Glossolalia, glyphs, and the coefficient of weirdness: notes on magical languages (Part 1 of 2)

Everyday wishes and pious petitions

Magical speech is a category of utterances that attempts to create desired effects through the speaker’s will or the intermediation of supernatural forces or beings. We can further divide it into several types. The simplest is speech that is otherwise ordinary, but intended to achieve a magically empowered purpose. Everyone is familiar with examples like this:

Wishing on the first evening star this way is distinct from wishing on a falling star or blowing on a dandelion, because the incantation is a necessary condition for activating the wish potential.

Another very simple spell is the custom of saying “rabbit rabbit” on the first of the month to bring luck.

Petitioning prayers, such as the Prayer of Jabez in 1 Chronicles 4:10, also fall into the category of innocent wish magic, since they are spoken in ordinary language and they petitioning a socially acceptable supernatural power.

“Oh, that you would bless me and enlarge my territory! Let your hand be with me, and keep me from harm so that I will be free from pain.” And God granted his request.

Like most anthropologists, I would never draw a sharp line between religion and magic, but many cultures do work with distinctions of this kind, often operating along spectrums of benevolent/malefic, orthodox/heterodox, lay/clergy, folk magic/high magic, etc. Relevant distinguishing factors include the ordinariness or strangeness of the speech or other procedures used to participate in lines of cause and effect, how these operations participate in the broader culture, and what effects the magic workings have on the magician’s social position.

An outsider to American culture would certainly recognize recitations of “Star light, star bright” and Biblical prayers as magical speech, but they are hardly perceived as magical by Americans, because their culture considers attempts at working magic to be either primitive or diabolical, and devotion to God is thought to be virtuous or primitive, but not “magical.” The benign intent to bring blessings and luck to oneself or someone else defuses suspicions of malignancy and diabolism, and critics of superstitions generally can’t be bothered over something so harmless and low-stakes. (By contrast with, for example, fortune tellers who bilk clients out of large sums of money.)

Strangeness vs sympathy

There is an important difference that I want to bring up between magic purely or mostly based in words and workings that rely on elaborate settings or props: the former requires a certain degree of strangeness, while the latter imposes a similarity and “sympathy” between objects which allows manipulation of one to influence the other.

Figures of this type have been found worldwide, made from various materials ranging from stone, to wax, to bread, clay, textiles, etc. This Roman-Egyptian female figure bound and pierced with thirteen pins was found in a terracotta vase with a lead tablet inscribed with a binding spell. 4th century CE, held in the Louvre’s Department of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities. Source: Wikimedia. It is a perfect example of “sympathetic” magic that attempts to influence someone through an artificially-imposed similarity.

An Anthropological Perspective

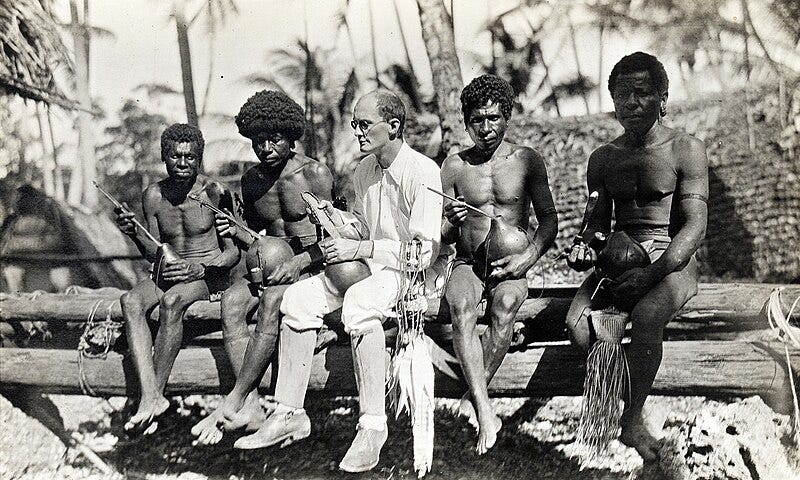

The Polish-British ethnographer Bronislaw Malinowski changed how many anthropologists and linguists approach language with his analyses of the magical practices of gardeners in the Trobriand Islands, 450-square-kilometer archipelago off the east coast of New Guinea.

As part of his functionalist approach to Trobriand culture, Malinowski illustrated how language is a tool, a document, and a cultural reality unto itself. His holistic theories made it clear that a story does not only represent symbols (which, themselves, stand for something else) nor does it merely explain something in a “just so” manner. Language and stories need to be understood as experiences of their own kind, and it is possible to discuss how language practices participate in their own fields of knowledge.

This field may contain a very narrow (purely individual), mid-range (limited to certain in-groups) or broader (society-wide) scope of play, depending on how secret or exclusive the ritual language is.

Malinowski with Trobriand Islanders, 1918. Wikimedia.

Yam magic

Yams are the nourishing staple crop of the Trobriand Islanders, and every family grows them. However, yams are much more than just food: they are also used as currency, so they signify wealth and power, and they are an integral part of all major life transitions: birth, marriage, divorce, and death. For some of these ceremonies, the yams must be exchanged — eating your own would be, well, weird. It is hard to imagine any food that has this level of ubiquity and significance in our culture, so we must sympathetically imagine how much importance Trobrianders attach to success in yam gardening.1

Yams mean everything, but they are tricky to grow, so a successful gardener requires good knowledge of soil composition, and must thin and stake the vines at the right times, and assess when they’re ripe for harvest. And in addition to these ordinary horticultural techniques, Trobriand gardeners also use magic [megwa], of both “white” (beneficent) and “black” (malefic) varieties, to ensure successful harvests, and they observe taboos, such as refraining from sex in or next to the gardens.

All Trobrianders, just like everyone reading this blog, know some basic-level magic spells (“I wish I may, I wish I might … “), and all of them do at least some of their own magic work. This tendency is accelerating: today, there is less reliance on experts in garden magic called towosi than there had been when Malinowski was recording spells.

A Trobriand gardener photographed by W. Schiefenhövel. Source.

However, two trends are currently working against what could have been a renaissance of individual magical practice. The first is that the Trobrianders are increasingly struggling to fill their richly-storied bwema (yam houses) for the last decade and a half.2 The second is that due to the increasing social power and prestige associated with Christianity, some Trobrianders, even some self-professed former witches [yoyowa], have recanted their prior beliefs and renounced the use of magic.3

The Coefficient of Weirdness

One of the factors that distances magical speech from ordinary speech is how weird (wyrd) it is. The sing-songy “I wish I may, I wish I might” is slightly stranger than saying something like “I wish I had an idea for a new blog article.” Malinowski used the wonderful phrase coefficient of weirdness to describe this distinguishing factor.

In order to use magical speech, one needs to be initiated into the lore or dogma of a magical belief system. While nearly everyone knows how to perform the star chant and the birthday song that precedes the celebrant blowing out their candles, many magical traditions and their associated languages are obscure to the uninitiated. An obvious example in the Western context is the Latin used in traditional Catholic masses.

In some cases, it is not the language itself but prosodic effects which distinguish magical speech from more ordinary utterances. Phonetic, rhythmic, and alliterative effects, unusual cadences and repetitions all signal that something special is happening both in the moment of utterance and — likely — afterwards.

Other speech acts used by magicians include counterfactuals and metaphor (“this rope is a snake,” “this wine is the blood of Christ”) and negations. There may also be “nonsensical” strings of phonemes, or “barbarous words” sprinkled into a recitation or text — I will discuss these below.

Sometimes, a magician’s language is untranslatable by others who are well-versed in it. The sound of their words creates a mood through only vaguely-perceived associations, or their speech may be a transmission from a god or spirit who declines to use ordinary speech. There may still be cues to who or what the speaker is channelling (e.g. bodily movements or gestures, other sounds) but at the far end of this spectrum, the non-semantic “nonsense” entirely takes over.

There isn’t an axiomatic connection between clarity/ordinariness of speech and beneficence (e.g., Latin-mass-reciting priests are thought to be sharing a blessing by Catholics), nor should obscurity be associated with evil intentions (e.g., Pentacostals who speak in tongues). However, the mastery of obscure languages or the granting of a “divine gift” of obscure speech does set the speaker apart from the rest of society, often in a way that enhances their status or, occasionally, evokes fear, as well as altering the speaker’s own consciousness.

Factors in the coefficient of weirdness

Glossolalia and Glyphs

“Speaking in tongues” (incomprehensible utterances) sometimes happens spontaneously, or it can be a cultivated skill. One of the first associations we have when we hear this phrase is with charismatic Christian sects who derive their practice from Biblical precedents. However, the practice of “speaking in tongues” is much older than Christianity. It was a feature of Dionysian and Orphic cults, and also featured in the Eleusinian Mysteries. Pythias and Sibyls, too, gave utterances in nonordinary language while they were in altered states of consciousness. Outside of the Southwest Asian and Western context, glossolalia is found in North American Indigenous conditions (e.g. the Peyote cult), in syncretic Voodoo religions and in the Gnawa trance possessions in Morocco, as well as shamanic practice worldwide.

Glossolalia does not communicate like other forms of speech; rather, it is pure expressive prosody. The “tongues” of those babbling in ecstasy lack consistent syntax or semantic meaning that can be understood by others, even others who are experiencing the same phenomenon at the same time. At most, a ritual leader or a diviner of some kind may interpret the message in connection with religious traditions or — in the case of oracles — with questions asked by those who came to consult with them.

Glossolalia is always considered a divine gift by practitioners, whether inspired by gods, spirits, angels, or other entities. The inspiration can be thought to come from realms “above,” or “below”: in the case of the Pythias, it was Python — the rotting corpse of a monstrous dragon in the nether realms underneath Apollo’s temple.

John Collier, Priestess of Delphi, 1891. Wikipedia.

Voces magicae, “barbarous names,” and charaktêres

Voces magicae ("magical names" or "magical words") or voces mysticae are pronounceable but incomprehensible magical formulas that occur in spells, evocations, charms, curses, and amulets in ancient Greece, Rome, and Egypt. They may also be called “barbarous words,” since they are not names or terms used in the magician’s own language.4

These words are sometimes alternative names of gods, spirits, or demons. Like the Hebrews, who were eternally interested in their god’s true name, the magicians using these names thought these were the true, authoritative, and semi-secret titles of the spirits they called upon. For example, the first spell in the Greek Magical Papyri, which is intended to summon a daimon assistant, includes the phrase "[This] is your authoritative name: ARBATH ARBAOTH BAKCHABRE" to remind everyone present how, including the daimon, how things work.

Often, “barbarous words” were borrowed from other languages, especially Egyptian, Greek, Persian, and Hebrew, but they were garbled and corrupted in their new (con)text. Many of the magicians who used these spells in the earlier Classical period may have been considered the words unintelligible to humans; however, sometime around 300 CE, Iamblichus argued that the words were of foreign (human) origin, but it was necessary to keep them in the spells, because they would lose their meaning when translated into Greek.

It is important to understand that when used in their “barbarous” form, these words or names are not mere survivals of older, poorly-understood ritual elements: their very strangeness indicates the mystery and prestige of languages believed to better channel certain prayers or invocations. In the words of Emmett Marks-Froot and Martin Devecka, they are “essential and agentive.”

The best magical effect can be achieved by giving the voicing of these names one’s fullest attention, allowing their strangeness to work its magic. These instructions tell magicians how they can attune to the full power of the barbarous names when performing the Bornless Ritual (Preliminary Invocation) of the Goetia.

When reciting the Ritual, each individual “Barbarous Word” should be “Vibrated” with a complete breath. That is:

1. Breathe in, imagining that one is “aspiring” to the Divine, and that one is pulling divine power or Light down through ones’ crown-centre;

2. Contemplate the Word at one’s heart-centre;

3. On the exhalation, chant or “vibrate” the word fairly loudly, so that you can both hear and feel it resonating — throughout your chest-cavity and body, throughout the room, and indeed throughout the universe.

Charaktêres are a mediating step between magical language and magical writing (the creation of magical literary texts and artifacts). These signs produce the effect of being letters, because they are letter-like, but they lack either semantic or phonetic correlations. The glyphs commonly include elements such as asterisks, and composite forms including lines, balls, points, and even simple hieroglyphs.

As glyphs, they not only stand for referents that are unknown to us, the uninitiated, but for magic itself, because they represent the fact of something inexpressible or incomprehensible to outsiders. Charaktêres can be either idiosyncratic to individual users or shared by small groups of initiates. Today, researchers generally do not know what they stood for.

Both charaktêres and voces magicae or barbarous names are used to amplify or enhance magical texts or artifacts; however, the purpose, procedure, and references that make up the rest of the spell or evocation are all described or reproduced in legible writing.

In her thesis (written in German), Kirsten Dzwiza analyzed 94 magical texts and recorded 699 different charaktêres occurring over 943 times. She found that charaktêres usually appear on apotropaic spells and phylacteries, but some examples were also discovered on ancient curse tablets. They may be loosely grouped in a recorded spell or on a gemstone, or accompany other words and images on a magical text or table. Often, like voces magicae, they are employed along with comprehensible arcane words; however, charaktêres did not represent complete alphabets or code languages. They were used sparingly, like a spice within the context of a spell that relied on the rest of its elements to provide meaning.5

An onyx intaglio in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art showing charaktêres alongside Greek letters. 2nd-3rd century CE. Wikimedia.

You’ve got that backwards: palindromes and backmasking

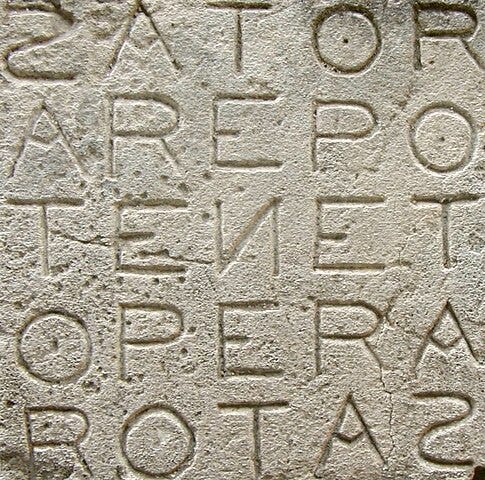

Many readers will already be acquainted with the enigmatic Sator square, which is a rebus, an acrostic, and a two-dimensional palindrome.

This example of the Sator square was etched onto a wall in the medieval fortress town of Oppède-le-Vieux, France. The letters ‘S’ and ‘N’ are reversed, which also makes it a partial ambigram. Wikimedia.

There were many other formulae of this type, some of which used foreign languages or voces magicae, as illustrated in the diagrams below.

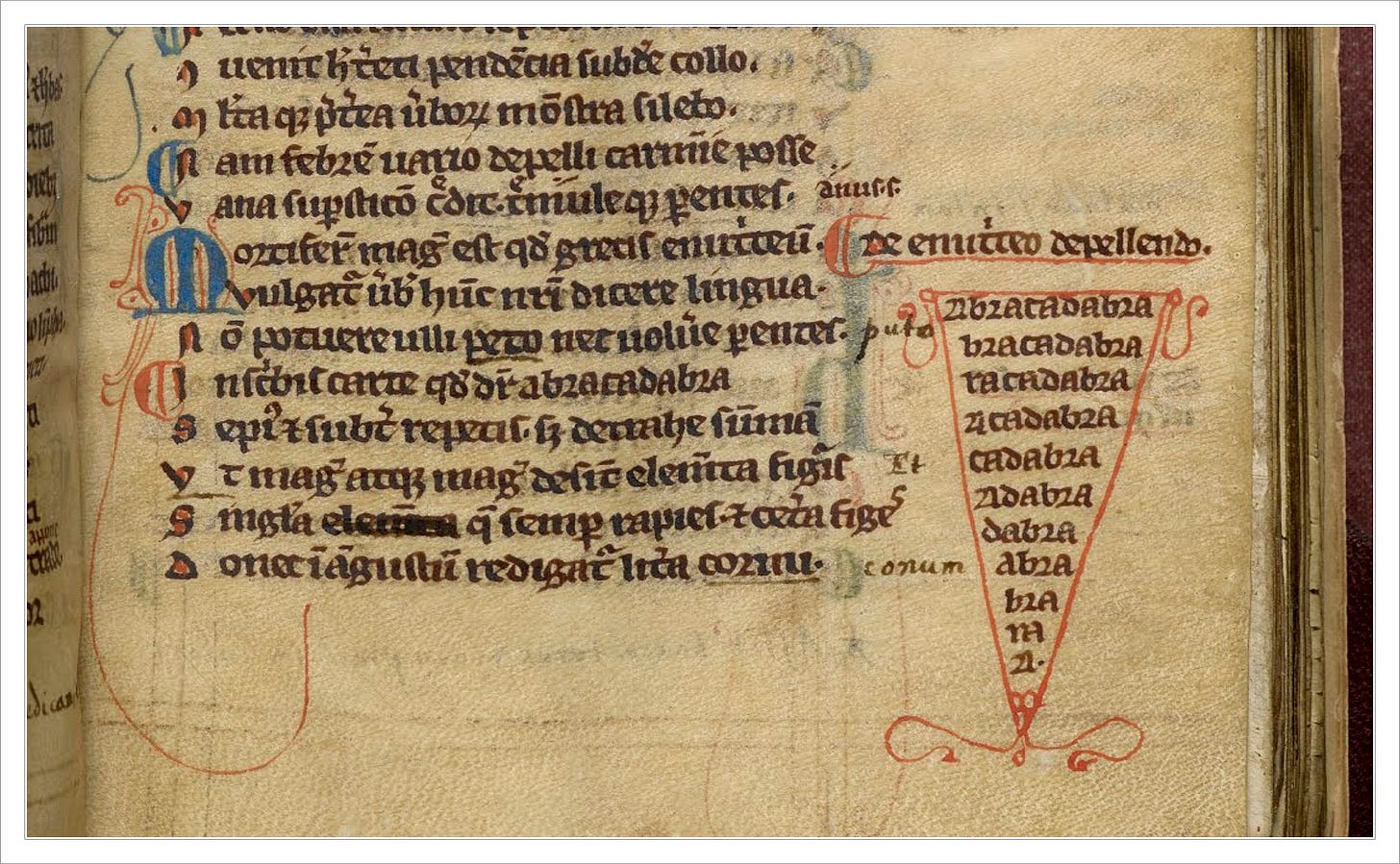

A 13th century version of the 2nd century medical text Liber Medicinalis by Serenus Sammonicus showing “abracadabra” written in triangular form. Source. Yes, the famous incantation used by stage magicians who pull things out of their hats has a long history in ritual and folk magic. Talismans intended to ward away or banish disease were made with this triangular inscription. Around the same time the tradition died out in folk magic, it was revived by Victorian esoteric orders.

An enigmatic Latin palindrome that has been called “The Devil's Verse” reads:

In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni.

Two possible translations are:

"Into the circle we go by night and are consumed by fire."

Or

"Gyrating by night, we are devoured by fire."

What could it mean? Witches at a Sabbath? Or burning at the stake? Or perhaps the more familiar scene depicted below:

Like a Moth to the Flame, by contemporary painter Tyran Schouten. I featured this enigmatic verse in my historical/occult novella Holy Fire: A Diabolical Pastorale, which is — at present — still unpublished, but may have a home with a publishing house in Chicago after I revise it some more. I’ll certainly let you know if/when a release is planned.

Creating witty or enigmatic palindromes has been a pastime of literati for millennia. It’s difficult to come up with good ones; however, anyone can render a familiar word or text strange and magical when they read it backwards. Do you remember how I mentioned at the beginning of the article that some people say “rabbit rabbit” before uttering any other word in the morning on the first day of every month to bring luck? Trying to attract good luck is easier than getting rid of bad luck. (That’s why, in Czech, the word for bad luck is smůla — sap — because it is sticky and hard to get rid of once it’s stuck to you.) So if you like to do the “rabbit rabbit” practice but you forget about it and say something else first when you wake up on the first day of the month, it’s possible to set things right again by doing something a little more difficult: saying tibbar, tibbar (that’s “rabbit rabbit” spelled backwards) last thing before going to sleep.

There is a traditional belief that reciting the Lord’s Prayer or another Christian text backwards will undo one’s baptism and/or invoke the devil. Occultists would do this in the context of pledging themself to a power that opposes the Church and its doctrines; i.e., the devil, either out of anticlerical sentiment or because they hoped to gain more personal power by throwing off the shackles of religious commitments. There is little doubt that this has been a real practice carried out by individuals and groups. For instance, when a certain Frater I.A. attempted this in his garden, the devil appeared to him, and “almost scared him out of his life.” Source. Whether or not one believes in the reality of the Christian god and devil, the act of backwards recitation of texts enshrined as part of the social and religious order has to be a powerful emancipatory experience.

Fear of the power of such backwards invocations was revived in the late 1970s, when Christian fundamentalists launched a minor moral panic with their claim that heavy metal and rock bands were putting backwards recordings of subliminal messages, usually of a Satanic nature, into their records. The technical term for this technique is “backmasking,” but the extent to which it has been actually practiced has certainly been exaggerated. The reason the panic faded probably had less to do with these individuals acquiring more sense, and more to do with the increasing prevalence of media such as CDs that could not be played backwards.6

Image credit: ID 34389404 © Elisanth | Dreamstime.com. Purchased by author.

Loose vowels: Old MacDonald, PGM rites, and Rudolf Steiner

Another form of magical speech that boosts Malinowski’s “coefficient of weirdness” is the use of long strings of vowels.

Above: initiating kids into the mysteries of foreign languages and strings of barbarous letters: EE-I-EE-I-O !!! I’m not kidding — it really is a legitimate introduction into some of the mysteries of using language, such as accepting that other speech communities exist (in this case, cows, pigs, dogs, etc.) and that we can communicate even when our utterances — the strings of vowels - don’t make “sense.”

We recognize a more formal example of magical praxis in the Mithras Liturgy, a complex syncretic rite that was probably compiled in the 4th century CE from earlier hermetic sources.7 One of the invocations is read thus:

EEO OEEO IOO OE EEO EEO OE EO

IOO OEEE OEE OOE IE EO OO OE IEO OE

OOE IEO OE IEEO EE IO OE IOE OEO EOE OEO

OIE OIE EO OI III EOE OYE EOOEE EO EIA AEA EEA

EEEE EEE EEE IEO EEO OEEEOE

EEO EYO OE EIO EO OE OE EE OOO YIOE

I don’t know what the ancient theory underlying the practice was, but in the 20th century, Rudolf Steiner elaborated at great length about the spiritual dimensions of consonants and vowels, amidst a lot of his other synthetic systematization of everything his mind could grasp into cosmic hierarchies.

Thus if a Man in the days of ancient civilization uttered the name of a God in vowels, a planetary mystery was expressed. The deed of a divine being within the planetary world was expressed in the name. Were a divine name expressed with a consonant in it, the deed of the divine being concerned reached in thought to the representative of the fixed star firmament—the Zodiac.8

Here is another essay where he explores this area:

And the vowel element—in this we have the soul which plays upon the instrument. The soul provides the vowel nature. Thus when you embody in speech the consonant and vowel elements, you have in every manifestation of speech or of song a self-expression of the human being. The soul of the human being plays in vowels upon the consonants of the musical instrument—the human body.

Now if, as I said, we are considering the speech that forms a part of present-day civilisation, we find that our soul, whenever it brings forth vowel sounds, makes use to a very great extent of the brain, the system of head and nerves. In earlier ages of human evolution, this was not the case to the same degree …

If we lift ourselves into the spiritual world, in the way I have described in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment, we first attain Imagination or Imaginative Cognition, as I have often told you. Now when we reach this point, we find that we have lost the consonants. We still possess the vowels, but the consonants—to begin with at any rate—are lost. In the Imaginative condition, we have in effect lost our physical body—i.e. we have lost the consonants. In the Imaginative world, the consonants no longer appeal to us. To describe what we have in that world adequately in spoken words, our words would have to consist, to begin with, of vowels only.

We have lost the instrument, and we enter a pure world of sound, where the vowels are indeed coloured and shaded in manifold variety, but all the consonants of earth are in effect dissolved away in the vowels.

Magical ciphers

While most so-called “constructed” languages (Esperanto, Klingon … )9 are created through the efforts of many people, many of what we call magical languages in the Western tradition are simply sets of substitution ciphers. These codes can easily be created by a single individual and anyone who is entrusted with the decoding formula, or who works it out themself, can read it. Magical cipher codes simply replace the letters used in a language with symbols, or sometimes they prescribe the replacement of the usual letters with others from the same alphabet according to a formula (e.g. the Caesar Cipher).

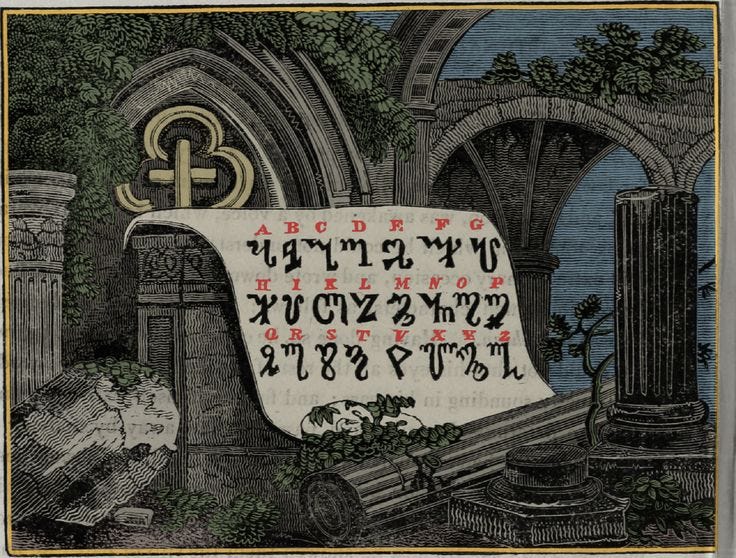

The Theban Alphabet was introduced in 1518 in Johannes Trithemius’ Polygraphia. He alleged its earlier origin in the Sworn Book of Honorius (thus titled because of its attribution to an ancient magician from Thebes). This set of letters is popular in Wicca and other witchcraft traditions, so it is often called the “Witches’ Alphabet.” And Cornelius Agrippus brought forward several occult alphabets in his Three Books of Occult Philosophy: the Celestial Alphabet, Transitus Fluvii (Passing of the River), and Malachim. Source.

Another magical language called Enochian was created by the Renaissance occultist John Dee, who claimed it was taught to him by angels.

John Dee and Edward Kelley Evoking a Spirit, by Ebenezer Sibley in The Astrologer of the Nineteenth Century ca 1825. Wikimedia.

Dee and his colleague Edward Kelley presented Enochian as the language that God used to “give an objective form to his mind” (i.e., to create the universe). It is the language of the angels, and was used by Adam when naming the animals. In fact, all of humanity spoke this tongue until the fall of the Tower of Babel and the ensuing polyglottal. Over time, he said, it degraded, but Semitic languages, such as Hebrew, are debased forms of the original angelic or “Adamic” language.

Magicians who want to communicate with angels should learn Enochian, which Dee also calls “Holy Language,” “Celestial Speech,” and “First Language of God-Christ.”

The name “Enochian” was conceived in service to Dee and Kelley’s assertion that the Biblical patriarch Enoch had been the last human (before them) to know this language.

Besides the legitimizing story based in Biblical lore, Dee also likened his creation to a “Language of the birds” — which I will discuss in the second part of this article.

John Dee’s manuscript diary for 6 May 1583, showing the 21 letters of the Enochian script. Wikipedia.

One problem with these cipher codes is they are fairly simply to crack by observing repeated words and repetitions and then filling in the rest of the blanks like contestants do on game shows like Wheel of Fortune. It’s easy to construct and use cheat sheets. “Secret decoder rings” were popular toys and gimmicks offered to children in cereal boxes or via mail order in the mid-20th century, which surely caused a devaluation in the prestige of these forms of writing.

This cypher wheel, which is sold on Etsy, will help you decode Celtic Runes, Theban, 2 rows of modern Latin, Ogham, Enochian, and upper and lower case Greek letters.

One of the justifications for secret codes is the real risk of owning and using forbidden texts in a repressive culture. Secular and religious authorities of various kinds have sought to extirpate heresy and other unwelcome ideas, or works by people whose ideas they rejected. Leaving aside the Third Reich and communist regimes, the book burning tradition in the Western world is mostly descended from a Christian tradition established by Constantine. After the First Council of Nicea in 325, he issued an edict against the Arian heretics which prescribed the destruction of their books by fire. Failure to comply would incur capital punishment. Later that century, Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria ordered Egyptian monks to destroy all heterodox works. The ones that remained comprise what is now known as the “New Testament.”10

Literacy only became widespread in industrialized countries in the 19th and 20th centuries. In eras when the skills of reading and writing were a rare preserve of elite classes, the common folk regarded literary skills as potent with menace (hence the common Early Modern tropes of the dangerous book of magic and of the devil requiring signatures in a book or a contract). Even the learned classes had a strong respect for the power of books to disseminate dangerous ideas. The grimoires of accused sorcerers were often burned along with them because they were thought to host and emanate malefic powers. I wish this were a chapter we could leave in the past, but unfortunately, banning and even burning books is still all too widespread. In the example below, an elected official is showing his contempt and violent hatred toward all ideas (lumped together as “woke”) that he would like to destroy.

State Senator Bill Eigel torching a pile of cardboard boxes as a “metaphor for how he would attack the ‘woke liberal agenda.’” This took place in 2023 at a “Freedom Fest” event in Defiance, Mo. "From a dramatic sense, if the only thing in between the children in the state of Missouri and vulgar pornographic material like that getting in their hands is me burning, bulldozing or launching (books) into outer space, I'm going to do that," Eigel said in an interview with The Associated Press. Source.

Reciprocity

If we look back to Malinowski’s insight that language is a tool, a document, and a cultural reality unto itself, we see a reciprocal influence between the magician and the world: magical language enchants the magician’s mind and perception, and the magician spreads this influence further afield in a process that is real in the same way as any other social fact.11

Also: special symbols and letters look magickal as fuck, and reading a thoughtfully enhanced document certainly enhances a magician’s experience. This has likely been a higher priority than actually keeping the letters and texts “secret.”

It would be banal to say that speakers, including magical speakers are constantly shaping and reinforcing their languages. But when nonordinary perceptions are shared and reaffirmed, and when wishes come true and prayers feel heard, it builds trust in the myths and metaphysics underlying magical practice. As I will discuss in Part 2 of this article, this has created a long lineage of heretics, poets, and healers that shimmers between the borders of what is real and imagined, and opens gateways into wonder … and bullshit.

John Griswold, Alchemical Allegory, 2022.

Part II of this article — Folk etymologies, bullshit, the doctrine of signatures, and the "Language of the Birds" — will be posted within the next day or two.

Michelle MacCarthy explains: “Nearly every family has a separate kaymata garden exclusively for yams, grown for someone else in the community, often a sister, mother, or village headman. No matter who receives them, the tubers, MacCarthy says, touch everyone from a bride-to-be to the Paramount Chief. They inspire annual celebrations, enable proper grieving, and even structure the calendar year, which aligns with the yam-harvesting cycle. The Kilivila word for ‘year’ is teytu—also the word for the esteemed Dioscorea esculenta, or lesser yam.”

The dissipation of magic, whether it’s caused by Christianity, climate change, or capitalism, is part of a cultural unraveling process. As yam yields decrease, Trobrianders are increasingly forced to buy food from stores using cash earned by their relatives who earn wages for their labor in cities. Their reliance on exchange networks that link extended families, and people from outside their villages has weakened, and nuclear families are gaining importance. The new, narrower exchange networks further diminish the importance of yams.

But yams are still desired. While the extent to which black magic is employed to acquire them is unknown, another covert art is becoming widespread: theft. While this was once the most serious kind of taboo, it’s now a daily nuisance. Yams used to be left stacked in public displays, but hungry people see unguarded food and take their chance of incurring the disgrace of being caught in what was once the most shameful category of crime.

Read more on Atlas Obscura.

Read more in the article cited above: “The Elaborate Yam Houses of the Trobriand Islands”.

Pink Floyd had a sense of humor, and put a very diabolical message into their song Empty Spaces: “Congratulations. You have just discovered the secret message. Please send your answer to Old Pink, care of the Funny Farm, Chalfont… Roger! Carolyne’s on the phone!”

Here, you can also read more examples of what people thought had been backmasked into popular songs.

Certainly, part of the anxiety about backmasking was related to the public’s hazy understanding that subliminal forms of influence could be employed by corporations and politicians to influence consumer behavior and political perceptions. We still see instances of book burning, and updated “satanic panic” trends track themes of malicious biomedical engineering (the adenochrome conspiracy theory), or they are attached to entire powerful classes of people (Hollywood, political insiders).

Personally, having been exposed to a bit too much anthroposophy when my children were attending Waldorf schools, I can acknowledge a few nuggets of greatness in Steiner’s thought, but altogether I find it unwieldy, and, as many others have noted, deeply racist, because it was influenced by ideas prevalent in his time. However, the international Waldorf schools and Anthroposophy movements have yet to fully reckon with the legacy of Steiner’s racist thinking, because to do so would have marked him as a man of his time and not as a transcendent prophet. The other legacy of his milieu and his personality is the top-heavy grafting of Christian supremacism grafted onto Helena Blavatsky’s Theosophy. In my view, the schooling with ascended teachers that Anthroposophy promises after we die is nothing more (or less) than culturally-specific hierarchies of spirit over matter based in particular Southwest Asian religious traditions. While these traditions excite many who would like to merge with “light” or with spiritual beings inhabiting purely spiritual realms after they die, this prospect leaves me cold. If I could take the animist equivalent of a Boddhisatva vow, and pledge whatever of my mind, vitality, or daemon is left over after death to defend and renew a wooded glad or a stream, I’d do that until forever, and never seek any “heavenly” afterlife.

Nor do I revile the forces that Steiner characterizes as “Ahrimanic.” Ahriman is an exotic name he borrowed from Zoroastrianism. Steiner considers Ahriman a destructive spirit who took over the role of deceiving mankind from Lucifer. Both of these beings are separate from, hierarchically lower, and inimical to God and to the true needs of the human soul. For Steiner and his followers, Ahriman is the active principle in science, objective ways of thinking, genetics, and materialism (in the strictly negative sense of the word), and his influence hardens the human soul. Steiner’s systems of philosophy and education — Anthroposophy and Waldorf schools — are intended to counter this influence because (he believes) Ahriman is going to incarnate in physical form in order to mess with Christians in the third millennium. You can read about it in Steiner’s speech “The Ahrimanic Deception,” which is available here.

Here’s a categorized list of constructed languages.

Source: Elaine Pagels: Beyond Belief.

The concept of “social facts” is elaborated by Emile Durkheim in The Rules of Sociological Method [1895]. In short, social facts consist of social norms, values, structures, and shared beliefs and feelings that transcend the individual and can exercise social control. Some of the areas where we feel these norms are in institutions like kinship and marriage, the language we speak, the use of currency, religions, political organization. Deviating from expected patterns of behavior can bring consequences ranging from disapproving side-eye to shunning to the death penalty.

To give a simple example of how it works, I may not feel reverence for something that others who are holding a “moment of silence” feel, and I may not believe what they believe, but if I deliberately breach the norm of remaining silent with the other there will probably be strong repercussions. Moreover, during the moment of silence I will feel a strong (yet poorly definable) pressure to conform with what the others are doing.

Great essay!

📖Here’s a poem inspired by translating the Latin version of The Devil’s Verse through dozens of languages and back to English, then reassembled for deeper meaning.

In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni

"Sleep well, October consumes the warmth with night.

Moistened, extinguished, memories lost again.

I'm deep in cycles, tired in the middle of nowhere.

We go for a walk, circling the same way we came around.

I'm off sleep, surrounded by hours of my death walking.

I remember, ignite, I am bright.

We are burning.

Shine mine knowing sight.

Wandering in dream, time took me to a central well.

Leaving me wondering, my quest to fill a grail?

In the middle of morning, I wake up.

In my heart, I swear together we are going dark.

In my opinion, around sleep his thoughts meet mine.

I have no idea, I have wander.

We go for a walk at night, and are consumed by fire.

I am neither side, a ghost adrift in bright, gyrating gardens."