Rewilding Bees

What do colonialists, Nazis, communists, and capitalist agribusiness all have in common? Replacing and suppressing native pollinators - and here's what you can do about it.

Until 2016, we kept bees at my homestead. I used to practice yoga in the apiary, stretching and breathing rhythmically in the golden glow of the sun on new wood, the heady perfume of honey and propolis and the vivifying buzz of the bees’ energy. The dream ended when our bees caught European Foulbrood, probably brought to the area when the monastery across the river imported a whole trailer truckload of bees. To save money, they bought them from a region of Italy known to be rife with the devastating disease. Twice, we had to burn the hives in front of veterinary inspectors, and — since foulbrood spores are persistent in the soil — we have never renewed our apiculture.1

My hives in flames in 2015 — the first time.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The sweet secret of rediscovery

On a fine summer day a man I will call Karel (real name withheld for reasons that will become clear later) took a walk in a South Bohemian forest where the evergreen trees were dripping with honeydew that ants, flies and wasps were feasting upon. At the same time, only a few hundred meters away he noticed his purebred Carniolan honey bees languishing around their hive, looking out at him from its entrance and not making a move toward the rich source of nourishment dripping from the trees. Fourteen days later, they were starving and had to be rescued with tanks of sugar water, and he said to himself: “Damn, what kind of bees are these if they can’t make use of what nature offers?”

The forested hills of the Šumava, South Bohemia. Onebigphoto.

As he later discovered, the problem lay in a mismatch between the type of bees that is predominantly bred in the Czech Republic and the environment they were living in. Like many beekeepers, he knew that fugitive colonies of indigenous dark bees were sometimes found far from civilization, but his recognition that imported breeds failed to make use of what the native bees instinctively sought as food sources was a first step toward applying the principles of bioregionalism to beekeeping. This experience made an activist out of him.

Thereafter, he began seeking wild colonies of Apis mellifera mellifera, the Dark European Honey Bee, luring swarms to his deep forest apiaries, carefully checking morphometric data to compare them with pure specimens, and making efforts to educate other beekeepers about restoring this pollinator to its original habitat.

The challenge, he told me, was that the native subspecies has been banned, suppressed, and successfully extirpated in many of its original habitat areas, and anyone who keeps these bees is subject to legal action and vigilante attacks. Moreover, the beekeeping organizations opposed his efforts.

Karel’s photo of a wild colony.

Honeybees as an invasive species in the New World

All things have their places. In the case of Karel and his wild colonies, it’s a case of a well-adapted native subspecies being replaced with one that better serves the needs of agribusiness, but is not so well to surviving local conditions.

In the Americas, it’s not as subtle as two competing subspecies. We are used to seeing passionate appeals to “save the bees,” but the relevance of this framing of the insects’ position in the ecosystem depends on where you live. However, the first animal we usually free associate when we hear “pollinator,” Apis mellifera, is not native to the Americas. It is true they are responsible for putting a large percent of the food we eat on our tables, but that is because they are servicing imported crop plants.

Because European honey bees are able to out-compete many native North/Central/South American pollinators, such as solitary bees and bumblebees, beetles, moths, and butterflies, they can be considered an invasive species, or — at best — feral livestock like the infamous feral hogs.

Above: Thirty-Fifty Feral hogs, the source of many popular memes. Image source.

The bees’ primary purpose is to serve agriculture, but their range goes beyond cultivated fields and orchards, and they put pressure on native pollinators by monopolizing floral resources, especially in marginal or stressed ecosystems. They can also spread diseases to the native bee species, because many beekeepers maintain them in unhealthy, unnatural, and unhygienic conditions.

The image above is problematic for several reasons: it globalizes Apis mellifera and the agriculture based on it (look at the positioning of N. America); it ties into the misinformation that suggests all life on Earth will end without bees; and it also implies that “the world” ends if/when human activities fail.

The concept of “saving the bees” can be conceptualized in a broader way that does not only serve an agribusiness agenda, as I will again discuss toward the end of this article.

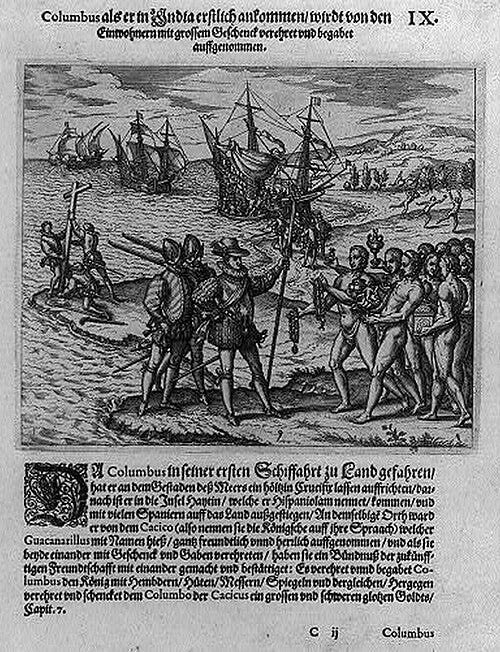

Christopher Columbus’ first crime

The history of Europeans messing with native apiculture in the Americas goes all the way back to the fifteenth century. Among his many, many other atrocities,2 Christopher Columbus was a honey thief. On Sunday April 10, 1496 the captain and his crew stole honey and beeswax from the Indigenous Arawak People. Normally, they would not have set anchor on Sunday, considered a holy day of rest, but the crews on his boats were hungry, so they went ashore, threatened the native people with gunshots, then pillaged their homes, stealing beeswax and honey from the stingless Melipona bees the villagers kept in hives. They feasted on this dripping plunder back on their boats.3

Columbus’ Arrival in the New World on Hispaniola, 6 December 1492; Received by Arawak Indians. Copper engraving by Theodor de Bry, ca 1594. Wikimedia.

Europeans BYOB (Bring Your Own Bees)

Indigenous people throughout the Americas already had extensive apicultural, culinary, spiritual, linguistic, technological, and ecological relationships with their native bees, long before this unfortunate encounter. However, European colonizers discounted all of this when they crashed onto the shores of what they called the “New” World.

Many sought a Promised Land corresponding to the Biblical verse: “If the Lord delights in us, then He will bring us into…a land which flows with milk and honey” (Numbers 14:8); a land that should be awarded to the faithful. Although cattle and honey bees did not exist in North America, the powerful vision of having them (and the beef, milk, wax, medicine, candles and clothing provided by them) drove colonizers’ efforts at claiming, then altering the landscape; for when the milk and honey would flow, then the New World Christians would know that they had the seal of God’s blessing upon their endeavors.4

The Land of Milk and Honey, from a defunct blog.

If there was to be that much honey, and if European crops were to flourish, they needed Apis mellifera. The first European honey bees were brought to the more northerly territories of the New World in the 1620s, the insects quickly spread throughout the new land. “The bees have generally extended themselves into the country, a little in advance of the white settlers. The Indians therefore call them the white man’s fly, and consider their approach as indicating the approach of the settlements of the whites.”5

Native observers noted that European honeybees preceded the white man, flying ahead of his next settlements, and plantain (Plantago major), which became known as "white man’s footprint” followed upon his heels. it is generally believed that dandelions, which are native to Eurasia, were brought to North America on the Mayflower, and to this day North Americans are told to let dandelions grow in their yards to “save the bees.”6

P.lantago major (aka “White Man’s Footprint”), in Atlas des Plantes des France. 1892. Wikimedia

Although many Indigenous cultures had their own beekeeping traditions, they observed and learned how to utilize the new species as well. Traditionally, they used sugar maple, birch, bulrush and other sources of sweetness in their cuisines, but they began adding honey from Apis mellifera to their diets, and began to participate in the trade in forest honey and beeswax, and to use the bees’ propolis to seal their canoes.7

European honeybees and Apis mellifera mellifera

Let’s turn back to the Old Continent: honey bees spread across Europe in the post-glacial warming period about 8000 years ago, when ice gave way to tundra, and then to dense forests. The seven species within the Apis (honey bee) genus are further divided into several dozen geographic subspecies or ecotypes, each with its own particularities in morphology, temperament, foraging habits, etc.

Apis mellifera mellifera, the dark subspecies of honey bee, originally emerged from the Mediterranean coast, where the encroaching glaciers had pushed it during the last Ice Age. From there, it spread across a vast territory spanning from the Pyrenees in the West, reaching the British Islands (which separated from Continental Europe only about 6000 years ago, so there was no necessity of flying across the Channel) to Scandinavia to the North, the Urals to the East, and the Alps to the South.

Apis mellifera mellifera, photographed by Tauno Erik. Wikimedia.

Where I live (in Central Bohemia, the western part of the Czech Republic, in the very heart of Europe), few laypeople know that the bees commonly kept are not indigenous. Beekeepers know, and most have a low opinion of the native bees and express the wish that if any are still alive that they should be exterminated post haste. The Dark European Honey Bee is distinguished from other subspecies not, as you might think, mainly by its color (for other bees can also be quite dark) but by other morphological characteristics such as wing venation and abdominal hair length, its colony size and “brood rhythm” (the timing and rapidity of colonies’ increase in size during their active season), the plants from which it collects pollen (it recognizes and collects from many more plants than non-native bees), and, finally, genetic traits that are revealed by DNA analysis.

Not surprisingly, this breed has a longer collecting season than those introduced from southern climes: it gets out earlier in the morning and earlier in the season than imported bees, and stays out longer in the evening and at the season’s end. Queens are also able to complete their nuptial flights in cooler weather. As Karel noticed, dark bees utilize honeydew when the nectar flow is low, and they have been observed visiting many more species of native plants. They know how to deal with the the kind of honeydew that creates melezitose, the so-called “cement” honey that can mean death for other bees, and they are even able to winter on it. (Fancy-breed honey bees cannot winter on any honeydew honey, because its protein content is too low.)

Dark bees also show promise for their greater resistance to the parasitical mites that plague modern beekeepers, and they are more effective at ripening their honey under wet or humid conditions. Finally, they are prodigious in the use of propolis, which has traditionally been considered a hassle by beekeepers (it causes sticky, messy hives whose frames can become harder to manipulate), but in recent times there has been much renewed interest in the raw material, and propolis is a powerful natural antibiotic for the hive, so this does not have to be a disadvantage.

Why would anyone want to get rid of such a useful creature? During the 19th century there was a move toward greater rationalization in bee breeding: having become aware of the differences between “races” of bees, breeders sought out the most desirable traits, such as bountiful honey production, gentle disposition, resistance to diseases, and lack of inclination to swarm. Each of the known breeds had its proponents and detractors, and there was much planned and unplanned cross-breeding. However, unlike with dogs or larger livestock it isn’t possible to bring the males and females you have selected directly together. A maiden queen departs her hive when she is ready, and will breed with whatever drones she meets on her nuptial flight, high up in the air, away from prying eyes. Any attempts at creating a pure breed have to be carried out in geographically isolated locations like islands or valleys, or else by exterminating “undesirables” in order to change the local population as a whole. (Artificial insemination techniques were developed in the 1840s, but they have distinct disadvantages for the health of the queens and their offspring.)

The original dark bee of Bohemia was renowned for its gentle disposition, but during the wild decades of experimentation with all kinds of foreign breeds, this congenial trait was lost. Thereafter, dark, aggressive hybrids replaced their foremothers, and the reputation of the original stock was tainted by the genes they acquired in an age when many would-be “improvers” of bee stock were only concerned with honey yields. This would taint its reputation for many generations afterward.

A fugitive in her own realm: the Apis mellifera mellifera queen is the bee with a longer body and a dab of paint on her thorax. The beekeeper holding her little box has been threatened with lawsuits by the official beekeeping organization — for daring to return native bees to their traditional habitat.

One of the foreign breeds that was particularly favored then, and to this day remains the world’s second most widely-kept bee is the Carniolan (Apis mellifera carnica). This bee thrives where there are large, easy sources of nectar that beekeepers could bring them to in mobile apiaries; thus, Carniolans are exceptionally well suited to service agricultural monocrops. When late crops like buckwheat started to be replaced with oilseed rape, and when pastureland gave way to amber waves of grain that stretched to the horizons, the moderate-paced and flexible brood rhythm of the native bee did not allow synchronization with a nectar flow that all came in one big rush.

The native bees were thus pushed aside as inefficient as well as being considered ill-tempered. However, the imported Carniolans bees really can’t manage outside of their native habitat without being fed supplementary sugar between nectar flows and before the winter. In previous ages, sugar was a luxury reserved only for the elite, and certainly not something farmers would feed to livestock, but this changed with the industrialization of sugar beet refining at the midpoint of the 19th century. At that point, since beet sugar was much cheaper than honey, they were welcomed to feast on the sweet abundance. Once this shift had taken place, the replacement of native dark bees with Carniolans and Italian bees (Apis mellifera ligustica) seemed fated.

It gets worse: another Nazi genocide …that you never heard about and which never ended!

We all know that the Nazis had some very peculiar ideas about heredity and race. Their theories have been discounted by scientists, their laws abolished and policies abandoned, and their actions decried as abominations. All except in the field of beekeeping. Surprisingly, Nazi-era policies still remain on the books in some countries. And the bees they repudiated are still slandered as lazy, dark nogoodniks who carry diseases and contaminate the pure, hardworking, productive race that deserves the state’s and every citizen’s support.

Ordinances still in effect say: if the origin of a colony found outside of an apiary is not known (this includes all wild colonies in forests and abandoned places), it is to be exterminated, and many beekeepers will eagerly carry out the task. Karel would know: until his fateful realization he had also been one of them. No annual beekeepers’ meeting, at least where I live, is complete without exhortations for everyone to join in this effort.

Cultural historian Bee Wilson (yes: that’s really her name!) suggests in The Hive: The Story of the Honeybee and Us that bee colonies have been used since ancient times up to our own to represent almost every type of political system:

Bee politics has taken almost as many forms as human politics, shifting with the changing values of different places and times. The hive has been, in turn, monarchical, oligarchical, aristocratic, constitutional, imperial, republican, absolute, moderate, communist, anarchist, and even fascist. As so often in politics, we see what we want to see.8

Nazi beekeeping magazines “served the regime and used bees and bee colonies (Bienenvolk) as examples for humans by praising qualities such as ‘performance by community” by putting forward slogans such as ‘you are nothing, your Volk is everything’, and by commending virtues such as diligence, cleanliness, and the willingness to sacrifice and to do one’s duty.”9

In parallel to the Lebensborn programs in Germany, Austria, and Norway where SS officers tried to spawn “racially and genetically valuable children” with selected women, beekeepers throughout the Reich were **required** to bring their virgin queens to the newly established breeding stations. There, they were allowed to emerge in an area that had been cleared of all other drones than the Reich’s preferred Carniolans, which were celebrated as the new “German” (rather than Balkan) bee.

The Nazi party made it illegal to keep other breeds, and passed ordinances that require beekeepers to kill colonies found in the woods or abandoned properties.

Central Europe’s communist regimes maintained these extermination orders on the books, and to this day, they are still enthusiastically carried out. Anyone who dares to keep native bees, protect wild colonies, or promote their re-introduction from foreign stock risks persecution, prosecution, official harassment, and vigilante vandalism from other beekeepers. These misguided practices of course play to the interests of those who breed and promote Carniolan honeybees, as well as those who promote the industrial style of agriculture, so it will require much determination to contend with these forces and restore the native bee to its homelands.

Is there hope for dark bees?

While economic and political pressures drove the dark bee out of many of its original territories, in some countries (outside the Czech Republic) it is enjoying a modest resurgence. These include: parts of England, Ireland, Switzerland and Sweden, Poland, Belarus and Russia. In the British Isles its comeback is supported by BIBBA (the British Isles’ Bee Improvers & Bee Breeders Association). An organization called SICAMM: Societas Internationalis pro Conservatione Apis Melliferae Melliferae [International Society for the Protection of the European Dark Bee] brings together beekeepers, researchers and national-level organizations to promote conservation and re-introduction of dark bees within their native habitats. The success of some of the breeding programs abroad provides a glimmer of hope that even here in Czechia we may be able to create an official bioregional experiment, and perhaps even force a change in the local laws, especially if we are able to leverage EU pressure in the name of reintroducing native species, which is supposed to be a policy objective.

Of course any animal or plant that was originally part of an ecosystem should have a chance to return there, and supporting biodiversity (of appropriate species) is an end in its own right, but the final reason why I feel the Dark European Honey Bee ought to be restored to the forests and meadows, and to the human-created agricultural landscapes of Central Europe, is that given its greater ability to survive in its native habitat without the need to have its diet supplemented with sugar solutions or its health needs met with chemicals, it is particularly much better suited to organic apiculture and to serving the pollination needs of diverse small farms and gardens. It can be the harbinger of a return to a more human-scaled horticulture. Alternately, at least it has a better chance of surviving a total collapse.

Pollinators in crisis

Anyone who keeps up with current media knows that honey bees are beset with problems. This is true wherever honeybees are kept, and it is true for all the species and subspecies.

Researchers paint a bleak picture, where the bees suffer from a complex interplay of factors that includes deforestation, loss of foraging lands, monocultures, parasitic mites, viruses, fungal brood diseases, environmental toxins, lack of genetic diversity, unnatural and unsustainable beekeeping practices, and, finally, as legendary mycologist Paul Stamets suggests, even the loss of mycelial networks in forests that provide bees with substances that help them up-regulate their immune and detoxification systems in order to effectively contend with the increased burden of diseases created by all the above-named factors. I strongly recommend watching Stamets' video, linked here and in the list of References to get an overview of the process.

The significance of the threat to pollinators for the American agricultural system is staggering. It is said (though it’s likely an overstatement) that one third of the food Americans eat is directly pollinated by bees and perhaps 75% of our food is influenced indirectly by pollinators of one kind or another.

What beekeepers can do:

First of all, see if you can keep bees that are native to your region. But whether or not you determine to acquire your local native breed, see if you can get your bees from beekeepers living nearby who a) have, in your judgment, good, sustainable beekeeping practices and sweet tempered bees; and if possible b) whose stock has been around for 20+ generations, which should ensure their better adaptation to local climatic conditions and sources of food. Such bees are more likely to thrive in your apiary, as they will be more used to the local weather fluctuations and possibly more adapt at seeking out sources of sustenance. Bees’ genetic memory of food sources makes a difference, but so does experience. Talk to old hands and wonky types who keep up on the recent scientific literature.

Come up with definitions of what a successful colony should look like: are you only interested in maximizing honey yields? Do you want your colonies to survive without having to add sugar to their diet? Are certain diseases or parasites prevalent in your area, and do you need bees that are better able to resist them? Find out which breeds have been most successful in your area, but also consider well adapted nonpedigreed or mixed-breed bees.

If you are not going to follow monocrops with your beehives in trailers, a next step to help your girls bee all they can bee is to talk to your local farmers and gardeners. Notify them where your apiaries are located. If they are not organic-friendly, see if they will at least minimize spray applications near the beehives, refrain from spraying plants that are currently in bloom, and do their dirty work in the evening hours when bees are not on the wing. However, if they are growing plants from seeds treated with systemic neonicotinoid poisons your bees are still in trouble. The toxic chemicals have already been taken up and circulated to all the tissues of the plant, including leaves, flowers, roots and even the pollen and nectar – where they are then picked up by bees. Even at the time of sowing, there was collateral damage to the environment from the talc that is mixed in with seeds that are prepared with sticky neonic coatings. During planting, the excess talc blows up into the air and then spreads the joy around the local ecosystem.

If you are keeping bees and use movable frames (rather than top-bar hives that allow bees the freedom to determine their own cell sizes) look into research on cell size for wax foundations. I can’t tell you what’s best, because it depends on your local conditions. However, what’s commonly offered on the market is a foundation stamped with larger cells than the bees would build on their own. Bigger-than-life standard cell sizes were introduced to encourage the development of bigger bees with longer tongues and larger honey sacs, but not necessarily healthier or more aerodynamic insects. Among other things, a more appropriate cell size allows bees to optimize their internal mite control, improve resistance to secondary infections, and control the length of time worker larvae require to develop into mature bees, and this choice may even improve their disposition. You can read more about this at beesource.com, or on Dave Cushman’s website: If you have a local co-op of like-minded beekeepers or are planning a larger beekeeping operation, you may want to invest in your own wax foundation press, which not only lets you choose the size of the cells you prefer, but gives you the peace of mind of knowing the quality of the wax that is being put into the hives (it’s not contaminated with paraffin or other cheap substitute materials that compromise its strength and quality).

Bees kept by humans need health care, so use your plant and mushroom medicines (though please, for the love of whatever you consider holy, not Cordyceps! There are some indications that it has infected honey bees in India) and other preparations that are closer to nature than commercial antibiotics and miticides. Also, don’t play with concentrated essential oils in your hives, as the unnaturally powerful scents are said to cause havoc in the bees’ pheromone communication network. Richters Herbs provides a list of herbs that may be useful to beekeepers for treating their colonies. From our own experience, I can recommend treating nosema infestation with yarrow tea (soaked into a sugar solution), and killing varroa mites with easy-to-use formic acid products. Other beekeepers we know use thymol, or slightly fussier preparations of oxalic acid, which can also be good choices for mite suppression. Don’t just count on Uncle Darwin to sort out the weak from the strong: keeping on top of mite infestations benefits not only your own bees and your neighbors’, but also wild colonies.

Vintage illustration from the E. Public domain.

What consumers can do

I strongly urge everyone to buy honey directly from their local beekeepers, who can often be found at farmers’ markets. The next best choice might be a local, independently-owned health food store. Do not buy honey at supermarkets, where according to pollen analysis, up to 70% of what is sold as “honey” by rights should not be so called. (Even worse are drug stores, where 100% of analyzed samples failed ID tests).

Sometimes these rip-off products are labelled just as “honey,” but other times they are called “filtered honey,” a designation that actually means ultrafiltered, referring to a process that removes the pollen. Although the FDA considers these products not to be honey, they do not inspect products sold as honey to see if their contents are in accordance with their labels. So why would anyone filter out the good stuff? Mark Jensen, president of the American Honey Producers Association stated: “I don’t know of any U.S. producer that would want to do that. Elimination of all pollen can only be achieved by ultra-filtering and this filtration process does nothing but cost money and diminish the quality of the honey. In my judgment, it is pretty safe to assume that any ultra-filtered honey on store shelves is Chinese honey and it’s even safer to assume that it entered the country uninspected and in violation of federal law.”10

Without telltale pollen in the sample, a honey’s origin is impossible to trace; furthermore, it may be contaminated with antibiotics and heavy metals, and is likely to be adulterated with sugar syrup solutions. It also does not crystalize, which gives consumers the runny consistency they prefer (especially if they are buying it in squeeze bottles). So caveat emptor: if you can’t get honey from someone you know, read the label carefully because the FDA does not have your back on this one.

Real honey crystalizes – if this happens to yours, rejoice, because you have the genuine article. If you really need it to be liquid and don’t just want to savor those sweet, crunchy crystalline nuggets, heat it up gently to 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 C), or in a pan of warm water. Do not microwave it, and please, please, do not buy those plastic squeezee bears, not least of all because it isn’t possible to safely re-heat crystallized honey in them — you’ll end up consuming a bunch of microplastics and other undesirable residues.

By buying honey from someone whose hand you can shake over the deal, you are supporting individuals who pursue an honest livelihood and whose activities benefit the ecosystem and farms and gardens in their – and your - vicinity, and you are less likely to get ripped off with products that look and smell like honey but are actually glorified sugar syrup with chemical additives.

Real, local honey will also benefit your health: consuming tiny amounts of pollen that the bees collected from plants growing nearby is said to help prevent and treat allergies. And the final argument for local raw honey is pleasure: like wine and cheese, honeys also contain an unmistakable terroir; the flavor of the blossoms brought forth from the land around you, which makes a luxurious addition to any locally-themed feast.

Lastly, knowing my readership here, I feel it’s necessary to pass a reminder about “open carry” of honey at picnics and as offerings. If we want to prevent the spread of diseases (which may be devastating to bees, though harmless to honey-eating humans), it is necessary to refrain from unnecessarily carrying honey around in open containers out of doors. If you leave it in a bowl or pour it on the ground as an offering, it is possible that it will disperse spores from bees who may have been either already sick or in a subclinical state of infection, and healthy insects could carry it back to their own colonies.

When consuming honey outside exercise caution: keep it in jars, and if you’ve spread it on something consume it right away before your six-legged friends get a chance to stick their proboscises in.

Like this: Slurrrrrp!

Finally, check your household for poisons against ants and other crawling insects, and safely dispose of them. Besides pesticides, some herbicides and fungicides can also harm bees. Use eco-friendly alternatives to control insects in your home and garden. Buy organic foods when you can, because organic agriculture is much friendlier to bees and other pollinators than the chemical-intensive alternative. And keep signing those petitions, marching against Monsanto, and educating the public about the importance of pollinators.

Frontispiece illustration for The Honey-Bee, by Edward Bevin (1827). Project Gutenberg.

What gardeners and stewards of land can do:

Are you re-wilding, restoring or caring for land? First of all, even though the situation with bees is not at all good, don’t panic or despair. That stupid meme that keeps circulating on social networks that claims Albert Einstein prophesied that without bees man has only four years left to live is, to put it politely, a stinking crock of lacto-fermented horse shit. First, because there is no evidence that he ever said such a thing. Second, the bulk of what people eat comes from wind-pollinated crops; and third, because unless there were other conditions driving a total environmental collapse, native pollinators would most likely take over from the honeybees and Mother Nature would begin to rebalance things.

Life on Earth will not end: the real risk is that our current agricultural system is not prepared to lose the bees, and there would be some uncomfortable readjustments ahead. In this sense, the bees are keeping us.

So you’d like to do something to benefit bees and other pollinators on public land? In 2014, Barack Obama issued a memorandum on pollinators calling for increased civic participation, increasing and improving pollinator foraging, growing mixes of flowers for pollinators on various publicly-managed lands limiting mowing, and avoiding pesticide use in sensitive habitats. I have attached a link to the memorandum in the References section. But a document like that is only as good as its paper or pixels if it isn’t used, and that means putting it into your arsenal of arguments for why pollinator-friendly policies should be adopted.

See if you can network with, chat up, lobby, or send petitions to local “agents” (decision makers) in the key bureaux, as well as trying to implement them in your local community, for example in town or county parks.

Sometimes, people wonder whether honey bees could or should be replaced as pollinators or have any business whatever in native plantings in North America. There are those who have suggested that native pollinators will swoop in to save our current food system once honey bees die off. However, this may be a little far-fetched, given current arrangements. Rusty Burlew, the director of the Native Bee Conservancy and author of the Honey Bee Suite pages, writes: “perhaps one day native pollinators will shoulder the bulk of our pollination needs – but it won’t happen within our current system of agriculture. It can’t. Successful transition to native pollinators will require nothing short of a complete overhaul of our current farming system … But the Green Revolution changed how we farm and, before long, there weren’t enough native pollinators to do the job. The fields were too big, the habitat was too scarce, and pesticides were everywhere … Even the people who are currently studying native pollinators concede that without significant changes, native bees might supplement – but not supplant – honey bees …

Some experts estimate that a transition would require up to 30% of current farmland converted to bee habitat. Hedgerows, borders, and habitat strips would have to be interspersed with crops. This reserved land would need to remain untilled and be planted with large numbers of flowering plants so that something was always in bloom. Thing is, even with all those resources devoted to wild species, it still might not be enough. We would have to change pesticide practices, stop poisoning roadside weeds, and eliminate larger-than-life fields. We would have to become stewards –rather than pillagers – of the land.

That’s a tall order, and one that is not going to be carried out within the easily foreseeable future. By all means, plant some wind breaks and hedgerows and learn to sustainably harvest or cultivate native edible plants, but … until a sustainability revolution comes about, what steps can we take right now? And how can we help both European honey bees and native plant and animal species in the Americas?

First of all, plant trees! Especially those that bloom very early in the spring (sallow, hazel, witch hazel), or during the difficult midsummer period when the “honey flow” (significant source of blooming, nectariferous plants) is at its minimum. Full-sized, so-called “standard” fruit trees with their larger crowns also provide very rich pickings for honeybees, even if their fruit can be hard for us ground-apes to reach without a ladder. They make venerable landmarks when full grown, and also live longer than the more popular dwarf or semi-dwarf varieties. If you don’t have your own land to plant them in, see if you can organize civic initiatives to get more plantings into your local parks and public spaces, or perhaps along roadways. The trees will benefit far more than just bees, as of course they provide shade, secure the topsoil, hold onto water, and offer shelter to insectivorous birds and possibly bats.

Besides trees, you can establish other plantings that are attractive to honey bees and other pollinators. As with trees, is especially beneficial to focus on plants that bloom at the beginning, hot dry middle, and end of the season, because these are the times when colonies are most at risk of starving. Ivy (Hedera helix) is quite a wonder: one English study determined that up to 89% of pollen pellets gathered by worker bees in September and October was taken from ivy, and even more nectar was being harvested, as 80% of bees were sipping rather than stuffing their pockets (see Garbuzov and Ratnieks). Unfortunately, though, ivy is very aggressively invasive in the United States, so it may be better to leave that landscaping tip for the Brits and Europeans. Wherever you live, be sure to include many aromatic, non-poisonous and nonhallucinogenic herbs in the garden so your honey will be safe and tasty. Bees like plants in the Asteraceae and Lamiaceae families, and both provide them with nourishment. With a little research and a little trial and error you will discover which plants are the most appealing to your bees and other pollinators. Sorry to say (because I love them), garden cultivars of roses are not such a good choice for your bee garden, as they have been bred to have more decorative petals than nectar and pollen-bearing parts, which are often hidden underneath. Entomologist Laurence Packer says the bees would like you to limit classic lawns, and skip wood chip or pebble mulch, which can be too difficult for native bees that want to burrow into the soil. Finally, don’t forget a source of water in your bee garden: if there aren’t any obvious places for them to drink (like a pond or rain puddles) you can set out a shallow basin with water filed with marbles or with straw or sticks floating in it so the bees have something to land on and will not drown.

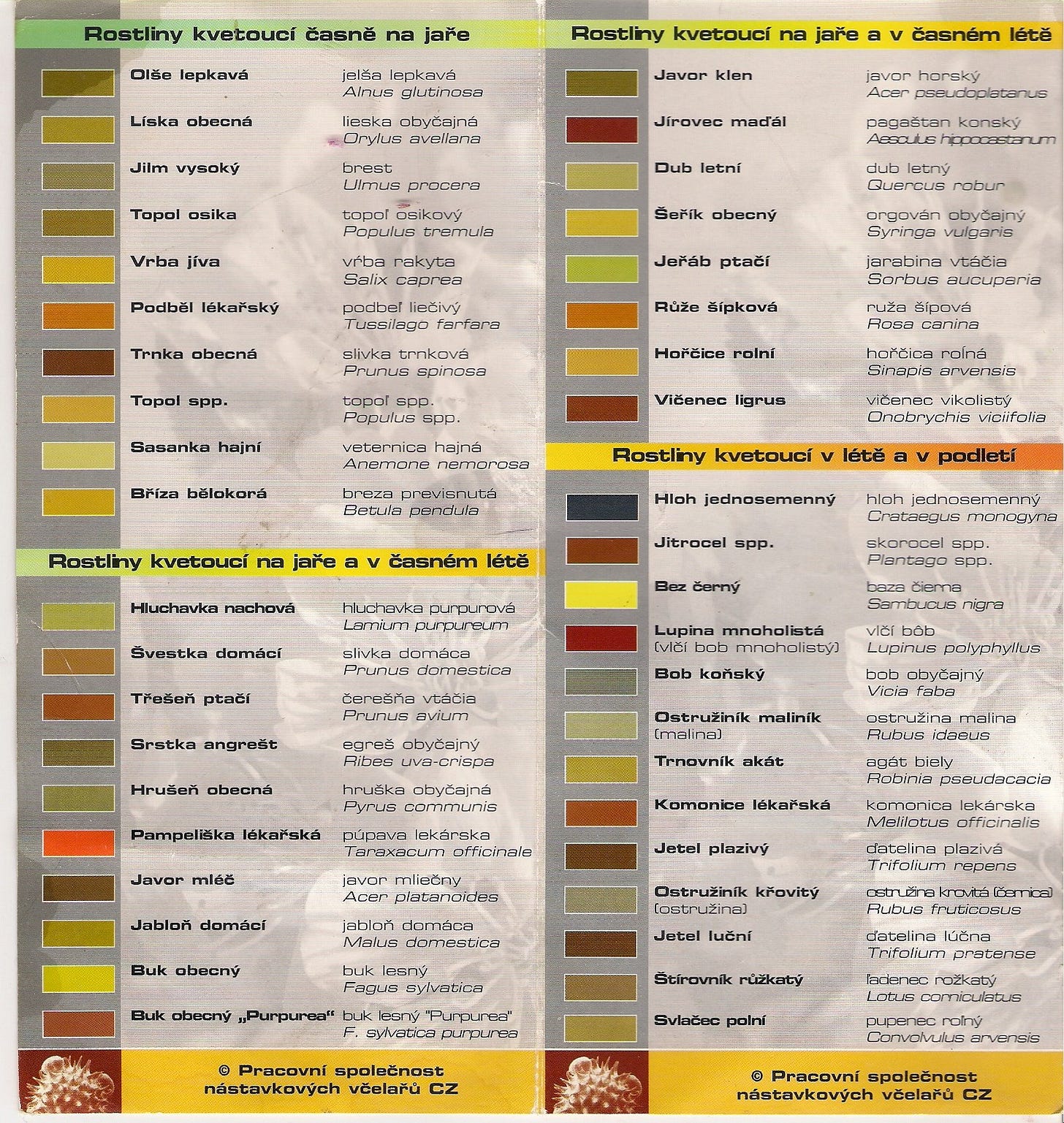

Once you’ve got your floral buffet and bee bar open for business, a fun activity is observing what color of pollen your bees bring home in their corbiculae or ”pollen baskets” and deposit into cells in their hive. If you look up “pollen color chart” online and find one appropriate for your geographical area and season, you will have a good idea of what plants they have been visiting and what is in bloom in your surroundings.

Above: a Czech chart made for beekeepers to identify local plant pollens by color.

By all means, think outside of the box-hives. Whether or not there is great habitat available nearby, you can still be a host to native bees by building them custom “bee hotels.” Instructions for this are available all over the internet: You won’t get any honey as a host to solitary wild bees, but you’ll have the opportunity to observe up close some important little critters that benefit many of your favorite plants. This makes a great project to do with kids, especially if you or they have good eyes and a camera.

You can even help scientists by sending your bee pics to the University of Florida’s “Native Buzz” citizen science project, which encourages participants to design and build nesting habitat for solitary bees and wasps, identify any that inhabit it, collect and record data, compare their insects with others around the U.S., and thereby contribute to knowledge about ecological webs of predators, prey, parasites, pollinators, etc.

These findings help build a growing database of information that helps scientists coordinate population data and ultimately lobby for better conditions for endangered insect species.

A little “ethnobeeology” outside of North America

This is not the place for an exhaustive list or in-depth treatment of the fascinating beekeeping practices that can be found in history, or still in the world today, so I will only glance over a few suggestions for your further study.

In Europe: if you live in a land in or to the north of the Alps where the native bees have been suppressed, replaced, or even exterminated, look up on sicamm.org whether there are any affiliated groups working to protect dark bees in your country. BIBBA is the place to go for dark bees in the United Kingdom. They will also ID bees – to determine whether they may be Dark European Honey Bees – if you send them samples: the contact address is right up on the home page at www.bibba.com.

Keep in mind what I wrote above: the defining characteristic of “dark honey bees” isn’t really their darkness, but a combination of morphometrics, genetic markers, and ecological and behavioral traits. If you want to try this, here’s what you do (sensitive-people alert: you will have to submit dead specimens for analysis.) Above all else, do not destroy a colony’s nesting place just to collect a few bees. That runs entirely counter to the purpose of investigating rare autochthonous species! BIBBA’s instructions are to put the “sample bees” you’ve captured in your freezer for 24 hours, then dry and pack them into a paper towel in a cardboard box (not plastic, so they don’t get moldy), and send them in by post to the address provided. If your bees’ morphometric measurements are close to the native bee they will conduct genetic testing to determine their type. They add that it would also be helpful if you also provide the history of where your bees originally came from, if you know.

Bees to not have to be recently frozen to be of value to researchers: archaeologists, history buffs, or browsers of estate sales should know that old collections of bee specimens, or samples obtained at archaeological digs are also valued by researchers, as they provide baselines for comparison with modern bees that have been exposed to foreign breeds over time.

Native bees of Central and South America

Mayan Melipona bees. Source: Mayan Melipona Bee Sanctuary Project.

You remember my brief discussion of how Christopher Columbus inaugurated Euro-American cultural contact with a raid on the natives’ apiaries? According to Brian J. Dykstra, “Indigenous people throughout the Americas developed extensive moral, spiritual, culinary, linguistic, taxonomic, technological, and ecological relationships with native bees – long before Columbus arrived” (Ethnobeeology on Facebook).11

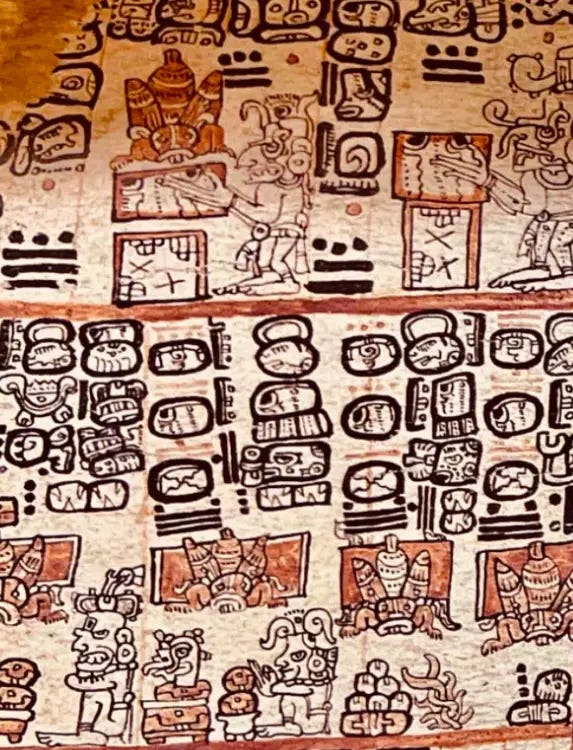

The Maya were keeping stingless Melipona beecheii bees in Yucatan and surrounding areas, which was illustrated in their Madrid or Tro-Cortesianus Codex. Maya beekeepers using horizontal logs with end enclosures of clay or stone, that housed the “royal ladies” (xunan kab) given to them by the god Ab Musen Cab.12

The honey produced by these bees is a bit more sour and runny than other types, and today it is a niche product sometimes sought after for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

The Madras Codex, illustrating Mayan melipona apiculture.

However, this tradition that has survived millennia is now under threat, and the Melipona beekeepers are dying out, or giving way to those who keep the more lucrative Africanized honeybees (Apis mellifera scutellata Lepeletier).

An additional blow to the art of meliponine beekeeping is that many of the meliponine beekeepers are now elderly, and their hives may not be cared for once they die. The hives are considered similar to an old family collection, to be parted out once the collector dies or to be buried in whole or part along with the beekeeper upon death … It is traditional in the Mayan lowlands that the hive or parts of the hive be buried along with the beekeeper to volar al cielo, “fly to heaven.”

Despite that these new hybrid bees are more aggressive, their hives are easier to manage than the native bees’ and they yield 100 kg or more honey annually. But, of course there are other drawbacks: “Africanized honeybees do not visit some flora, such as those in the tomato family, and several forest trees and shrubs, which rely on the native stingless bees for pollination. A decline in populations of native flora has already occurred in areas where stingless bees have been displaced by Africanized honey bees.” Source.

Native bees in Australia and the Pacific

Australia is home to stingless “Sugarbag” (Tetragonula carbonaria) bees. These girls actually provide honey, though not very much: per year, a colony only makes about 1 kg of tangy honey flavored with plant resins. “Bush honey” is something of a niche market specialty product, the kind that is praised on “slow food” blogs and it is only possible to produce in the warmer parts of the bees’ range. I’d really love to taste it, and if you have tried it I’d enjoy hearing what you thought about it in the comments below.

Sugarbag bee colony. MyModernMet.

Because Sugarbag bees produce only a tiny fraction of what European honey bees can, their honey will never compete with European honey bees to satisfy Australians’ sweet tooth. As specialists in orchids, they also do not pollinate the European crops that European-descended inhabitants of Australia like to eat, so they aren’t promoted by agribusiness either.

Some entomologists are looking into the domestication of other Australian native bees such as the blue banded bees as greenhouse pollinators, which is a very practical project, because honey bees will not do that job anywhere. (In Europe, there is growing demand for bumblebee keepers, whose girls pollinate all those veggies that are grown in the industrial-scale greenhouses of Holland and Spain). As you can read on the Amazing Bees blog, “There is a role in Australia’s future for the use of both European honey bees and native bees. They have different strengths and weaknesses in crop pollination and Australia would benefit from having commercially available stocks of both European bees and native bees.” It is possible that other species of native bees (not the Sugarbags) may be able to help with pollination of certain crops such as mango, macadamia, and strawberry.

As a final comment on the bees of Australia, I will note that Karel told me the dark honey bees that were brought over there by early generations of European colonists are of purer stock than many of the remnant colonies found in parts of Europe where they were exterminated. There is therefore interest among European Dark Honey Bee enthusiasts in re-importing them to their homelands.

In the Philippine Islands, the ant-sized stingless bees of the Tetragonula species are called Kiwot, Kiyot, Lukot, Lukutan, or Libog in local languages, and they are the most important remaining species to pollinate crops.

Likewise, in Africa and Madagascar, stingless Melipona bees have been traditionally kept, and their honey is valued as a medicine. Meliponiculture has the potential to provide good income to poor rural families while at the same time supporting the stewardship of old growth forests, native species diversity. and the health of local ecosystems.13

Conclusion:

Whether or not we are beekeepers, we are all, truly “keeping” bees, as we create the conditions for them to thrive or decline. And, as long as we are attached to our traditional fruits and crops, they are keeping us.

Even if we never buy honey, we still support beekeepers when we buy the fruits, nuts, and vegetables they pollinate for us. Many herbalists, natural healers and producers of high quality homemade cosmetics rely upon products of the hive (honey, pollen, propolis, royal jelly, wax), so it bee-hooves us to pay back the debt by taking what action we can to help bees.

Any truly bioregional form of beekeeping requires both attention to the match between bees and their environment and passionate action to protect local sources of bee foraging: forests, fields, pastures, and in-bee-tween lands like hedgerows, windbreaks, and roadside areas. Most of the time, this means paying attention to the quality of human-influenced landscapes so bees will have access to their natural food and medicine. When we can ensure this for them, the bees will repay the favor by keeping us in good health.

Honeybee on a Linden bloom at 9:30 pm on the summer solstice a few years ago. My photo.

References and Useful Resources:

Aussie Bee Pages, the home of the Australian Native Bee Research Center.

Rusty Burlew. “Wild Pollinators Cannot Replace Honey Bees” on Honey Bee Suite. Available here.

Ethnobeeology page on Facebook: sign up immediately!

M. Garbuzov; and F. L. W. Ratnieks, “Ivy: An Underappreciated Key Resource to Flower Visiting Insects in Autumn” in Insect Conservation & Diversity. March, 2013.

Tammy Horn, Bees in America: How the Honey Bee Shaped a Nation. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

E. Barrie Kavasch, Native Harvests: American Indian Wild Foods and Recipes. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2005.

I. Khalifman, Bees: A Book on the Biology of the Bee-Colony and the Achievements of Bee-Science. Moscow: Foreign Language Publishing House, 1953.

Joseph K. Macharia; Suresh Kumar Raina; and Eliud M. Muli, “Stingless Beekeeping: An Incentive for Rain Forest Conservation in Kenya. In: African Insect Science for Food and Health. Available at Academia.edu.

“Native Buzz” – see University of Florida, below.

Barack Obama (June 20, 2014). “Creating a Federal Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators [Memorandum]. Washington, D.C.: White House. Available here.

Laurence Packer, Keeping the Bees: Why All Bees are at Risk and What We Can Do to Save Them. Toronto: HarperCollins, 2010.

Pesticide Action Network Europe “Save the Honey Bees.” Available here.

Pollination by Honey Bees in the Philippines web pages. Available here.

Richters’ Herbs. Richters’ InfoSheet D9001. “Herbal Beekeeping”. Available here.

Friedrich Ruttner; Eric Milner; and John E. Dews, The Dark European Honey Bee: Apis mellifera mellifera Linnaeus 1758. British Isles Bee Breeders Association, 1990.

Andrew Schneider, “Tests Show Most Store Honey Isn’t Honey” in Food Safety News. [Unfortunately, this link has expired and cannot be retrieved.]

SICAMM: Societas Internationalis pro Conservatione Apis Melliferae Melliferae [International Society for the Protection of the European Dark Bee].

Claus-Christian Szejnmann, “’A Sense of Heimat Opened Up During the War’” In Heimat, Region, and Empire: German Soldiers and Heimat Abroad: Spatial Identities under National Socialism. Eds. Claus-Christian W. Szejnmann and Maiken Umbach.) Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Paul Stamets, “How Mushrooms Can Save Our Bees & Our Food Supply”. Speech from 2014 Bioneers Annual Conference Available to watch here.

University of Florida: "Native Buzz” citizen science project.

Jan Vondrák, “Je to jasná genocida” [It’s Clearly a Genocide]. Moderní včelař [Modern Beekeeper]. Early Spring, 2012. pp. 10-11.

Bee Wilson, The Hive: The Story of the Honeybee and Us. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004.

This article is based upon one originally published in Plant Healer Magazine in 2015, under the title "Rewilding Bees: Steps Toward Bioregional Beekeeping." It has been adapted and updated. Kiva Rose and Jesse Wolf Hardin, who publish Plant Healer Magazine, also publish numerous books about plant medicine. I am eternally grateful to them for publishing my article years before I thought I’d be able to write anything people wanted to read.

The 2015 article was written before all the heartbreak of losing my colonies the first time, and also before it was no longer self-evident that Nazism and fascism had been horrible civilizational mistakes. Now, it seems like no matter how many times the point is brought forward it’s still not enough.

I assume my readers are well aware that Columbus was a gleeful perpetrator of atrocities that shocked his contemporaries. Instead of linking scholarly sources that restate all of this I’m sharing a presentation made by The Oatmeal in the form of graphic comics that is suitable for sharing with those who still don’t know about Columbus’ rampaging in the Caribbean.

From Pillaging the New World to Swastikas in the Old: Snapshots in the Social History of Bees. For further information, also see The History of the Voyages of Christopher Columbus by R. Crowder, C. Ware and T. Payne, 1772 and The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus by G.P. Putnam, 1868.

See Tammy Horn, pp. 5; 19.

Thomas Jefferson quoted by Horn, p. 41.

Many species of earthworms are also invasive. Like honeybees and dandelions, they were introduced deliberately by European colonizers. “These transplants are more likely to consume aboveground leaf litter than native earthworms, altering habitat quality in a way that can hurt native plants, amphibians, and insects.

In the northern broadleaf forests of the U.S. and Canada, alien earthworms’ impact on soil stresses trees such as sugar maples by altering the microhabitat of their soils. This, in turn, sets off a string of food web impacts that help invasive plants spread. Ironically, for a creature synonymous with improving soil, some alien earthworms may alter soil properties such as nutrients, pH, and texture, leading to poorer quality crops, among other impacts.” Read more here.

And no, Native Americans did not have a “Worm Moon” in March. This tired misconception is based in the observations of Captain Jonathan Carver, who had been visiting the Naudowessie (Dakota) and other Native peoples. His comments about the “Worm Moon” refer to a different creature: beetle larvae, which begin emerging from the thawing bark of trees and other places at this time.

And this only makes sense, because earthworms are an invasive species in North America and were not (yet) present in the territories Carver visited

See Horn, pp. 42; 45. What did Native American recipes utilizing honey taste like? If you’d like to find out, I recommend E. Barrie Kavasch’s Native Harvests for an introduction to traditional Native and fusion dishes.

Wilson, p. 109.

Szejnmann, p. 133.

See Schneider.

I’m updating this article to include an announcement of the recent discovery of 261 Mayan beekeeping artifacts in Mexico. Workers preparing a site for railway construction in the Yucatán found a site where archaeologists then uncovered three limestone lids, panuchos, that Mayan beekeepers used to seal up the hollow logs, jobón, which they used as hives, and an assortment of other tools that were part of the meliponary. (An “apiary” is a facility where Apis mellifera is kept, so, logically, a meliponary is where Melipone bees are kept.)

See Macharia, et. al.

This is excellent. Thank you for sharing with us.

An excellent piece, Melinda. I very much enjoyed your many layers of research and references with regards indigenous beekeeping practices, and your powerful counter arguments for the 'bees will save the world' narrative. I also kept bees for nearly 5 years in the UK. And yep, mine also got sick or poisoned and had to be cleaned out. There are few sights more heartbreaking than a hive full of dead bees with their tongues sticking out. It was gutting, and a long way from the 'romantic beekeeper' image social media had sold me. So a learning experience for all that. Anyway, cheers for the post x