beings we wanted to keep so far away that we didn’t even dare speak of them directly. However, later we got a lot more comfortable with them. (Perhaps the huge reduction in their numbers had something to do with this.) Carl Linnaeus’s term for the Eurasian brown bear, Ursus arctos arctos flaunts his liberty in taking its name in vain: in a mixture of Latin and Greek, he calls the huge, shaggy, bipedal honey-eater a “bear-bear-bear.”

Friend-shaped

As for the wolf, Linnaeus seemed to allude to its familiarity (family status), when he named it Canis lupus: the dog that’s a wolf, while dogs are Canis lupus familiaris – the dog that’s a wolf that’s a member of our family.

This painting by Jackie Morris illustrates a beautiful idyll where a woman and a small pack of wolves tell stories and dream together on a long winter night.

Make sure to subscribe so you won’t miss upcoming posts on the similarities between devils and wolves, and on Corn Wolfing as a writing technique.

Illustration of Marchocias, from J.A.S. Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire Infernal (Paris, 1863): "The grand marquis of hell appears as a fierce wolf with griffon’s wings and serpent’s tail and spits fire." Source: Cornell University Library. Why does “he” seem to be lactating? Let’s talk about that later.

A wolf shows up again in another or Terence’s lines from his Phormio: Auribus teneo lupum, nam neque quomodo a me amittam invenio neque uti retineam scio [I’ve got a wolf by the ears; for I neither know how to get rid of her, nor yet how to keep her]. It refers to dilemma of either holding tightly to a dangerous situation or letting it go, knowing that either choice may to lead to disaster.

This seven-year-old photo of my daughter pressing the ears of a huge wolfdog is for illustration purposes only — don’t try it with a wild wolf or a wolfdog you aren’t already extremely friendly with:

My kids? They were raised by this wolfdog (whose name is Helli) and vice-versa — they have also helped raise her litter of pups.

See www.lupus.org.

However, eventually forest managers had a change of heart. One example is the forest ecologist Charles Newton Elliott, who recognized that wolf trees greatly contribute to the diversity and quality of their ecosystems. It would be many decades later before wolves would receive similar acknowledgement for their service to the life around them. And I believe the expression “wolf tree” currently carries these positive connotations forward.

Also see the article at Atlas Obscura: “When Tomatoes Were Blamed for Witchcraft and Werewolves” and tell the story the next time you serve a caprese salad or marinara sauce to your friends or family.

The concept of language being so powerful that the word is exchangeable for the thing is ancient. Myths, such as the story of Adam and Eve naming animals in the Garden of Eden reflect a belief that each thing — person, animal, god, spirit, or object—has a true name, and that knowledge of that true name grants one power of it.

This means that a) one’s “true name,” which may be given in an initiation, must be carefully guarded, because if someone finds it out they may be able to abuse it in terrible ways; and b) knowing the names of gods, angels, demons, etc. and following certain ritual protocols gives one power over them.

The Codex Gigas is the largest extant medieval illuminated manuscript in the world. According to Wikipedia, a legend that was already recorded in the Middle Ages tells that the Codex’s scribe was a monk who broke his monastic vows and was sentenced to be walled up alive. In order to prevent this, he promised to create, in one night, a book containing all human knowledge that would glorify the monastery forever. The work didn’t proceed quickly enough, so when midnight drew close, in desperation he prayed to Lucifer to help him finish the work in exchange for his soul. Lucifer completed the manuscript, and the monk added his portrait as a tribute to his patron.

By contrast, tomte comes from the word tomt — a plot of land, so its name means “homestead man.” This indicates it’s more of a land spirit than a protector of the family as such.

“Apotropaic” means when something is believed to have the power to avert bad luck or evil or harmful influences.

Sara Mastros has suggested the alternate term “apotropaic cryptonym” for these expressions. I find her suggestion just as conceptually sound and less tied to a concepts that arose in a particular culture. I’ll leave it to readers to decide whether they prefer the more standard, yet “exotic” terminology, or the less-known and more general expression.

An asterisk marks hypothetical reconstructions, and when alternative forms are offered, as here, it is because the proposed root words are speculated rather than known with certainty.

The commonly proposed etymology of Arthwyr = bear man is not widely accepted by scholars today. Rather, the preferred one claims that Arthur is derived from the Roman family name Artorius, which could have been a Latinized form whose roots were *Arto-rīg-ios: son of the bear/warrior-king. While this patronym is unattested, *arto-rīg, "bear/warrior-king" is the source of the Old Irish personal name Artrí.

Some linguists quibble that the concept for the color brown was a much more recent addition to Indo-European languages, but I am not going down that rabbit hole here. If you don’t like the second proposed lineage for bruins, use the first one.

Thanks are due to Aino Sund for some of the spellings of the Scandinavian variations and for catching a silly error that I have already corrected.

See the discussion in this UPenn linguistics blog.

We can see a similar movement from devil to “debil” in English, with the latter being a contemporary avoidance word, or, more precisely a minced oath (this term includes words such as heck, dang, shoot that serve as substitutes for other words, as well as short forms such as ‘sblood or WTF).

However, debil one that reflects distance and mockery from the original referent in contemporary usage, much like the switch from Jesus to Jebus/Jeebus, which was originally an authentic minced oath, but now is primarily used to satirize fundamentalist Christians and their beliefs. In these cases, the avoidance being conveyed by a writer or speaker is intended to prevent their accidental identification with those who actually believe in the devil.

The unfortunate part here is that debil means “idiot” or “weak person” in languages that span Europe from Portugal to Russia. The use of debil in these languages, does not stem from demonology (the ecclesiastical Greek diabolos). Rather, it comes from the Latin root debilitas — which gives us the English words “debility” and “debilitate” — so it is an ableist slur. Perhaps the non-English meanings have filtered into English in a semiconscious way, which is why the word is increasingly catching on for the purpose of mocking something that was once feared by many and is still feared by a few (who are perceived as mentally weaker). However, I believe it is better avoided.

To my surprise, I found that the baby name web myfirstnamerocks.com has a page dedicated to Debil as a name, and they state: “Debil is a name that signifies a freedom-loving and free-spirited individual. Nothing is conventional with your love of change and adventure. You make sensible decisions very quickly, especially in a dangerous or difficult situation. You are inquisitive and often ask others ‘Why this?,’ ‘Why that?,’ or just plain “Why?’ Multi-tasking is a breeze for you – eat and watch TV at the same time!” This doesn’t seem to be a satire page or a prank – it’s just AI blather.

See the pianist and wolf philanthropist Hélène Grimaud’s extraordinary autobiography Wild Harmonies: A Life of Music and Wolves. NY: Riverhead Books, 2006, p. 21.

See the comments in the LanguageHat blog article.