Grammatical gender, animacy, and the kinship of living beings

And why this Long Islander will never stop saying "you guys"

Gender reform in English

In the English-speaking world, gender issues in our language are having a moment again. Gendered language reform has moved in three directions: the first is to eliminate indications of gender from job titles, so we no longer have policemen and policewomen, but police officers. Instead of waiters and waitresses, and stewards and stewardesses, we now have servers and flight attendants.1

I don’t think too many people miss the old terms, but it’s interesting that when both the male and female terms aren’t replaced, it’s usually the female term that disappears, such as “actress,” which is increasingly replaced by “actor.”2 Aviatrix. Poetess. Shepherdess: as the 20th century progressed, the feminizing suffixes -ess and -trix were increasingly perceived as condescending. If women did something differently than men: flying aircraft, writing poetry, herding sheep, either they were picturesque, or assumed to be less competent. When no word existed that specified women in these professions and someone still wanted to indicate that a woman was on the job, they were sometimes modified by “lady” — for example, “lady doctor” and “lady judge.” But — in my view — far worse than feminine job titles was the old habit of referring to married women using their husband’s first and last names (e.g. Mrs. John Thomas), which completely erased them as individuals and assimilated them to the persona and assets (chattel) of their spouse, but this usage seems to have disappeared without too much fuss, probably because women were increasingly endowed with real political and financial power.

The second trend has been pushing back against the generic use of “he/him” as a pronoun, and “man” as both the generic word for human beings and male human beings. Old English, like contemporary German, used mann for generic human beings, in the same way we use “person” or “one” today. This is different than ein Mann, which is a male human being, or sometimes a husband. While the Old English mann was grammatically masculine, it did not express the biological sex or gender of the person it referred to: wīf was added on to make wīfmann (woman-person), while a man was wermann or sometimes wǣpnedmann (from wǣpn, which meant “weapon” or “penis”). It was only after the Norman conquest that wer- was dropped and “man” began to refer only to male human beings, and wīf developed into “wife”.

Thanks to this semantic blurring, and — let’s face it — also sexism, at this point there began long centuries of usage in English where “man” was considered to refer to both male human beings and the human being as a type. It was only more recently that pushback resulted in increased use of gender-neutral terms, such as “one,” the singular “they” (which has been a feature of English since at least the Renaissance era), “human beings,” etc.

It would be tempting to claim that a universal masculine pronoun only reflects sexism and patriarchy, but there are languages (e.g. Mohawk, and - to some extent - Masai and Welsh, or Swedish) where the grammar defaults to feminine gender, or the feminine is considered inoffensive when applied to men, while the reverse is not true. There are also languages, such as Irish and Scottish Gaelic, where the marked/unmarked status is more ambiguous. But the key question is whether there correspondingly less bias against women in places where these languages have been spoken. In order to analyze this, you’d have to take a long view, as long as the life of the language, and decide upon criteria for bias, discrimination, and misogyny and try to apply them comparatively.

This brings us to the third and most recent trend in language reform: neologisms that use the letter ‘x’ — such as “womxn.” I find this one vexing for multiple reasons. While it was intended to be more inclusive for trans women and others who are atypical, many find that it functions as an auxiliary category that separates them from the regular category of “women.” It puts part of the word “woman” under erasure, but this canceling has not been extended back to “mxn” — and probably never will be. Because only the spelling used for women changing, “man” still remains the default gender; the ‘x’ represents deviation and dissent from the norm, even as it reproduces it. This then has the curious effect of reifying women’s identity as an oppressed class, which is probably not the best tactic when organizing for equality.3

There are also proposals to introduce pronouns and titles that erase gender (e.g. “xe/xir” and “Mx”), because he/she and Mr./Ms. still reference gender. These neologisms attempt the erasure of social gender, and they are an impoverishment of our language. Some feminists have suggested that medical and healthcare texts replacing references to “men” and “women” with expressions such as “menstruators” and “people with prostates” is a form of female erasure, but I would argue that it isn’t. While these usages seem odd at first, the fact is, human beings can have all kinds of body parts and functions that don’t match what some people think they are supposed to be calling themselves. And if this language helps someone get a prostate exam, or a pap smear because they feel more welcome in a healthcare facility, it’s good for them and for the rest of society.

Yet despite “people with prostates” (etc.), even “people” has been giving way to “folks” / “folx.” “People” already isn’t a gendered term,4 so “folks” doesn’t represent a semantic difference in this regard; thus, because this substitution doesn’t quite achieve enough virtue signaling, gender-inclusiveness is performed by putting an ‘x’ at the end of “folx.”

Depending on whom you ask, this usage goes back to the ‘70s or the ‘90s in LGBTQ+ circles, and it may even draw upon the legacy of Malcolm X. “Folx” was traditionally part of the language people in these communities used to refer to their own in-groups, and to other groups that they felt were kindred. The ‘x’ was a nod to people who are nonbinary, transgender, or genderqueer in other ways. However, taken outside of this context, the usage is contentious: some people in the communities where the usage originated are pleased to see it spread, but others are unhappy or angry about it, and many feel that busybody SJWs appropriated it as yet one more opportunity to show off.5

The recent proliferation of “folx” is almost certainly related to the rise of “Latinx” since the early 2000s. White/English-speaking activists introduced this neologism to “solve” the problem presented by nasty, gendered languages that use the terms Latino/Latina. However, “Latinx” is widely despised; it is banned in Spain and Argentina; and the term mainly proliferates in academic environments that exclude the very people it is meant to describe.6 Moreover, because the letter ‘x’ behaves differently in English than in other languages, “Latinx” is actually unpronounceable in Spanish! The imposition of this English word has justifiably been denounced as yet an other example of cultural imperialism and colonialism.

The villain/thug/terrorist in me honors the villain/thug/terrorist in you

In a recent conversation, a Czech friend asked me if it was no longer acceptable to address people, especially in a mixed-gender group, as "guys." The question was sincere: they wanted to avoid causing offense.

"It means men and boys, right? Isn't is silly if you say 'Hi guys' to a group that includes two men plus your daughter?"

As a Long Islander, I feel I should set the record straight on our preferred second-person plural. While there are other regional (US) forms of the you-plural pronoun (e.g. y'all, youse, yinz, yunz, yintz), "you guys" has been the most popular choice in many regions for a long time. Yet, it’s surprising that it ever caught on, spread, and persisted so strongly in the US. That is because ...

… "Guys" is a historical reference to a Catholic terrorist, Guy Fawkes.

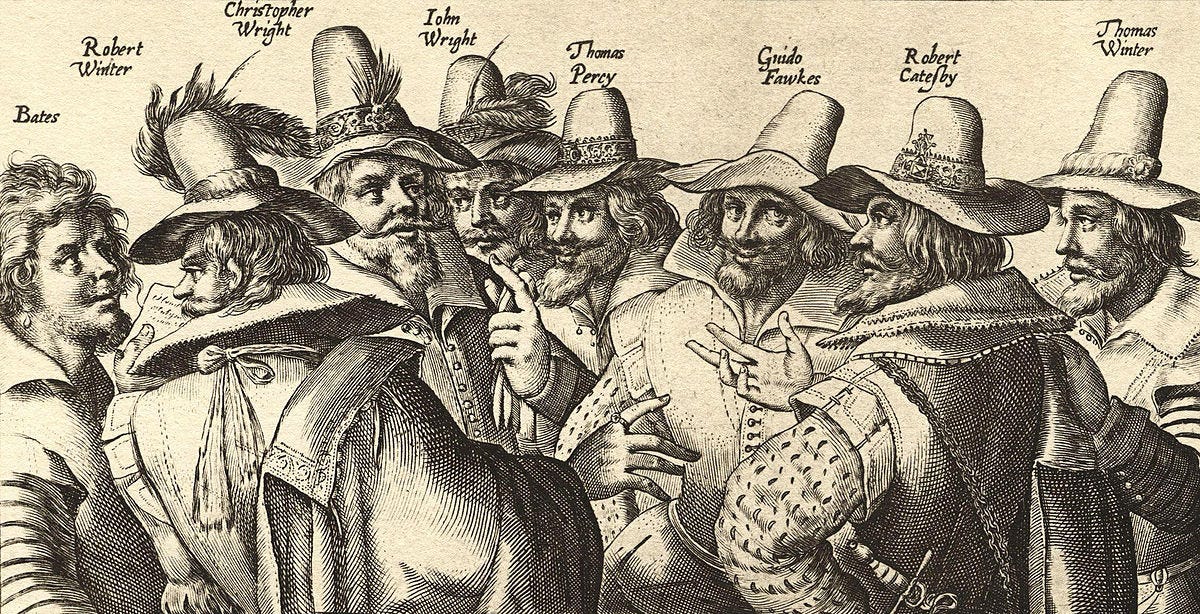

A copper engraving by Crispijn van de Passe dem Älteren after the Gunpowder Plot was revealed. Public domain image, Wikimedia. Eight of the 13 conspirators are depicted, and Guy (Guido) Fawkes is the third from the right.

He — Fawkes — was the Guy behind the Gunpowder Plot, a conspiracy hatched in 1605 to blow up 36 barrels of gunpowder under the House of Lords and incinerate the Lords, Commons, and Protestant churchmen in order to make way for a new Catholic government. However, the plan was foiled: Fawkes was apprehended by a search party in the basement before he had a chance to light the fuse.

He was interrogated, tortured, and executed, and the officials who had nearly been killed by the conspirators wanted to make sure everyone would "Remember Remember the Fifth of November, the Gunpowder Treason and Plot," so they declared a holiday for "publick thanksgiving" that the wicked plan had not succeeded.

In the celebrations, effigies of Guy Fawkes (and the Pope) were burned, and these dummies were referred to as "guys." By the early 18th century, the usage of "guys" started to spread to men, though mainly those who were low-class and seemed violent or depraved, perhaps as an equivalent to "villains" in the older usage of low-class, possibly dangerous thugs, or even potential terrorists.

In the next semantic shift, "guys" were no longer lumpenproles but working-class men, and then eventually "guys" were all men, and by the mid-20th century "guys" again expanded to include people of any gender.

When done mindfully, calling someone a "Guy" (Fawkes) is a recognition of their potential to take bold risks and make history. It's donning the Guy Fawkes mask used in V for Vendetta, and seeing the mask on the other person, as if to say (like a dark Namaste) "the terrorist/thug in me honors the terrorist/thug in you," while winking. The mask and the name are not an identity — they're a cloaky/daggery concealment! And, while I do not support Fawkes' intention to create a Catholic monarchy, I do have some appreciation for the idea — expressed in V for Vendetta — that governments should fear citizens more than vice versa.

Image of a protest in Bangkok, purchased by the author from Dreamstime. Image ID 43789059 © Mr. Namart Pieamsuwan | Dreamstime.com

The Guy Fawkes mask depicted in the graphic novel and film V for Vendetta has become a worldwide symbol of protest by “little people” against tyranny and oppression. As Alan Moore, author of V for Vendetta, told The Guardian, "I suppose when I was writing V for Vendetta, I would in my secret heart of hearts have thought: Wouldn't it be great if these ideas actually made an impact? So when you start to see that idle fantasy intrude on the regular world … It's peculiar. It feels like a character I created 30 years ago has somehow escaped the realm of fiction." (Source.)7

Interestingly, “guys” is also a fine example of the vocative in contemporary English, a language which otherwise doesn't use it that much. (Traditional vocative terms such as "lo" and "daddy-o" have disappeared, and "kiddo" has been repurposed as a cutesy nominative.) Saying "Guys" at the beginning of a sentence is more effective at drawing attention than “Folks/folx,” which needs at least a “Hey” in front of it. “Guys” comes a little closer to the emphatic "Hwæt!" at the beginning of Beowulf. And even if some scholars now say hwæt! was not exactly OE for "Yo, listen up!" it was still a clearly-marked introduction and a way to set the tone for the dramatic events that were going to unfold.

Logo of Hwaet Zine.

If you’re not a native speaker, it’s important to note that while “guys” works well as a plural address, it’s not very good in the singular: “Hey, guy, you dropped your wallet” sounds a little rude. However, this distinction between inappropriate singular/appropriate plural forms is actually a regular feature of English: “Ladies, I have something to tell you” sounds a lot better than “Lady … “ It would also be strange to address a child “kid,” though a roomful of children could be called to attention with “kids.”

Animacy: the original gender distinction

Many English speakers are unaware that grammatical male/female gender is a newer convention than animacy in the development of our language.

Let’s first release the idea that “gender” can refer only to male/female or masculine/feminine. The word “gender” comes to English from the Latin genus via French, and it simply meant “kind” until the 18th century. And by “kind” it meant grammatical category, and not biological sex or social performance of masculine and feminine roles. Simply put, the original meaning of gender was types or classes that become morpho-semantic categories, and the possibilities for distinguishing among them are practically unlimited.8 Feminists borrowed the word “gender” from linguists in order to speak about the classification of male and female human beings; not vice versa.

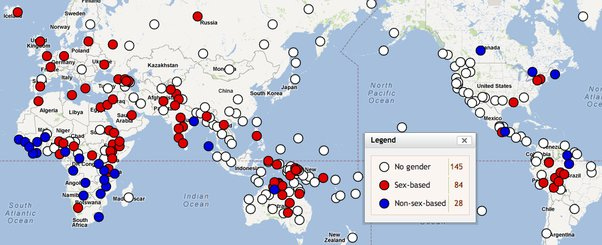

Map of languages where grammatical gender is sex-based, and non-sex-based by World Atlas of Language Structures.

Proto-Indo-European originally had two non-sex-based genders: animate and inanimate. PIE marked this feature with an -s, which became the nominative ending of many Indo-European languages such as Latin, which had -us; Greek, which had -os; Sanskrit’s -as, and Proto-Germanic’s -az. There are also nonrelated languages, such as Ojibwe, which make similar distinctions.

What’s animacy? Animacy indicates that something has vital life inside it either now, or that it did in the past. It is often reserved for people and animals, but there are other things, such as ghosts (which used to be alive and still have some for of vitality in them) that may behave according to the rules for this category. Sometimes, the distinction is human/animal rather than living/nonliving, or it could also be something that is considered socially “active” instead of passive.

When we describe a person, an animal, or even something else, such as a ship, as “he” or “she” or “they” rather than “it,” we are referring to them as animate. These pronouns are one of the last remnants of animacy in English.

In Czech, a (Slavic, Indo-European) language I speak every day, there are functionally four genders: masculine animate (e.g., men, dogs, ghosts), masculine inanimate (tables, bridges, attitudes), feminine, and neuter. You need to account for the genders of nouns, which determine which forms of adjectives and past-tense verbs must be used. (Thus, if I went for a walk, and so did my son, I šla and he šel, respectively). And then there are pronouns and demonstratives that must also conform to the gender of the person or thing they represent. Even the plural pronoun “they” indicates whether a group includes anyone in the masculine animate category. If there is one man and 100,000,000 women, the correct pronoun is oni. However, if the man leaves, they are ony. This is actually similar to the example of “guys” above: it would be odd to refer to 100,000,000 women as “guys,” but a mixed group is often called “guys” either directly (“hey, guys!”) or indirectly (“those guys love to party!”)

As if this wasn’t complicated enough, there is a kind of honorary animacy for certain masculine things that people like a lot. Bread, cheese, and joints (the rolled-up kind, not your knees and elbows) are included in this category.9 It’s quirky, but reflects a familiarity that reflects fondness and even, perhaps at a subconscious level, the sense that one’s life depends upon these staples. From what I have read, Ojibwe also has a kind of honorary animacy for special things, such as stones, which are sacred in their culture.

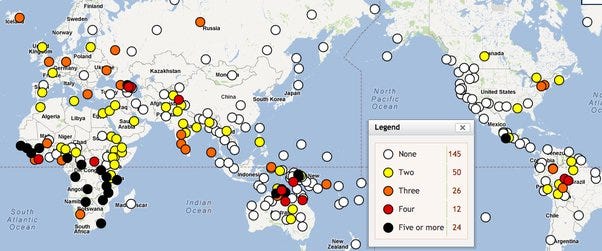

How many grammatical genders are typical in a language? The map below is far from complete, but it provides a quick overview:

Map of number of genders in selected languages by World Atlas of Language Structures. Mountain Arapesh, which is spoken in Papua New Guinea, has 13 genders, the Bantu language Ganda/Luganda has 14, and Ngan’gi in Northern Australia has 15. What is the maximum number? I don’t know: linguistic taxonomy sometimes creates subclasses instead of separate classes for the categories.

Is there any advantage to grammatical gender in languages?

Something like 38% of the world’s people speak a gendered language. For English-speakers, the question arises of whether there is some advantage to using grammatical gender. Clearly, languages can get by without it. But a greater degree of declension offers several advantages. One is it can have more flexible syntax. Thus, you can rearrange the order of words in a sentence (for poetic effect, or to change emphasis) and it still makes sense. You can do that a lot less of this rearranging in modern English than you could in Old English, Latin, or Polish. This is because if the pronouns, nouns, adjectives, and even verbs must agree with the gender of nouns, you will always figure out which pieces fit together.

Complex systems of declension are also easier to understand in environments with a lot of noise: thus if a loud sound drowns out a word, you will still figure out what was going on in the sentence because you know the color “red” was applied to something neuter, and “dangerous” was something feminine, etc. (See this discussion on Quora for these examples, and more.)

If we’re really going to reform language … ?

I take what I believe is a moderate view on the question of the reform of gendered language. On the one hand, I’m glad that we no longer have to suffer through idiocy like “Man, a mammal, breastfeeds his young,” which never would have happened if we had kept the Old English distinction of man/mann. On the other hand, “Xe”? No thank you! I will call you by your preferred name and pronouns, and I’d like you to call me by mine,10 but let’s not impose this on everyone.

I wouldn’t dare mess with Czech, as it’s a language I acquired as an adult, so while I have excellent proficiency, I am not a native here. Being a speaker of this language has colored how I view current efforts to scrub the last vestiges of gender out of English: the Puritanical zeal behind this drive gets my hackles up. While Czech society isn’t perfect — just like no other society is — I have never gotten the impression that it is more sexist than English-speaking societies, even though they speak such a gender-saturated language with female carrots and male celery, that I eat with my female fork sitting at the male table (etc.)

If I wanted to tinker with English I would think about building more animacy into it to compensate for what we have lost over time. As PIE evolved into the IE languages, the original animate class evolved into the masculine, and the inanimate became neuter, while collective neuter nouns were re-classified as “feminine.” (And, as far as I know, attempts to discover a patristic conspiracy behind this shift have come to naught.)

The dilemma in reintroducing animacy would be, is everything animate? Are only some things animate? And should there be a binary, or a continuum? There would be philosophical implications to each choice.

As I have mentioned above, Slavic languages come close to having a binary; however, the Diné rank nouns along a continuum from most animate (human) to least animate (abstractions).

According to linguists Robert Young and William Morgan,11 the scale looks like this: Adult human/lightning > infant/big animal > medium-sized animal > small animal > natural force > abstraction.

The botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer discusses her experiences as a speaker of Anishinaabemowin with Krista Tippett:

KT: So this notion of the earth’s animacy, of the animacy of the natural world and everything in it, including plants, is very pivotal to your thinking, and to the way you explore the natural world, even scientifically, and draw conclusions, also, about our relationship to the natural world. So I really want to delve into that some more. You said that there’s a grammar of animacy. Talk about that a little bit.

Kimmerer: Yes. This comes back to what I think of as the innocent or childlike way of knowing. Actually, that’s a terrible thing to call it. We say it’s an innocent way of knowing, and, in fact, it’s a very worldly and wise way of knowing. That kind of deep attention that we pay as children is something that I cherish, that I think we all can cherish and reclaim, because attention is that doorway to gratitude, the doorway to wonder, the doorway to reciprocity. And it worries me greatly that today’s children can recognize 100 corporate logos and fewer than ten plants. That means they’re not paying attention ...

... Kimmerer: Yeah. I can’t think of a single scientific study in the last few decades that has demonstrated that plants or animals are dumber than we think. It’s always the opposite, right? What we’re revealing is the fact that they have extraordinary capacities, which are so unlike our own, but we dismiss them because, well, if they don’t do it like animals do it, then they must not be doing anything, when, in fact, they’re sensing their environment, responding to their environment in incredibly sophisticated ways. The science which is showing that plants have capacity to learn, to have memory, we’re at the edge of a wonderful revolution in really understanding the sentience of other beings."

Here is an example of a beautiful application of this principle that honors both Anishinaabemowin and English:

Kimmerer: The plural pronoun that I think is perhaps even more powerful is not one that we need to be inspired by another language, because we already have it in English, and that is the word “kin.”

Tippett: That’s the plural of “ki”?

Kimmerer: Yes, “kin” is the plural of “ki,” so that when the geese fly overhead, we can say, Kin are flying south for the winter. Come back soon. So that every time we speak of the living world, we can embody our relatedness to them.

(Read the entire interview here.)

I think the question is how can it be grafted onto a language without becoming a resented imposition (like “womxn” or “xe”), or sounding kitchy, or — worse — like some kind of creepy cult that calls everyone “brother” and “sister” and wants to subordinate them to an ill-intentioned leader.

I have come to appreciate how some writers — particularly herbalists — have adopted the use of capital letters for animals, plants, and other nonhuman beings in the style of proper names. Something like “As I walked through the September woods at dusk, Evening Primrose released her fragrance and Wild Sow gnashed her teeth to warn me away from her little ones.” This doesn’t work as well in speech, because the capital letters aren’t evident, but saying Evening Primrose instead of “evening primroses” and “Wild Sow” instead of “a wild sow” does seem to shift the sentence into a more poetic register that opens new possibilities.

What do you think?

As an aside, you know whose titles are not being degendered? Kings, queens, and other aristocrats. And I don’t think it’s because this set is reflexively conservative: they have shown a willingness to change with the times in other areas, such as allowing daughters to inherit titles and changing rules that would ban spouses from different religions. Rather, there’s no point in seeking tiny advantages when you’re already at the top of a society.

Exceptions? Widow/widower still seems to be in use, with — unusually — the masculine form being the marked one. “Male nurse” is disappearing as more men enter this profession, and what I’m witnessing in Czech is that the term zdravotní sestra (literally, “health-care sister” — because professional healthcare workers were originally nuns) yielded zdravotní bratr (“health-care brother,” which is logical, but doesn’t derive from the religious history of the profession), but today it is more common to hear the male/female variations zdravotník/zdravotnice for health-care workers in general. Then, it can be further specified if they are a nurse, doctor, paramedic, or some other type.

“Womxn” is just a new iteration of an old theme of feminists wanting a word that doesn’t have “man” in it. I will be discussing folk etymologies at some length in an article that I’ll release soon after this one, so you’ll see this revisited, but from different angles.

In the 1900s, “wimmin” was suggested as an alternative spelling, and then “womon” (singular) and “womyn” (plural) were proposed as an alternative in the 1970s, but because that generation of feminists had particular (biological-determinist) conceptions of womanhood, it is now unpopular because it became with TERFs. And then there’s “wombyn” — ugh! Thank goodness that never caught on, though you never know — the kinds of people who want to control everyone’s uteri might eventually latch onto it.

I have read claims that the “problem” with the word people is that some racist or prejudiced speakers have used “you people” in derogatory ways to refer to groups they would like to say something more vicious about. This just goes to show that even the most neutral words, if delivered with poisonous intent, can cause pain.

Disclaimer: I support full rights for LGBTQ+ people, and I am not a TERF. If “folx” is preferred in some communities, that’s their business, and my comments are addressed to its adoption by people who are not LGBTQ+ and have just picked it up because it’s trendy. Do I hate all new words and trends? No, but I dislike smugness and shallow virtue signaling.

More discussion can be found in this article, which presents the results of a survey in which only 2% of registered voters of Latin American descent identified themselves as “Latinx.” The term is associated with Ivy League and Beltway elites.

More sources on Guy Fawkes as the origin of “you guys”: an article in WaPo, and another from Time.

A famous example is the Australian Dyirbal language, which has four gender classes, including a category for “women, fire and dangerous things” (which was the title of a book by the cognitive linguist George Lakoff):

Gender I: most animate objects, including all men

Gender II: women, fire, violence, exceptional animals

Gender III: edible fruit and vegetables

Gender IV: residual class

Thus, I would say bez mostu (without the bridge, with Czech bridges being masculine and non-animate) and bez Jana (without Jan, a man’s name). However, chléb (bread), sýr (cheese) and joint all behave like Jan, so you get bez chleba, bez sýra, and bez jointa.

Traditionally, animacy was not used as a category of gender by grammarians analyzing Czech, Slovak, Polish, Rusyn, and other related languages. It was considered a subcategory within the masculine gender. However, now it is more commonly acknowledged to be a category of equivalent standing.

Image source: Fun With Czech blog. If someone asked you to give human names to these animals, if you’re Czech, the snake might be Hugo, the zebra might be Tereza, the cat Maruška, the monkey Šárka, and the snail Šimon. Why? Because even though you know these animals can all be male or female, you’ll probably perceive them according to the grammatical gender used for their generic type. The speakers of German, French, and Spanish would name the animals differently.

My preferred pronoun is “she,” and my title is Dr. instead of Ms. because I hold a Ph.D. While “doctor” is not gendered in English, it is in Czech, and conventional usage here is paní doktorka: madame (female) doctor — a double reference to my gender. A man is called pan doktor.

Young, Robert W., & Morgan, William, Sr. (1987). The Navajo language: A grammar and colloquial dictionary (rev. ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press: 65–66).

Thank you! as a linguist and historian, I fully appreciate and deeply love this. I always remember that King Alfred's daughter, Aethelflaed, was recorded as being ' first man' (i.e.human being) to own a piece of virgin land. I particularly never want to be known as a 'womb-owner', or 'person with breasts', which seems like a cartoon description coined by aliens. Respectful address to plants, rocks and animals is wonderful, and I like 'kin.' Shakespearean English gives us 'coz' which I used to use with my actual cousin. Alas, since his death, I have no-one to employ this term with.

Thank you! Very interesting - I want to push forward tho' about finno-ugric languages and especially Finnish, from Finland. We have: "hän" = can be male or female, he/she; "se" = objects - and usually refers to animals also, trees, etc. There is discussion about this "se". We have -"tar/tär = adding to an ending makes it female identified; we have "-ini" ending for making something an endearment.... well, "he"= they; "sinä"= you singular; "te"= you plural; "me"= we...... There is a movement to increase the use of "hän" and "he" for all beings - trees, rocks, pets, cows, reindeer... and then get into reindeer husbandry and Saame languages one finds many new words.....